Aristotle: Difference between revisions

imported>Peter J. King (→External links: rm incorrect cat.) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (119 intermediate revisions by 29 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | |||

{{ | {{TOC|right}} | ||

{{Image|Bust of Aristotle.jpg|left|350px|A marble bust of Aristotle.}} | |||

| | '''Aristotle''' (Ancient [[Greek]]: ''Ἀριστοτέλης, Aristotélēs''), a Greek [[Philosopher|philosopher]] of the fourth century BCE, was born just in time to know [[Plato]], another influential philosopher, and worked on many diverse subjects with unusual taxonomical zeal. | ||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

}} | |||

'''Aristotle''' ([[ | |||

Aristotle was particularly interested in observing nature and his writings on biology were much admired by [[Charles Darwin]] amongst others. Throughout the Middle Ages, no other thinker had as great an influence as Aristotle, and he merited in the thirteenth century alone some five separate Papal bans. Today, Aristotle's legacy remains in many fields of endeavour and he is usually considered one of the great foundational figures of both philosophy and natural science. | |||

Aristotle | ==Early years== | ||

{{Image|ClassicalGreece.gif|left|350px|Greece at the time of Aristotle (Chalcidic Peninsula lays between Thrace and Macedonia at the north-west edge of the Aegean Sea.) Source: U.S.M.A.}} | |||

Born in 384 BCE in Stagirus (alternately Stagira or Stageirus), a small town in northern Greece on the Chalcidic Peninsula, to Nicomachus, a medical doctor, and Phaestis, his mother, Aristotle’s family was probably native to that area. | |||

Traditionally a son followed his father’s profession or trade. However, Nicomachus died when Aristotle was a boy. Prior to that death, there is reason to believe that his father’s influence was significant. At the time, patients did not got to doctors, doctors went their patients. It is not unreasonable to think Aristotle accompanied his father on his travels. | |||

Nicomachus found work more to his preferences in the neighboring state of Macedonia and he was eventually appointed personal physician to Amyntas III, the king of Macedonia, in the capitol, Pella. This was the King Amyntas whose son Philip successfully united a number of the Greek city states after defending Macedonia, and he in turn was the father of Alexander, The Great. Aristotle was almost the exact age as Philip and it is likely that they were acquainted if not actually friends. Later in life Philip was to support some of Aristotle’s ambitions, if only for a time, indicating that they agreed on some things and enjoyed some measure of trust. | |||

Nicomachus died about the time Aristotle was 10 years old. As a consequence he did not become a physician. Although it is not absolutely clear from the evidence we have, it would also seem that his mother Phaestis, died while Aristotle was young | |||

Aristotle’s future was then in the hands of a guardian, Proxenus of Atarneus, who might have been an uncle or a family friend. Proxenus was a teacher of Greek, rhetoric, and poetry, which presumably would have rounded out the teaching in biological topics Aristotle had received from his father. Aristotle’s prose written later in life was of such quality that it seems reasonable to think he was also taught this subject when he was young.<ref name=KingPembrokeLife>[http://users.ox.ac.uk/~worc0337/authors/aristotle.html Aristotle Life and Work] King, Peter J., Pembroke College, Oxford University</ref><ref name=MacTutorAristotle>[http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Aristotle.html Aristotle Biography] O'Connor, John J. and Robertson, Edmund F. (1999). ''MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive'', School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland</ref> | |||

=== | ===Plato's Academy=== | ||

In | In 367, at the age of 17, he was sent to [[Athens]] where he entered Plato’s Academy and remained there for twenty years. It is not clear why Aristotle went to Athens; perhaps he had read Plato’s dialogues while in Stagira and wanted to study with him in particular or maybe Athens was simply the place to study at the time. During those twenty years, Aristotle was not simply a pupil; he carried out independent studies in natural science, and led lectures especially on the subject of rhetoric. [[Plato]] died in 347 and leadership of the Academy was passed on to his nephew Speusippus, who best represented the teachings of Plato. While Plato lived, Aristotle was a loyal member of the Academy; however even then, Aristotle’s thoughts on important points began to diverge from Platonism. Perhaps due to his growing dissatisfaction with the curriculum of the Academy or to anti-Macedonian feeling at Athens due to political unrest, Aristotle accepted an invitation from Hermeias, a former fellow-student in the Academy turned ruler of Atarneus and Assos, on the coast of Asia minor. | ||

===Years at Atarneus=== | |||

He remained in Atarneus for three years and married Pythias, niece of Hermeias, who bore him a daughter of the same name. After the death of his first wife, his second wife Herpyllis, a native to Stagira, bore him a son, Nicomachus, after whom the ''[[Nicomachean Ethics]]'' were named. At the end of three years, Aristotle moved to Mitylene, a neighboring island of Lesbos. Aristotle’s works suggest that he devoted part of his time in the Aegean to the study of marine biology. | |||

In | ===Relocating to Pella=== | ||

In 343, Philip of Macedon, in succession to his father Amyntas, invited Aristotle to undertake the education of his thirteen year old son, Alexander, who later would become [[Alexander the Great]]. Little to nothing is known about the education of Alexander but it is probably during this time that Aristotle turned his attention to political subjects. In 340, Alexander was appointed regent for his father and his pupillage ended. Subsequently, Aristotle may have settled in Stagira. | |||

Aristotle | ===Death of Philip and Establishing the Lyceum=== | ||

In 335, soon after Philip’s assassination, Aristotle returned to Athens and though the Academy flourished under new leadership, he preferred to set up his own school called the [[Lyceum (Aristotle)|Lyceum]]. Every morning at the Lyceum, Aristotle and his students discussed the more abstruse philosophical matters such as logic, physics and metaphysics and in the afternoon and evenings held lectures/discussions in more popular matters such as rhetoric and politics. Shortly after the death of Alexander the Great in 323, anti-Macedonian feelings swept over Athens and Aristotle, once again, left Athens and retired to Chalcis, where his mother’s family had estates. Soon after, in 322, he died.<ref>Ross, D. ''Aristotle''. Routledge Press, 2004. 336 pp.</ref><ref>Barnes, J. ''The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle''. Cambridge University Press, 1995. 404 pp.</ref> | |||

== | ==The works of Aristotle== | ||

''Please refer to this page’s catalog for a complete list of Aristotle’s works, and to the subpage on the [[spurious works of Aristotle]].'' | |||

Though much of Aristotle’s thought is historically interesting, it is also fascinating because it is a comprehensive picture of the world that differs, in some ways dramatically, from that of modern people. The works of Aristotle, however, can be daunting to the uninitiated. | |||

Unlike the carefully presented and highly literary works of Plato, the works of Aristotle tend to be terse and pithy, and to an extreme extent. In fact, the works of Aristotle which survive to the present day seem to be something like lecture notes.<ref>p. 3, Barnes | |||

</ref> | |||

In addition to the prose style of Aristotle’s extant works, his texts are also made difficult by their frequently piecemeal nature. A comparison with Plato is again useful. Plato’s works are made to be read by an individual reader, and are generally self-contained. Aristotle’s works, as lecture notes, refer only briefly to important concepts that are not strictly relevant to the subject at hand. For example, much of his work is underlain by his conviction that particulars are [[ontology|ontologically]] prior to [[universals]], but this idea is only explained at length in a couple of places. It’s worth observing that Aristotle, as a lecturer, would have been able to leave the topic at hand and explain any important ideas his listeners were unfamiliar with. | |||

Aristotle | It is also important not to underestimate the difficulties that Aristotle’s language creates. Aristotle wrote in Ancient Greek, but it is not a Greek which translates easily to normal-sounding English. Aristotle makes liberal use of technical terms. For example, ‘form’ and ‘knowledge’ in English are each the best translation for three separate Greek words which Aristotle uses with different shades of meaning. He does not, however, use these terms consistently. | ||

The style and organization of his works are not always negatives. Aristotle is made easier reading by the fact that his works frequently follow a predictable form. He often begins one of his investigations by stating the conclusions of earlier thinkers: frequently Plato, but other thinkers as well. <ref>This is connected with his valuation of ‘reasonable opinions.’ Cf. the discussion at Barnes, 15ff.</ref> Then, he moves to a consideration of the problems, or aporiai, with a given idea, and he finally states his opinion-- before moving to a discussion of the problems with his opinion! (It can be helpful for the reader to highlight, underline, or otherwise mark the proposition Aristotle is espousing.) | |||

Aristotle | |||

== | ==Ideas, method and achievements <ref>'A large part of an early version of this section was taken from the entry on Aristotle in 'Essentials of Philosophy and Ethics', edited by Martin Cohen, (Hodder Arnold 2006) and donated to the Citizendium by the author.'' </ref>== | ||

Neither Aristotle nor the other Greek philosophers made any distinction between scientific and philosophical investigations. Aristotle was particularly interested in observing nature and his biology was much admired by [[Darwin]] amongst others. Aristotle influenced subsequent studies by his view that organisms had a function, were striving towards some purposeful end, and that nature is not haphazard. If plant shoots are observed to bend towards the light they are ‘seeking the light’. The function of mankind is, he suggests, to reason, as this is what people are better at than any other member of the animal kingdom - ‘Man is a rational animal’. This approach is in contrast to that of today's biologist or scientist who try to explain things by reference to ‘mechanisms’. | |||

=== | ===Political ideas=== | ||

Aristotle | Aristotle marks the watershed in Greek philosophy, born fifteen years after the execution of [[Socrates]] in 399 B.C.E, studying at the Academy in Athens under [[Plato]] until B.C.E 347. Although he had hoped to become Plato's successor, in fact Aristotle's approach was was out of favour with the mathematicians of the time, and Plato's nephew, Speussippus took over instead. After this Aristotle left Greece for Asia Minor where for the next five years he concentrated on developing his philosophy and biology. He then returned to Macedonia to be tutor to the future Alexander the Great, but there is little evidence of him influencing his pupil and indeed Aristotle seems to have been largely oblivious to the social and geo-political changes that were already making his approach to politics largely irrelevant. | ||

Indeed, even whilst Aristotle was teaching about the ''polis'' in the Lyceum, Alexander was already planning an empire in which he would rule the whole of Greece and Persia, in the process producing a new society in which both Greeks and barbarians would become, as [[Plutarch]] later put it, ‘one flock on a common pasture’ feeding under one law. In fact, whilst Aristotle wrote on the case of the 'polis', for almost two millennia the area was to see no city states, but instead a succession of empires. The rule of Macedonia, of Rome, and of Charlemagne came and went, with Aristotle not even so much as a footnote. Yet for much of this time, Aristotle was widely studied in the Islamic world, where he was hailed as 'the wise man' and his texts were carefully preserved. In the Middle Ages his ideas were 'rediscovered' by St Thomas Aquinas and, especially given the effective marriage of the Catholic Church with the state, became highly influential. | |||

Aristotle was similarly concerned at the fractious nature of the Greek city states in his time, the fourth century B.C.E. The states were small, but that did not stop them continually splitting into factions that fought amongst themselves. A whole book of Aristotle’s political theory is devoted to this problem. And Aristotle shared Plato's aversion to tyranny, warning that under such government, all citizens would be constantly on view, and a secret police ‘like the female spies employed at Syracuse, or the eavesdroppers sent by the tyrant Hiero to all social gatherings’ would be employed to sow fear and distrust. For these are the essential and characteristic hallmarks of tyrants. | |||

Aristotle sees the origin of the state differently from Plato, stating explicitly that ‘a State is not a sharing of a locality for the purpose of preventing mutual harm and promoting trade.’ True to his being a keen biologist first, a metaphysician second, he believed the state should be understood as an organism with a purpose, in this case, to promote happiness, or eudaimonia. Of course, this is only a particular type of happiness, quintessentially that of philosophical contemplation, that the Greeks - or at least the philosophers! - valued most. But in this basic assumption, Aristotle’s theory of human society is actually fundamentally different from Socrates and Plato’s. | |||

For Aristotle, society is a means to ensure that the social nature of people - in forming families, in forming friendships and equally in trying to rule and control others, is channelled away from the negative attributes of human beings - greed and cruelty - towards the positive aspects - love of truth and knowledge - those of what he classed misleadingly as ‘the rational animal’. Misleading, because, after all, any animal is rational to the extent that it takes decisions to obtain food or to preserve its life. (The Chinese sages instead defined humans as ‘moral animals’.) Certainly, rationality pursued as a philosophical venture remained only available to an aristocratic leisured few. | |||

In other ways, too, Aristotle’s Politics strike a discordant note. He defined the state as a collection of a certain size of citizens participating in the judicial and political processes of the City. But the term ‘citizens’ was not to include many inhabitants of the city. He did not include slaves, nor (unlike Plato) women, nor yet those who worked for a living. ‘For some men,’ Aristotle wrote, ‘belong by nature to others’ and so should properly be either slaves or chattels. | |||

For Aristotle, liberty is fundamental for citizens - but it is a peculiar kind of liberty even for these privileged members of society. The state reserves the right to ensure efficient use of property, for its own advantage, and Aristotle agrees with Plato, that the production of children should be controlled to ensure the new citizens have ‘the best physique’. ( In Plato, it is put more generally so as to ‘improve on nature’. ) And, again like Plato, naturally, they will have to be educated in the manner determined by the state. ‘Public matters should be publicly managed; and we should not think that each of the citizens belongs to himself, but that they all belong to the State.’ Aristotle even produces a long list of ways in which the lives of citizens should be controlled. For the state is like the father in a well-regulated household: the children, (the citizens) ‘start with a natural affection and disposition to obey.’ | |||

===The Laws of Thought=== | |||

Aristotle’s greatest achievement is generally supposed to have been his Laws of Thought - part of his attempt to put everyday language on a logical footing. Like many contemporary philosophers he regarded logic as providing the key to philosophical progress. The traditional ‘laws of thought’ are that: | |||

• whatever is, is (the law of identity); | |||

• nothing can both be and not be (the law of non-contradiction); and | |||

• everything must either be or not be (the law of excluded middle). | |||

His ''Prior Analytics'' is the first attempt o create a system of formal deductive logic. | |||

===Science=== | |||

{|align="right" cellpadding="10" style="background:lightgray; width:35%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-size: 93%; font-family: Gill Sans MT;" | |||

| A science, according to Aristotle, can be set out as an axiomatic system in which necessary first principles lead by inexorable inferences to all of the truths about the subject matter of the science...Scientific knowledge is therefore demonstrative; what we know scientifically is what we can derive, directly or indirectly, from first principles that do not themselves require proof...What, then, is the status of the first principles? They clearly cannot be known in the same way as the consequences derived from them, i.e., demonstratively, yet Aristotle is confident that they must be known—for how could knowledge be derived from what is not knowledge? They are, Aristotle tells us, grasped by the mind (Aristotle's term is ''nous'', usually translated as intuition or understanding). This way of putting the matter makes it seem as if an Aristotelian science is an entirely a priori enterprise in which reason alone grasps first principles and logic takes over from there to arrive at all of the truths of science...Aristotle does not think that this alone is the way a scientist goes about acquiring his knowledge, for in his own scientific treatises, he does not begin by announcing the first principles and deducing their consequences. Rather, he sets out the puzzles the science is trying to solve and the observations that have been made and the opinions that have been held about them. Perhaps he thinks of the axiomatic presentation as a kind of ideal that is possible only for a completed science and is appropriate for teaching it rather than for making discoveries in it. As for the acquisition of first principles, Aristotle appeals to what sounds somewhat like an inductive procedure. Beginning with the perception of particulars, which are "better known to us,' and moving through memory and experience, we arrive at knowledge of universals, which are "better known in themselves"...Aristotle's approach thus seems to combine features of both rationalism and empiricism. | |||

: — Cohen SM, Curd P, Reeve CDC<ref name=cohen2011> Cohen SM, Curd P, Reeve CDC. (2011) ''Readings in Ancient Greek Philosophy: From Thales to Aristotle''. Fourth Edition. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, ISBN 9781603844635; ISBN 9781603844628; Adobe PDF ebook ISBN 9781603845977. </ref> | |||

|} | |||

The ''Posterior Analytics'' attempts to use this to systematise scientific knowledge. In fact, about a quarter of Aristotle's writing seems to have been concerned with categorising nature, in particular animals. He describes the nature of space and time, and the different forms soul takes in different creatures. Some of his observations (such as that of how dolphins gave birth to their young) were careful and original, but equally certainly Aristotle has his fair share of foolish views, such as the influential but false doctrine that bodies fall to earth at speeds proportional to their mass, or the uninfluential but foolish claim that women had less teeth than men. | |||

Aristotle | |||

Aristotle has | |||

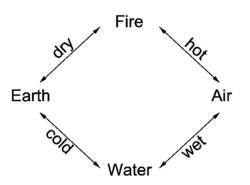

{{Image|Classical elements.png|left|250px|Fig. 1 The four Aristotelian elements and their interconversion}} | |||

Following [[Empedocles]], Aristotle distinguishes four sub-lunar elements each with two basic properties (''qualitates symbolae'') | |||

<div align = "center"> | |||

<table width="30%"> | |||

<tr> <td> <b>Earth</b> <td> dry <td> cold | |||

<tr> <td> <b>Water</b> <td> <td> cold <td> wet | |||

<tr> <td> <b>Air </b> <td> <td> <td> wet <td> hot | |||

<tr> <td> <b>Fire </b> <td> <td> <td> <td> hot <td> dry | |||

</tr></table> | |||

</div> | |||

He claims that all homogeneous materials are compounds of these four elements. All elements can be converted into each other, but most preferably the conversion is to an element that shares one of the four basic properties (dry, wet, cold, hot) with the element to be converted, see Fig. 1. To the four earthly element Aristotle added a fifth heavenly element, the [[ether (physics)|Aether]]. | |||

== | ===Ethics=== | ||

'' | Aristotle's views on morality are set out in the ''Nicomachean'' and the ''Eudaemian'' Ethics. The ''Nicomachean Ethics'' is one of the most influential books of moral philosophy, including accounts of what the Greeks considered to be the great virtues, and Aristotle’s great souled man, who speaks with a deep voice and level utterance, and who is not unduly modest either, as well as reminding us wisely that “without friends, no one would choose to live, though he had all other goods”. The main idea in Aristotle's ethics is that the proper end of mankind is the pursuit of ''eudaimonia'' which is Greek for a very particular kind of ‘happiness’. ''Eudaimonia'' has three aspects: as well as mere pleasure, there is political honour,, and the rewards of contemplation. Quintessentially, of course, as philosophy. | ||

Other doctrines often attributed to Aristotle, notably the merit of fulfilling your ‘function’, of cultivating the ‘virtues’, (hence, 'virtue ethics') and of the ‘golden mean’ between two undesirable extremes are, of course, all much older. Indeed Plato puts the ideas forward much more cogently. | |||

Nonetheless, one important difference between Aristotle and Plato is there in the ''Nicomachean Ethics'', where Aristotle starts with a survey of popular opinions on the subject of 'right and wrong', to find out how the terms are used, in the manner of a social; anthropologist. Plato makes very clear his contempt for such an approach. [[Thomas Hobbes]] said that it was this method that had led Aristotle astray, as by seeking to ground ethics in the 'appetites of men', he had chosen a measure by which (for Hobbes) correctly there is no law and no distinction between right and wrong. In fact, Hobbes considered Aristotle a great fool, protesting repeatedly the 'folly' of 'the Ancients. | |||

== | ==Influence== | ||

Aristotle represented an advanced paradigm at the time of his work. His epistemology contradicted his teacher Plato in a crucial manner. Both valued and emphasised reason and its use but Plato insisted that the most important truths, the objects of knowledge, must be attained through reason alone, | |||

Aristotle on the other hand, emphasised observation, holding that the world and the mind were compatible in that understanding was possible. This may have been articulated as such earlier by someone else, but prior to Aristotle, there was a history of observation by the pre-socratic philosophers to substantiate understanding.<ref>[http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/History_of_astronomy#Pre-socratic_Astronomy Internal CZ Link to History of Astronomy]</ref> While this may seem trivial, even self evident now, this was a paramount step toward the development of science and it is a crucial aspect of any field in science, that we believe that we can know. And for Aristotle that knowing was achieved through observing. | |||

Most of Aristotle’s observations have been lost. His world was the world of Philip of Macedon and Alexander the Great. His association with the royal Macedonian house made it necessary to move around a great deal. In the years that followed his death, most of his works were lost and much of what remains are compilations made centuries later, collections of notes and original works. As the centuries continued, translations were made and then translations of those translations. In the end very little of his original work remains now, more than 2,300 years later | |||

So, while his observations and his deductions for those observations were very important in the development of science that was to come later, it is fragmented and what remains is full of errors. He did however bestow the early seeds of systematic investigation into natural phenomena and to that extent can be credited at least as a midwife at the birth of empirical science if not actually the founder. It is a tragic irony that his observations and opinions were to stifle the very thing he pursued for so many years. | |||

Aristotle treated knowledge as common property, not to be held in secret. He worked in the company of others and readily spoke and wrote of this thoughts. His attitude in this prefigures one of the foundations of modern science in that he believed that one could not claim to know a subject unless capable and willing to transmit that knowledge to others. This attitude of openness was often lacking in some of the greatest thinkers of the 15th through the 17th century and was to cause no end of grief. Even up to this day the actual credit for some of the primary advances in science are still being debated due to a lack of cooperation and openness practiced by Artistotle nearly 2,000 years earlier. | |||

Another of his contributions, Aristotle also made the divisions in knowledge we have today, theology and physics and math, language, ethics and politics are all distinct separate fields. This too would have far reaching implications. | |||

One of the most enduring works on the subject of cosmology was his ''On the heavens'' written about 350 BCE Until it was seriously challenged in the early 16th century by [[Copernicus]], amongst others, it was the considered authority on [[Cosmology|cosmology]]. He posited the nature of substance, the nature and manner of movement, the nature of the heavens and its eternal existence. | |||

How much of what we have that is attributed to him is in fact what he said or wrote--regardless of whether he was the originator or he learned form others--or was simply added to his writings after his death is debatable. One of the standard works on Aristotle was that of W. W. Jaeger (1888-1961). His interpretations of Aristotles works included his opinions about what was added later. Jeager's summations in the classic ''Artistotle'' (1948) still receive critical analysis | |||

<ref>[http://phyun5.ucr.edu/~wudka/Physics7/Notes_www/node35.html Aristotelian Cosmology] Wudka, Jose (1998) ''Relativity and Cosmology'', Physics Dept. University of California, Riverside; [http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/heavens.mb.txt On the Heavens] Stock, J.L (trans); [http://users.ox.ac.uk/~worc0337/authors/aristotle.html Aristotle Life and Work] King, Peter J., Pembroke College, Oxford University; [http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Aristotle.html Aristotle Biography] O'Connor, John J. and Robertson, Edmund F. (1999). ''MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive'', School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland; William M. Calder III (ed.), ''Werner Jaeger Reconsidered''. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992. Illinois Classical Studies; [http://classics.mit.edu//Aristotle/metaphysics.1.i.html Translated by W. D. Ross] Internet Classics Archive, Massachusetts Institute of Technology</ref> | |||

== | ===Contemporary Aristotelians=== | ||

Despite that during the early modern period Aristotle's ideas fell out of fashion due to the emergence of a new paradigm based on [[Descartes]], [[Locke]], and [[Kant]], many contemporary scholars have sought to revive Aristotle's legacy in many fields. In ethics and politics, [[Ayn Rand]], [[Philippa Foot]], and [[Alasdair MacIntyre]] are among these thinkers. | |||

== | ==Criticism of Aristotle== | ||

Aristotle is generally counted as one of the 'great philosophers'. However, during his lifetime and for many years afterwards, his reputation was rather less golden. Indeed, the renowned 'sceptic', Timon of Philus, sneered at "the sad chattering of the empty Aristotle" while Theocritus of Chios wrote a rather unkind epigram on him which runs: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

The empty-headed Aristotle rais'd | |||

This empty tomb to Hermias the Eunuch, | |||

The ancient slave of the ill-us'd Eubulus. | |||

(Who for his monstrous appetite, preferred | |||

The Bosphorus to Academia's groves.) | |||

</blockquote> | |||

In the Nineteenth Century, the scientist, John Tyndall, complained that Aristotle's statements were most accepted when they were most incorrect, whilst in the Twentieth, Karl Popper accused Aristotle of having held up the development of thought itself. <ref> Philosophical Tales, by Martin Cohen, Blackwell 2008 p14 </ref> | |||

<blockquote> | |||

The development of thought since Aristotle, could, I think, be summed up by saying that every discipline, as long as it used the Aristotelian method of definition, has remained arrested in a state of empty verbiage and barren scholasticism, and that the degree to which the various sciences have been able to make any progress depended on the degree to which they have been able to get rid of this essentialist method. (This is why so much of our "social science" still belongs to the Middle Ages).<ref> K. R. Popper, ''The open society and its enemies. Vol. 2. Hegel and Marx.'' | |||

London: Routledge, (1945). p. 9 </ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

===Notes=== | |||

{{reflist|2}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

[[Category: | |||

Latest revision as of 16:00, 12 July 2024

Aristotle (Ancient Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης, Aristotélēs), a Greek philosopher of the fourth century BCE, was born just in time to know Plato, another influential philosopher, and worked on many diverse subjects with unusual taxonomical zeal.

Aristotle was particularly interested in observing nature and his writings on biology were much admired by Charles Darwin amongst others. Throughout the Middle Ages, no other thinker had as great an influence as Aristotle, and he merited in the thirteenth century alone some five separate Papal bans. Today, Aristotle's legacy remains in many fields of endeavour and he is usually considered one of the great foundational figures of both philosophy and natural science.

Early years

Born in 384 BCE in Stagirus (alternately Stagira or Stageirus), a small town in northern Greece on the Chalcidic Peninsula, to Nicomachus, a medical doctor, and Phaestis, his mother, Aristotle’s family was probably native to that area.

Traditionally a son followed his father’s profession or trade. However, Nicomachus died when Aristotle was a boy. Prior to that death, there is reason to believe that his father’s influence was significant. At the time, patients did not got to doctors, doctors went their patients. It is not unreasonable to think Aristotle accompanied his father on his travels.

Nicomachus found work more to his preferences in the neighboring state of Macedonia and he was eventually appointed personal physician to Amyntas III, the king of Macedonia, in the capitol, Pella. This was the King Amyntas whose son Philip successfully united a number of the Greek city states after defending Macedonia, and he in turn was the father of Alexander, The Great. Aristotle was almost the exact age as Philip and it is likely that they were acquainted if not actually friends. Later in life Philip was to support some of Aristotle’s ambitions, if only for a time, indicating that they agreed on some things and enjoyed some measure of trust.

Nicomachus died about the time Aristotle was 10 years old. As a consequence he did not become a physician. Although it is not absolutely clear from the evidence we have, it would also seem that his mother Phaestis, died while Aristotle was young

Aristotle’s future was then in the hands of a guardian, Proxenus of Atarneus, who might have been an uncle or a family friend. Proxenus was a teacher of Greek, rhetoric, and poetry, which presumably would have rounded out the teaching in biological topics Aristotle had received from his father. Aristotle’s prose written later in life was of such quality that it seems reasonable to think he was also taught this subject when he was young.[1][2]

Plato's Academy

In 367, at the age of 17, he was sent to Athens where he entered Plato’s Academy and remained there for twenty years. It is not clear why Aristotle went to Athens; perhaps he had read Plato’s dialogues while in Stagira and wanted to study with him in particular or maybe Athens was simply the place to study at the time. During those twenty years, Aristotle was not simply a pupil; he carried out independent studies in natural science, and led lectures especially on the subject of rhetoric. Plato died in 347 and leadership of the Academy was passed on to his nephew Speusippus, who best represented the teachings of Plato. While Plato lived, Aristotle was a loyal member of the Academy; however even then, Aristotle’s thoughts on important points began to diverge from Platonism. Perhaps due to his growing dissatisfaction with the curriculum of the Academy or to anti-Macedonian feeling at Athens due to political unrest, Aristotle accepted an invitation from Hermeias, a former fellow-student in the Academy turned ruler of Atarneus and Assos, on the coast of Asia minor.

Years at Atarneus

He remained in Atarneus for three years and married Pythias, niece of Hermeias, who bore him a daughter of the same name. After the death of his first wife, his second wife Herpyllis, a native to Stagira, bore him a son, Nicomachus, after whom the Nicomachean Ethics were named. At the end of three years, Aristotle moved to Mitylene, a neighboring island of Lesbos. Aristotle’s works suggest that he devoted part of his time in the Aegean to the study of marine biology.

Relocating to Pella

In 343, Philip of Macedon, in succession to his father Amyntas, invited Aristotle to undertake the education of his thirteen year old son, Alexander, who later would become Alexander the Great. Little to nothing is known about the education of Alexander but it is probably during this time that Aristotle turned his attention to political subjects. In 340, Alexander was appointed regent for his father and his pupillage ended. Subsequently, Aristotle may have settled in Stagira.

Death of Philip and Establishing the Lyceum

In 335, soon after Philip’s assassination, Aristotle returned to Athens and though the Academy flourished under new leadership, he preferred to set up his own school called the Lyceum. Every morning at the Lyceum, Aristotle and his students discussed the more abstruse philosophical matters such as logic, physics and metaphysics and in the afternoon and evenings held lectures/discussions in more popular matters such as rhetoric and politics. Shortly after the death of Alexander the Great in 323, anti-Macedonian feelings swept over Athens and Aristotle, once again, left Athens and retired to Chalcis, where his mother’s family had estates. Soon after, in 322, he died.[3][4]

The works of Aristotle

Please refer to this page’s catalog for a complete list of Aristotle’s works, and to the subpage on the spurious works of Aristotle.

Though much of Aristotle’s thought is historically interesting, it is also fascinating because it is a comprehensive picture of the world that differs, in some ways dramatically, from that of modern people. The works of Aristotle, however, can be daunting to the uninitiated.

Unlike the carefully presented and highly literary works of Plato, the works of Aristotle tend to be terse and pithy, and to an extreme extent. In fact, the works of Aristotle which survive to the present day seem to be something like lecture notes.[5] In addition to the prose style of Aristotle’s extant works, his texts are also made difficult by their frequently piecemeal nature. A comparison with Plato is again useful. Plato’s works are made to be read by an individual reader, and are generally self-contained. Aristotle’s works, as lecture notes, refer only briefly to important concepts that are not strictly relevant to the subject at hand. For example, much of his work is underlain by his conviction that particulars are ontologically prior to universals, but this idea is only explained at length in a couple of places. It’s worth observing that Aristotle, as a lecturer, would have been able to leave the topic at hand and explain any important ideas his listeners were unfamiliar with.

It is also important not to underestimate the difficulties that Aristotle’s language creates. Aristotle wrote in Ancient Greek, but it is not a Greek which translates easily to normal-sounding English. Aristotle makes liberal use of technical terms. For example, ‘form’ and ‘knowledge’ in English are each the best translation for three separate Greek words which Aristotle uses with different shades of meaning. He does not, however, use these terms consistently.

The style and organization of his works are not always negatives. Aristotle is made easier reading by the fact that his works frequently follow a predictable form. He often begins one of his investigations by stating the conclusions of earlier thinkers: frequently Plato, but other thinkers as well. [6] Then, he moves to a consideration of the problems, or aporiai, with a given idea, and he finally states his opinion-- before moving to a discussion of the problems with his opinion! (It can be helpful for the reader to highlight, underline, or otherwise mark the proposition Aristotle is espousing.)

Ideas, method and achievements [7]

Neither Aristotle nor the other Greek philosophers made any distinction between scientific and philosophical investigations. Aristotle was particularly interested in observing nature and his biology was much admired by Darwin amongst others. Aristotle influenced subsequent studies by his view that organisms had a function, were striving towards some purposeful end, and that nature is not haphazard. If plant shoots are observed to bend towards the light they are ‘seeking the light’. The function of mankind is, he suggests, to reason, as this is what people are better at than any other member of the animal kingdom - ‘Man is a rational animal’. This approach is in contrast to that of today's biologist or scientist who try to explain things by reference to ‘mechanisms’.

Political ideas

Aristotle marks the watershed in Greek philosophy, born fifteen years after the execution of Socrates in 399 B.C.E, studying at the Academy in Athens under Plato until B.C.E 347. Although he had hoped to become Plato's successor, in fact Aristotle's approach was was out of favour with the mathematicians of the time, and Plato's nephew, Speussippus took over instead. After this Aristotle left Greece for Asia Minor where for the next five years he concentrated on developing his philosophy and biology. He then returned to Macedonia to be tutor to the future Alexander the Great, but there is little evidence of him influencing his pupil and indeed Aristotle seems to have been largely oblivious to the social and geo-political changes that were already making his approach to politics largely irrelevant.

Indeed, even whilst Aristotle was teaching about the polis in the Lyceum, Alexander was already planning an empire in which he would rule the whole of Greece and Persia, in the process producing a new society in which both Greeks and barbarians would become, as Plutarch later put it, ‘one flock on a common pasture’ feeding under one law. In fact, whilst Aristotle wrote on the case of the 'polis', for almost two millennia the area was to see no city states, but instead a succession of empires. The rule of Macedonia, of Rome, and of Charlemagne came and went, with Aristotle not even so much as a footnote. Yet for much of this time, Aristotle was widely studied in the Islamic world, where he was hailed as 'the wise man' and his texts were carefully preserved. In the Middle Ages his ideas were 'rediscovered' by St Thomas Aquinas and, especially given the effective marriage of the Catholic Church with the state, became highly influential.

Aristotle was similarly concerned at the fractious nature of the Greek city states in his time, the fourth century B.C.E. The states were small, but that did not stop them continually splitting into factions that fought amongst themselves. A whole book of Aristotle’s political theory is devoted to this problem. And Aristotle shared Plato's aversion to tyranny, warning that under such government, all citizens would be constantly on view, and a secret police ‘like the female spies employed at Syracuse, or the eavesdroppers sent by the tyrant Hiero to all social gatherings’ would be employed to sow fear and distrust. For these are the essential and characteristic hallmarks of tyrants.

Aristotle sees the origin of the state differently from Plato, stating explicitly that ‘a State is not a sharing of a locality for the purpose of preventing mutual harm and promoting trade.’ True to his being a keen biologist first, a metaphysician second, he believed the state should be understood as an organism with a purpose, in this case, to promote happiness, or eudaimonia. Of course, this is only a particular type of happiness, quintessentially that of philosophical contemplation, that the Greeks - or at least the philosophers! - valued most. But in this basic assumption, Aristotle’s theory of human society is actually fundamentally different from Socrates and Plato’s.

For Aristotle, society is a means to ensure that the social nature of people - in forming families, in forming friendships and equally in trying to rule and control others, is channelled away from the negative attributes of human beings - greed and cruelty - towards the positive aspects - love of truth and knowledge - those of what he classed misleadingly as ‘the rational animal’. Misleading, because, after all, any animal is rational to the extent that it takes decisions to obtain food or to preserve its life. (The Chinese sages instead defined humans as ‘moral animals’.) Certainly, rationality pursued as a philosophical venture remained only available to an aristocratic leisured few.

In other ways, too, Aristotle’s Politics strike a discordant note. He defined the state as a collection of a certain size of citizens participating in the judicial and political processes of the City. But the term ‘citizens’ was not to include many inhabitants of the city. He did not include slaves, nor (unlike Plato) women, nor yet those who worked for a living. ‘For some men,’ Aristotle wrote, ‘belong by nature to others’ and so should properly be either slaves or chattels.

For Aristotle, liberty is fundamental for citizens - but it is a peculiar kind of liberty even for these privileged members of society. The state reserves the right to ensure efficient use of property, for its own advantage, and Aristotle agrees with Plato, that the production of children should be controlled to ensure the new citizens have ‘the best physique’. ( In Plato, it is put more generally so as to ‘improve on nature’. ) And, again like Plato, naturally, they will have to be educated in the manner determined by the state. ‘Public matters should be publicly managed; and we should not think that each of the citizens belongs to himself, but that they all belong to the State.’ Aristotle even produces a long list of ways in which the lives of citizens should be controlled. For the state is like the father in a well-regulated household: the children, (the citizens) ‘start with a natural affection and disposition to obey.’

The Laws of Thought

Aristotle’s greatest achievement is generally supposed to have been his Laws of Thought - part of his attempt to put everyday language on a logical footing. Like many contemporary philosophers he regarded logic as providing the key to philosophical progress. The traditional ‘laws of thought’ are that:

• whatever is, is (the law of identity); • nothing can both be and not be (the law of non-contradiction); and • everything must either be or not be (the law of excluded middle).

His Prior Analytics is the first attempt o create a system of formal deductive logic.

Science

A science, according to Aristotle, can be set out as an axiomatic system in which necessary first principles lead by inexorable inferences to all of the truths about the subject matter of the science...Scientific knowledge is therefore demonstrative; what we know scientifically is what we can derive, directly or indirectly, from first principles that do not themselves require proof...What, then, is the status of the first principles? They clearly cannot be known in the same way as the consequences derived from them, i.e., demonstratively, yet Aristotle is confident that they must be known—for how could knowledge be derived from what is not knowledge? They are, Aristotle tells us, grasped by the mind (Aristotle's term is nous, usually translated as intuition or understanding). This way of putting the matter makes it seem as if an Aristotelian science is an entirely a priori enterprise in which reason alone grasps first principles and logic takes over from there to arrive at all of the truths of science...Aristotle does not think that this alone is the way a scientist goes about acquiring his knowledge, for in his own scientific treatises, he does not begin by announcing the first principles and deducing their consequences. Rather, he sets out the puzzles the science is trying to solve and the observations that have been made and the opinions that have been held about them. Perhaps he thinks of the axiomatic presentation as a kind of ideal that is possible only for a completed science and is appropriate for teaching it rather than for making discoveries in it. As for the acquisition of first principles, Aristotle appeals to what sounds somewhat like an inductive procedure. Beginning with the perception of particulars, which are "better known to us,' and moving through memory and experience, we arrive at knowledge of universals, which are "better known in themselves"...Aristotle's approach thus seems to combine features of both rationalism and empiricism.

|

The Posterior Analytics attempts to use this to systematise scientific knowledge. In fact, about a quarter of Aristotle's writing seems to have been concerned with categorising nature, in particular animals. He describes the nature of space and time, and the different forms soul takes in different creatures. Some of his observations (such as that of how dolphins gave birth to their young) were careful and original, but equally certainly Aristotle has his fair share of foolish views, such as the influential but false doctrine that bodies fall to earth at speeds proportional to their mass, or the uninfluential but foolish claim that women had less teeth than men.

Following Empedocles, Aristotle distinguishes four sub-lunar elements each with two basic properties (qualitates symbolae)

| Earth | dry | cold | |||

| Water | cold | wet | |||

| Air | wet | hot | |||

| Fire | hot | dry |

He claims that all homogeneous materials are compounds of these four elements. All elements can be converted into each other, but most preferably the conversion is to an element that shares one of the four basic properties (dry, wet, cold, hot) with the element to be converted, see Fig. 1. To the four earthly element Aristotle added a fifth heavenly element, the Aether.

Ethics

Aristotle's views on morality are set out in the Nicomachean and the Eudaemian Ethics. The Nicomachean Ethics is one of the most influential books of moral philosophy, including accounts of what the Greeks considered to be the great virtues, and Aristotle’s great souled man, who speaks with a deep voice and level utterance, and who is not unduly modest either, as well as reminding us wisely that “without friends, no one would choose to live, though he had all other goods”. The main idea in Aristotle's ethics is that the proper end of mankind is the pursuit of eudaimonia which is Greek for a very particular kind of ‘happiness’. Eudaimonia has three aspects: as well as mere pleasure, there is political honour,, and the rewards of contemplation. Quintessentially, of course, as philosophy.

Other doctrines often attributed to Aristotle, notably the merit of fulfilling your ‘function’, of cultivating the ‘virtues’, (hence, 'virtue ethics') and of the ‘golden mean’ between two undesirable extremes are, of course, all much older. Indeed Plato puts the ideas forward much more cogently.

Nonetheless, one important difference between Aristotle and Plato is there in the Nicomachean Ethics, where Aristotle starts with a survey of popular opinions on the subject of 'right and wrong', to find out how the terms are used, in the manner of a social; anthropologist. Plato makes very clear his contempt for such an approach. Thomas Hobbes said that it was this method that had led Aristotle astray, as by seeking to ground ethics in the 'appetites of men', he had chosen a measure by which (for Hobbes) correctly there is no law and no distinction between right and wrong. In fact, Hobbes considered Aristotle a great fool, protesting repeatedly the 'folly' of 'the Ancients.

Influence

Aristotle represented an advanced paradigm at the time of his work. His epistemology contradicted his teacher Plato in a crucial manner. Both valued and emphasised reason and its use but Plato insisted that the most important truths, the objects of knowledge, must be attained through reason alone,

Aristotle on the other hand, emphasised observation, holding that the world and the mind were compatible in that understanding was possible. This may have been articulated as such earlier by someone else, but prior to Aristotle, there was a history of observation by the pre-socratic philosophers to substantiate understanding.[9] While this may seem trivial, even self evident now, this was a paramount step toward the development of science and it is a crucial aspect of any field in science, that we believe that we can know. And for Aristotle that knowing was achieved through observing.

Most of Aristotle’s observations have been lost. His world was the world of Philip of Macedon and Alexander the Great. His association with the royal Macedonian house made it necessary to move around a great deal. In the years that followed his death, most of his works were lost and much of what remains are compilations made centuries later, collections of notes and original works. As the centuries continued, translations were made and then translations of those translations. In the end very little of his original work remains now, more than 2,300 years later

So, while his observations and his deductions for those observations were very important in the development of science that was to come later, it is fragmented and what remains is full of errors. He did however bestow the early seeds of systematic investigation into natural phenomena and to that extent can be credited at least as a midwife at the birth of empirical science if not actually the founder. It is a tragic irony that his observations and opinions were to stifle the very thing he pursued for so many years.

Aristotle treated knowledge as common property, not to be held in secret. He worked in the company of others and readily spoke and wrote of this thoughts. His attitude in this prefigures one of the foundations of modern science in that he believed that one could not claim to know a subject unless capable and willing to transmit that knowledge to others. This attitude of openness was often lacking in some of the greatest thinkers of the 15th through the 17th century and was to cause no end of grief. Even up to this day the actual credit for some of the primary advances in science are still being debated due to a lack of cooperation and openness practiced by Artistotle nearly 2,000 years earlier.

Another of his contributions, Aristotle also made the divisions in knowledge we have today, theology and physics and math, language, ethics and politics are all distinct separate fields. This too would have far reaching implications.

One of the most enduring works on the subject of cosmology was his On the heavens written about 350 BCE Until it was seriously challenged in the early 16th century by Copernicus, amongst others, it was the considered authority on cosmology. He posited the nature of substance, the nature and manner of movement, the nature of the heavens and its eternal existence.

How much of what we have that is attributed to him is in fact what he said or wrote--regardless of whether he was the originator or he learned form others--or was simply added to his writings after his death is debatable. One of the standard works on Aristotle was that of W. W. Jaeger (1888-1961). His interpretations of Aristotles works included his opinions about what was added later. Jeager's summations in the classic Artistotle (1948) still receive critical analysis

Contemporary Aristotelians

Despite that during the early modern period Aristotle's ideas fell out of fashion due to the emergence of a new paradigm based on Descartes, Locke, and Kant, many contemporary scholars have sought to revive Aristotle's legacy in many fields. In ethics and politics, Ayn Rand, Philippa Foot, and Alasdair MacIntyre are among these thinkers.

Criticism of Aristotle

Aristotle is generally counted as one of the 'great philosophers'. However, during his lifetime and for many years afterwards, his reputation was rather less golden. Indeed, the renowned 'sceptic', Timon of Philus, sneered at "the sad chattering of the empty Aristotle" while Theocritus of Chios wrote a rather unkind epigram on him which runs:

The empty-headed Aristotle rais'd This empty tomb to Hermias the Eunuch, The ancient slave of the ill-us'd Eubulus. (Who for his monstrous appetite, preferred The Bosphorus to Academia's groves.)

In the Nineteenth Century, the scientist, John Tyndall, complained that Aristotle's statements were most accepted when they were most incorrect, whilst in the Twentieth, Karl Popper accused Aristotle of having held up the development of thought itself. [11]

The development of thought since Aristotle, could, I think, be summed up by saying that every discipline, as long as it used the Aristotelian method of definition, has remained arrested in a state of empty verbiage and barren scholasticism, and that the degree to which the various sciences have been able to make any progress depended on the degree to which they have been able to get rid of this essentialist method. (This is why so much of our "social science" still belongs to the Middle Ages).[12]

Notes

- ↑ Aristotle Life and Work King, Peter J., Pembroke College, Oxford University

- ↑ Aristotle Biography O'Connor, John J. and Robertson, Edmund F. (1999). MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland

- ↑ Ross, D. Aristotle. Routledge Press, 2004. 336 pp.

- ↑ Barnes, J. The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle. Cambridge University Press, 1995. 404 pp.

- ↑ p. 3, Barnes

- ↑ This is connected with his valuation of ‘reasonable opinions.’ Cf. the discussion at Barnes, 15ff.

- ↑ 'A large part of an early version of this section was taken from the entry on Aristotle in 'Essentials of Philosophy and Ethics', edited by Martin Cohen, (Hodder Arnold 2006) and donated to the Citizendium by the author.

- ↑ Cohen SM, Curd P, Reeve CDC. (2011) Readings in Ancient Greek Philosophy: From Thales to Aristotle. Fourth Edition. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, ISBN 9781603844635; ISBN 9781603844628; Adobe PDF ebook ISBN 9781603845977.

- ↑ Internal CZ Link to History of Astronomy

- ↑ Aristotelian Cosmology Wudka, Jose (1998) Relativity and Cosmology, Physics Dept. University of California, Riverside; On the Heavens Stock, J.L (trans); Aristotle Life and Work King, Peter J., Pembroke College, Oxford University; Aristotle Biography O'Connor, John J. and Robertson, Edmund F. (1999). MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland; William M. Calder III (ed.), Werner Jaeger Reconsidered. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992. Illinois Classical Studies; Translated by W. D. Ross Internet Classics Archive, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- ↑ Philosophical Tales, by Martin Cohen, Blackwell 2008 p14

- ↑ K. R. Popper, The open society and its enemies. Vol. 2. Hegel and Marx. London: Routledge, (1945). p. 9