Complement (immunologic): Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz m (opsonin link) |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz m (Complement moved to Complement (immunologic): Disambiguation) |

Revision as of 23:00, 22 October 2008

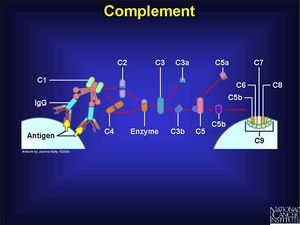

Complement, or the complement system, is a major part of immune response. It involves the interaction of at least 25 proteins, some of which initiate the complement response, amplify or modulate the response, and start a chain of complement protein conversions that result in proteins that attack cell membrates.

Ideally, these attacks are against invading cells, but they may attack the healthy cells of the body in an autoimmune disease. [2]

Complements are abbreviated C-number for the complement protein number; there may be suffixes to describe subclasses of a protein. Regulatory factor or enzymes are other proteins involved in the process, such as B for "Factor B" or C3 convertase for the enzyme that converts ordinary C3 to C3a.

Activation

Two main pathways lead to the activation of complement. The classic cascade is C1 and its subcomponents, which recognize an antigen on a cell wall, which triggers the "complement cascade".

The other starts with complement factor B binding to a cell surface, rather than to a specific antigen. This is the alternative or properdin pathway, which depends on Factor I, a circulating protein, which recognizes repeating sugar structures found in bacteria but not human cells.[3]

C3b, while part of the cascade, opsonizes bacteria, making them targets for phagocytosis. C5a also has this effect. [4]

Amplification and modulation

Both the classic and alternate pathways produce C3 convertase, which converts inactive C3 to its active form, C3b.

There are a number of microbial defense mechanisms that seek to avoid the consequences of complement activation. Schistosomes, for example, acquire sialic acid, which reduces the binding of C3b fragments that activate the alternative pathway. [5]

Membrane attack

At the end of the cascade, performin molecules are produced that will puncture the target cell, allowing free ion flows that destroy the cell. These are also called the membrane attack complex. [6] This is also caused by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. If complement attack blood vessels, however, their destruction causes the redness and swelling characteristic of inflammation. [3]

The thick cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria protects them from MAC-based lysis. Other bacteria activate the complex, but create a MAC that does not match their susceptible membranes. [5]

Biologic activity

Complement proteins cause a variety of biological effects.

| Substance | Effects | Process/receptors/cells affected |

|---|---|---|

| C3a | Smooth muscle contraction, increase of vascular permeability, and degranulation of mast cells and basophils causing histamine release | Smooth muscle, basophils, mast cells, platelets, eosinophils |

| C3b | Opsonization and making immune complexes soluble, to amplify later phagocytosis | |

| C3e | Release of leucocytes from blood marrow |

Disorders of complement protein deficiency

References

- ↑ National Cancer Institute, Slide 18: Complement, Understanding Cancer Series: The Immune System

- ↑ Joseph A. Bellanti (1985), Immunology III, W.B. Saunders, pp. 106-116

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ganong, William F. (Nineteenth edition, 1999), Review of Medical Physiology, Appleton & Lange,pp. 499

- ↑ , Roles of Phagocytosis, Conjoint 401-403, University of Washington

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Complement Modulation Strategies, Brown University

- ↑ How Complement Works, Brown University