Barnardius zonarius/Citable Version: Difference between revisions

imported>D. Matt Innis (paste draft to current approved) |

imported>D. Matt Innis m (Protected "Barnardius zonarius": protect approved [edit=sysop:move=sysop]) |

Revision as of 09:14, 14 September 2007

| Australian Ringneck | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Australian Ringneck.Template:Photo

| ||||||||||||||||||

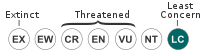

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||||

| Barnardius zonarius (Shaw, 1805) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Subspecies | ||||||||||||||||||

|

B. z. zonarius | ||||||||||||||||||

| Synonyms | ||||||||||||||||||

The Australian Ringneck (Barnardius zonarius) is a parrot native to all mainland Australian states. Except for extreme tropical and highland areas, the species has adapted to all conditions. Traditionally, two species were recognized in the genus Barnardius, the Port Lincoln Parrot (Barnardius zonarius) and the Mallee Ringneck Barnardius barnardi)[2], but the two species readily interbred at the contact zone and are now considered one species[3][4]. Currently, four subspecies are recognised, each with a distinct range.

In Western Australia (Perth), the Ringneck competes for nesting space with the Rainbow Lorikeet, an introduced species.[5] To protect the Ringneck, culls of the lorikeet are sanctioned by authorities in this region.[6] Overall, though, the Ringneck is not a threatened species.[1]

Taxonomy and naming

The Australian Ringneck was first described by the English naturalist George Shaw in 1805. Currently, four subspecies of Ringneck are recognized, all of which have been described as distinct species in the past: [4][7]

- The Port Lincoln Parrot or Port Lincoln Ringneck (B. z. zonarius (Shaw, 1805)) is common from Port Lincoln in the south east to Alice Springs in the north east, and from the Karri and Tingle forests of South Western Australia up to the Pilbara district.

- The Twenty Eight (B. z. semitorquatus (Quoy & Gaimard, 1830)), named in imitation of its distinctive 'twentee-eight' call, is found in the south western forests of coastal and subcoastal Western Australia.

- The Mallee Ringneck (B. z. barnardi (Vigors & Horsfield, 1827)) inhabits New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and Victoria.

- The Cloncurry Parrot (B. z. macgillivrayi (North, 1900)) is found from the Lake Eyre basin in the Northern Territory to the North gulf of Queensland.

The classification of this species is still debated, and recent molecular research has found that all subspecies are very closely related [4]. Several other subspecies have been described, but are considered synonyms with one of the above subspecies. B. z. occidentalis has been synomised with B. z. zonarius.[8] Intermediates exist between all subspecies except for between B. z. zonarius and B. z. macgillivrayi.[4][9]

The species is considered not threatened,[1] but in Western Australia, the Twenty Eight subspecies (B. z. semitorquatus) gets locally displaced by the introduced Rainbow Lorikeets that aggressively compete for nesting places.[5] The Rainbow Lorikeet is considered a pest species in Western Australia and is subject to eradication in the wild.[6]

Description

The subspecies of the Australian Ringneck differ considerably in coloration[2]. It is a medium size species of around 33 cm long. The basic colour is green, and all four subspecies have the characteristic yellow ring around the hindneck; wings and tail are a mixture of green and blue. The B. z. zonarius and B. z. semitorquatus subspecies have a dull black head; back, rump and wings are brilliant green; throat and breast bluish-green. The difference between these two subspecies is that B. z. zonarius has a yellow abdomen while B. z. semitorquatus has a green abdomen; the latter has also a prominent crimson frontal band that the former lacks. The two other subspecies differ from these subspecies by the bright green crown and nape and blush cheek-patches. The underparts of B. z. barnardi are turquoise-green with an irregular orange-yellow band across the abdomen; the back and mantle are deep blackish-blue and this subspecies has a prominent red frontal band. The B. z. macgillivrayi is generally pale green, with a wide uniform pale yellow band across the abdomen.

Behaviour

The Australian Ringneck is active during the day and can be found in eucalypt woodlands and eucalypt-lined watercourses. The species is gregarious and depending on the conditions can be resident or nomadic. As most parrots, it breeds in tree cavities. Breeding season for the Northern populations starts in June or July, while the central and southern populations breed from August to February but this can be delayed when climatic conditions are unfavourable. This species eats a wide range of foods that include nectar, insects, seeds, fruit, and native and introduced bulbs. It will eat orchard-grown fruit, and is sometimes seen as a pest by farmers[2][7][10].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 BirdLife International (2004). Barnardius zonarius. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. Retrieved on 11 May 2006.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Forshaw, Joseph M.; Cooper, William T. [1973, 1978] (1981). Parrots of the World, corrected second edition. David & Charles, Newton Abbot, London. ISBN 0-7153-7698-5.

- ↑ Christidis, L. & Boles, W.E. (1994). The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories. Hawthorn East, Victoria : Royal Ornithologists Union Monograph Vol. 2 112 pp.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Joseph, L. & Wilke, T. 2006. Molecular resolution of population history, systematics and historical biogeography of the Australian ringneck parrots Barnardius: are we there yet? Emu 106: 49-62

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Forshaw J. M. (2002) Australian Parrots. Alexander Editions, Brisbane.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Declared pests by the Department of Agriculture of Western Australia

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/abrs/fauna/details.pl?pstrVol=AVES;pstrTaxa=1169;pstrChecklistMode=2

- ↑ Schodde, R. & Mason, I.J. (1997) Aves (Columbidae to Coraciidae). In, Houston, W.W.K. & Wells, A. (eds) Zoological Catalogue of Australia. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing, Australia Vol. 37.2 xiii 440 pp.

- ↑ Ford, J. (1987) Hybrid Zones in Australian Birds. Emu 87: 158-178

- ↑ Department of Agriculture, Western Australia: Parrot damage in agroforestry in the greater than 450 mm rainfall zone of Western Australia