Naval warfare: Difference between revisions

imported>Gregory J. Kohs (→Britain and Royal Navy: Date and pages) |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz (links) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

In 17th-century Europe, maritime war was subordinate to land warfare. Few theorists paid attention to naval strategy or tactics. However, French writers began to produce works on naval doctrine, focusing on the defense of coasts and the defense of and attacks on maritime traffic. The English Admiralty meanwhile began to develop tactical fighting instructions for fleet actions, but not on strategies fleet actions would support. Late-17th-century maritime wars thus demonstrated the centrality of French doctrine, in which major naval campaigns were concerned with coastal defense and attacks on individual or small groups of ships. Maritime activity was therefore extended in pursuit of these campaigns and was only periodically punctuated by concentrated fleet battles. | In 17th-century Europe, maritime war was subordinate to land warfare. Few theorists paid attention to naval strategy or tactics. However, French writers began to produce works on naval doctrine, focusing on the defense of coasts and the defense of and attacks on maritime traffic. The English Admiralty meanwhile began to develop tactical fighting instructions for fleet actions, but not on strategies fleet actions would support. Late-17th-century maritime wars thus demonstrated the centrality of French doctrine, in which major naval campaigns were concerned with coastal defense and attacks on individual or small groups of ships. Maritime activity was therefore extended in pursuit of these campaigns and was only periodically punctuated by concentrated fleet battles. | ||

The [[Spanish Armada]] was a failed | The [[Spanish Armada]] was a failed seaborne invasion of England by Spain in 1588. The Armada included 130 large ships of 57,900 tons mounting 2,500 cannons and manned by 30,700 crewmen. The English fleet consisted of 197 vessels of 29,800 tons manned by 15,800 men. The problems of logistics, and the prevailing winds and currents in the English Channel, proved devastating for the Spanish, whose basic strategy was inheently flawed. A Spanish victory was highly improbable. There were six naval encounters, but none were decisive. What destroyed the Armada was stormy weather and disease. The defeat of the Armada was not decisive militarily but it did encourage English morale and undermine Spanish morale; it fatally weakened the Catholic League, and in reduced the respect of neutrals for Spain. | ||

==18th century== | ==18th century== | ||

Rodger goes beyond battle history and fleet operations to examine the organizational superiority of the Royal Navy, especially in contrast with the Frenc navy. He argues the British were better at ship architecture (gaining speed via bronze plating), maintanence, practical officer training, and crew care. British repair docks could handle ships of the line better than the French, who concentrated on construction rather than maintenance. Much credit goes to the Admiralty, under the direction of civilian [[Samuel Pepys]] as secretary and chief administrative officer.<ref> N. A. M. Rodger, ''The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815'' (2006)</ref> | Rodger goes beyond battle history and fleet operations to examine the organizational superiority of the Royal Navy, especially in contrast with the Frenc navy. He argues the British were better at ship architecture (gaining speed via bronze plating), maintanence, practical officer training, and crew care. British repair docks could handle ships of the line better than the French, who concentrated on construction rather than maintenance. Much credit goes to the Admiralty, under the direction of civilian [[Samuel Pepys]] as secretary and chief administrative officer.<ref> N. A. M. Rodger, ''The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815'' (2006)</ref> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 20: | ||

==21st century== | ==21st century== | ||

The information age has presented to us another transformation in naval warfare. Both World Wars and the [[Falklands War]] have shown that ships built for the sole purpose of firing guns at long range are vulnerable: to air attack, [[submarine]] attack, [[missile]] attack, and close-in engagements with vessels encountered unexpectedly at night or in fog. An answer to this vulnerability has been an increased | The information age has presented to us another transformation in naval warfare. Both World Wars and the [[Falklands War]] have shown that ships built for the sole purpose of firing guns at long range are vulnerable: to air attack, [[submarine]] attack, [[missile]] attack, and close-in engagements with vessels encountered unexpectedly at night or in fog. An answer to this vulnerability has been an increased dependence on electronics and a host of weapons systems for varying roles of defense. | ||

The American [[cruiser]] of World War Two has been replaced by modern Ticonderoga class cruisers now specializing in Anti-Air, Anti-Sub, and Anti-surface Warfare carried out almost solely by missiles, [[torpedo]]es, and ship-based [[helicopter]]s; destroyers and light escorts also only use gunnery as a secondary system The only conventional gun defenses are two 5-inchers and a "last-ditch" Phalanx [[close-in weapons system]] (CIWS). Even pure gun CIWS are being replaced or supplanted by point defense missiles such as the [[RIM-116 Rolling Airframe Missile]], or the Russian [[Kashtan]] hybrid missile-gun CIWS. So representative of technology's multi-role place in the modern navy, these 9,000-ton fossil-fueled missile cruisers have supplanted the 58,000-ton battleships of yesterday as the navy's flagships, highlighting the fiscal advantages of a larger fleet comprised of smaller, more capable boats. | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 23:31, 19 July 2008

Naval warfare considers the miltary history of the organized navies of the world from 300 BC to the present.

Ancient

Medieval

Early modern

In 17th-century Europe, maritime war was subordinate to land warfare. Few theorists paid attention to naval strategy or tactics. However, French writers began to produce works on naval doctrine, focusing on the defense of coasts and the defense of and attacks on maritime traffic. The English Admiralty meanwhile began to develop tactical fighting instructions for fleet actions, but not on strategies fleet actions would support. Late-17th-century maritime wars thus demonstrated the centrality of French doctrine, in which major naval campaigns were concerned with coastal defense and attacks on individual or small groups of ships. Maritime activity was therefore extended in pursuit of these campaigns and was only periodically punctuated by concentrated fleet battles.

The Spanish Armada was a failed seaborne invasion of England by Spain in 1588. The Armada included 130 large ships of 57,900 tons mounting 2,500 cannons and manned by 30,700 crewmen. The English fleet consisted of 197 vessels of 29,800 tons manned by 15,800 men. The problems of logistics, and the prevailing winds and currents in the English Channel, proved devastating for the Spanish, whose basic strategy was inheently flawed. A Spanish victory was highly improbable. There were six naval encounters, but none were decisive. What destroyed the Armada was stormy weather and disease. The defeat of the Armada was not decisive militarily but it did encourage English morale and undermine Spanish morale; it fatally weakened the Catholic League, and in reduced the respect of neutrals for Spain.

18th century

Rodger goes beyond battle history and fleet operations to examine the organizational superiority of the Royal Navy, especially in contrast with the Frenc navy. He argues the British were better at ship architecture (gaining speed via bronze plating), maintanence, practical officer training, and crew care. British repair docks could handle ships of the line better than the French, who concentrated on construction rather than maintenance. Much credit goes to the Admiralty, under the direction of civilian Samuel Pepys as secretary and chief administrative officer.[1]

19th century

The British navy's victory, under Admiral Horatio Nelson over the French fleet in the Battle of the Nile in 1798 thwarted Napoleon's attempt to cripple Britain and represents the most complete naval triumph of the 18th century and the apogee of naval warfare in the age of sail.

Rodger (2005) examines the implications of victory at sea during the Napoleonic wars and the impact that British naval success had on the ultimate defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815. Naval warfare in the early 19th century was almost never decisive; military engagements on land remained the most crucial determinant of success under arms. However, success at sea could contribute to wasting an enemy's resources via the destruction of technology (complex and costly warships) and skilled manpower. Naval engagements, because they were far removed from the presence of civilians, also had the advantage of arousing little, if any, resentment from civilian populations, resentment that could be transformed into popular uprisings and insurgency. Ultimately, Britain's Royal Navy, despite a string of naval victories, was unable to counter Napoleon's hegemony on the European continent. For that, a coalition of land powers was needed. Naval contributions remained but a sideshow throughout the conflict.[2]

The abolition of privateering by the Declaration of Paris in 1852 marks an important stage in the state monopolization of violence in the modern world. The Confederate States of America purchased raiders from Britain, but could not sell the prizes and could not get private interests to build privateers against the U.S. merchant fleet.

20th century

21st century

The information age has presented to us another transformation in naval warfare. Both World Wars and the Falklands War have shown that ships built for the sole purpose of firing guns at long range are vulnerable: to air attack, submarine attack, missile attack, and close-in engagements with vessels encountered unexpectedly at night or in fog. An answer to this vulnerability has been an increased dependence on electronics and a host of weapons systems for varying roles of defense.

The American cruiser of World War Two has been replaced by modern Ticonderoga class cruisers now specializing in Anti-Air, Anti-Sub, and Anti-surface Warfare carried out almost solely by missiles, torpedoes, and ship-based helicopters; destroyers and light escorts also only use gunnery as a secondary system The only conventional gun defenses are two 5-inchers and a "last-ditch" Phalanx close-in weapons system (CIWS). Even pure gun CIWS are being replaced or supplanted by point defense missiles such as the RIM-116 Rolling Airframe Missile, or the Russian Kashtan hybrid missile-gun CIWS. So representative of technology's multi-role place in the modern navy, these 9,000-ton fossil-fueled missile cruisers have supplanted the 58,000-ton battleships of yesterday as the navy's flagships, highlighting the fiscal advantages of a larger fleet comprised of smaller, more capable boats.

See also

- Naval guns

- American Revolution, naval history

- Military history

- Land warfare

- Marine Corps

- Alfred Thayer Mahan

- Sea Power

- United States Navy

- World War II, Pacific

Battles and campaigns

- Battle of Salamis 480 B.C.

- Battle of Lepanto. 1571

- Spanish Armada, 1588

- Battle of Trafalgar, 1805

- Union Blockade, U.S. Civil War 1861-65

- Battle of Monitor and Merrimac, 1862

- Battle of Tsushima, 1905

- Battle of Jutland, 1916

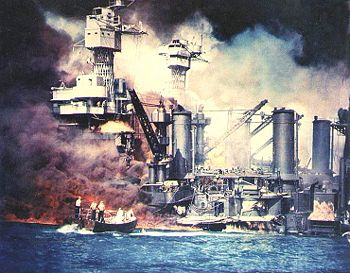

- Battle of Pearl Harbor, 1941

- Battle of Midway, 1942

- Battle of Philippine Sea, 1944

- Battle of Leyte Gulf, 1944

- Battle of Okinawa, 1945

Bibliography

Surveys

- Bruce, Anthony and Cogar, William. An Encyclopedia of Naval History. (1998). 440 pp.

- Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor N. Dupuy. Encyclopedia of Military History: From 3500 BC to the Present (1977) 1465pp; complete summary of a;l; major battles, campaigns and wars

- George, James L. History of Warships: From Ancient Times to the Twenty-First Century. (1998). 353 pp. and text search

- Humble, Richard. Naval Warfare: An Illustrated History. (1983). 304 pp, elementary survey

- Ireland, Bernard and Gibbons, Tony. Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail. (2000). 240 pp. excerpt and text search

- Keegan, John. The Price of Admiralty: The Evolution of Naval Warfare. (1989). 292 pp.

- Padfield, Peter. Maritime Supremacy and the Opening of the Western Mind: Naval Campaigns that Shaped the Modern World (2002) excerpt and text search

- Padfield, Peter. Maritime Power and the Struggle for Freedom: Naval Campaigns That Shaped the Modern World, 1788-1851. (2005). 480 pp.

- Potter, E. B. Sea Power: A Naval History (1982), covers all major battled in world history

- Rose, Susan. Medieval Naval Warfare, 1000-1500 (2002) online edition

- Rose, Susan. "Islam Versus Christendom: the Naval Dimension, 1000-1600." Journal of Military History 1999 63(3): 561-578. Issn: 0899-3718 Fulltext: in Jstor

- Sondhaus, Lawrence. Naval Warfare, 1815-1914 (2001) online edition

- Tucker, Spencer C. and Frederiksen, John, eds. Naval Warfare: An International Encyclopedia. 3 vol. (2002). 1,231 pp.

- Willmott, H. P. Sea Warfare: Weapons, Tactics and Strategy. (1982). 165 pp. short survey by leading historian

Major nations

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise And Fall of British Naval Mastery (1986) 405pp

- Rodger, N. A. M. The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain 660-1649 vol 1 (1999) 691pp; excerpt and text search

- Rodger, N. A. M. The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815 (2006), 976pp excerpt and text search

United States

- Howarth, Stephen. To Shining Sea -- A History of the United States Navy, 1775-1991 (1991).

- Love, Robert W. History of the US Navy: 1942-1991 (1992) excerpt and text search

- Love, Robert W. History of the US Navy: 1775-1941 (1992) excerpt and text search

Sea Power

- Koburger Jr. Charles W. Sea Power in the Twenty-First Century: Projecting a Naval Revolution (1997) online edition

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer. The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783 (1890) 557 pages; perhaps the most influential history book ever written Google version

Ships

- George, James L. History of Warships: From Ancient Times to the Twenty-First Century. (1998). 353 pp.; strong on details such as ship weights and armaments; and text search

- Ireland, Bernard, and Tony Gibbons. Jane's Battleships of the 20th Century (1996), technical details

- Ireland, Bernard, and Tony Gibbons. Jane's Naval Airpower(2003)

- Lautenshläger, Karl. "The Submarine in Naval Warfare, 1901-2001." International Security 1986-1987 11(3): 94-140. Issn: 0162-2889; important wide-ranging survey; Fulltext: in Jstor

- Parrish, Thomas. The Submarine: A History. (2004). 572 pp. excerpt and text search

Technology

See also Naval guns

- Brown, David K. Eclipse of the Big Gun: The Warship 1906-45 (1992)

- Friedman, Norman. U.S. Naval Weapons: Every Gun, Missile, Mine and Torpedo Used by the U.S. Navy from 1883 to the Present (1983), highly detailed guide

- Greene, Jack, and Alessandro Massignani. Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854-1891 (1998) online edition

- Guilmartin, John F., Jr. Gunpowder and Galleys: Changing Technology and Mediterranean Warfare at Sea in the Sixteenth Century (2003)

- Lambert, Nicholas A. Sir John Fisher's Naval Revolution (2002) excerpt and text search

- McBride, William M. Technological Change and the United States Navy, 1865-1945 (2000) excerpt and text search

- Morison, Elting E. Men Machines and Modern Times (1968) excerpt and text search

- Sumida, Jon Tetsuro. "A Matter of Timing: The Royal Navy and the Tactics of Decisive Battle, 1912–1916," Journal of Military History 67 (January 2003): 85–136 in JSTOR

Wars

Early Modern: 1500-1700

- Corbett, Julian S. Drake and the Tudor Navy: With a History of the Rise of England as a Maritime Power (1898) online edition vol 1; also online edition vol 2

- Palmer, M. A. J. "The 'Military Revolution' Afloat: The Era of the Anglo-Dutch Wars and the Transition to Modern Warfare at Sea." War in History April 1997, Vol. 4 Issue 2, pp 23-149, ISSN:0968-3445 in EBSCO Relates the Anglo-Dutch wars to the transition to modern warfare at sea with attention to the pressures of the military revolution and effects of technology to sea warfare.

18th century

- Allen, Gardner W. A Naval History of the American Revolution (1913) online at Google

- Fowler, William M. Rebels Under Sail (1976), the standard scholarly history of the naval warfare during the American Revolution

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. John Paul Jones (1959), Pulitzer Prize excerpt and text search

- Thomas, Evan. John Paul Jones: Sailor, Hero, Father of the American Navy (2003) excerpt and text search

Napoleonic

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer. The influence of sea power upon the War of 1812 2 vols (1905) online edition

- Pope, Dudley. Decision at Trafalgar. (1960) online edition

- Roosevelt, Theodore. The Naval War of 1812 (1882). eText at Project Gutenberg

20th century

- Lautenshläger, Karl. "The Submarine in Naval Warfare, 1901-2001." International Security 1986-1987 11(3): 94-140. Issn: 0162-2889; important wide-ranging survey; Fulltext: in Jstor

World War I

See also World War I

- Gray, Edwyn A. The U-Boat War, 1914-1918 (1994)

- Halpern, Paul G. A Naval History of World War I(1995)

- Hough, Richard. The Great War at Sea, 1914-1918. (1984). 353 pp.

- Marder, Arthur. From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: 5 vol. vol 1: The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904-1919; vol. 2: The War Years: To the Eve of Jutland (1966); vol. 3: Jutland and After: May 1916-December 1916 (1970); vol 4: 1917 Year of Crisis (197); vol. 5: Victory and Aftermath (January 1918-June 1919) (1970); the standard scholarly history

- Massie, Robert K. Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. (2003). 880 pp. excerpt and text search

World War II

See also World War II, Pacific

- Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan (1975).

- Buell, Thomas. Master of Seapower: A Biography of Admiral Ernest J. King (1976).

- Dunnigan, James F. and Nofi, Albert A. Victory at Sea: World War II in the Pacific. (1995). 576 pp.

- Gailey, Harry A. The War in the Pacific: From Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay (1995) online edition

- King, Ernest J. U.S. Navy at War, 1941-1945: Official Reports to the Secretary of the Navy (1946) online edition

- Kirby, S. Woodburn. The War Against Japan. 4 vols. (1957-1965). Highly detailed official Royal Navy history.

- Miller, Nathan. War at Sea: A Naval History of World War II. (1995). 576 pp. popular

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (1963), one-volume version of his massive 15 vol history (1947-62) of combat operations

- Potter, John D. Yamamoto 1967.

- Prange, Gordon W. At Dawn We Slept. 1982. Pearl Harbor

- Prange, Gordon W. Miracle at Midway (1982).

- Reynolds, Clark G. The Fast Carriers: Forging of an Air Navy (1968).

- Spector, Ronald. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan Free Press, 1985.

- Turnbull, Archibald D. and Clifford Lord. History of United States Naval Aviation (1949).

- Vandervat, Dan. The Atlantic Campaign: World War II's Great Struggle at Sea. (1988). 424 pp.

Cold war and after

- Brasher, Bart. Implosion: Downsizing the U.S. Military, 1987-2015 (2000) online edition

- Duncan, Francis. Rickover and the Nuclear Navy (1990).

- Hartmann, Frederick H. Naval Renaissance -- The U.S. Navy in the 1980s (1990).

- Lehman, John F., Jr. Command of the Seas: Building the 600 Ship Navy (1989).

- Love, Robert W. History of the US Navy: 1942-1991 (1992) excerpt and text search

- O'Brien, Phillips Payson, ed. Technology and Naval Combat in the Twentieth Century and Beyond. (2001). 272 pp.

- Ryan, Paul B. First Line of Defense -- The U.S. Navy Since 1945 (1981)