Archive:New Draft of the Week: Difference between revisions

imported>Milton Beychok m (Fiinshed transclusion of new nominee) |

imported>Daniel Mietchen |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| <!-- article --> Earth's atmosphere | | <!-- article --> Earth's atmosphere | ||

| <!-- score --> | | <!-- score --> 3 | ||

| <!-- supporters --> [[User:Milton Beychok|Milton Beychok]] | | <!-- supporters --> [[User:Milton Beychok|Milton Beychok]] | ||

| <!-- specialist supporters --> | | <!-- specialist supporters --> [[User:Daniel Mietchen|Daniel Mietchen]] | ||

| <!-- date created --> August 18, 2009 | | <!-- date created --> August 18, 2009 | ||

Revision as of 19:35, 19 August 2009

The New Draft of the Week is a chance to highlight a recently created Citizendium article that has just started down the road of becoming a Citizendium masterpiece.

It is chosen each week by vote in a manner similar to that of its sister project, the Article of the Week.

Add New Nominees Here

To add a new nominee or vote for an existing nominee, click edit for this section and follow the instructions

| Nominated article | Vote Score |

Supporters | Specialist supporters | Date created |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth's atmosphere | 3 | Milton Beychok | Daniel Mietchen | August 18, 2009 |

If you want to see how these nominees will look on the CZ home page (if selected as a winner), scroll down a little bit.

Transclusion of the above nominees (to be done by an Administrator)

- Transclude each of the nominees in the above "Table of Nominee" as per the instructions at Template:Featured Article Candidate.

- Then add the transcluded article to the list in the next section below, using the {{Featured Article Candidate}} template.

View Current Transcluded Nominees (after they have been transcluded by an Administrator)

The next New Draft of the Week will be the article with the most votes at 1 AM UTC on Thursday, 27 August 2009. I did the honors this time. Milton Beychok 23:37, 19 August 2009 (UTC)

| Nominated article | Supporters | Specialist supporters | Dates | Score | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This article is about Earth's atmosphere. For other uses of the term Atmosphere, please see Atmosphere (disambiguation).

This article is about Earth's Atmosphere. For other uses of the term Earth, please see Earth (disambiguation).

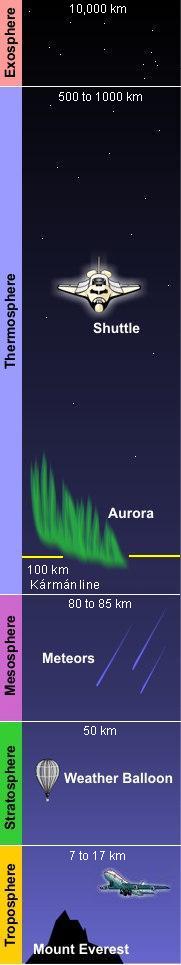

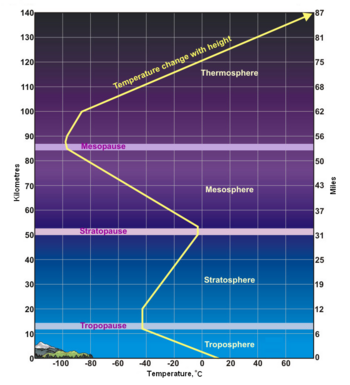

(PD) Photo: Courtesy of the Image Science & Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center Atmospheric gases scatter blue light more than other wavelengths, giving the Earth a blue halo when seen from space at an altitude of 181 nautical miles (335 kilometres) above the Earth. The Earth's atmosphere is an envelope of gas that surrounds the Earth and extends from the Earth's surface out thousands of kilometres, becoming increasingly thinner (less dense) with distance but always held in place by Earth's gravitational pull. The atmosphere contains the air we breathe and it holds clouds of moisture (water vapor) that become the water we drink. It protects us from meteors and harmful solar radiation and warms the Earth's surface by heat retention. In effect, the atmosphere is an envelope that protects all life on Earth. The atmosphere is a mixture of gases we call "air". On a dry volume basis, it consists of about 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen. The remainder of about 1% contains argon, carbon dioxide and very small amounts of other gases. The atmosphere is rarely, if ever, completely dry. Water vapor is almost always present up to about 4% of the total volume. In desert regions, when dry winds are blowing, water vapor in the air will be nearly zero. This climbs in other regions to about 3% on extremely hot and humid days. The upper limit, approaching 4%, is for tropical areas. The atmosphere has a total mass of about 5 × 1015 metric tons[1] and about 80% of that mass is within about 12 kilometres (7.5 miles) from the Earth's surface. There is no definite boundary between the atmosphere and outer space. It slowly becomes less dense (i.e., more empty) and fades into the void of outer space. Structure of the atmosphereAs shown in the adjacent diagram, Earth's atmosphere has five primary layers, referred to as spheres. From the lowest to the highest layer, they are the Troposphere, Stratosphere, Mesosphere, Thermosphere and the Exosphere. The four boundaries between the primary layers, referred to as pauses, are the Tropopause, Stratopause, Mesopause and the Thermopause. In more detail:[2]

There are two other regions of the atmosphere that deserve discussion, one is the Ionosphere and the other is the Ozone layer:

Sometimes the Earth's atmosphere is defined as consisting of these two parts:[11][12]

Pressure profile of the atmosphereEarth's atmospheric pressure at sea level is commonly taken to be 101,325 pascals and it decreases with increasing altitude. There are two equations for calculating the atmospheric pressure at any given altitude up to 86 kilometres (53 miles). Equation 1 is used when the lapse rate[13] is not equal to zero and equation 2 is used when the lapse rate equals zero:[14] The two equations are valid for seven different altitude regions of the Earth's atmosphere by using the designated base values (from the adjacent table) for , , and for each of the seven regions:[14][15]

For example, the atmospheric pressure at an altitude of 10,000 metres is obtained as 26,437 pascals by using Equation 1 and the appropriate base values for the altitude region number 1.

Composition of the atmospheric airThe adjacent table lists the concentration of 14 gases present in filtered dry air. Two of the gases, nitrogen and oxygen make up 99.03 percent of the clean, dry air. The other listed gases total to 0.97 percent. Note the amounts of greenhouse gases that are present: water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone. Additional gases (not listed in the table) are also present in very minute amounts. The atmospheric air is rarely, if ever, dry. Water vapor is nearly always present up to about 4% of the total volume. In the deserts regions, when dry winds are blowing, the water vapor content will be near zero. This climbs to near 3% on extremely hot/humid days. The upper limit of 4% is for tropical climates. Unfiltered air contains minute amounts of various types of particulate matter derived from sources such as from dust, pollen and spores, sea spray, volcanoes, meteoroids and industrial activities. Brief history of Earth's atmosphereEarth was formed 4.54 billion years ago (within an uncertainty of 1%) with a primordial gaseous atmosphere surrounding a very dense, molten core.[17][18][19][20] About 4.4 billion year ago, as the Earth began to cool and form a crust, the primordial atmosphere was stripped away by a combination of heat from that molten crust, periods of intense solar activity, and the solar wind. As the crust formed, volcanic activity became incessant. The outgassing from the volcanoes replaced the primordial atmosphere with what is referred to as the second atmosphere that most probably consisted of water vapor (steam), nitrogen, methane, ammonia, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, sulfur dioxide, and other gases — a mixture much like that emitted from volcanoes today. The dominant gases of the secondary atmosphere were water vapor, carbon dioxide and nitrogen. There was very little free oxygen (if any) in that secondary atmosphere and it would have been poisonous for almost all modern life forms. At about 4.0 billion years ago, cooling of the Earth and its atmosphere caused precipitation of the atmospheric water vapor as rainfall and subsequently the development of the Earth's oceans. Most of the atmospheric carbon dioxide was dissolved in the oceans and then precipitated out as solid carbonates. By about 3.5 billion years ago, life emerged in the oceans in the form of single-celled microorganisms (referred to as archaea). By about 2.7 billion year ago, the archaea were joined by microorganisms called cyanobacteria which were the first organisms to produce free gaseous oxygen. It took a long time for the cyanobacteria to get started but between 2.2 and 2.7 billion years ago, the Earth's atmosphere had been converted from an oxygen-lacking (anoxic) atmosphere to an oxygen-containing (oxic) atmosphere. This is often referred to as the Great Oxidation and it resulted in the mass extinction of any life forms that may have existed during the era of the anoxic atmosphere. Between then and now, the gaseous atmosphere was converted to its modern composition as presented and discussed in the previous section of this article. The evolution of the Earth's modern oxygen-containing atmosphere (referred to as the third atmosphere) led to the formation of the ozone layer which protects life on earth by blocking the harmful incoming ultraviolet solar radiation. References

|

Milton Beychok | 1

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Current Winner (to be selected and implemented by an Administrator)

To change, click edit and follow the instructions, or see documentation at {{Featured Article}}.

| The metadata subpage is missing. You can start it via filling in this form or by following the instructions that come up after clicking on the [show] link to the right. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

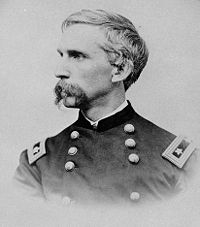

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, usually called "Lawrence", (1828-1914) was an American educator, who taught in a wide variety of fields, but was also an exceptionally distinguished citizen-soldier in the American Civil War. At Appomattox Court House, he was given the honor of accepting the Confederate flags, but did so, without orders, in a way that started healing for both sides.

Especially in his home state of Maine, he is also remembered for his four terms as Governor. As governor, he made statewide contributions to education, but his most intense were as a faculty member and then President of Bowdoin College.

Personality

He was an emotionally complex man, with a complex marriage. He was widely respected as a self-made war hero, a creative and beloved educator, and an elected official and political appointee without the right sort of personality for politics. Still, he served four terms as Governor of Maine. Of all his titles, however — Governor and academic President — he was proudest of General, and preferred to be addressed as such; he even sought foreign military service[1]

It is complex to judge whether he had an unusual desire for recognition and honors. Compared to some Civil War leaders such as George Armstrong Custer, he could be called extremely modest, but he also, even when he thought he might be dying of his wounds, was aggressive in seeking promotion in rank. One biographer suggests that his desire to perpetuate his own image was equally a desire to perpetuate the spirit of the Union's army, and its patriotism and suffering. "As the story of his life is pursued, the impression grows that he thought of himself as more than himself."[2]

Early life

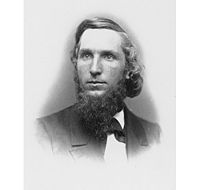

Brought up on his parents' farm, his father wanted him to join the military while his mother aimed him for the clergy. Since he chose to attend Bowdoin College, which, at the time, had a strong Congregationalist influence, perhaps his mother had the last word.

Before attending Bowdoin, he had to meet a requirement of proficiency in the Greek language, so, already having learned French and Latin, he taught himself Greek and was accepted and started there in 1848. He was a respected general student, and also a musician, who taught voice, led choirs, and played the bass viola.[3]

Preparing for marriage

They had first met as children, but, in his third year at Bowdoin, in 1851, he became seriously interested in Fannie Adams, adopted daughter of the respected minister of the First Parish Church, George Adams, who was her biological uncle. Joshua was 22, and a student who had not yet established a career, while the 25-year-old Fanny had a reputation as an exceptionally talented musician. She appeared, at first, puzzled by the intensity of his courtship. [4]

George Adams and Joshua Chamberlain had quite different views of Fanny, and Adams did not, at first, consider Chamberlain a good match for his daughter. For example, Adams considered her too independent and thought her taste for expensive clothing was immodest. Chamberlain, however, was attracted to her wit, independence and intelligence. Few pictures of Fanny survive, but accounts describe her as much more strikingly attractive than the pictures, and a theme of romantic physicality was evident in their correspondence.[5]

After his graduation, he enrolled in Bangor Theological Seminary, but stayed in contact with Fanny. At the seminary, his languages expanded to German, Arabic, Hebrew and Syriac. These studies were to prepare him for the Congregational ministry, which Fanny had already rejected. [6]

Fannie was in an increasingly uncomfortable situation. Her adoptive mother had died, and, six months later, her father married Helen Root, who was only a few months older than Fannie. Fannie resented her father's short period of mourning, offering enough anger that Adams suggested she live elsewhere. Helen, like Fannie, delighted in her appearance, but what Adams considered extravagance on Fannie's part seemed charming to him in Helen.

Some historians, such as Perry, believe Fanny was an early feminist, although one reviewer questions his research.[7] Even now, it is difficult to look into intimate relationships, and, at the time, such things were rarely spoken even among the participants.

When Fannie realized she had to leave the house, without independent income, she decided to spend three years teaching in the south, a respectable quasi-missionary role at the time. She went to teach at the Milledgeville Academy in Georgia in December 1852. Chamberlain also worried that she was reexamining his relations with him. Perry wrote she confided fears of intimacy to Chamberlain, both in person and in correspondence during her three years of teaching: "asking him if he thought that 'it' — it is unclear if she meant childbirth or sexual union — and saying she thought it might be 'better' for the two of them to forgo any intimacy.[8]

They married in December 1855.

Bowdoin faculty

He joined the Bowdoin College faculty in 1856, first with a professorship in logic and natural theology, then adding rhetoric and oratory, and eventually professor of modern languages. Early in his career, he developed a distinct philosophy of education:

My idea of a College course is that it should afford a liberal education - not a special or professional one, not in any way one-sided. It cannot be a finished education, but should be, I think, a general outline of a symmetrical development, involving such acquaintance with all the departments of knowledge and culture - proportionate to their several values - as shall give some insight into the principles and powers by which thought passes into life - together with such practice and exercise in each of the great fields of study that the student may experience himself a little in all.[9]

In spite of objections from her father, he married Fanny, starting a what was generally considered a lifelong love affair.[10] They had five children, two of whom survived into adulthood. Another historian, however, suggests their marriage may have had problems; [11] there clearly was a confrontation in 1868.

American Civil War

Volunteering for service in 1862, he declined, initially, a regimental command. He became lieutenant colonel of the 20th Maine Regiment, taking command in May 1863, and was promoted to colonel on August 8. His brother Tom also served in the regiment, as a junior officer.

He fought with the 20th at the Battles of Antietam, Shepherdstown Ford, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. He suffered his first wound at Fredericksburg.

Little Round Top

For performance in combat, however, he is most remembered for the Battle of Gettysburg, and the Little Round Top engagement. Immediately prior to the battle, and after Chancellorsville, he received a detail of men who had contracted to fight only with the 2nd Maine, and whose enlistments had expired. He was sympathetic to their plight, writing about it to the Governor.[12] he faced the difficult command task of speaking to soldiers, Accused of mutiny, tThey were involuntarily assigned to the 20th. "Chamberlain's brief speech and his pledge to plead their case caused all but a handful to take arms and join the ranks of the 20th for the coming battle".

At Little Round Top, the 20th held the end of the Union flank, in a desperate defense ending in an all-out bayonet charge against the 15th Alabama Regiment. Indeed, it was tactically critical; it has also become a legend in American military history; Chamberlain was to become a key character in Michael Shaara's historical novel The Killer Angels, the basis for a number of books, continued by Shaara's son, and for the Turner Broadcasting film and miniseries, in which he was played by Jeff Daniels. The character of his sergeant, Buster Kilrain, was fictional, but the Shaara material is highly regarded.

Not a moment was about to be lost! Five minutes more of such a defensive and the last roll call would sound for us! Desperate as the chances were, there was nothing for it but to take the offensive. I stepped to the colors. The men turned towards me. One word was enough- 'BAYONETS!' It caught like fire and swept along the ranks. The men took it up with a shout, one could not say whether from the pit or the song of the morning sat, it was vain to order 'Forward!'. No mortal could have heard it in the mighty hosanna that was winging the sky. The whole line quivered from the start; the edge of the left-wing rippled, swung, tossed among the rocks, straightened, changed curve from scimitar to sickle-shape; and the bristling archers swooped down upon the serried host- down into the face of half a thousand! Two hundred men![13]

There have been some suggestions that one of his junior officers originally started the bayonet charge, but there is little question Chamberlain committed all his forces to it, and was wounded in combat.

Petersburg

In November 1863 he was relieved from field service and sent to Washington suffering from malaria, the eventual cause of his death. He returned to the 20th, commanding it in the First Battle of Cold Harbor and the Battle of Petersburg, in which he was wounded; Ulysses S. Grant spot-promoted him to brigadier general, although he was expected to die.

The wound suffered at Petersburg damaged his bladder and urethra. In surgery later called "miraculous" by a U.S. Army surgeon in 1997, two regimental surgeons went into his abdomen, almost a death sentence by infection in 1864, and repaired the damage.[14] The technology available for urethral repair was very limited, and he required repeated surgeries for what probably partially impaired his sexual function. Normally, this detail would be outside the scope of a historical article, but it may have been an contributing factor to tension with his wife while Governor. [15]

Higher command

He returned to brigade command in November, and fought in the Overland Campaign in the Battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, North Anna and Second Petersburg. Wounded at the Rives' Salient engagement at Second Petersburg, he was again expected to die, and again spot-promoted by Grant, this time to major general. By the final days, he led a division.

A time to heal

At Appomattox Court House, he was given the honor, a sad one, of accepting the formal surrender of Confederate troops. As Confederate Gen. John Gordon's troops passed, Chamberlain, without orders, called his troops to attention and gave formal recognition to fellow soldiers, fellow citizens again. This was long remembered as a healing act, about which Chamberlain wrote in the lengthy Passing of the Armies.

I resolved to mark it by some token of recognition, which could be no other than a salute of arms. Well aware of the responsibility assumed, and of the criticisms that would follow, as the sequel proved, nothing of that kind could move me in the least. The act could be defended, if needful, by the suggestion that such a salute was not to the cause for which the flag of the Confederacy stood, but to its going down before the flag of the Union. My main reason, however, was one for which I sought no authority nor asked forgiveness. Before us in proud humiliation stood the embodiment of manhood: men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve; standing before us now, thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking level into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond; — was not such manhood to be welcomed back into a Union so tested and assured?

...Gordon at the head of the column, riding with heavy spirit and downcast face, catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up, and, taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command, gives word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position of the manual, — honor answering honor. On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer, nor word nor whisper of vain-glorying, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead!

As each successive division masks our own, it halts, the men face inward towards us across the road, twelve feet away; then carefully "dress" their line, each captain taking pains for the good appearance of his company, worn and half starved as they were. The field and staff take their positions in the intervals of regiments; generals in rear of their commands. They fix bayonets, stack arms; then, hesitatingly, remove cartridge-boxes and lay them down. Lastly, — reluctantly, with agony of expression, — they tenderly fold their flags, battle-worn and torn, blood-stained, heart-holding colors, and lay them down; some frenziedly rushing from the ranks, kneeling over them, clinging to them, pressing them to their lips with burning tears. And only the Flag of the Union greets the sky! [16]

While this gained him status on a national level, it was later to throw question on him when he later entered Republican politics in Maine. No one with secret sympathies for the South could be trusted by the Radical Republicans that controlled the Maine party.[17]

An April 1865 letter to his wife, reflecting on the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, also reveals his affection for, and a very sensual image of her. [18]

Postwar and politics

He rode in the formal end-of-war review, ended his service in August 1865, although he was reactivated so he could receive surgery for his war wounds. While he returned to the Bowdoin faculty, he also began to lecture about the Civil War. In August 1865, Grant made a visit to the Bowdoin commencement and stayed at Chamberlain's home. The visit was one of a number by Grant, which suggested a campaign tour, but the obvious endorsement of Chamberlain by Grant suggested he could be a strong Republican candidate for governor. Grant had principally come, however, not to meet with Chamberlain, but with O.O. Howard, another retired general and head of the Freedmen's Bureau [19] Maine's Republican leader, James G. Blaine, first saw Chamberlain as a strong gubernatorial candidate: a popular war hero who rose by his abilities, and came from a part of Maine that most avoided regional dislikes. Blaine, however, did not know Chamberlain's political weaknesses: "He did not have the skill necessary to move easily and gracefully out of difficult or embarrassing situations. Although adept at self-promotion in many ways, he would later shrink from initiating and running a political campaign in his own behalf. He lacked the thick, protective, rhinoceros hide that a politician needs. And where matters of principle were concerned, he had little talent for compromise...he would speak and act according to his own beliefs."[20]

Shortly afterward, their seven-month-old daughter died, the third child to die in infancy. For their tenth wedding anniversary on December 7, 1865, he gave her a bracelet that has become an artifact of American jewelers, centered about the insignia of the corps he commanded, with inscriptions of his battles and the shoulder boards of his rank. The marriage, however, was strained by the time he had spent away, the death of a child, and his continuing pain and restlessness from his wound. Chamberlain chose to run for Governor of Maine as a new adventure, without her agreement. [21] Well after the war, Congress explicitly voted him the Medal of Honor; it was not one of the questionable awards that did not meet the modern standards of the Pyramid of Honor. He was also governor of Maine, but his beloved Bowdoin College was first in his heart.

The long wartime separation from Fanny introduced tensions into their marriage, exacerbated by the political career in which she had no role. On November 19, 1868, a member of his staff in the Governor's Mansion told him that Fanny was telling neighbors he was pulling her hair and striking her, and she was planning to sue for divorce. The next day, he wrote a manuscript letter in the Bowdoin collection talking not about the specific allegations but the situation. It appeared to lead to reconciliation three years later back at Bowdoin. [22] A friend suggested she was preparing for divorce, to which Chamberlain responded,[23]

The thing comes to this, if you are contemplating any such things as Mr Johnson says—there is a better way to do it. If you are not, you must see the gulf of misery to which this confidence with unworthy people tends. You have this advantage of me, that I never spoke unkindly of you to any person. I shall not now do so to you. But it is a very great trial to me—more than all things else put together—wounds, pains, toils, wrongs, + hatred of eager enemies"

Issues as governor

Aside from the partisan issues, Chamberlain was not on the popular side in several issues:

- Prohibition

- Capital punishment

- Reconstruction

Additional politics

Return to Bowdoin

He preferred education to politics, and in 1871 became president of Bowdoin College. At a 2003 dedication of a memorial to him, the current college president, Barry Mills as "'thankless and wasteful'." Hardly the feelings of a man who felt appreciated, but also hardly the feelings of anyone assembled here today!" Bowdoin, a small but influential school, in Mills' words, "can trace much of its modern identity to the controversial Chamberlain presidency."

Even though it was a competitor, Chamberlain was instrumental in forming the University of Maine.

Back in office, he instituted controversial reforms. Perhaps based on his respect for Fannie's intellect, he was quite open to admitting women, and regretted Bowdoin did not currently have facilities for women. He did encourage an applicant in 1872. [24] Bowdoin eventually became coeducational, but he was less successful in introducing military drill as a means of enhancing spirit and discipline, as well as establishing a cadre of officers if needed. [25]

Chamberlain took a college steeped in the traditions of a classical curriculum and urged it to consider practical and technical education. In his inaugural address he pushed the College to "...accept immediately the challenge of the times," by placing a new emphasis on science and by replacing Greek and Latin with French and German. In the same speech, Chamberlain had the audacity to suggest that women too should "...have part in [the] high calling" represented by a Bowdoin education - an "innovation" that would take another century to materialize.

As president, Chamberlain set out to reform the strict and outdated student code of discipline. He eliminated mandatory morning and evening prayers and Saturday classes. He encouraged the faculty to be more accessible to students both inside and outside the classroom. And he established something near and dear to the hearts of each of his successors: an endowment for the College. where he restructured the college curriculum to include science and engineering.[26]

Retirement

During her later years, Fanny, who had been an artist in her youth, became more isolated as she lost her sight.

U.S. Army Legacy

A descendant, Bill Chamberlain, commanded a U.S. Army battalion in the Gulf War in 1990. In its preparation for the assault, MG Barry McCaffrey had taken the senior commanders of the 24th Mechanizing through an exhausting 36 hour command post map exercise ("Map-Ex"), which left them knowing their plans perfectly. Still, it was tiring; told McCaffrey: "Sir, I just want to say I would rather be shot in combat than go through another Map-Ex." A fellow battalion commander agreed, "I, too, would rather see Bill shot than go through another Map-Ex." [27]

In 1992, at the Command and General Staff College of the U.S. Army, lieutenant colonel Boyd M. Lewis wrote a new edition of the Army's Field Manual 22-100 : Military Leadership, and cited Chamberlain as an exemplar at both the tactical and strategic levels. The tactical described the Little Round Top action in terms relevant to contemporary officer training.

On Little Round Top, COL Chamberlain told his company commanders the purpose and importance of their mission. He ordered the right flank company to tie in with the 83d Pennsylvania and the left flank company to anchor on a large boulder. His thoughts turned to his left flank. There was nothing there except a small hollow and the rising slope of Big Round Top. The 20th Maine was literally at the end of the line.

COL Chamberlain then showed a skill common to good tactical leaders. He imagined threats to his unit, did what he could to guard against them, and considered what he would do to meet other possible threats. Since his left flank was open, COL Chamberlain sent B Company, commanded by CPT Walter G. Morrill, off to guard it and "act as the necessities of battle required." The captain positioned his men behind a stone wall that would face the flank of any Confederate advance. There, fourteen soldiers from the 2d US Sharpshooters, who had been separated from their unit, joined them.

The 20th Maine had been in position only a few minutes when the soldiers of the 15th and 47th Alabama attacked. The Confederates had also marched all night and were tired and thirsty. Even so, they attacked ferociously.

The Maine men held their ground, but then one of COL Chamberlain’s officers reported seeing a large body of Confederate soldiers moving laterally behind the attacking force. COL Chamberlain climbed on a rock—exposing himself to enemy fire—and saw a Confederate unit moving around his exposed left flank. If they outflanked him, his unit would be pushed off its position and destroyed. He would have failed his mission.

COL Chamberlain had to think fast. The tactical manuals he had so diligently studied called for a maneuver that would not work on this terrain. The colonel had to create a new maneuver, one that his soldiers could execute, and execute now.

...The decision left COL Chamberlain with another problem: there was nothing in the tactics book about how to get his unit from their L-shaped position into a line of advance. Under tremendous fire and in the midst of the battle, COL Chamberlain again called his commanders together. He explained that the regiment’s left wing would swing around "like a barn door on a hinge" until it was even with the right wing. Then the entire regiment, bayonets fixed, would charge downhill, staying anchored to the 83d Pennsylvania on its right. The explanation was clear and the situation clearly desperate.

When COL Chamberlain gave the order, 1LT Holman Melcher of F Company leaped forward and led the left wing downhill toward the surprised Confederates. COL Chamberlain had positioned himself at the boulder at the center of the L. When the left wing was abreast of the right wing, he jumped off the rock and led the right wing down the hill. The entire regiment was now charging on line, swinging like a great barn door—just as its commander had intended.[28]

At the strategic level, "Joshua Chamberlain’s greatest contribution to our nation may have been not at Gettysburg or Petersburg, but at Appomattox. By that time a major general, Chamberlain was chosen to command the parade at which GEN Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia laid down its arms and colors. GEN Grant had directed a simple ceremony that recognized the Union victory without humiliating the Confederates. However, MG Chamberlain sensed the need for something even greater. Instead of gloating as the vanquished army passed, he directed his bugler to sound the commands for attention and present arms. His units came to attention and rendered a salute, following his order out of respect for their commander, certainly not out of sudden warmth for recent enemies. That act set the tone for reconciliation and reconstruction and marks a brilliant leader, brave in battle and respectful in peace, who knew when, where, and how to lead."[29]

Unfortunately, Lewis died days after publication, so he could not be asked why he picked Chamberlain and George Patton. It suprises many that the two had many common traits, and surprises more that the two successful military leaders were so different in so many ways. [30]

The tradition continues. A descendant, Dennis Chamberlain, was a first lieutenant in the Arizona National Guard in 2009. [31]

References

- ↑ Joshua L. Chamberlain to King William of Prussia, Augusta, Maine: Bowdoin College Digital Archive, July 20, 1870

- ↑ John J. Pullen (1999), Joshua Chamberlain: a hero's life and legacy, Stackpole Books, ISBN 0811708861, p. 14

- ↑ Joshua Chamberlain - Maine's Favorite Son, Wicked Good Maine

- ↑ Diane M. Smith (1999), Fanny and Joshua: The Enigmatic Lives of Frances Caroline Adams and Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, Thomas Publications, ISBN 157747046X, pp. 20-22

- ↑ Mark Perry (1997), Conceived in Liberty: Joshua Chamberlain, William Oates, and the American Civil War, Viking, ISBN 0670862258, pp. 68-70

- ↑ Smith, Fanny and Joshua, p. 39

- ↑ Ethan S. Rafuse (July, 1998), (Book review) Conceived in Liberty: Joshua Chamberlain, William Oates, and the American Civil War, H-CivWar

- ↑ Perry, pp. 91-93

- ↑ (Letter) Joshua L. Chamberlain to Nehemiah Cleaveland,, Bowdoin College Digital Archive, 14 October 1859

- ↑ Jeremiah E. Goulka and James M. McPherson, ed. (2003), The Grand Old Man of Maine: Selected Letters of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, 1865-1914, University of North Carolina Press

- ↑ Smith, Fanny and Joshua, pp. 194-196

- ↑ From Joshua L. Chamberlain to Governor [Abner Coburn,], Bowdoin College Digital Archive, 25 May 1863

- ↑ Col. Chamberlain & the 20th Maine Infantry, Battle of Gettysburg Virtual Tour, National Park Service

- ↑ Reckling, Frederick W.; McAllister, Charles K. (May 2000 - Volume 374 - Issue - pp 107-114), The Career and Orthopaedic Injuries of Joshua L. Chamberlain: The Hero of Little Roundtop (Abstract), "Section I: Symposium: History of Orthopaedics in North America", Current Orthopaedic Practice

- ↑ Pullen, pp. 15 and 112 | Google Books preview, showing page 15 depicting details of the surgery and some of it aftermath.

- ↑ Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, The passing of the armies : an account of the final campaign of the Army of the Potomac, based upon personal reminiscences of the Fifth army corps

- ↑ Pullen, pp. 19-20 | Google Books preview, full-text of pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Joshua L. Chamberlain to "My Darling Wife" [Fanny Chamberlain], Burkeville, [Virginia]: Bowdoin College Digital Archive, 19 April 1865

- ↑ Perry, pp. 313-315, 317

- ↑ Pullen, pp. 17-19 | Google Books preview, full-text of pp. 17-19.

- ↑ Perry, pp. 315-316

- ↑ Pullen, p. 112

- ↑ Joshua L. Chamberlain to "Dear Fanny" [Fanny Chamberlain], Augusta: Bowdoin College, November 20, 1868

- ↑ Joshua L. Chamberlain to "Miss Low" [C.F. Low,], Brunswick, Maine: Bowdoin College Digital Archive, October 9, 1872

- ↑ Boards of Trustees and Overseers to "Dear Sir"[Joshua L. Chamberlain], Bowdoin College: Bowdoin College Digital Archive, November 12, 1873

- ↑ "Greetings from the College by President Barry Mills; Joshua Chamberlain Memorial Dedication", Bowdoin College News, 31 May 2003

- ↑ U.S. News & World Report (1992), Triumph without Victory: the History of the Persian Gulf War, Random House, pp. 282-283

- ↑ , CHAPTER 1: The Army Leadership Framework, Field Manual 22-100 : Military Leadership, U.S. Army

- ↑ , CHAPTER 7: Strategic Leadership, Field Manual 22-100 : Military Leadership, U.S. Army

- ↑ Pullen, pp. 179-183

- ↑ Collins, Elizabeth M. (2009), "In 'the shadow of a mighty presence': a family legacy", Soldiers Magazine 64 (8): 36

Previous Winners

The Sporting Life (album): A 1994 studio album recorded by Diamanda Galás and John Paul Jones. [e] (August 13}

The Sporting Life (album): A 1994 studio album recorded by Diamanda Galás and John Paul Jones. [e] (August 13} The Rolling Stones: Famous and influential English blues rock group formed in 1962, known for their albums Let It Bleed and Sticky Fingers, and songs '(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction' and 'Start Me Up'. [e] (August 5)

The Rolling Stones: Famous and influential English blues rock group formed in 1962, known for their albums Let It Bleed and Sticky Fingers, and songs '(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction' and 'Start Me Up'. [e] (August 5) Euler angles: three rotation angles that describe any rotation of a 3-dimensional object. [e] (July 30)

Euler angles: three rotation angles that describe any rotation of a 3-dimensional object. [e] (July 30) Chester Nimitz: United States Navy admiral (1885-1966) who was Commander in Chief, Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas in World War II [e] (July 23)

Chester Nimitz: United States Navy admiral (1885-1966) who was Commander in Chief, Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas in World War II [e] (July 23) Heat: A form of energy that flows spontaneously from hotter to colder bodies that are in thermal contact. [e] (July 16)

Heat: A form of energy that flows spontaneously from hotter to colder bodies that are in thermal contact. [e] (July 16) Continuum hypothesis: A statement about the size of the continuum, i.e., the number of elements in the set of real numbers. [e] (July 9)

Continuum hypothesis: A statement about the size of the continuum, i.e., the number of elements in the set of real numbers. [e] (July 9) Hawaiian alphabet: The form of writing used in the Hawaiian Language [e] (July 2)

Hawaiian alphabet: The form of writing used in the Hawaiian Language [e] (July 2) Now and Zen: A 1988 studio album recorded by Robert Plant, with guest contributions from Jimmy Page. [e] (June 25)

Now and Zen: A 1988 studio album recorded by Robert Plant, with guest contributions from Jimmy Page. [e] (June 25) Wrench (tool): A fastening tool used to tighten or loosen threaded fasteners, with one end that makes firm contact with flat surfaces of the fastener, and the other end providing a means of applying force [e] (June 18)

Wrench (tool): A fastening tool used to tighten or loosen threaded fasteners, with one end that makes firm contact with flat surfaces of the fastener, and the other end providing a means of applying force [e] (June 18) Air preheater: A general term to describe any device designed to preheat the combustion air used in a fuel-burning furnace for the purpose of increasing the thermal efficiency of the furnace. [e] (June 11)

Air preheater: A general term to describe any device designed to preheat the combustion air used in a fuel-burning furnace for the purpose of increasing the thermal efficiency of the furnace. [e] (June 11) 2009 H1N1 influenza virus: A contagious influenza A virus discovered in April 2009, commonly known as swine flu. [e] (June 4)

2009 H1N1 influenza virus: A contagious influenza A virus discovered in April 2009, commonly known as swine flu. [e] (June 4) Gasoline: A fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines derived from petroleum crude oil. [e] (21 May)

Gasoline: A fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines derived from petroleum crude oil. [e] (21 May) John Brock: Fictional British secret agent who starred in three 1960s thrillers by Desmond Skirrow. [e] (8 May)

John Brock: Fictional British secret agent who starred in three 1960s thrillers by Desmond Skirrow. [e] (8 May) McGuffey Readers: A set of highly influential school textbooks used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the elementary grades in the United States. [e] (14 Apr)

McGuffey Readers: A set of highly influential school textbooks used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the elementary grades in the United States. [e] (14 Apr) Vector rotation: Process of rotating one unit vector into a second unit vector. [e] (7 Apr)

Vector rotation: Process of rotating one unit vector into a second unit vector. [e] (7 Apr) Leptin: Hormone secreted by adipocytes that regulates appetite. [e] (31 Mar)

Leptin: Hormone secreted by adipocytes that regulates appetite. [e] (31 Mar) Kansas v. Crane: A 2002 decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, ruling that a person could not be adjudicated a sexual predator and put in indefinite medical confinement, purely on assessment of an emotional disorder, but such action required proof of a likelihood of uncontrollable impulse presenting a clear and present danger. [e] (24 Mar)

Kansas v. Crane: A 2002 decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, ruling that a person could not be adjudicated a sexual predator and put in indefinite medical confinement, purely on assessment of an emotional disorder, but such action required proof of a likelihood of uncontrollable impulse presenting a clear and present danger. [e] (24 Mar) Punch card: A term for cards used for storing information. Herman Hollerith is credited with the invention of the media for storing information from the United States Census of 1890. [e] (17 Mar)

Punch card: A term for cards used for storing information. Herman Hollerith is credited with the invention of the media for storing information from the United States Census of 1890. [e] (17 Mar) Jass–Belote card games: A group of trick-taking card games in which the Jack and Nine of trumps are the highest trumps. [e] (10 Mar)

Jass–Belote card games: A group of trick-taking card games in which the Jack and Nine of trumps are the highest trumps. [e] (10 Mar) Leptotes (orchid): A genus of orchids formed by nine small species that exist primarily in the dry jungles of South and Southeast Brazil. [e] (3 Mar)

Leptotes (orchid): A genus of orchids formed by nine small species that exist primarily in the dry jungles of South and Southeast Brazil. [e] (3 Mar) Worm (computers): A form of malware that can spread, among networked computers, without human interaction. [e] (24 Feb)

Worm (computers): A form of malware that can spread, among networked computers, without human interaction. [e] (24 Feb) Joseph Black: (1728 – 1799) Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide [e] (11 Feb 2009)

Joseph Black: (1728 – 1799) Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide [e] (11 Feb 2009) Sympathetic magic: The cultural concept that a symbol, or small aspect, of a more powerful entity can, as desired by the user, invoke or compel that entity [e] (17 Jan 2009)

Sympathetic magic: The cultural concept that a symbol, or small aspect, of a more powerful entity can, as desired by the user, invoke or compel that entity [e] (17 Jan 2009) Dien Bien Phu: Site in northern Vietnam of a 1954 decisive battle that soon forced France to relinquish control of colonial Indochina. [e] (25 Dec)

Dien Bien Phu: Site in northern Vietnam of a 1954 decisive battle that soon forced France to relinquish control of colonial Indochina. [e] (25 Dec) Blade Runner: 1982 science fiction film directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford, set in an imagined Los Angeles of 2019. [e] (25 Nov)

Blade Runner: 1982 science fiction film directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford, set in an imagined Los Angeles of 2019. [e] (25 Nov) Piquet: A two-handed card game played with 32 cards that originated in France around 1500. [e] (18 Nov)

Piquet: A two-handed card game played with 32 cards that originated in France around 1500. [e] (18 Nov) Crash of 2008: the international banking crisis that followed the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007. [e] (23 Oct)

Crash of 2008: the international banking crisis that followed the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007. [e] (23 Oct)- Information Management: Add brief definition or description (31 Aug)

Battle of Gettysburg: A turning point in the American Civil War, July 1-3, 1863, on the outskirts of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. [e] (8 July)

Battle of Gettysburg: A turning point in the American Civil War, July 1-3, 1863, on the outskirts of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. [e] (8 July) Drugs banned from the Olympics: Substances prohibited for use by athletes prior to, and during competing in the Olympics. [e] (1 July)

Drugs banned from the Olympics: Substances prohibited for use by athletes prior to, and during competing in the Olympics. [e] (1 July) Sea glass: Formed when broken pieces of glass from bottles, tableware, and other items that have been lost or discarded are worn down and rounded by tumbling in the waves along the shores of oceans and large lakes. [e] (24 June)

Sea glass: Formed when broken pieces of glass from bottles, tableware, and other items that have been lost or discarded are worn down and rounded by tumbling in the waves along the shores of oceans and large lakes. [e] (24 June) Dazed and Confused (Led Zeppelin song): Landmark 1969 song recorded by Led Zeppelin for their eponymous debut album, which became an early centrepiece for the group's live performances. [e] (17 June)

Dazed and Confused (Led Zeppelin song): Landmark 1969 song recorded by Led Zeppelin for their eponymous debut album, which became an early centrepiece for the group's live performances. [e] (17 June) Hirohito: The 124th and longest-reigning Emperor of Japan, 1926-89. [e] (10 June)

Hirohito: The 124th and longest-reigning Emperor of Japan, 1926-89. [e] (10 June) Henry Kissinger: (1923—) American academic, diplomat, and simultaneously Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs and Secretary of State in the Nixon Administration; promoted realism (foreign policy) and détente with China and the Soviet Union; shared 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for ending the Vietnam War; Director, Atlantic Council [e] (3 June)

Henry Kissinger: (1923—) American academic, diplomat, and simultaneously Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs and Secretary of State in the Nixon Administration; promoted realism (foreign policy) and détente with China and the Soviet Union; shared 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for ending the Vietnam War; Director, Atlantic Council [e] (3 June) Palatalization: An umbrella term for several processes of assimilation in phonetics and phonology, by which the articulation of a consonant is changed under the influence of a preceding or following front vowel or a palatal or palatalized consonant. [e] (27 May)

Palatalization: An umbrella term for several processes of assimilation in phonetics and phonology, by which the articulation of a consonant is changed under the influence of a preceding or following front vowel or a palatal or palatalized consonant. [e] (27 May) Intelligence on the Korean War: The collection and analysis, primarily by the United States with South Korean help, of information that predicted the 1950 invasion of South Korea, and the plans and capabilities of the enemy once the war had started [e] (20 May)

Intelligence on the Korean War: The collection and analysis, primarily by the United States with South Korean help, of information that predicted the 1950 invasion of South Korea, and the plans and capabilities of the enemy once the war had started [e] (20 May) Trinity United Church of Christ, Chicago: A predominantly black church located in south Chicago with upwards of 10,000 members, established in 1961. [e] (13 May)

Trinity United Church of Christ, Chicago: A predominantly black church located in south Chicago with upwards of 10,000 members, established in 1961. [e] (13 May) BIOS: Part of many modern computers responsible for basic functions such as controlling the keyboard or booting up an operating system. [e] (6 May)

BIOS: Part of many modern computers responsible for basic functions such as controlling the keyboard or booting up an operating system. [e] (6 May) Miniature Fox Terrier: A small Australian vermin-routing terrier, developed from 19th Century Fox Terriers and Fox Terrier types. [e] (23 April)

Miniature Fox Terrier: A small Australian vermin-routing terrier, developed from 19th Century Fox Terriers and Fox Terrier types. [e] (23 April) Joseph II: (1741–1790), Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the Hapsburg (Austrian) territories who was the arch-embodiment of the Enlightenment spirit of the later 18th-century reforming monarchs. [e] (15 Apr)

Joseph II: (1741–1790), Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the Hapsburg (Austrian) territories who was the arch-embodiment of the Enlightenment spirit of the later 18th-century reforming monarchs. [e] (15 Apr) British and American English: A comparison between these two language variants in terms of vocabulary, spelling and pronunciation. [e] (7 Apr)

British and American English: A comparison between these two language variants in terms of vocabulary, spelling and pronunciation. [e] (7 Apr) Count Rumford: (1753–1814) An American born soldier, statesman, scientist, inventor and social reformer. [e] (1 April)

Count Rumford: (1753–1814) An American born soldier, statesman, scientist, inventor and social reformer. [e] (1 April) Whale meat: The edible flesh of various species of whale. [e] (25 March)

Whale meat: The edible flesh of various species of whale. [e] (25 March) Naval guns: Add brief definition or description (18 March)

Naval guns: Add brief definition or description (18 March) Sri Lanka: Add brief definition or description (11 March)

Sri Lanka: Add brief definition or description (11 March) Led Zeppelin: Add brief definition or description (4 March)

Led Zeppelin: Add brief definition or description (4 March) Martin Luther: Add brief definition or description (20 February)

Martin Luther: Add brief definition or description (20 February) Cosmology: Add brief definition or description (4 February)

Cosmology: Add brief definition or description (4 February) Ernest Rutherford: Add brief definition or description(28 January)

Ernest Rutherford: Add brief definition or description(28 January) Edinburgh: Add brief definition or description (21 January)

Edinburgh: Add brief definition or description (21 January) Russian Revolution of 1905: Add brief definition or description (8 January 2008)

Russian Revolution of 1905: Add brief definition or description (8 January 2008) Phosphorus: Add brief definition or description (31 December)

Phosphorus: Add brief definition or description (31 December) John Tyler: Add brief definition or description (6 December)

John Tyler: Add brief definition or description (6 December) Banana: Add brief definition or description (22 November)

Banana: Add brief definition or description (22 November) Augustin-Louis Cauchy: Add brief definition or description (15 November)

Augustin-Louis Cauchy: Add brief definition or description (15 November)- B-17: Add brief definition or description - 8 November 2007

Red Sea Urchin: Add brief definition or description - 1 November 2007

Red Sea Urchin: Add brief definition or description - 1 November 2007 Symphony: Add brief definition or description - 25 October 2007

Symphony: Add brief definition or description - 25 October 2007 Oxygen: Add brief definition or description - 18 October 2007

Oxygen: Add brief definition or description - 18 October 2007 Origins and architecture of the Taj Mahal: Add brief definition or description - 11 October 2007

Origins and architecture of the Taj Mahal: Add brief definition or description - 11 October 2007 Fossilization (palaeontology): Add brief definition or description - 4 October 2007

Fossilization (palaeontology): Add brief definition or description - 4 October 2007 Cradle of Humankind: Add brief definition or description - 27 September 2007

Cradle of Humankind: Add brief definition or description - 27 September 2007 John Adams: Add brief definition or description - 20 September 2007

John Adams: Add brief definition or description - 20 September 2007 Quakers: Add brief definition or description - 13 September 2007

Quakers: Add brief definition or description - 13 September 2007 Scarborough Castle: Add brief definition or description - 6 September 2007

Scarborough Castle: Add brief definition or description - 6 September 2007 Jane Addams: Add brief definition or description - 30 August 2007

Jane Addams: Add brief definition or description - 30 August 2007 Epidemiology: Add brief definition or description - 23 August 2007

Epidemiology: Add brief definition or description - 23 August 2007 Gay community: Add brief definition or description - 16 August 2007

Gay community: Add brief definition or description - 16 August 2007 Edward I: Add brief definition or description - 9 August 2007

Edward I: Add brief definition or description - 9 August 2007

Rules and Procedure

Rules

- The primary criterion of eligibility for a new draft is that it must have been ranked as a status 1 or 2 (developed or developing), as documented in the History of the article's Metadate template, no more than one month before the date of the next selection (currently every Thursday).

- Any Citizen may nominate a draft.

- No Citizen may have nominated more than one article listed under "current nominees" at a time.

- The article's nominator is indicated simply by the first name in the list of votes (see below).

- At least for now--while the project is still small--you may nominate and vote for drafts of which you are a main author.

- An article can be the New Draft of the Week only once. Nominated articles that have won this honor should be removed from the list and added to the list of previous winners.

- Comments on nominations should be made on the article's talk page.

- Any draft will be deleted when it is past its "last date eligible". Don't worry if this happens to your article; consider nominating it as the Article of the Week.

- If an editor believes that a nominee in his or her area of expertise is ineligible (perhaps due to obvious and embarrassing problems) he or she may remove the draft from consideration. The editor must indicate the reasons why he has done so on the nominated article's talk page.

Nomination

See above section "Add New Nominees Here".

Voting

- To vote, add your name and date in the Supporters column next to an article title, after other supporters for that article, by signing

<br />~~~~. (The date is necessary so that we can determine when the last vote was added.) Your vote is alloted a score of 1. - Add your name in the Specialist supporters column only if you are an editor who is an expert about the topic in question. Your vote is alloted a score of 1 for articles that you created and 2 for articles that you did not create.

- You may vote for as many articles as you wish, and each vote counts separately, but you can only nominate one at a time; see above. You could, theoretically, vote for every nominated article on the page, but this would be pointless.

Ranking

- The list of articles is sorted by number of votes first, then alphabetically.

- Admins should make sure that the votes are correctly tallied, but anyone may do this. Note that "Specialist Votes" are worth 3 points.

Updating

- Each Thursday, one of the admins listed below should move the winning article to the Current Winner section of this page, announce the winner on Citizendium-L and update the "previous winning drafts" section accordingly.

- The winning article will be the article at the top of the list (ie the one with the most votes).

- In the event of two or more having the same number of votes :

- The article with the most specialist supporters is used. Should this fail to produce a winner, the article appearing first by English alphabetical order is used.

- The remaining winning articles are guaranteed this position in the following weeks, again in alphabetical order. No further voting should take place on these, which remain at the top of the table with notices to that effect. Further nominations and voting take place to determine future winning articles for the following weeks.

- Winning articles may be named New Draft of the Week beyond their last eligible date if their circumstances are so described above.

- The article with the most specialist supporters is used. Should this fail to produce a winner, the article appearing first by English alphabetical order is used.

Administrators

The Administrators of this program are the same as the admins for CZ:Article of the Week.

References

See Also

- CZ:Article of the Week

- CZ:Markup tags for partial transclusion of selected text in an article

- CZ:Monthly Write-a-Thon

| Citizendium Initiatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Eduzendium | Featured Article | Recruitment | Subpages | Core Articles | Uncategorized pages | Requested Articles | Feedback Requests | Wanted Articles |

|width=10% align=center style="background:#F5F5F5"| |}

![{\displaystyle P=P_{b}\cdot \left[{\frac {T_{b}}{T_{b}+L_{b}\cdot (h-h_{b})}}\right]^{\textstyle {\frac {g\cdot M}{R\cdot L_{b}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a0bf08544e1a140969dae6359b67f791120f5190)

![{\displaystyle P=P_{b}\cdot \exp \left[{\frac {-\,g\cdot M\cdot (h-h_{b})}{R\cdot T_{b}}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e59f45ff65284fa6d5051aed5644e4a9383a5745)