Shang Dynasty

- The content on this page originated on Wikipedia and is yet to be significantly improved. Contributors are invited to replace and add material to make this an original article.

The Shang Dynasty (Chinese: 商朝) or Yin Dynasty (殷代) (ca. 1600 BC - ca. 1046 BC) is the second historic Chinese dynasty and ruled in the northeastern region of the area known as "China proper", in the Yellow River valley. The Shāng Dynasty followed the quasi-legendary Xià Dynasty and preceded the Zhōu Dynasty. Information about the Shang Dynasty comes from historical records of the later Zhou Dynasty, the Han Dynasty Shiji by Sima Qian and from Shang inscriptions on bronze artifacts and oracle bones—turtle shells, cattle scapula or other bones on which were written the first significant corpus of recorded Chinese characters. The oracle bone inscriptions, which date to the latter half of the dynasty, typically recorded the date in the Sexagenary cycle of the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches, followed by the name of the diviner and the topic being divined about. An interpretation of the answer (prognostication) and whether the divination later proved correct were sometimes also added.

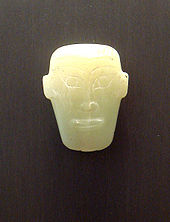

These divinations can be gleaned for information on the politics, economy, culture, religion, geography, astronomy, calendar, art and medicine of the period, and as such provide critical insight into the early stages of the Chinese civilization. One site of the Shang capitals, later historically called the Ruins of Yin (殷墟), is near modern day Anyang (安陽). Archaeological work there uncovered 11 major Yin royal tombs and the foundations of palace and ritual sites, containing weapons of war and human as well as animal sacrifices. Tens of thousands of bronze, jade, stone, bone and ceramic artifacts have been obtained; the workmanship on the bronzes attests to a high level of civilization. In terms of inscribed oracle bones alone, more than 20,000 were discovered in the initial scientific excavations in the 1920s to 1930s, and many more have since been found.

Archeological discovery

During the Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD), scholar-bureaucrats and the Chinese gentry became avid antiquarians and collectors of ancient artwork, some claiming to have found Shang Dynasty era bronze vessels with written inscriptions.[1] Despite this, archeologists of the 19th century knew only of written records and historical documentations spanning as far back as the Zhou Dynasty (1046 BC–256 BC), but no earlier.[1] In 1899, it was found that Chinese pharmacists in late Qing Dynasty China were selling "dragon bones" marked with curious and archaic characters.[1] By 1928, these "dragon bones" were finally traced back to their origin at a site near Anyang in the Yellow River valley, modern Henan province, where the National Government's Academia Sinica began an archeological excavation.[1] Work at the site was halted during the Japanese invasion beginning in 1937, but by 1950 another Shang capital had been discovered near Zhengzhou.[1]

At the excavated royal palace of Yinxu, there were large stone pillar bases found along with rammed earth foundations and platforms "as hard as cement," which originally supported 53 buildings of wooden post-and-beam construction.[1] In close proximity to the main palatial complex, there were subterranean pits used for storage, service quarters, and housing quarters.[1] The remnants of the rammed earth walls at Zhengzhou are determined to have risen 27 feet in height, and formed a roughly rectangular wall 4 miles around the ancient city.[2] Construction of these rammed earth walls was actually an inherited tradition by the Shang civilization, since much older rammed earth fortifications were found at Chinese Neolithic sites of the Longshan culture (c. 3000 BC–2000 BC).[2] In 1959, the site of the Erlitou culture was found in Yanshi, south of the Yellow River near Luoyang; their culture is often associated with the legendary Xia Dynasty that preceded the Shang.[3] They also had large palaces that also suggested the existence of a dynastic kingdom preceding the Shang.[3] Radiocarbon dating suggests that the Erlitou culture flourished ca. 2100 BC to 1800 BC.[4]

Cowry shells obtained from the seacoast were also excavated from Anyang, evidence that suggests the Shang were somewhat of a maritime people.[4] Neolithic sites one hundred miles off of mainland China's southern coasts of Fujian — on the island of Taiwan — are dated as far back as 4000 BC.[4] However, there was very limited sea trade in ancient China, since China was isolated from other large civilizations during the Shang period.[4] Trade relations and diplomatic ties via the Silk Road and Chinese maritime ventures to the Indian Ocean to reach other formidable empires did not exist until the reign of Emperor Wu during the Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD).[5][6]

History

The Shang dynasty is believed to have been founded by a rebel leader who overthrew the last Xia ruler. Its civilization was based on agriculture, augmented by hunting and animal husbandry. The Records of the Grand Historian states that the Shang dynasty moved its capital six times. The final and most important move to Yin in 1350 BC led to the golden age of the dynasty. The term Yin dynasty has been synonymous with the Shang dynasty in history, and indeed was the more popular term, although it is now often used specifically in reference to the latter half of the Shang Dynasty. The Japanese and Korean still refer to the Shang dynasty exclusively as the Yin (In) dynasty.

A line of hereditary Shang kings ruled over much of northern China, and Shang troops fought frequent wars with neighboring settlements and nomadic herdsmen from the inner Asian steppes. The capitals, particularly that in Yin, were centers of glittering court life. Court rituals to propitiate spirits developed. In addition to his secular position, the king was the head of the ancestor- and spirit-worship cult. The king often performed oracle bone divinations himself, especially near the end of the dynasty. Evidence from the royal tombs indicates that royal personages were buried with articles of value, presumably for use in the afterlife. Perhaps for the same reason, hundreds of commoners, who may have been slaves, were buried alive with the royal corpse.

The Shang dynasty had a fully developed system of writing; its complexity and state of development indicates an earlier period of development, which is still unattested. Bronze casting and pottery also advanced in Shang culture. The bronze was commonly used for art rather than weapons. In astronomy, the Shang astronomers saw Mars and various comets. Many musical instruments were also invented at that time.

Shang influence, though not political control, extended as far northeast as modern Beijing, where early pre-Yan culture shows evidence of Shang material culture.[7] At least one burial in this region during the Early Shang period contained both Shang-style bronzes and local-style gold jewelry.[7] This Shang influence likely made possible the integration of Yan into the later Zhou Dynasty.[7]

The Shang king, in his oracular divinations, repeatedly shows concern about the fang groups, which represented barbarians outside of the civilized tu regions that made up the Shang center. In particular, the tufang group of the Yan Shan region is regularly mentioned as hostile to the Shang[7]. The discovery of a Chenggu-style ge dagger-axe at Xiaohenan demonstrates that even at this early stage of Chinese history, there was some level of connection between the distant areas of north China.[7]

Shang Zhou, the last Yin king, committed suicide after his army was defeated by the Zhou people. Legends say that his army betrayed him by joining the Zhou rebels in a decisive battle.

A classical novel Fengshen Yanyi is about the war between the Yin and Zhou, in which each was favored and supported by one group of gods.

After the Yin's collapse, the surviving Yin ruling family collectively changed their surname from their royal Zi (子) (pinyin: zi; Wade-Giles: tzu) to the name of their fallen dynasty, Yin (殷). The family remained aristocratic and often provided needed administrative services to the succeeding Zhou Dynasty. The King Cheng of Zhou (周成王) through the Regent, his uncle the Duke Dan of Zhou (周公旦), enfeoffed the former Shang King Zhou's brother the ruler of Wei, WeiZi (微子) in the former Shang capital at Shang (商) with the territory becoming the state of Song (宋). The State of Song and the royal Shang descendants maintained rites to the dead Shang kings which lasted until 286 BC. (Source: Records of the Grand Historian.)

Both Korean and Chinese legends state that a disgruntled Yin prince named Jizi (箕子), who had refused to cede power to the Zhou, left China with his garrison and founded Gija Joseon near modern day Liaoning to what would become one of the early Korean states (Go-, Gija-, and Wiman-Joseon).

Many Shang clans migrated northeast and were integrated into Yan culture during the Western Zhou period. These clans maintained an elite status, continuing their sacrificial and burial traditions.[7]

Late and Early Shang

Written records found at Anyang confirm the existence of the Shang dynasty. However, Western scholars are hesitant to associate some settlements contemporaneous with the Anyang settlement with the Shang dynasty.[8] For example, archaeological findings at Sanxingdui suggest a technologically advanced civilization culturally unlike Anyang but lacking writing. The extent of Shang control is difficult to determine, given the lack of archaeological exploration. It is accepted among historians that Yin, ruled by the same Shang of official history, coexisted and traded with other culturally diverse settlements in North China.

Chinese historians living in later periods were accustomed to the notion of one dynasty succeeding another, but the actual political situation in early China may have been more complicated. The Xia and the Shang can possibly refer to political entities that existed concurrently, just as the early Zhou (successor state of the Shang), is known to have existed at the same time as the Shang.[7] This approach to the Sandai (Or Three Dynasties) system was promoted by noted archaeologist Kwang-chih Chang.

Furthermore, though the ruins of Yinxu confirms the existence of the Late Shang dynasty, no evidence has been unearthed proving the existence of the Shang dynasty before its move to its last capital. This is seen in research by the reference to Yin-era Shang as Late Shang and pre-jiaguwen Shang as Early Shang. The difficulty is less one of conspirators trying to legitimize the Shang Dynasty and more the problem of historians and archaeologists sorting out historical societies and pre-historic (That is, pre-writing) archeological cultures.

At the Shang Dynasty site of Ao, large walls were erected in the 15th century BC that had dimensions of 20 meters / 65 feet in width at the base and enclosed an area of some 2100 yards squared.[9] In similar dimensions, the ancient Chinese capital for the State of Zhao, Handan (founded in 386 BC), had walls that were again 20 meters / 65 feet wide at the base, a height of 15 meters / 50 feet tall, with two separate sides of its rectangular enclosure measured at a length of 1530 yards.[9]

Economy

As far back as c. 1500 BC, the early Shang Dynasty engaged in large-scale production of bronze-ware vessels and weapons.[10] This production necessitated large labor force that would handle the mining, refining, and transportation of copper, tin, and lead ores.[10] The Shang Dynasty royal court and aristocrats required a vast amount of different bronze vessels for various ceremonial purposes and events of religious divination, hence the need for official managers that could provide oversight and employment of hard-laborers and skilled artisans and craftsmen.[10] With the increased amount of bronze available, the army could become better equipped with an assortment of bronze weaponry, and bronze was also able to furnish the fittings of spoke-wheeled chariots that came into widespread use by 1200 BC.[11]

Apart from their role as the head military commanders, Shang kings also asserted their social supremacy by acting as the high priest of society and leader of divination ceremonies.[11] As the oracle bone texts reveal, the Shang kings were viewed as the best qualified members of society to offer sacrifices to their royal ancestors, to the high god Di, who in their beliefs was responsible for the rain, wind, and thunder.[11]

Shang Military

Shang infantry were armed with a variety of stone or bronze weaponry, including máo spears, yuè pole-axes, ge pole-based dagger-axes, the compound bow, and bronze or leather helmets (Wang Hongyuan 1993).[12] Their western military frontier was at the Taihang Mountains, where they fought the ma or "horse" barbarians, who might have used chariots. The Shang themselves likely only used chariots as mobile command vehicles or elite symbols.[13] Although the Shang depended upon the military skills of their nobility, the masses of town dwelling and rural commoners provided the Shang rulers with conscript labor as well as military obligation when mobilized for ventures of defense or conquest.[14] The subservient lords of noble lineage and other state rulers were obligated to furnish their locally-kept forces with all the necessary equipment, armor, and armaments, while the Shang king maintained a force of about a thousand troops at his capital, and personally led this force into battle.[15] A rudimentary military bureaucracy was needed in order to muster troops of three to five thousand troops in border campaigns, while it was recorded that up to thirteen thousand troops were mustered in order to suppress uprisings of insolent states to Shang authority.[15]

The army was divided into three sections - left, right, and middle.[12] There were largely two types of army units in these sections, those being the loosely organized infantry that were conscripted from the privileged populace and played a supporting role, while the core of the army was the warrior nobility who rode in chariots.[12] Chariot-based warfare continued as a prime means of conducting battle well into the Warring States (481 BC-221 BC) period, although this was slowly phased out by massive infantry, and then large cavalry-based forces by the 3rd century BC.[16] However, even after the Shang integrated the chariot into their military forces, the nobility were still largely amassed in infantry form, as the chariot was mostly associated with transportation, ceremonies, and large-scale royal hunting expeditions.[16] Chariots in the Shang period generally carried three men, the driver placed at the center, an archer on the left, and a warrior armed with a dagger-axe on the right.[16] It had a rectangular frame, with two large spoked wheels, and was driven by two horses,[16] although some of the chariots had teams of four horses.[11]

Shang artwork from the Shanghai Museum

A bronze liu ding ritual vessel

A bronze gong ritual vessel

A bronze gefuding gui vessel

A bronze yuefu you vessel

A bronze zun ritual vessel

Sovereigns of the Shang Dynasty

| Posthumous names | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convention: posthumous name or King + posthumous name | ||||

| Order | Reign | Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Notes |

| 01 | 29 | 湯 | Tāng | a Sage king; overthrew tyrant Jié (桀) of Xià (夏) |

| 02 | 02 | 太丁 | Tài Dīng | |

| 03 | 32 | 外丙 | Wài Bǐng | |

| 04 | 04 | 仲壬 | Zhòng Rén | |

| 05 | 12 | 太甲 | Tài Jiǎ | |

| 06 | 29 | 沃丁 | Wò Dǐng | |

| 07 | 25 | 太庚 | Tài Gēng | |

| 08 | 17 | 小甲 | Xiǎo Jiǎ | |

| 09 | 12 | 雍己 | Yōng Jǐ | |

| 10 | 75 | 太戊 | Tài Wù | |

| 11 | 11 | 仲丁 | Zhòng Dīng | |

| 12 | 15 | 外壬 | Wai Ren | |

| 13 | 09 | 河亶甲 | Hé Dǎn Jiǎ | |

| 14 | 19 | 祖乙 | Zǔ Yǐ | |

| 15 | 16 | 祖辛 | Zǔ Xīn | |

| 16 | 20 | 沃甲 | Wò Jiǎ | |

| 17 | 32 | 祖丁 | Zǔ Dīng | |

| 18 | 29 | 南庚 | Nán Gēng | |

| 19 | 07 | 陽甲 | Yáng Jiǎ | |

| 20 | 28 | 盤庚 | Pán Gēng | Shang finally settled down at Yīn (殷). The period starting from Pán Gēng is also called the Yīn Dynasty, beginning the golden age of the Shāng dynasty. Oracle bone inscriptions are thought to date at least to Pán Gēng's era. |

| 21 | 29 | 小辛 | Xiǎo Xīn | |

| 22 | 21 | 小乙 | Xiǎo Yǐ | |

| 23 | 59 | 武丁 | Wǔ Dīng | married to consort Fu Hao, who was a renowned warrior. Most of the oracle bones studied are believed to have came from his reign. |

| 24 | 12 | 祖庚 | Zǔ Gēng | |

| 25 | 20 | 祖甲 | Zǔ Jiǎ | |

| 26 | 06 | 廩辛 | Lǐn Xīn | |

| 27 | 06 | 庚丁 | Gēng Dīng | or Kang Ding (康丁 Kāng Dīng) |

| 28 | 35 | 武乙 | Wǔ Yǐ | |

| 29 | 11 | 文丁 | Wén Dīng | |

| 30 | 26 | 帝乙 | Dì Yǐ | |

| 31 | 30 | 帝辛 | Dì Xīn | aka Zhòu (紂), Zhòu Xīn (紂辛) or Zhòu Wáng (紂王). Also referred to by adding "Shāng" (商) in front of any of these names. |

Note:

|

||||

Further reading

- Timperley, Harold J. The Awakening of China in Archaeology; Further Discoveries in Ho-Nan Province, Royal Tombs of the Shang Dynasty, Dated Traditionally from 1766 to 1122 B.C.. 1936.

See also

- Chinese historiography

- Chinese sovereign

- Chinese mythology

- Erligang culture

- Xia Shang Zhou Chronology Project

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Fairbank 33.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fairbank, 34.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fairbank, 34–35.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Fairbank, 35.

- ↑ Sun 1989, 161-167.

- ↑ Chen 2002, 67-71.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Sun, Yan (June 2006). "Colonizing China's Northern Frontier: Yan and Her Neighbors During the Early Western Zhou Period". International Journal of Historical Archaeology 10 (2): 159-177(19). DOI:10.1007/s10761-006-0005-3. Research Blogging.

- ↑ (1999) The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press, 124-125. ISBN ISBN 0521470307.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 43.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Ebrey, 17.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Ebrey, 14.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Sawyer, 35.

- ↑ Shaughnessy, Edward L. Historical Perspectives on The Introduction of The Chariot Into China. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Jun., 1988), pp. 189-237

- ↑ Sawyer, 33.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Sawyer, 34.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Sawyer, 36.

References

- Chen, Yan (2002). Maritime Silk Route and Chinese-Foreign Cultural Exchanges. Beijing: Peking University Press. ISBN 7-301-03029-0.

- Fairbank, John King and Merle Goldman (1992). China: A New History; Second Enlarged Edition (2006). Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01828-1

- Keightley, David N. (1978). Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China. University of California Press, Berkeley. Large format hardcover, ISBN 0-520-02969-0 (out of print); A 1985 paperback 2nd edition is still in print, ISBN 0-520-05455-5.

- Keightley, David N. (2000). The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China (ca. 1200 – 1045 B.C.). China Research Monograph 53, Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California – Berkeley. ISBN 1-55729-070-9, ppbk.

- Lee, Yuan-Yuan and Shen, Sin-yan. (1999). Chinese Musical Instruments (Chinese Music Monograph Series). Chinese Music Society of North America Press. ISBN 1-880464039

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Sawyer, Ralph D. and Mei-chün Lee Sawyer (1994). Sun Tzu's The Art of War. New York: Barnes and Noble Inc. ISBN 1566192978

- Shen, Sinyan (1987), Acoustics of Ancient Chinese Bells, Scientific American, 256, 94.

- Sun, Guangqi (1989). History of Navigation in Ancient China. Beijing: Ocean Press. ISBN 7-5027-0532-5.

- Sun, Yan. 2006. "Colonizing China's Northern Frontier:Yan and Her Neighbors During the Early Western Zhou Period." International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 10, no. 2: 159-177.

- Wang, Hongyuan 王宏源 (1993). The Origins of Chinese Characters 漢字字源入門. Sinolingua, Beijing, ISBN 7-80052-243-1, ppbk.