Relative volatility: Difference between revisions

imported>Milton Beychok m (Added a {{Dambigbox}} template) |

imported>John Stephenson m (moved Relative volatility/Draft to Relative volatility: citable version policy) |

Revision as of 07:12, 15 September 2013

Relative volatility is a measure of the difference between the vapor pressure of the more volatile components of a liquid mixture and the vapor pressure of the less volatile components of the mixture. This measure is widely used in designing large industrial distillation processes.[1][2][3] In effect, it indicates the ease or difficulty of using distillation to separate the more volatile components from the less volatile components in a mixture. In other words, the higher is the relative volatility of a liquid mixture, the easier it is to separate the mixture components by distillation. By convention, relative volatility is typically denoted as .

Relative volatilities are used in the design of all types of distillation processes as well as other separation or absorption processes that involve the contacting of vapor and liquid phases in a series of equilibrium stages.

Relative volatilities are not used in separation or absorption processes that involve components that chemically react with each other (for example, the absorption of gaseous carbon dioxide in aqueous solutions of sodium hydroxide which yields sodium carbonate).

Relative volatility of binary liquid mixtures

For a liquid mixture of two components (called a binary mixture) at a given temperature and pressure, the relative volatility is defined as

| where: | |

| = the relative volatility of the more volatile component to the less volatile component | |

| = the vapor-liquid equilibrium concentration of component in the vapor phase | |

| = the vapor-liquid equilibrium concentration of component in the liquid phase | |

| = the vapor-liquid equilibrium concentration of component in the vapor phase | |

| = the vapor-liquid equilibrium concentration of component in the liquid phase | |

| = commonly called the K value or vapor-liquid distribution ratio of a component |

When their liquid concentrations are equal, more volatile components have higher vapor pressures than less volatile components. Thus, a value (= ) for a more volatile component is larger than a value for a less volatile component. That means that ≥ 1 since the larger value of the more volatile component is in the numerator and the smaller of the less volatile component is in the denominator.

The quantity is unitless. When the volatilities of both key components are equal, it follows that = 1 and separation of the two by distillation would be impossible under the given conditions. As the value of increases above 1, separation by distillation becomes progressively easier.

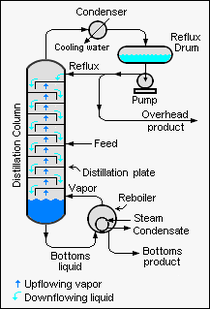

When a binary liquid mixture is distilled, complete separation of the two components is rarely achieved. Typically, the overhead fraction from the distillation column consists predominantly of the more volatile component and some small amount of the less volatile component and the bottoms fraction consists predominantly of the less volatile component and some small amount of the more volatile component.

Relative volatility of multi-component mixtures

A liquid mixture containing many components is called a multi-component mixture. When a multi-component mixture is is distilled, the overhead fraction and the bottoms fraction typically contain much more than one or two components. For example, some intermediate products in a petroleum refinery are multi-component liquid mixtures that may contain the alkane, alkene and alkyne hydrocarbons ranging from methane having one carbon atom to decanes having ten carbon atoms. For distilling such a mixture, the distillation column may be designed (for example) to produce:

- An overhead fraction containing predominantly the more volatile components ranging from methane (having one carbon atom) to propane (having three carbon atoms)

- A bottoms fraction containing predominantly the less volatile components ranging from isobutane (having four carbon atoms) to decanes (ten carbon atoms).

Such a distillation column is typically called a depropanizer. The column designer would designate the key components governing the separation design to be propane as the so-called light key (LK) and isobutane as the so-called heavy key (HK). In that context, a lighter component means a component with a lower boiling point (or a higher vapor pressure) and a heavier component means a component with a higher boiling point (or a lower vapor pressure).

Thus, for the distillation of any multi-component mixture, the relative volatility is often defined as

Large-scale industrial distillation is rarely undertaken if the relative volatility is less than 1.05.[2]

The values of have been correlated empirically or theoretically in terms of temperature, pressure and phase compositions in the form of equations, tables or graph such as the well-known DePriester charts.[4][5]

values are widely used in the design of large-scale distillation columns for distilling multi-component mixtures in petroleum refineries, petrochemical and chemical plants, natural gas processing plants and other industries.

Effect of temperature or pressure on relative volatility

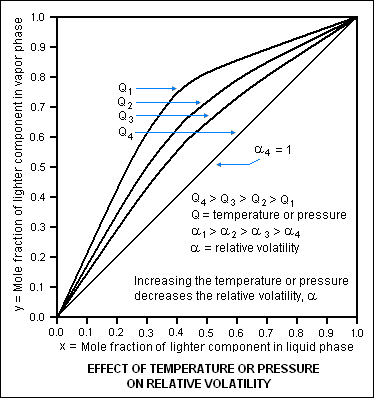

An increase in pressure has a significant effect on the relative volatility of the components in a liquid mixture. Since an increase in the pressure requires an increase in the temperature, then an increase in temperature also effects the relative volatility.

The diagram below is based on the vapor-liquid equilibrium of a hypothetical binary liquid mixture and illustrates how an increase in either the pressure or temperature decreases the relative volatility of the mixture. The diagram depicts four sets of vapor-liquid equilibrium for a hypothetical binary mixture of liquids (for example, acetone and water or butane and pentane), each set at a different condition of temperature and pressure. Since the relative volatility of a liquid mixture varies with temperature and pressure, each of the four sets is also at a different relative volatility. Condition 1 is at a temperature and pressure where the relative volatility of the hypothetical binary solution is high enough to make the distillation quite easy. As the temperature and/or pressure (Q in the diagram) increases from condition 1 to condition 4, the relative volatility (α in the diagram) decreases to a value of 1, and separation of the components by distillation is no longer possible since at that point there is no difference in the vapor pressures of the binary components. As can be seen in the diagram at α = 1, the mole fraction of the lighter (more volatile) component in the liquid phase is exactly the same as in the vapor phase which means that no separation is possible by distillation.

References

- ↑ Kister, Henry Z. (1992). Distillation Design, 1st Edition. McGraw-hill. ISBN 0-07-034909-6.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Perry, R.H. and Green, D.W. (Editors) (1984). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook, 6th Edition. McGraw-hill. ISBN 0-07-049479-7.

- ↑ Seader, J. D., and Henley, Ernest J. (1998). Separation Process Principles. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-58626-9.

- ↑ DePriester, C.L. (1953), Chem. Eng. Prog. Symposium Series, 7, 49, pages 1-43

- ↑ DePriester Charts

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- Editable Main Articles with Citable Versions

- CZ Live

- Engineering Workgroup

- Chemistry Workgroup

- Chemical Engineering Subgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- Engineering Content

- Chemistry Content

- Chemical Engineering tag