Spanish language: Difference between revisions

imported>John Stephenson (categories) |

imported>Pat Palmer (→Writing system: removing link to Ñ) |

||

| Line 314: | Line 314: | ||

{{main|Writing system of Spanish}} | {{main|Writing system of Spanish}} | ||

Spanish is written using the [[Latin alphabet]], with the addition of the character " | Spanish is written using the [[Latin alphabet]], with the addition of the character "ñ" (''eñe''), an "n" with [[tilde]]. Historically, the [[digraph]]s "ch" ({{lang|es|''che''}}), "ll" ({{lang|es|''elle''}}), and "rr" ({{lang|es|''erre doble''}}, double "r") were regarded as single letters, with their own names and places in the alphabet (''a, b, c, ch, d…, l, ll, m, n, ñ, o… r, rr, s…''), because each represents a single phoneme ({{IPA|/tʃ/}}, {{IPA|/ʎ/}}, and {{IPA|/r/}}, respectively). Since 1994, these letters are to be replaced with the appropriate letter pair in [[collation]]. Spelling remains visually unchanged, but words with "ch" are now alphabetically sorted between those with "ce" and "ci", instead of following "cz", and similarly for "ll" and "rr". However, the names ''che'', ''elle'' and ''erre doble'' are still used colloquially. | ||

Excluding a very small number of regional terms such as ''México'', pronunciation can be entirely determined from spelling (see [[México#Origin and history of the name|Mexico: Origin and history of the name]]). A typical Spanish word is stressed on the [[syllable]] before the last if it ends with a vowel (not including "y") or with a vowel followed by "n" or "s", and stressed on the last syllable otherwise. Exceptions to this rule are indicated by placing an [[acute accent]] on the [[stress (linguistics)|stressed vowel]]. | Excluding a very small number of regional terms such as ''México'', pronunciation can be entirely determined from spelling (see [[México#Origin and history of the name|Mexico: Origin and history of the name]]). A typical Spanish word is stressed on the [[syllable]] before the last if it ends with a vowel (not including "y") or with a vowel followed by "n" or "s", and stressed on the last syllable otherwise. Exceptions to this rule are indicated by placing an [[acute accent]] on the [[stress (linguistics)|stressed vowel]]. | ||

Revision as of 20:03, 12 May 2007

| Spanish | |

|---|---|

| español, castellano | |

| Spoken in | Spain, Mexico, Central America, South America, the Caribbean region, Equatorial Guinea, and a significant minority in the United States |

| Total speakers | Native: 364 million Total: 400-480 million |

| Language family | Italic Romance Italo-Western Gallo-Iberian Ibero-Romance West Iberian |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | es |

| ISO 639-2 | spa |

| ISO 639-3 | spa |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. See IPA chart for English for an English-based pronunciation key. | |

Spanish (Template:Audio) is an Iberian Romance language originally from the northern area of Spain. It is the official language of Spain, most Latin American countries and Equatorial Guinea. In total, twenty nations and several territories use Spanish as both their primary and official language, more than any other language on Earth.

Spanish originated as a Latin dialect along the remote cross road strips among the Cantabria, Burgos and La Rioja provinces of Northern Spain. From there, its use gradually spread inside the Kingdom of Castile, where it evolved and eventually became the principal language of the government and trade. It was later brought to the Americas and other parts of the world in the last five centuries by Spanish explorers and colonists.

The language was spoken by roughly 364 million people worldwide in the year 2000, making Spanish the most popular Romance language and the second to fifth most spoken language by number of native speakers.[1][2][3] With a population of 103,263,388 in 2005, Mexico is the most populous Spanish-speaking country in the world.[4] It is estimated that the combined total of native and non-native Spanish speakers is 400-480 million, probably making it the third most spoken language by total number of speakers.[5][6]

Spanish is also one of six official working languages of the United Nations and one of the most used global languages. It is spoken most extensively in North and South America, certain parts of Europe, Asia, Africa and Oceania. It is also the second most widely spoken language in the United States and arguably the most popular foreign language for study in US schools and Universities.[7][8] Within the globalized market, there is currently an international expansion and recognition of the Spanish language in literature, the film industry, television (notably telenovelas) and music.

Naming

Spanish people tend to call this language español (español) when contrasting it with languages of foreign states(e.g., in a list with French and English), but call it Castilian (castellano), (i.e. from the Castile region) when contrasting it with other languages of Spain (such as Galician, Basque, and Catalan). In this manner, the Spanish Constitution of 1978 uses the term castellano to define the official language of the whole State, opposed to las demás lenguas españolas (lit. the other Spanish languages). Article III reads as follows:

- El castellano es la lengua española oficial del Estado. (…) Las demás lenguas españolas serán también oficiales en las respectivas Comunidades Autónomas…

- Castilian is the official Spanish language of the State. (…) The other Spanish languages shall also be official in the respective Autonomous Communities…

In some parts of Spain, mainly where people speak Galician, Basque and Catalan, the choice of words reveals the speakers' sense of belonging and their political views. People from bilingual areas might consider it offensive to call the language español, as that is the term that was chosen by Francisco Franco — during whose dictatorship the use of regional languages was discouraged — and because it connotes that Basque, Catalan and Galician are not languages of Spain. On the other hand, more nationalist speakers (both Spanish and regional nationalists) might prefer español either to reflect their belief in the unity of the Spanish State or to denote the perceived detachment between their region and the rest of the State. However, most people in Spain, regardless of place of origin, use Spanish or Castilian indistinctively.

Some philologists use "Castilian" only when speaking of the language spoken in Castile during the Middle Ages, stating that it is preferable to use "Spanish" for its modern form. The subdialect of Spanish spoken in most parts of modern day Castile can also be called "Castilian". This dialect differs from those of other regions of Spain (Andalusia for example); the Castilian dialect is almost exactly the same as standard Spanish.

Some Spanish speakers consider castellano a generic term with no political or ideological links, much as "Spanish" is in English.

Spanish/Castilian has closest affinity to the other West Iberian Romance languages. Most are mutually intelligible among speakers without too much difficulty. It has different common features with Catalan, an East-Iberian language which exhibits many Gallo-Romance traits. Catalan is more similar to Occitan than Spanish and Portuguese are to each other.

- Galician (galego)

- Portuguese (português)

- Catalan (català)

- Asturian (asturianu)

- Aragonese (fabla)

- Occitan (aranès)

- Ladino (Djudeo-espanyol, sefardí)

Vocabulary comparison

| Latin | Spanish | Portuguese | Catalan | Italian | French | Romanian | Meaning and notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nos | nosotros | nós | nosaltres | noi (noi altri in Southern Italian dialects and languages) | nous (nous autres in Quebec French) | noi | we(-others) |

| fratrem germānum (lit. true brother) | hermano | irmão | germà | fratello | frère | frate | brother |

| dies Martis (Classical) |

martes | terça-feira (Ecclesiastical tertia feria) |

dimarts | martedì | mardi | marţi | Tuesday |

| cantiōnem | canción | canção | cançó | canzone | chanson | cântec | song |

| magis or plus | más (rarely: plus) |

mais (archaically also chus) |

més | più | plus | mai | more |

| manūm sinistram | mano izquierda

(archaically also siniestra) |

mão esquerda (archaically also sẽestra) |

mà esquerra | mano sinistra | main gauche | mâna stângă | left hand (Basque: esku ezkerra) |

| nihil or nullam rem natam (lit. no thing born) |

nada | nada (archaically also rem) |

res | niente/nulla | rien | nimic | nothing |

Characterization

Spanish and Italian share a very similar phonological system and do not differ very much in grammar, vocabulary and above all morphology. Speakers of both languages can communicate relatively well: at present, the lexical similarity with Italian is estimated at 82%.[9] As a result, Spanish and Italian are mutually intelligible to various degrees. Spanish is mutually intelligible with French and with Romanian to a lesser degree (lexical similarity is respectively 75% and 71%[9]). The writing systems of the four languages allow for a greater amount of interlingual reading comprehension than oral communication would.

One defining characteristic of Spanish was the diphthongization of the Latin short vowels e and o into ie and ue, respectively, when they were stressed. Although similar sound changes can be found in other Romance languages, they were particularly significant in this one. Some examples:

- Lat. petra > Sp. piedra, It. pietra, Fr. pierre, Port./Gal. pedra "stone".

- Lat. moritur > Sp. muere, It. muore, Fr. meurt / muert, Rom. moare, Port./Gal. morre "he dies".

More peculiar to early Spanish (as in the Gascon dialect of Occitan, and possibly due to a Basque substratum) was the mutation of Latin initial f- into h- whenever it was followed by a vowel which did not diphthongate. Compare for instance:

- Lat. filium > It. figlio, Port. filho, Fr. fils, Occitan filh, Gascon hilh Sp. hijo and Ladino fijo;

- late Lat. *fabulare > Lad. favlar, Port. falar, Sp. hablar;

- but Lat. focum > It. fuoco, Port. fogo, Sp./Lad. fuego.

Some consonant clusters of Latin also produced characteristicaly different results in these languages, for example:

- Lat. clamare, acc. flammam, plenum > Lad. lyamar, flama, pleno; Sp. llamar, llama, lleno; Port. chamar, chama, cheio.

- Lat. acc. octo, noctem, multum > Lad. ocho, noche, muncho; Sp. ocho, noche, mucho; Port. oito, noite, muito.

Ladino

- Further information: Ladino language

Ladino, which is essentially medieval Castilian and closer to modern Spanish than any other language, is spoken by many descendants of the Sephardic Jews who were expelled from Spain in the 15th century. In many ways it is not a separate language but a dialect of Castilian. Ladino lacks native American vocabulary which was influential during colonial times. It does contain other vocabulary from Turkish, Hebrew and from other languages spoken wherever the Sephardic Jews settled.

Portuguese

- Further information: Differences between Spanish and Portuguese

The two major Romance languages originated in the Iberian Peninsula, Spanish and Portuguese, have generally a moderate degree of mutual intelligibility in their standard spoken forms. Spanish and Portuguese share similar grammars and a majority of vocabulary as well as a common history of Arabic influence while a great part of the peninsula was under Islamic rule (both languages expanded over Islamic territories). Their lexical similarity is estimated at 89%.[9]

History

The Spanish language developed from Vulgar Latin, with influence from Celtiberian, Basque and Arabic, in the north of the Iberian Peninsula (see Iberian Romance languages). Typical features of Spanish diachronical phonology include lenition (Latin vita, Spanish vida), palatalization (Latin annum, Spanish año) and diphthongation (stem-changing) of short e and o from Vulgar Latin (Latin terra, Spanish tierra; Latin novus, Spanish nuevo). Similar phenomena can be found in other Romance languages as well.

During the Reconquista, this northern dialect from Cantabria was carried south, and indeed is still a minority language in the northern coastal regions of Morocco.

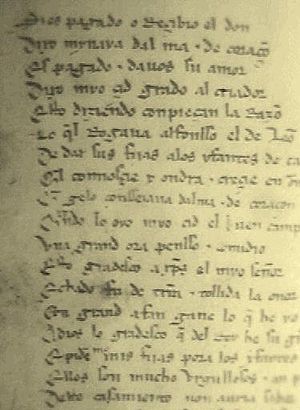

The first Latin to Spanish grammar (Gramática de la Lengua Castellana) was written in Salamanca, Spain, in 1492 by Elio Antonio de Nebrija. When Isabella of Castile was presented with the book, she asked, What do I want a work like this for, if I already know the language?, to which he replied, Your highness, the language is the instrument of the Empire.

From the 16th century onwards, the language was brought to the Americas, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Marianas, Palau, and the Philippines by Spanish colonization. Also in this epoch, Spanish became the main language of Politics and Art across the major part of Europe. In the 18th century, French took its place.

In the 20th century, Spanish was introduced in Equatorial Guinea and Western Sahara and parts of the United States, such as Spanish Harlem in New York City, that had not been part of the Spanish Empire.

For details on borrowed words and other external influences in Spanish, see Influences on the Spanish language.

Geographic distribution

Template:Spanish Spanish is one of the official languages of the Organization of American States, the United Nations, the South American Community of Nations, and the European Union.

With approximately 106 million first-language and second-language speakers, Mexico boasts the largest population of Spanish-speakers in the world. The three next largest Spanish-speaking populations reside in Colombia, Spain and Argentina.

Spanish is the official language in 21 countries: Argentina, Bolivia (co-official Quechua and Aymara), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea (co-official French), Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama , Paraguay (co-official Guaraní), Peru (co-official Quechua and Aymara), Puerto Rico (co-official English), Spain (co-official in some regions with Catalan, Galician and Basque), Uruguay, and Venezuela.

The vast majority of its speakers are located in Spain and the Western Hemisphere.

The non-Spanish speaking Americas

Spanish holds no official recognition in the former British colony of Belize. However, it is the native tongue of about 40% of the population, and is spoken as a second language by another 15%.[10] It is mainly spoken by Hispanic descendants who have remained in the region since the 17th century. However, English remains the sole official language.[11]

Spanish has become increasingly important in Brazil due to proximity and increased trade with its Spanish-speaking neighbors (for example, as a member of the Mercosur trading bloc).[12] In 2005, the National Congress of Brazil approved a bill, signed into law by the President, that makes Spanish available as a foreign language in the country's secondary schools.[13] In many border towns and villages (especially along the Uruguayan-Brazilian border) a mixed language commonly known as Portunhol is also spoken.[14]

In the United States, 42.7 Million people are Hispanics according to the 2005 census. Some 32 million people (12% of the whole population) aged 5 years or older speak Spanish at home.[15] While this may be due to immigration, Spanish is also the most widely taught foreign language.[16] In total, the U.S. contains the world's fifth-largest Spanish speaking population.[17]

Europe

Spanish is an official language of the European Union. In European countries other than Spain, it is spoken in communities in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, and an important language of business communication for those countries as well.[18][19] It is also spoken widely in Gibraltar, although English is used for official purposes.[20] Spanish also shares a strong lexical similarity with its sister Romance languages of Italian and Portuguese, and may be mutually intelligible on a small scale with those languages within Italy and Portugal.[21]

Asia

Japanese Peruvians in Japan

Spanish is spoken by about 50,000 Japanese Peruvian expatriates living in Japan.[22] Spanish is also spoken by small percentages of Hispanic expatriates living in the Middle East.Template:Fact

The Philippines

Although Spanish was the official language of the Philippines for over four centuries, its importance fell in the first half of the 20th century following the US occupation and administration of the islands. The introduction of the English language in the Filipino government system put an end to use of Spanish as the official language. The language lost its status in 1987, during the Corazon Aquino administration.

According to the 1990 census, there were 2,658 native speakers of Spanish [23]. The number of Spanish speakers, however, are not available in the ensuing 1995 and 2000 censuses.

Additionally, according to the 2000 census, there are over 600,000 native speakers of Chavacano, a Spanish based creole spoken in Cavite and Zamboanga.

Many Philippine languages have numerous Spanish loanwords.

Africa

In Africa, Spanish is spoken in Canary Islands, Ceuta and Melilla which are part of Spain. It is co-official with French in Equatorial Guinea, a small country of 500 000 people where it is the prevalent language.

Oceania

Template:Unreferenced Among the countries and territories in Oceania, Spanish is also spoken by 3,000 inhabitants of Easter Island, a territorial possession of Chile. The language is also spoken in Australia Template:Fact mainly by expatriate Hispanic communities living mainly in Sydney. Template:Fact

The island nations of Guam, Palau, Northern Marianas, Marshall Islands and Federated States of Micronesia all once had Spanish speakers, but Spanish has long since been forgotten. It now only exists as an influence on the local native languages.

Antarctica

In Antarctica, the territorial claims and permanent bases made by Argentina and Chile also place Spanish as the official and working language of these exclaves. Template:Fact

Total numbers of Spanish speakers

- The following is a list of the numbers of estimated Spanish speakers in different regions of the Hispanic world.

| Country | Speakers | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mexico | 106,255,000 |

| 2 | Colombia | 46,500,000 |

| 3 | Spain | 44,000,000 |

| 4 | Argentina | 41,248,000 |

| 5 | United States of America | 32,200,000(a) |

| 6 | Venezuela | 26,021,000 |

| 7 | Peru | 23,191,000 |

| 8 | Chile | 15,795,000 |

| 9 | Cuba | 11,285,000 |

| 10 | Ecuador | 10,946,000 |

| 11 | Dominican Republic | 8,850,000 |

| 12 | Guatemala | 8,163,000 |

| 13 | Honduras | 7,267,000 |

| 14 | Bolivia | 7,010,000 |

| 15 | El Salvador | 6,859,000 |

| 16 | Nicaragua | 5,503,000 |

| 17 | Paraguay | 4,737,000 |

| 18 | Costa Rica | 4,220,000 |

| 19 | Puerto Rico | 4,017,000 |

| 20 | Uruguay | 3,442,000 |

| 21 | Panama | 3,108,000 |

| 22 | Equatorial Guinea | 447,000 |

| 23 | Canada | 245,000[24] |

| 24 | Belize | 130,000 |

| 25 | Philippines | < 3,000 |

(a) Only includes people 5 years of age and older[15]

Variations

There are important variations among the regions of Spain and throughout Spanish-speaking America. In Spain the Castilian dialect pronunciation is commonly taken as the national standard (although the characteristic weak pronouns usage or laísmo of this dialect is deprecated). One has to be aware that for most people, nearly for everyone in Spain, "standard Spanish" means "pronouncing everything exactly as it is written", which of course doesn't correspond to any real dialect. In practice, the standard way of speaking Spanish in the media is "written Spanish" for formal speech, "Madrilenian dialect" (basically a southern dialect) for informal speech.

Spanish has three second-person singular pronouns: tú, usted, and in some parts of Latin America, vos (the use of this form is called voseo). Generally speaking, tú and vos are informal and used with friends (though in Spain vos is considered an archaic form for address of exalted personages, its use now mainly confined to the liturgy). Usted is universally regarded as the formal form (derived from vuestra merced, "your mercy") , and is used as a mark of respect, as when addressing one's elders or strangers. The pronoun vosotros is the plural form of tú in most of Spain, although in the Americas (and certain southern Spanish cities such as Cádiz, and in the Canary Islands) it is replaced with ustedes. It is remarkable that the use of ustedes for the informal plural "you" in southern Spain does not follow the usual rule for pronoun-verb agreement; e.g., while the formal form for "you go", ustedes van, uses the third-person plural form of the verb, in Cádiz the informal form is constructed as ustedes vais, using the second-person plural of the verb. In the Canary Islands, though, the usual pronoun-verb agreement is preserved in most cases.

Vos (see Voseo) is used extensively as the primary spoken form of the second-person singular pronoun in many countries of Latin America, including Argentina, Costa Rica, EcuadorTemplate:Fact, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Uruguay, the Antioquia and Valle del Cauca states of Colombia and the State of Zulia in Venezuela. In Argentina, Uruguay, and increasingly in Paraguay, it is also the standard form used in the media, but media in other voseante countries generally continue to use usted or tú except in advertisements, for instance. Vos may also be used regionally in other countries. Depending on country or region, usage may be considered standard or (by better educated speakers) to be unrefined. Interpersonal situations in which the use of vos is acceptable may also differ considerably between regions.

Spanish forms also differ regarding second-person plural pronouns. The Spanish dialects of Latin America have only one form of the second-person plural, ustedes (formal or familiar, as the case may be). In Spain there are two forms — ustedes (formal) and vosotros (familiar).

The Real Academia Española (Royal Spanish Academy), like academies formed for twenty-one other national languages, exercises a standardizing influence through its publication of dictionaries and widely respected grammar and style guides. Due to this influence and for other sociohistorical reasons, a standardized form of the language (Standard Spanish) is widely acknowledged for use in literature, academic contexts and the media.

Some words can be different, even embarrassingly so, in different Hispanophone countries. Most Spanish speakers can recognize other Spanish forms, even in places where they are not commonly used, but Spaniards generally do not recognise specifically American usages. For example, Spanish mantequilla, aguacate and albaricoque (respectively, "butter", "avocado", "apricot") correspond to manteca, palta, and damasco, respectively, in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay. The everyday Spanish words coger (to catch, get, or pick up), pisar (to step on) and concha (seashell) are considered extremely rude in parts of Latin America, where the meaning of coger and pisar is also "to have sex" and concha means "vagina". The Puerto Rican word for "bobby pin" (pinche) is an obscenity in Mexico, and in Nicaragua simply means stingy. Other examples include taco, which means "swearword" in Spain but is known to the rest of the world as the Mexican foodstuff. Pija in many countries of Latin America is a slang and informal word for penis, while in Spain the word signifies "posh girl" or "snobby". Coche, which means car in Spain, means pig in GuatemalaTemplate:Fact while carro means "car" in some Latin American countries and "cart" in others as well as in Spain.

Writing system

Spanish is written using the Latin alphabet, with the addition of the character "ñ" (eñe), an "n" with tilde. Historically, the digraphs "ch" (che), "ll" (elle), and "rr" (erre doble, double "r") were regarded as single letters, with their own names and places in the alphabet (a, b, c, ch, d…, l, ll, m, n, ñ, o… r, rr, s…), because each represents a single phoneme (/tʃ/, /ʎ/, and /r/, respectively). Since 1994, these letters are to be replaced with the appropriate letter pair in collation. Spelling remains visually unchanged, but words with "ch" are now alphabetically sorted between those with "ce" and "ci", instead of following "cz", and similarly for "ll" and "rr". However, the names che, elle and erre doble are still used colloquially.

Excluding a very small number of regional terms such as México, pronunciation can be entirely determined from spelling (see Mexico: Origin and history of the name). A typical Spanish word is stressed on the syllable before the last if it ends with a vowel (not including "y") or with a vowel followed by "n" or "s", and stressed on the last syllable otherwise. Exceptions to this rule are indicated by placing an acute accent on the stressed vowel.

The acute accent is additionally used to distinguish certain homophones, especially when one of them is a stressed word and the other one is a clitic: compare el ("the" before a masculine singular noun) with él ("he" or "it"), or té ("tea"), dé ("give") and sé ("I know", or imperative "be") with te ("you", object pronoun), de (preposition "of" or "from"), and se (reflexive pronoun). Interrogative pronouns (que, cual, donde, quien, etc.) receive accents in direct or indirect questions, and some demonstratives (ese, este, aquel, etc.) are accented when used as pronouns. The conjunction o ("or") is written with an accent between numerals so as not to be confused with a zero: e.g., 10 ó 20 should be read as diez o veinte rather than diez mil veinte ("10, 020"). Accent marks are frequently omitted in capital letters, though this is not standard.

Interrogative and exclamatory clauses are introduced with inverted question ( ¿ ) and exclamation marks ( ¡ ).

Sounds

The phonemic inventory listed in the following table includes historical phonemes that have merged with others in the process of the language's evolution (in most dialects), marked with an asterisk (*). Sounds in parentheses are allophones or dialectal variants.

| Bilabial | Labio- Dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | (ɱ) | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |||||||

| Plosives | p | b | t | d | k | g | ||||||

| Fricatives | f | θ* | ṣ | (z) | ʝ | x | (h) | |||||

| Affricate | tʃ | |||||||||||

| Approximants | (β̞) | (ð̞) | (ɰ) | |||||||||

| Laterals | l | ʎ* | ||||||||||

| Flaps | ɾ | |||||||||||

| Trills | r | |||||||||||

By the 16th century, the consonant system of Spanish underwent the following important changes that differentiated it from neighboring Romance languages such as Portuguese and Catalan:

- The initial /f/, that had evolved into a vacillating /h/, was lost in most words (although this etymological h- has been preserved in spelling and in some Andalusian dialects is still aspirated).

- The bilabial approximant /β̞/ (which was written u or v) merged with the bilabial oclusive /b/ (written b). Orthographically, b and v do not correspond to different phonemes in contemporary Spanish, excepting some areas in Spain, particularly the ones influenced by Catalan.

- The voiced alveolar fricative /z/ (written as s between vowels) merged with voiceless /s/ (written s, or ss between vowels).

- The voiced alveolar affricate /dz/ (written z) merged with voiceless /ts/ (written ç, or c before e, i), and then /ts/ developed into the interdental /θ/, now written z, or c before e, i. But in Andalusia, the Canary Islands and the Americas this sound merged with /s/ as well. (Notice that the ç or c with cedilla was in its origin a Spanish letter, although it is no longer used.)

- The voiced postalveolar fricative /ʒ/ (written j, or g before e, i) merged with voiceless /ʃ/ (written x, as in Quixote), and then /ʃ/ evolved into the modern velar sound /x/ by the 17th century, now written with j, or g before e, i. Nevertheless, in most parts of Argentina and in Uruguay, y and ll have both evolved to /ʒ/ or /ʃ/.

The consonant system of Medieval Spanish has been better preserved in Ladino and in Portuguese, neither of which underwent these shifts.

Lexical stress

Spanish has a phonemic stress system — stress is not fixed, and different stress patterns can result in separate meanings for one and the same word. Spanish makes abundant use of this feature, especially in distinguishing verb conjugation forms. For example, the word camino (with penultimate stress) means "road" or "I walk" whereas caminó (with final stress) means "you (formal)/he/she/it walked". Another example is the word práctico (first-syllable stress) "practical", which is different from practico (second-syllable stress) "I practice," and practicó (last-syllable stress) "you (formal)/he/she/it practiced." Also, since Spanish syllables are all pronounced at a more or less constant tempo, the language is said to be syllable-timed.

As mentioned above, stress can always be predicted from the written form of a word. An amusing example of the significance of stress and intonation in Spanish is the riddle como como como como como como, to be punctuated and accented so that it makes sense. The answer is ¿Cómo, cómo como? ¡Como como como! ("What do you mean / how / do I eat? / I eat / the way / I eat!").

Grammar

Spanish is a relatively inflected language, with a two-gender system and about fifty conjugated forms per verb, but small noun declension and limited pronominal declension. (For a detailed overview of verbs, see Spanish verbs and Spanish irregular verbs.)

Spanish syntax is generally Subject Verb Object, though variations are common. Spanish is right-branching, uses prepositions, and usually places adjectives after nouns.

Spanish is also pro-drop (allows the deletion of pronouns when pragmatically unnecessary) and verb-framed.

See also

- Romance languages

- Real Academia Española

- Common phrases in Spanish

- Hispanophone

- List of English words of Spanish origin

- Names given to the Spanish language

- Spanish proverbs

- Spanish language poets

- Spanish-based creole languages

- Spanish profanity

- Portuguese Language

- Portuñol

- Papiamento, Chavacano language, Palenquero

- Llanito

- Rock en español (Spanish language rock and roll)

- Latin Union

- Isleños

- Spanish Empire

- Frespañol

- Spanglish

Local varieties

Template:Col-start Template:Col-2

- Andalusian Spanish

- Argentine Spanish

- Bolivian Spanish

- Caliche

- Central American Spanish

- Chilean Spanish

- Colombian Spanish

- Cuban Spanish

- Dominican Spanish

- Mexican Spanish

- Peruvian Coast Spanish

- Puerto Rican Spanish

- Rioplatense Spanish

- Spanish in the Philippines

- Spanish in the United States

- Venezuelan Spanish

|}

References

- ↑ Fuentes y criterios demográficos. Centro virtual Cervantes.

- ↑ Languages Spoken By More Than 10 Million People, MSN Encarta, Summer Institute of Linguistics (see the ranking).

- ↑ Ethnologue, 2005 Edition.

- ↑ international.tamu.edu/ssp/InfoSheets/Mexico.pdf

- ↑ Template:Citeweb

- ↑ ¿Por qué español? (Spanish). Universpain.

- ↑ Template:PDFlink, Statistical Abstract of the United States: page 47: Table 47: Languages Spoken at Home by Language: 2003

- ↑ Template:PDFlink, MLA Fall 2002.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Spanish. ethnologue.

- ↑ Belize Population and Housing Census 2000

- ↑ CIA World Factbook - Belize

- ↑ MERCOSUL, Portal Oficial (Portuguese)

- ↑ BrazilMag.com, August 08 2005.

- ↑ Lipski, John M. (2006). Too close for comfort? the genesis of “portuñol/portunhol”. Selected Proceedings of the 8th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. ed. Timothy L. Face and Carol A. Klee, 1-22. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 U.S. Census Bureau. Percent of People 5 Years and Over Who Speak Spanish at Home: 2005

- ↑ Template:PDFlink, MLA Fall 2002.

- ↑ Facts, Figures, and Statistics About Spanish, American Demographics, 1998.

- ↑ BBC Education - Languages, Languages Across Europe - Spanish.

- ↑ Elucidate - Business Communication Across Borders: A Study of Language Use and Practice in European Companies Edited by Professor S Hagen © InterAct International, 1997 ]

- ↑ CIA World Factbook - Gibraltar

- ↑ Ethnologue Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/.

- ↑ Asia Times. Home; is where the heartbreak is for Japanese-Peruvians by Abraham Lama.

- ↑ Ethnologue. Ethnologue Report for the Philippines.

- ↑ Population by mother tongue. Statistics Canada.

External links

- Ethnologue report for Spanish

- Spanish evolution from Latin

- Template:Es icon Dictionary of the RAE Real Academia Española's official Spanish language dictionary

- Spanish phrasebook on WikiTravel

- The Project Gutenberg EBook of A First Spanish Reader by Erwin W. Roessler and Alfred Remy.