imported>Chunbum Park |

imported>John Stephenson |

| (198 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| A '''[[cypherpunk]]''' is an activist advocating widespread use of strong cryptography as a route to social and political change. Cypherpunks have been engaged in an active movement since the late 1980s, heavily influenced by the hacker tradition and by libertarian ideas. Many cypherpunks were quite active in the intense political and legal controversies around cryptography of the 90s, and most have remained active into the 21st century.

| | {{:{{FeaturedArticleTitle}}}} |

| | | <small> |

| The basic ideas are in this quote from the ''Cypherpunk Manifesto'':

| | ==Footnotes== |

| | | {{reflist|2}} |

| {{quotation|Privacy is necessary for an open society in the electronic age. ... | | </small> |

| | |

| We cannot expect governments, corporations, or other large, faceless organizations to grant us privacy ...

| |

| | |

| We must defend our own privacy if we expect to have any. ...

| |

| | |

| Cypherpunks write code. We know that someone has to write software to defend privacy, and ... we're going to write it. ... }}

| |

| | |

| Many cypherpunks are technically quite sophisticated; they do understand ciphers and are capable of writing software. Some are or were quite senior people at major hi-tech companies and others are well-known researchers. However, the "punk" part of the name indicates an attitude:

| |

| | |

| {{quotation|We don't much care if you don't approve of the software we write. We know that software can't be destroyed and that a widely dispersed system can't be shut down.}} | |

| | |

| {{quotation|This is crypto with an attitude, best embodied by the group's moniker: Cypherpunks.}}

| |

| | |

| The first mass media discussion of cypherpunks was in a 1993 Wired article by Steven Levy titled ''Code Rebels'':

| |

| | |

| {{quotation|The people in this room hope for a world where an individual's informational footprints -- everything from an opinion on abortion to the medical record of an actual abortion -- can be traced only if the individual involved chooses to reveal them; a world where coherent messages shoot around the globe by network and microwave, but intruders and feds trying to pluck them out of the vapor find only gibberish; a world where the tools of prying are transformed into the instruments of privacy.}} | |

| | |

| {{quotation|There is only one way this vision will materialize, and that is by widespread use of cryptography. Is this technologically possible? Definitely. The obstacles are political -- some of the most powerful forces in government are devoted to the control of these tools. In short, there is a war going on between those who would liberate crypto and those who would suppress it. The seemingly innocuous bunch strewn around this conference room represents the vanguard of the pro-crypto forces. Though the battleground seems remote, the stakes are not: The outcome of this struggle may determine the amount of freedom our society will grant us in the 21st century. To the Cypherpunks, freedom is an issue worth some risk.}}

| |

| | |

| The three masked men on the cover of that edition of Wired were prominent cypherpunks Tim May, Eric Hughes and John Gilmore.

| |

| | |

| Later, Levy wrote a book ''Crypto: How the Code Rebels Beat the Government — Saving Privacy in the Digital Age'' covering the "crypto wars" of the 90s in detail. "Code Rebels" in the title is almost synonymuous with "cypherpunks".

| |

| | |

| The term "cypherpunk" is mildly ambiguous. In most contexts in means anyone advocating cryptography as a tool for social change. However, it can also be used to mean a participant in the cypherpunks mailing list described below. The two meanings obviously overlap, but they are by no means synonymous.

| |

| | |

| Documents exemplifying cypherpunk ideas include the ''Crypto Anarchist Manifesto'', the ''Cypherpunk Manifesto'' and the ''Ciphernomicon''.

| |

| | |

| == Cypherpunk issues ==

| |

| | |

| Through most of the 90s the cypherpunks mailing list had extensive discussions of the public policy issues related to cryptography and on the politics and philosophy of concepts such as anonymity, pseudonyms, reputation, and privacy. Of course these discussions are continuing elsewhere since the list shut down.

| |

| | |

| In at least two senses, people on the list were ahead of more-or-less everyone else. For one thing, the list was discussing questions about privacy, government monitoring, corporate control of information, and related issues in the early 90s that did not become major topics for broader discussion until ten years or so later. For another, at least some list participants were more radical on these issues than almost anyone else.

| |

| | |

| The list had a range of viewpoints and there was probably no completely unanimous agreement on anything. The general attitude, though, definitely put personal privacy and personal liberty above all other considerations.

| |

| ''[[Cypherpunk|.... (read more)]]''

| |

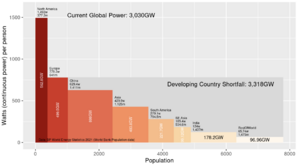

After decades of failure to slow the rising global consumption of coal, oil and gas,[1] many countries have proceeded as of 2024 to reconsider nuclear power in order to lower the demand for fossil fuels.[2] Wind and solar power alone, without large-scale storage for these intermittent sources, are unlikely to meet the world's needs for reliable energy.[3][4][5] See Figures 1 and 2 on the magnitude of the world energy challenge.

Nuclear power plants that use nuclear reactors to create electricity could provide the abundant, zero-carbon, dispatchable[6] energy needed for a low-carbon future, but not by simply building more of what we already have. New innovative designs for nuclear reactors are needed to avoid the problems of the past.

(CC) Image: Geoff Russell Fig.1 Electricity consumption may soon double, mostly from coal-fired power plants in the developing world.

[7] Issues Confronting the Nuclear Industry

New reactor designers have sought to address issues that have prevented the acceptance of nuclear power, including safety, waste management, weapons proliferation, and cost. This article will summarize the questions that have been raised and the criteria that have been established for evaluating these designs. Answers to these questions will be provided by the designers of these reactors in the articles on their designs. Further debate will be provided in the Discussion and the Debate Guide pages of those articles.

- ↑ Global Energy Growth by Our World In Data

- ↑ Public figures who have reconsidered their stance on nuclear power are listed on the External Links tab of this article.

- ↑ Pumped storage is currently the most economical way to store electricity, but it requires a large reservoir on a nearby hill or in an abandoned mine. Li-ion battery systems at $500 per KWh are not practical for utility-scale storage. See Energy Storage for a summary of other alternatives.

- ↑ Utilities that include wind and solar power in their grid must have non-intermittent generating capacity (typically fossil fuels) to handle maximum demand for several days. They can save on fuel, but the cost of the plant is the same with or without intermittent sources.

- ↑ Mark Jacobson believes that long-distance transmission lines can provide an alternative to costly storage. See the bibliography for more on this proposal and the critique by Christopher Clack.

- ↑ "Load following" is the term used by utilities, and is important when there is a lot of wind and solar on the grid. Some reactors are not able to do this.

- ↑ Fig.1.3 in Devanney "Why Nuclear Power has been a Flop"