RNA interference/Citable Version: Difference between revisions

imported>David Tribe |

imported>David Tribe |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

====Cleavage or mRNA or interference with translation are both possible RNAi outcomes==== | ====Cleavage or mRNA or interference with translation are both possible RNAi outcomes==== | ||

The Dicer enzyme then cuts 20-25 nucleotides from the base of the | The Dicer enzyme then cuts 20-25 nucleotides from the base of the hairpin to release the mature miRNA. If base-pairing with the target is perfect or near-perfect this may result in cleavage of messenger RNA ([[mRNA]]). This is quite similar to the siRNA function, however, many miRNA's will base pair with mRNA with an imperfect match. In such cases, the miRNA causes the inhibition of translation and prevents normal function. Consequently, the RNAi machinery is important to regulate [[Endogenous#Biology|endogenous gene]] activity. This effect was first described for the ''C. elegans'' in 1993 by R. C. Lee ''et al'' of Harvard University. In plants, this mechanism was first shown in the "JAW microRNA" of ''[[Arabidopsis thaliana|Arabidopsis]]''; it is involved in regulating several genes that control the plant's shape. Genes have been found in bacteria that are similar in the sense that they control mRNA abundance or translation by binding an mRNA by base pairing, however they are not generally considered to be miRNA's because the Dicer enzyme is not involved.<ref>Lee RC ''et al'' (1993) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14 ''Cell'' '''75''':843-54. | ||

* Palatnik JF ''et al'' (2003). Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs ''Nature'' '''425''':257-63 | * Palatnik JF ''et al'' (2003). Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs ''Nature'' '''425''':257-63 | ||

* Morita T ''et al'' (2006) Translational repression is sufficient for gene silencing by bacterial small noncoding RNAs in the absence of mRNA destruction ''Proc Natl Acad Sci USA'' '''103''':4858-63</ref> | * Morita T ''et al'' (2006) Translational repression is sufficient for gene silencing by bacterial small noncoding RNAs in the absence of mRNA destruction ''Proc Natl Acad Sci USA'' '''103''':4858-63</ref> | ||

Revision as of 23:15, 1 January 2007

RNA interference (RNAi) is a mechanism in eukaryotic cells that is triggered when these cells are exposed to certain double-stranded ribose nucleic acid (dsRNA) polymeric molecules. This process has been detected in many organisms, including animal, plant and protist cells. The distinguishing characteristic of RNAi is destruction of cellular messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules sharing at least some of the sequence characteristics of dsRNA trigger molecules to which the cells have been exposed.

RNA is a polymer of nucleotide bases that carries information stored as a DNA code in genes, to regions of the cell involved in synthesis of protein molecules, where that genetic information is used for assembling proteins. Understanding the flow of information from DNA to mRNA to proteins - a process known as gene expression (see figure) - is helpful for understanding RNAi, as RNAi potently inhibits this information flow, and thus effectively silences gene expression. Hundreds of human genes are affected by natural regulatory circuits that involve RNAi mediated processes.

RNAi is a major technological breakthrough In biological research, perhaps as important as the development of PCR, the technique that enabled even tiny amounts of specific mRNAs to be measured easily. In experiments using RNAi in the fly Drosophila or in the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, the effect of the loss of function of every known gene on a molecular pathway, cellular structure, or organism phenotype can now be determined rapidly and easily.[1]

Discovery of unexpected new coordinating roles for RNA

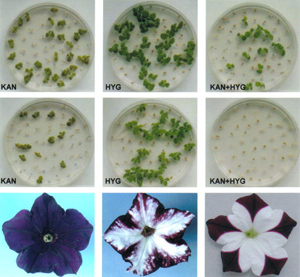

The revolutionary discovery of RNAi resulted from the unexpected outcome of experiments by plant scientists in the USA and the Netherlands.[2] These scientists were trying to produce petunia plants with improved flower colors by introducing extra copies of a gene encoding an enzyme for flower pigmentation. Surprisingly, many plants with extra copies of the gene did not show the expected deep purple or deep red flowers, but had fully white or partially white flowers (see figure). When scientists looked more closely, they found that both the endogenous genes and the newly introduced transgenes, had been 'turned off'. (The term transgene refers to genes introduced into a plant by genetic manipulation from another species). Accordingly, the phenomenon was first called 'co-suppression of gene expression' but the molecular mechanism was unknown.

A few years later, plant virologists made a similar observation during experiments aimed at increasing plants' resistance to viruses. They knew that plants expressing virus-specific proteins could show enhanced tolerance, or even resistance, to viral infection, but to their surprise they found the same effect in plants that carried only short regions of viral RNA sequences, sequences too short to code for any viral protein. They concluded that viral RNA produced by transgenes could attack incoming viruses and stop them from spreading throughout the plant. They did the reverse experiment and put short pieces of plant gene sequences into plant viruses. Indeed, after infecting plants with these modified viruses the expression of the targeted plant gene was suppressed. They called this 'virus-induced gene silencing' ('VIGS'). These phenomena are collectively called post transcriptional gene silencing.[3]

Subsequently, many laboratories began to look for this phenomenon in other organisms. In 1998, Andrew Fire and Craig C. Mello (at the Carnegie Institution of Washington and the University of Massachusetts Cancer Center respectively) reported a potent gene silencing effect after injecting double stranded RNA into C. elegans[4]. They coined the term RNAi, and their discovery of RNAi in C. elegans is particularly notable, as it represented the first identification of the causative agent (double stranded RNA) of this hereto inexplicable phenomenon. In October 2006, Fire and Mello won the Nobel Prize for Medicine for their discoveries on gene silencing by RNAi.[5]

Guide RNAs help proteins silence genes

RNAi is but one of a group of mechanistically related gene silencing phenomena which have in common the existence in cells of small RNA molecules, often derived from longer dsRNA precursors, or from double-stranded regions of hair-pin shaped single-stranded RNA molecules. In these 'RNA silencing' mechanisms, small RNA molecules appropriately called 'guige' RNAs silence gene expression by guiding protein complexes to their target genes or target RNA messages. The mechanisms vary from one other for instance in which other cell components are involved and whether or DNA or mRNA is the main target for silencing. RNA silencing pathways exist in animals, plants, protists, and fungi. Despite their confusing variety in different organisms, many gene silencing responses share common mechanistic features, suggesting a common origin early in evolution.

The use of RNAi to reduce gene expression in plants (now usually called gene 'knockdown') has been common in recent years. Single-stranded antisense RNA that hybridized to a complementary, single-stranded, sense messenger RNA was deliberately introduced into plant cells to achieve knockdown. While plant biologists first believed that the resulting dsRNA helix could not be translated into a protein, it is now clear that the dsRNA triggered a RNAi response. The experimental use of dsRNA in biological research became more widespread after the discovery of the RNAi machinery, first in petunias and later in roundworms (C. elegans).

Before RNAi was well characterized, it was called by several other names, including 'post transcriptional gene silencing' and 'transgene silencing'. Only after these phenomena were characterized at the molecular level was it obvious that they were the same phenomenon.

Biological origins and roles

It has been suggested that the basic RNAi machinery was present is the common ancestor of all eukaryotic cells, with an ancestral role in defence against genetic parasites.[6] In current day organisms the RNAi pathway does indeed play a role in defending against viruses and other foreign genetic material, both in animals (as part of the immune response) but especially in plants where it may protect against the self-propagation of parasitic or selfish DNA such as transposons. The pathway is conserved across all eukaryotes, although it has been independently recruited to play other functions such as histone modification,the reorganization of genomic regions with complementary sequence to induce heterochromatin formation, and maintenance of centromeric heterochromatin. [7]

Primary-miRNAs are precursors for natural miRNAs

The native cellular RNAi machinery is used by both plants and animals to regulate groups of tens or even hundreds of cellular genes via key regulatory genes that produce natural substrates for the Dicer enzyme that is involved in the RNAi response. These natural Dicer substrates are called primary-micro RNAs. For producing micro RNAs (miRNAs), certain parts of the genome are transcribed into relatively short single-stranded RNA molecules that fold back on themselves in a hairpin shape to create a region with double stranded primary miRNA structure (pri-miRNA). By 2006, thousands of miRNAs had been identified in plants and animals, including more than 470 in humans.

Cleavage or mRNA or interference with translation are both possible RNAi outcomes

The Dicer enzyme then cuts 20-25 nucleotides from the base of the hairpin to release the mature miRNA. If base-pairing with the target is perfect or near-perfect this may result in cleavage of messenger RNA (mRNA). This is quite similar to the siRNA function, however, many miRNA's will base pair with mRNA with an imperfect match. In such cases, the miRNA causes the inhibition of translation and prevents normal function. Consequently, the RNAi machinery is important to regulate endogenous gene activity. This effect was first described for the C. elegans in 1993 by R. C. Lee et al of Harvard University. In plants, this mechanism was first shown in the "JAW microRNA" of Arabidopsis; it is involved in regulating several genes that control the plant's shape. Genes have been found in bacteria that are similar in the sense that they control mRNA abundance or translation by binding an mRNA by base pairing, however they are not generally considered to be miRNA's because the Dicer enzyme is not involved.[8]

Gene knockdown

RNAi has recently been used to study the function of genes in model organisms. Double-stranded RNA for a gene of interest is introduced into a cell or organism, where, by RNAi, it often causes a drastic decrease in production of the protein the gene codes for. Studying the effects of this can yield insights into the protein's role and function. As RNAi may not totally abolish expression of the gene, this is sometimes referred as a "knockdown", to distinguish it from "knockout" in which expression of a gene is entirely eliminated by removing or destroying its DNA sequence.

Most functional genomics applications of RNAi have used the nematode C. elegans and the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, both common model organisms in genetics research.[9] C. elegans is particularly useful for RNAi research because the effects of the gene silencing are generally heritable and because delivery of the dsRNA is exceptionally easy. Via a mechanism whose details are poorly understood, bacteria such as E coli that carry the desired dsRNA can be fed to the worms and will transfer their RNA payload to the worm via the intestinal tract. This "delivery by feeding" yields essentially the same magnitude of gene silencing as do more costly and time-consuming traditional delivery methods, such as soaking the worms in dsRNA solution and injecting dsRNA into the gonads.[10]

Role in medicine

The dsRNAs that trigger RNAi might be usable as drugs. The first application to reach clinical trials is in the treatment of macular degeneration. RNAi has also proved able to completely reverse induced liver failure in mouse models (laboratory mice in which liver failure has been induced experimentally). Another speculative use of dsRNA is in the repression of essential genes in eukaryotic human pathogens or viruses that are dissimilar from any human genes; this would be analogous to how existing drugs work.

RNAi interferes with the translation process of gene expression and appears not to interact with the DNA itself. Proponents of therapies based on RNAi suggest that the lack of interaction with DNA might alleviate some patients' concerns about alteration of their DNA (as practiced in gene therapy), and suggest that this treatment would likely be no more feared than taking any prescription drug. For this reason RNAi and therapies based on RNAi have attracted much interest in the pharmaceutical and biotech industries. More recently, RNAi researchers have used RNAi to silence the expression of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in mice.

Role in plant science

RNAi is widely used to probe gene functions in plants. An example is a recent study from the laboratory of Jorge Dubcovsky where it was necessary to determine the function of a gene GPC-B1 that was thought to be involved in regulating wheat leaf senescence (and to affect cereal protein content) [11]. This laboratory used RNAi to knockdown expression of the GPC-B1 gene in cereal wheat and found spectacular changes in grain germination after knockdown. The GPC-B1 knockdown wheat variety showed 30% less grain protein, zinc and iron, without differences in grain size, and verified that a single gene was responsible for all the effects. They suggest that increased expression of the gene cam improve grain protein content and nutritional value.

More practically, Australia's CSIRO has developed a new experimental wheat variety with the potential to provide benefits in the areas of bowel health, diabetes and obesity. In this case, RNAi was used in wheat to increase the content of amylose, a form of starch that is more resistant to digestion [12].

CSIRO and others have argued that cisgenic plants - that is plants created by genetic manipulation using RNAi (which they dub "GM-lite")- pose less risks than addition of genes from other species (transgenics) as (they argue) new proteins are unlikely to be produced. [13]

Cellular and molecular mechanisms

Double-stranded regions of RNA are the triggers for RNAi

There are two types of triggers for RNAi. These (1) fully double stranded RNA (dsRNA, and (2) 'hairpin' forms of single-stranded RNA in which the 'stem' of the RNA hairpin structure has complementary RNA base-pairing between two different parts of the same RNA strand (see figure to left). These two types of trigger structure can both be substrates for a ribonuclease enzyme that is appropriately named 'Dicer'.

Dicer

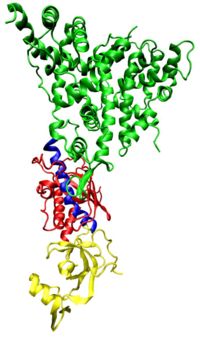

The RNAi process requires active participation of cellular machinery, and the properties of the Dicer enzyme are important for understanding how this process occurs.

Dicer has two active sites, both able to cleave its substrate RNAs. These active sites are separated some distance from one another in the Dicer enzyme (see figure to the right ) and this explains the size of the RNA fragments they produce when they act on a double stranded RNA (dsRNA) target, a dicing process which is an early step in the cellular pathway that brings about RNAi.[14]

Multi-protein transcriptional silencing complexes generate the guide strand RNA

Dicer binds to and cleaves short double-stranded trigger RNA molecules (dsRNA) in two positions to produce double-stranded fragments of 21-23 base pairs with two-base single-stranded overhangs on each end. The short double-stranded fragments produced by Dicer when it acts on dsRNA are called small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), or miRNA when it acts of the cell's own transcribed, hairpin-forming miRNA precursors. One RNA strand - the guide strand - from these siRNAs [15] is generated by an aggregate of several proteins, including DICER, called the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC)[16].

Cellular RNA-dependent RNA polymerase can also produce double-stranded triggers

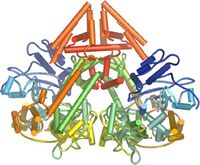

In plants, protozoa, fungi, and nematodes, a cell-encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (cRdRP, RDR; see figures) produces fully dsRNA trigger molecules for RNA from single-stranded RNA. The structure of cell-encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Neurospora crassa (shown below) is a relatively compact dimeric molecule and its core is a catalytic apparatus and protein folding that is strikingly similar to the catalytic core of the DNA-dependent RNA polymerases responsible for transcription[17].

Argonautes are slicers that cleave mRNA with a little help from their friends

The RISC complex containing DICER has an important role in processing trigger molecules to generate the short single stranded effectors of interference, termed the guide strand. The human RISC complex shows a nearly 10-fold greater activity using the pre-miRNA Dicer substrate over duplex siRNA. RISC can distinguish the guide strand of the siRNA from the passenger strand, and specifically incorporates only the guide strand.[18]

After integration into the RISC, single guide strands of RNA, either from siRNAs or miRNAs, base pair to their target mRNA and induce the RISC component protein Argonaute to cleave the mRNA, thereby preventing it from being used as a translation template. Proteins with similar sequence to Argonaute (e.g. RDE-1, P-element associated wimpy testes (Piwi)) are present in nearly every eukaryote, from fungi to plants, flies, and mammals, often as gene families [19].

Organisms vary in their cells' ability to take up foreign dsRNA and use it in the RNAi pathway. The effects of RNA interference are both systemic and heritable in plants and in C. elegans, although not in Drosophila or mammals because of the absence of RNA replicase in these organisms. In plants, RNAi is thought to propagate through cells via the transfer of siRNAs through plasmodesmata.[16]

References

Citations

- ↑ Zamore PD (2006) Essay: RNA interference: big applause for silencing in Stockholm Cell 127:1083-1086 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.001 PMID 17174883

- ↑ Napoli C et al(1990) Introduction of a chalcone synthase gene into Petunia results in reversible co-suppression of homologous genes in trans Plant Cell 2: 279-89

- ↑ Fully discussed in Matzke MA, Matzke AJM (2004) Planting the Seeds of a New Paradigm. PLoS Biol 2(5): e133 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020133

- ↑ Fire A et al (1998) Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans Nature 391:806-11

- ↑ Review for the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Advanced Information: RNA interference by Bertil Daneholt.

- ↑ Cerutti H, Casas-Mollano JA (2006) On the origin and functions of RNA-mediated silencing: from protists to man.Curr Genet 50:81-99 PMID 16691418

- ↑ Saito K et al (2006) Specific association of Piwi with rasiRNAs derived from retrotransposon and heterochromatic regions in the Drosophila genome Genes Dev 20:2214-22 PMID 16882972

- Stram Y, Kuzntzova L (2006) Inhibition of viruses by RNA interference Virus Genes 32:299-306

- Tijsterman M et al(2002) The genetics of RNA silencing Ann Rev Genet 36:489-519 PMID 12429701

- Cerutti H, Casas-Mollano JA (2006) On the origin and functions of RNA-mediated silencing: from protists to man Curr Genet 50:81-99

- Holmquist GP, Ashley T (2006) Chromosome organization and chromatin modification: influence on genome function and evolution. Cytogenet Genome Res 114:96-125

- Volpe TA et al (2002) Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi Science 297:1833-7 PMID 12193640

- ↑ Lee RC et al (1993) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14 Cell 75:843-54.

- Palatnik JF et al (2003). Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs Nature 425:257-63

- Morita T et al (2006) Translational repression is sufficient for gene silencing by bacterial small noncoding RNAs in the absence of mRNA destruction Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:4858-63

- ↑ Dzitoyeva S et al (2003) Gamma-aminobutyric acid B receptor 1 mediates behavior-impairing actions of alcohol in Drosophila: adult RNA interference and pharmacological evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:5485-90 PMID 12692303

- ↑ Fortunato A, Fraser AG (2005) Uncover genetic interactions in Caenorhabditis elegans by RNA interference Biosci Rep 25:299-307 PMID 16307378

- ↑ Wheat gene may boost foods' nutrient content

- Cristobal Uauy C et al (2006). A NAC gene regulating senescence improves grain protein, zinc, and iron content in wheat Science 314:1298-1301 DOI: 10.1126/science.1133649

- ↑ Regina A et al (2006) High-amylose wheat generated by RNA interference improves indices of large-bowel health in rats PNAS

- ↑ Do cisgenic plants warrant less stringent oversight? Nature Biotechnol 24. This letter argues there are strong reasons for legislators to differentiate cisgenic (GM lite) from transgenic plants.

- ↑ Bernstein E et al (2001) Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference Nature 409:363-6 PMID 11201747. Comment in Baulcombe D (2001) RNA silencing. Diced defence. Nature 409:295-6

- Hammond SM et al (2001) Argonaute2, a link between genetic and biochemical analyses of RNAi Science 293:1146–50 PMID 11498593

- Molecular characterization of a mouse cDNA encoding Dicer, a ribonuclease III ortholog involved in RNA interference Mamm Genome (2002} PMID 11889553

- An RNA-directed nuclease mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells Nature (2000) PMID 10749213

- The dsRNA binding protein RDE-4 interacts with RDE-1, DCR-1, and a DExH-box helicase to direct RNAi in C. elegans Cell (2002) PMID 12110183

- R2D2, a bridge between the initiation and effector steps of the Drosophila RNAi pathway Science (2003) PMID 14512631

- Macrae IJ et al. (2006) Structural basis for double-stranded RNA processing by Dicer. Science 311:195-8. PMID 16410517

- ↑ Tomari Y et al (2004) A protein sensor for siRNA asymmetry. Science '306:1377-80

- Schwarz DS et al (2003) Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex Cell 115:199-208 PMID 14567917

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Lodish H et al (2004) Molecular Cell Biology 5th ed. WH Freeman: New York, NY

- ↑ Salgado PS et al (2006) The structure of an RNAi polymerase links RNA silencing and transcription PLoS Biol 4(12), e434 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040434

- ↑ Gregory RI (2005) RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing.Cell.123:631-40 PMID 16271387

- ↑ Girard A et al (2006) A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins Nature 442:199-202 PMID 16751776

- Baumberger N, Baulcombe DC (2005) Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE1 is an RNA Slicer that selectively recruits microRNAs and short interfering RNAs Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:11928-33 PMID 16081530

Further reading

- Ahlquist P (2002) RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, viruses, and RNA silencing Science 296:1270-73

- Baulcombe D (2004) RNA silencing in plants Nature 431:356–63

- Cogoni C, Macino G (1999) Gene silencing in Neurospora crassa requires a protein homologous to RNA-dependent RNA polymerase Nature 399:166–9

- Lippman Z, Martienssen R (2004) The role of RNA interference in heterochromatic silencing. Nature 431:364–70.

- Makeyev EV, Bamford DH (2002) Cellular RNA-dependent RNA polymerase involved in posttranscriptional gene silencing has two distinct activity modes. Mol Cell 10:1417–27

- Matzke M et al (2001) RNA: guiding gene silencing Science 293, 1080-3

- Mello CC, Conte D Jr (2004) Revealing the world of RNA interference Nature 431:338–42

- Sharp PA (2001) RNA interference--2001 Genes Dev 15:485-90

- Sijen T et al (2001) On the role of RNA amplification in dsRNA-triggered gene silencing Cell 107:465–76

See also

External links

- Matzke MA, Matzke AJM (2004) Planting the Seeds of a New Paradigm. PLoS Biol 2(5): e133 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020133, a PLoS primer on plant biologists and the understanding of RNAi

- Animation of the RNAi process, from Nature

- siRNA Database

- NOVA scienceNOW explains RNAi - A 15 minute video of the Nova broadcast that aired on PBS, July 26, 2005

- RNA interference (RNAi) Database

- The Genetics of RNA silencing.