Faraday's law (electromagnetism): Difference between revisions

imported>Paul Wormer No edit summary |

imported>Paul Wormer |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

The electromotive force (EMF)<ref>The term EMF has historical origin, but is somewhat unfortunate as it is not a force but a potential.</ref> is defined as | The electromotive force (EMF)<ref>The term EMF has historical origin, but is somewhat unfortunate as it is not a force but a potential.</ref> is defined as | ||

where the electric field '''E''' is integrated around the closed path ''C''. | where the electric field '''E''' is integrated around the closed path ''C''. | ||

| Line 40: | Line 38: | ||

where ''c'' is the speed of light. If ''C'' is a conducting loop, then under influence of the EMF a current ''i''<sub>ind</sub> will run through it. The minus sign in Faraday's law has the consequence that the magnetic field generated by | where ''c'' is the speed of light. If ''C'' is a conducting loop, then under influence of the EMF a current ''i''<sub>ind</sub> will run through it. The minus sign in Faraday's law has the consequence that the magnetic field generated by | ||

''i''<sub>ind</sub> opposes the change in Φ; this phenomenon is known as [[Lenz' law]]. If the surface ''S'' is constant the change in Φ is solely due to a change in '''B'''. | ''i''<sub>ind</sub> opposes the change in Φ; this phenomenon is known as [[Lenz' law]]. If the surface ''S'' is constant the change in Φ is solely due to a change in '''B'''. | ||

==Connection to Maxwell's equation== | |||

Application of [[Stokes' theorem]] gives | |||

:<math> | |||

\oint_C \mathbf{E}\cdot d\mathbf{l} = \iint_S \big(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\times \mathbf{E}\big)\cdot d\mathbf{S}, | |||

</math> | |||

where ''S'' is a surface that has ''C'' as boundary. From rewriting Faraday's law as follows, | |||

:<math> | |||

\iint_S \big(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\times \mathbf{E}\big)\cdot d\mathbf{S} = -k\frac{d}{dt}\iint_{S} \mathbf{B}\cdot d\mathbf{S} = -k \iint_{S}\frac{\partial\mathbf{B}}{\partial t} \cdot d\mathbf{S} | |||

</math> | |||

and the fact that ''S'' is arbitrary, we may conclude | |||

:<math> | |||

\boldsymbol{\nabla}\times \mathbf{E} = -k\frac{\partial\mathbf{B}}{\partial t}, | |||

</math> | |||

which is one of [[Maxwell's equations]]. Recall that ''k'' = 1 for SI units and ''k'' = 1/''c'' for Gaussian units. | |||

==Connection to Lorentz force== | ==Connection to Lorentz force== | ||

Revision as of 09:46, 17 May 2008

In electromagnetism Faraday's law of magnetic induction states that a change in magnetic flux generates an electromotive force. The law is named after the English scientist Michael Faraday.

If one rotates a conducting loop in a static magnetic field, the magnetic flux through the surface of the loop is changed. This change induces an electromotive force (voltage difference) generating an electric current in the loop. Thus, the work done in rotating the loop inside a magnetic field is converted into an electric current. This, in brief, shows that Faraday's law forms the theoretical basis of the dynamo and the electric generator.

Mathematical formulation

The magnetic flux Φ through a surface S is defined as the surface integral

where dS is a vector normal to the infinitesimal surface element dS and dS is of length dS. The dot stands for the inner product between the magnetic induction B and dS. In vacuum the magnetic induction B is proportional to the magnetic field H. (In SI units: B = μ0 H with μ0 the magnetic constant of the vacuum; in Gaussian units: B = H.) Note, parenthetically, that the inner product between B and dS is zero if these two vectors are parallel and maximum (in absolute value) if they are orthogonal. So, by rotating one of the two vectors and keeping the other fixed one can change the magnetic flux.

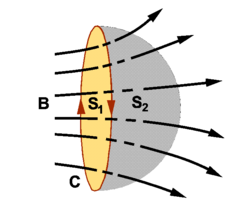

The flux through two surfaces that together form a closed surface is equal because of Gauss' law. Indeed, in the figure on the right the surfaces S1 and S2, which have the boundary C in common, form together a closed surface. Hence Gauss' law states that

where the minus sign of the first term is due to the fact that the flux is into the volume enveloped by the two surfaces. It follows that

and that the magnetic flux Φ can be computed with respect to any surface that has C as boundary.

The electromotive force (EMF)[1] is defined as

where the electric field E is integrated around the closed path C.

Faraday's law of magnetic induction relates the EMF to the time derivative of the magnetic flux, it reads:

where c is the speed of light. If C is a conducting loop, then under influence of the EMF a current iind will run through it. The minus sign in Faraday's law has the consequence that the magnetic field generated by iind opposes the change in Φ; this phenomenon is known as Lenz' law. If the surface S is constant the change in Φ is solely due to a change in B.

Connection to Maxwell's equation

Application of Stokes' theorem gives

where S is a surface that has C as boundary. From rewriting Faraday's law as follows,

and the fact that S is arbitrary, we may conclude

which is one of Maxwell's equations. Recall that k = 1 for SI units and k = 1/c for Gaussian units.

Connection to Lorentz force

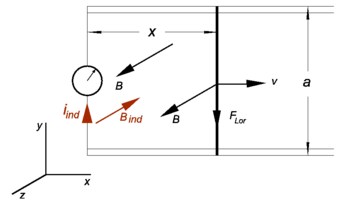

It is instructive to derive Faraday's law from the Lorentz force for a special case. To that end an experimental setup is depicted in the figure on the right. A conducting bar of length a moves in positive x direction over two parallel pairs of conducting rails. The speed v of the bar is constant. The whole setup is placed in a homogeneous magnetic field B = μ0 H (we are using SI units) that points toward the reader, i.e., in positive z-direction. Homogeneity means that everywhere in the plane of drawing a magnetic field B of the same strength points toward the reader.

The magnetic field is constant, but the surface S increases linearly in time

The vector B points in positive z-direction and so does the normal to S,

The time-dependence of the growing flux is solely due to the time-dependence of the growth of the surface. The time derivative of the magnetic flux in the figure is positive and equal to

The Lorentz force (in SI units) is the cross product,

In order to obtain the electromotive force (EMF) one must integrate the inner product of electric force with path, FLor⋅dl, counter-clockwise around the circuit consisting of the moving bar, the two pairs of unmoving rails and the unmoving conductor containing the ampmeter. The integration is counter-clockwise because of the right-hand screw rule applied to the direction of B. Except for the moving bar, where the force is constant and non-zero, there is no force in the circuit. The constant force acts over the length a of the moving bar and gives an EMF equal to force times path length,

From equations (1) and (2) follows

which indeed is Faraday's law of magnetic induction.

The EMF gives a current iind in the direction of the Lorentz force, i.e., in a clockwise direction in the plane of drawing (the x-y plane). By Biot-Savart's law a current gives a circular magnetic field. The current iind has a tangent vector in the x-y plane that is in negative z-direction. Hence Bind opposes B, in accordance with Lenz' law.

Note

- ↑ The term EMF has historical origin, but is somewhat unfortunate as it is not a force but a potential.