Roots of American conservatism: Difference between revisions

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Pennsylvania" to "Pennsylvania") |

John Leach (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "China" to "China") |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

Throughout the immediate post-war years, a number of severe political shocks were delivered to the American body politic which conservatives were able to exploit to reinvigorate their movement. | Throughout the immediate post-war years, a number of severe political shocks were delivered to the American body politic which conservatives were able to exploit to reinvigorate their movement. | ||

In the late 1940s, the communists under [[Mao Tse-Tung]] came to power in | In the late 1940s, the communists under [[Mao Tse-Tung]] came to power in China and about the same time, the [[Union of Soviet Socialist Republics|USSR]] demonstrated its nuclear capability by exploding an [[atomic bomb]]. Many Americans could not understand how these events could have happened and their confusion and fears were only enhanced by charges that forces and people unfriendly to America were at work internally, including in the U.S. State Department, to aid and abet the [[communism|communist]] forces. The [[Alger Hiss|Hiss]] case and the sensational charges of [[Joseph McCarthy]] brought the issue of internal subversion to the forefront. | ||

Soon thereafter, the United States found itself in a stalemate military situation on the Korean peninsula which many conservatives felt was due to political interference, or worse, which was hampering the conduct of the war and hamstringing U.S. troops. When news came of a number of American POWs who had begun to cooperate with the communist enemy, it appeared to these same conservatives that the American educational system was dangerously flawed in that, accoring to them, it did not provide American students with an adequate understanding of the "principles, rights, and political forms they were supposed to defend in the Korean War" (Russell Kirk, ''The American Cause'')<ref>So as to drive home this point, later in that same book, Kirk states in support of this contention: "a subcommittee of the Senate concluded that the failure of our educational system to provide proper instruction in history, politics, economics, and other subjects was a principal cause of the bewildered and shameful conduct of the majority of American prisoners."</ref>. | Soon thereafter, the United States found itself in a stalemate military situation on the Korean peninsula which many conservatives felt was due to political interference, or worse, which was hampering the conduct of the war and hamstringing U.S. troops. When news came of a number of American POWs who had begun to cooperate with the communist enemy, it appeared to these same conservatives that the American educational system was dangerously flawed in that, accoring to them, it did not provide American students with an adequate understanding of the "principles, rights, and political forms they were supposed to defend in the Korean War" (Russell Kirk, ''The American Cause'')<ref>So as to drive home this point, later in that same book, Kirk states in support of this contention: "a subcommittee of the Senate concluded that the failure of our educational system to provide proper instruction in history, politics, economics, and other subjects was a principal cause of the bewildered and shameful conduct of the majority of American prisoners."</ref>. | ||

Revision as of 10:10, 28 February 2024

The term "conservative" did not enter American political discourse until well into the 19th century, but the principles were present long before.

Founding Fathers

The Loyalists of the American Revolution were mostly political conservatives, some of whom produced political discourse of a high order, including lawyer Joseph Galloway and governor-historian Thomas Hutchinson. After the war, the great majority remained in the U.S. and became citizens, but some leaders emigrated to other places in the British Empire. Samuel Seabury was a Loyalist who returned and as the first American bishop played a major role in shaping the Episcopal religion, a stronghold of conservative social values. However the Loyalist political tradition died out totally it the U.S.; it survives in Canadian conservatism.

The Founding Fathers created the single most important set of political ideas in American history, known as republicanism, which all groups, liberal and conservative alike, have drawn from. During the First Party System (1790s-1820s) the Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton, developed an important variation of republicanism that can be considered conservative. Rejecting monarchy and aristocracy, they emphasized civic virtue as the core American value. The Federalists spoke for the propertied interests and the upper classes of the cities. They envisioned a modernizing land of banks and factories, with a strong army and navy. George Washington was their great hero.

On many issues American conservatism also derives from the republicanism of Thomas Jefferson and his followers, especially John Randolph of Roanoke and his "Old Republicans" or "Quids." They idealized the yeoman farmer as the epitome of civic virtue, warned that banking and industry led to corruption, that is to the illegitimate use of government power for private ends. Jefferson himself was a vehement opponent of what today is called "judicial activism". [1] The Jeffersonians stressed States' Rights and small government.

Ante-Bellum: Calhoun and Webster

During the Second Party System (1830-54) the Whig Party attracted most conservatives, such as Daniel Webster of New England. Daniel Webster and other leaders of the Whig Party, called it the conservative party in the late 1830s. John C. Calhoun, a Democrat, articulated a sophisticated conservatism in his writings. Richard Hofstadter (1948) called him "The Marx of the Master Class." Calhoun argued that a conservative minority should be able to limit the power of a "majority dictatorship" because tradition represents the wisdom of past generations. (This argument echoes one made by Edmund Burke, the founder of British conservatism, in Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)). Calhoun is considered the father of the idea of minority rights, a position adopted by liberals in the 1960s in dealing with civil rights.

The conservatism of the antebellum period is contested territory; conservatives of the 21st century disagree over what comprises their heritage. Thus William J. Bennett (2006) a prominent conservative leader, warns conservatives to NOT honor Calhoun, Know-Nothings, Copperheads and 20th century isolationists.

Lincoln to Cleveland

Since 1865 the Republican party has identified itself with President Abraham Lincoln, who was the ideological heir of the Whigs and of both Jefferson and Hamilton. As the Gettysburg Address shows, Lincoln cast himself as a second Jefferson bringing a second birth of freedom to the nation that had been born 86 years before in Jefferson's Declaration. The Copperheads of the Civil War reflected a reactionary opposition to modernity of the sort repudiated by modern conservatives. A few libertarians have adopted a neo-Copperhead position, arguing Lincoln was a dictator who created an all-powerful government.

In the late 19th century the Bourbon Democrats, led by President Grover Cleveland, preached against corruption, high taxes (protective tariffs), and imperialism, and supported the gold standard and business interests. They were overthrown by William Jennings Bryan in 1896, who moved the mainstream of the Democratic Party permanently to the left.

The 1896 presidential election was the first with a conservative versus liberal theme in the way in which these terms are now understood. Republican William McKinley won using the pro-business slogan "sound money and protection," while Bryan's anti-bank populism had a lasting effect on economic policies of the Democratic Party.

William Graham Sumner, Yale professor (1872-1910) and polymath, vigorously promoted a libertarian conservative ethic. After dallying with Social Darwinism under the influence of Herbert Spencer, he rejected evolution in his later works, and strongly opposed imperialism. He opposed monopoly and paternalism in theory as a threat to equality, democracy and middle class values, but was vague on what to do about it.[2]

Early 20th century

In the Progressive Era (1890s-1932), regulation of industry expanded as conservatives led by Senator Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island were put on the defensive. However, Aldrich's proposal for a strong national banking system was enacted as the Federal Reserve System in 1913. Theodore Roosevelt, the dominant personality of the era, was both liberal and conservative by turns. As a conservative he led the fight to make the country a major naval power, and demanded entry into World War I to stop what he saw as the German attacks on civilization. William Howard Taft promoted a strong federal judiciary that would overrule excessive legislation. Taft defeated Roosevelt on that issue in 1912, forcing Roosevelt out of the GOP and turning it to the right for decades. As president, Taft remade the Supreme Court with five appointments; he himself presided as chief justice in 1921-30, the only former president ever to do so.

Pro-business Republicans returned to dominance in 1920 with the election of President Warren G. Harding. The presidency of Calvin Coolidge (1923-29) was a high water mark for conservatism, both politically and intellectually. Classic writing of the period includes Democracy and Leadership (1924) by Irving Babbitt and H.L. Mencken's magazine American Mercury (1924-33). The Efficiency Movement attracted many conservatives such as Herbert Hoover with its pro-business, pro-engineer approach to solving social and economic problems. In the 1920s many American conservatives generally maintained anti-foreign attitudes and, as usual, were disinclined toward changes to the healthy economic climate of the age.

During the Great Depression, other conservatives participated in the taxpayers' revolt at the local level. From 1930 to 1933, Americans formed as many as 3,000 taxpayers' leagues to protest high property taxes. These groups endorsed measures to limit and rollback taxes, lowered penalties on tax delinquents, and cuts in government spending. A few also called for illegal resistance (or tax strikes). The best known of these was led by the Association of Real Estate Taxpayers in Chicago which, at its height, had 30,000 dues-paying members.

An important intellectual movement, calling itself Southern Agrarians and based in Nashville, brought together like-minded novelists, poets and historians who argued that modern values undermined the traditions of American republicanism and civic virtue.

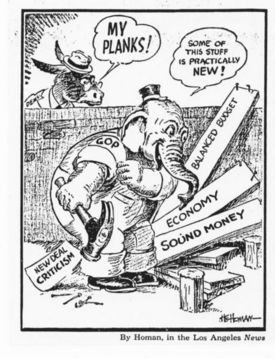

The Depression brought liberals to power under President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933). Indeed the term "liberal" now came to mean a supporter of the New Deal. In 1934 Al Smith and pro-business Democrats formed the American Liberty League to fight the new liberalism, but failed to stop Roosevelt's shifting the Democratic party to the left. In 1936 the Republicans rejected Hoover and tried the more liberal Alf Landon, who carried only Maine and Vermont. When Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937 the conservatives finally cooperated across party lines and defeated it with help from Vice President John Nance Garner. Roosevelt unsuccessfully tried to purge the conservative Democrats in the 1938 election. The conservatives in Congress then formed a bipartisan informal Conservative Coalition of Republicans and southern Democrats. It largely controlled Congress from 1937 to 1964. Its most prominent leaders were Senator Robert Taft, a Republican of Ohio, and Senator Richard Russell, Democrat of Georgia.

In the United States, the Old Right, also called the Old Guard, was a group of libertarian, free-market anti-interventionists, originally associated with Midwestern Republicans and Southern Democrats. The Republicans (but not the southern Democrats) were isolationists in 1939-41, (see America First), and later opposed NATO and U.S. military intervention in the Korean War.

Rebirth of conservatism

The immediate post-war years saw conservatism in American life reduced to a marginalized state of existence[3]. The Great Depression was widely considered to have been the result of conservative economic policies (laissez-faire market economics) of the 1920s while, in foreign affairs, conservatism was identified with an isolationism which was held to have contributed to America's under-preparedness for the war when it finally did come. For years thereafter, the twin shibboleths of "Great Depression" and "isolationism" stalked American conservatism[4].

In the political arena, the marginality of American conservatism found its expression in a long series of electoral reverses which left conservatives in the minority even within the Republican Party, their usual political vehicle at the time[5]. Ultimately, even that bastion of conservative strength which had so vexed Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Supreme Court, was transformed with the appointment of Earl Warren as Chief Justice in 1954.

Because conservatism's links with the immediate past had been so effectively broken, it became necessary to re-invent conservatism on the basis of post-Depression, post-war issues and concerns. Russell Kirk made an important initial contribution to this effort with his 1953 book The Conservative Mind wherein he laid out certain fundamental guiding principles of conservative thoiught and worldview:

- "Belief in a transcendent order, or body of natural law, which rules society as well as conscience."

- "Affection for the proliferating variety and mystery of human existence, as opposed to the narrowing uniformity, egalitarianism, and utilitarian aims of most radical systems;"

- "Conviction that civilised society requires orders and classes, as against the notion of a 'classless society'."

- "Persuasion that freedom and property are closely linked: separate property from private possession, and the Leviathan becomes master of all."

- "Faith in prescription and distrust of 'sophisters, calculators, and economists' who would reconstruct society upon abstract designs."

- "Recognition that change may not be salutary reform: hasty innovation may be a devouring conflagration, rather than a torch of progress."

Soon thereafter, the National Review magazine was started, giving conservatives a periodical voice.

Throughout the immediate post-war years, a number of severe political shocks were delivered to the American body politic which conservatives were able to exploit to reinvigorate their movement.

In the late 1940s, the communists under Mao Tse-Tung came to power in China and about the same time, the USSR demonstrated its nuclear capability by exploding an atomic bomb. Many Americans could not understand how these events could have happened and their confusion and fears were only enhanced by charges that forces and people unfriendly to America were at work internally, including in the U.S. State Department, to aid and abet the communist forces. The Hiss case and the sensational charges of Joseph McCarthy brought the issue of internal subversion to the forefront.

Soon thereafter, the United States found itself in a stalemate military situation on the Korean peninsula which many conservatives felt was due to political interference, or worse, which was hampering the conduct of the war and hamstringing U.S. troops. When news came of a number of American POWs who had begun to cooperate with the communist enemy, it appeared to these same conservatives that the American educational system was dangerously flawed in that, accoring to them, it did not provide American students with an adequate understanding of the "principles, rights, and political forms they were supposed to defend in the Korean War" (Russell Kirk, The American Cause)[6].

This was the first serious salvo aimed at what had, until then, been an American consensus on public education. In 1963, Max Rafferty, the elected California State Superintendent of Public Instruction, puclished Suffer, Little Children, continuing the conservative critique of public education. Also about that same time, Milton Friedman, in Capitalism and Freedom, put forth his proposal for school vouchers, an idea eventually validated as to its constitutionality by the U.S. Supreme Court. Joined in the 1960s by left/liberal critics such as John Holt, by the end of that decade, the American consensus on education had been shattered, though there still remained the formidable task of constructing institutional and other alternatives.

Another significant element entered the equation of the conservative revival in the mid-1950s with the publication of Atlas Shrugged, a novel by Ayn Rand extolling the virtues of a libertarian society and economic system. Her writings proved to be immensely popular with large numbers of young college students and form the basis of a libertarian tradition.

The conservative movement continued to gain strength, soon enough coalescing around a prominent national spokesperson in Barry Goldwater. Goldwater's book, The Conscience of a Conservative, outlined a political and ideological agenda for the conservative movement. Then, in 1964, after a bruising primary fight with a succession of opponents (Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, Nelson Rockefeller of New York, and William J. Scranton of Pennsylvania) identified by conservatives as representaives of the eastern establishment, Goldwater finally emerged victorious at the Republican National Convention in San Francisco and the conservatives, after many years, had a candidate whom they felt they could unequivacally support.

The success of the Civil Rights movement came in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Most conservatives supported both, but Barry Goldwater opposed them. Until then southern whites (both liberal and conservative) had been locked into the Democratic party. That lock was now broken and southern conservatives started voting for Republican candidates for president in 1964-68, and by the 1990s they were also voting for GOP candidates for state and local office. The southern blacks now began to vote in large numbers, and they became Democrats, moving that party in the south to the left.

Goldwater, a charismatic figure whose intense opposition to New Deal and Great Society programs angered many liberals and conservatives, was defeated in a landslide in 1964. His supporters regrouped under new leadership, especially that of Ronald Reagan in California, and regained strength in the 1966 elections. Conservatives voted for Richard Nixon in 1968, who narrowly defeated the Great Society champion Hubert Humphrey, and southern demagogue George Wallace. Nixon had come to terms with both the Goldwater wing of the party and the still-influential Rockefeller Republicans (Republicans from the Northeast who supported many New Deal programs).

References

- ↑ , 18. Judicial Review, Thomas Jefferson on Politics & Government, University of Virginia

- ↑ Curtis, Bruce. "William Graham Sumner 'On the Concentration of Wealth.'" Journal of American History 1969 55(4): 823-832.

- ↑ This can best be summarized by a statement of Lionel Trilling's contained in his 1950 book, The Liberal Imagination: Essays on Literature and Society: "In the United States at this time, liberalism is not only the dominant, but even the sole intellectual tradition. For it is the plain fact that nowadays, there are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circulation" adding that the "conservative impulse . . . expresses itself not in "ideas but only in action or in irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas".

- ↑ One popular bumper sticker which was seen during Barry Goldwater's presidential campaign of 1964 read: "Goldwater in '64; Hot water in '65; Cold water in '66" reflecting fears that a Goldwater victory would spell a return to the Depression years.

- ↑ At that time, the conservatives were politically unable to implement a program of their own. Instead, they were in a position of being able only to conduct rear-guard actions on selected issues in conjunction with southern Democrats, relying in part on the latter's control of key Senate and House committeee chairmanships and the filibuster rules which, at the time, required a 2/3 majority to shut off debate.

- ↑ So as to drive home this point, later in that same book, Kirk states in support of this contention: "a subcommittee of the Senate concluded that the failure of our educational system to provide proper instruction in history, politics, economics, and other subjects was a principal cause of the bewildered and shameful conduct of the majority of American prisoners."