William Howard Taft: Difference between revisions

imported>Derek Harkness m (Remove redundant images) |

imported>Richard Jensen (add cartoons) |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

==Presidency 1909-1913== | ==Presidency 1909-1913== | ||

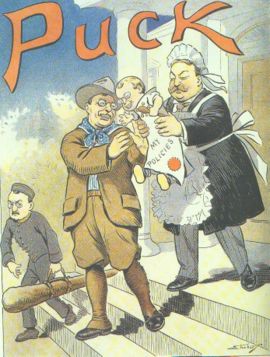

[[Image:1909.jpg|thumb|270px]] | |||

===Policies=== | ===Policies=== | ||

After serving for nearly two full terms, the popular [[Theodore Roosevelt]] refused to run in [[U.S. presidential election, 1908|the election of 1908]]. Roosevelt certified Taft as a genuine "progressive", in [[U.S. presidential election, 1908|1908]], pushing through the nomination of his Secretary of War for the presidency. At the age 51 Taft easily defeated three-time candidate [[William Jennings Bryan]]. Taft considered himself a "progressive" because of his deep belief in "The Law" as the scientific device that should be used by judges to solve society's problems. Taft proved a less adroit politician than Roosevelt and seemed to lack the energy and personal magnetism of his mentor, not to mention the publicity devices, the dedicated supporters, and the broad base of public support that made Roosevelt so formidable. When Roosevelt realized that lowering the tariff would risk severe tensions inside the Republican Party, pitting producers (manufacturers and farmers) against department stores and consumers, he stopped talking about the issue. Taft ignored the risks and tackled the tariff boldly, on the one hand encouraging reformers to fight for lower rates, then cutting deals with conservative leaders that kept overall rates high. The resulting [[Payne-Aldrich tariff]] of 1909 was too high for most reformers, but instead of blaming this on Senator [[Nelson Aldrich]] and big business, Taft took credit, calling it the best bill to come from the Republican Party. Again, he had managed to alienate all sides.<ref>Pringle (1939) v. 1 </ref> | After serving for nearly two full terms, the popular [[Theodore Roosevelt]] refused to run in [[U.S. presidential election, 1908|the election of 1908]]. Roosevelt certified Taft as a genuine "progressive", in [[U.S. presidential election, 1908|1908]], pushing through the nomination of his Secretary of War for the presidency. At the age 51 Taft easily defeated three-time candidate [[William Jennings Bryan]]. Taft considered himself a "progressive" because of his deep belief in "The Law" as the scientific device that should be used by judges to solve society's problems. Taft proved a less adroit politician than Roosevelt and seemed to lack the energy and personal magnetism of his mentor, not to mention the publicity devices, the dedicated supporters, and the broad base of public support that made Roosevelt so formidable. When Roosevelt realized that lowering the tariff would risk severe tensions inside the Republican Party, pitting producers (manufacturers and farmers) against department stores and consumers, he stopped talking about the issue. Taft ignored the risks and tackled the tariff boldly, on the one hand encouraging reformers to fight for lower rates, then cutting deals with conservative leaders that kept overall rates high. The resulting [[Payne-Aldrich tariff]] of 1909 was too high for most reformers, but instead of blaming this on Senator [[Nelson Aldrich]] and big business, Taft took credit, calling it the best bill to come from the Republican Party. Again, he had managed to alienate all sides.<ref>Pringle (1939) v. 1 </ref> | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

===Party schism=== | ===Party schism=== | ||

Despite his obvious achievements, progressives decried Taft's acceptance of the ''[[Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act]]'', which lowered the tariff on the farm products of the western states, whose citizens desired lower rates on Eastern factory products. Taft opposed to the entry of the state of [[Arizona]] into the Union because of its judicial features. Progressives grumbled that he worked too closely with conservative Senator [[Nelson W. Aldrich]] and Speaker of the House [[Joseph G. Cannon]]. By 1910, Taft's party was deeply divided between progressives and conservatives. | Despite his obvious achievements, progressives decried Taft's acceptance of the ''[[Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act]]'', which lowered the tariff on the farm products of the western states, whose citizens desired lower rates on Eastern factory products. Taft opposed to the entry of the state of [[Arizona]] into the Union because of its judicial features. Progressives grumbled that he worked too closely with conservative Senator [[Nelson W. Aldrich]] and Speaker of the House [[Joseph G. Cannon]]. By 1910, Taft's party was deeply divided between progressives and conservatives. | ||

[[Image:1912GOP.JPG|thumb|250px|Taft forces defeated Roosevelt and controlled the convention]] | |||

On his return from Europe, Roosevelt broke with Taft in one of the most dramatic political feuds of the 20th century. To the surprise of observers who thought Roosevelt had unstoppable momentum, Taft outmaneuvered Roosevelt and LaFollette, seized control of the GOP, and forced both out of the party. The main issue in 1911-12 was independence of the judiciary, which Roosevelt denounced. Most lawyers in the GOP supported Taft, including many of Roosevelt's key supporters like [[Elihu Root]], [[Henry Stimson]], and Roosevelt's own son-in-law, [[Nicholas Longworth]]. In lining up delegates for the 1912 nomination, Taft outmaneuvered Roosevelt, who had started much too late, and kept control of the Republican party. | On his return from Europe, Roosevelt broke with Taft in one of the most dramatic political feuds of the 20th century. To the surprise of observers who thought Roosevelt had unstoppable momentum, Taft outmaneuvered Roosevelt and LaFollette, seized control of the GOP, and forced both out of the party. The main issue in 1911-12 was independence of the judiciary, which Roosevelt denounced. Most lawyers in the GOP supported Taft, including many of Roosevelt's key supporters like [[Elihu Root]], [[Henry Stimson]], and Roosevelt's own son-in-law, [[Nicholas Longworth]]. In lining up delegates for the 1912 nomination, Taft outmaneuvered Roosevelt, who had started much too late, and kept control of the Republican party. | ||

1912 was the first year that some delegates were determined through primary elections. Primary elections were seen as a way to take power away from party bosses and put it in the hands of the people. Out of the 14 Republican primaries held, Roosevelt won 9, and Taft only won 3. Robert Lafollete won the other 2. Nevertheless, Taft had the delegates and won the nomination at the republican nominating convention in Chicago. | 1912 was the first year that some delegates were determined through primary elections. Primary elections were seen as a way to take power away from party bosses and put it in the hands of the people. Out of the 14 Republican primaries held, Roosevelt won 9, and Taft only won 3. Robert Lafollete won the other 2. Nevertheless, Taft had the delegates and won the nomination at the republican nominating convention in Chicago. | ||

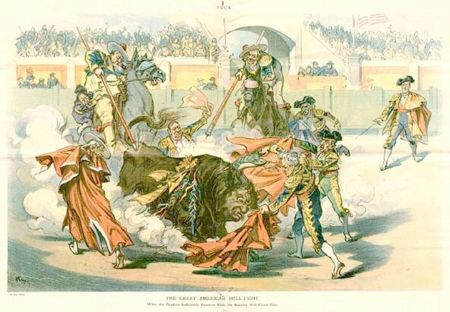

[[Image:1912fight.jpg|thumb|450px|TR (the bull) is attacked from all sides; Taft on horseback at left; ''Puck'' magazine]] | |||

Instead, Roosevelt was forced to create the [[Progressive Party (United States, 1912)|Progressive Party]] (or "Bull Moose") ticket, splitting the Republican vote in the 1912 election. [[Woodrow Wilson]], the Democrat, was elected, although many historians argue that Wilson would have won anyway, because the Republican factions would not support each other. Taft won a mere eight electoral votes, making it the single worst defeat for a President seeking re-election. He achieved his main goal, however, keeping permanent control of the party and making the courts sacrosanct. | Instead, Roosevelt was forced to create the [[Progressive Party (United States, 1912)|Progressive Party]] (or "Bull Moose") ticket, splitting the Republican vote in the 1912 election. [[Woodrow Wilson]], the Democrat, was elected, although many historians argue that Wilson would have won anyway, because the Republican factions would not support each other. Taft won a mere eight electoral votes, making it the single worst defeat for a President seeking re-election. He achieved his main goal, however, keeping permanent control of the party and making the courts sacrosanct. | ||

[[Image:FORCE.JPG|thumb|350px|left|Taft proved immovable. ''Puck'' cartoon 1912]] | |||

===Supreme Court Appointments=== | ===Supreme Court Appointments=== | ||

During his presidency, Taft appointed six Justices to the [[Supreme Court of the United States]]: [[Horace Harmon Lurton]] in 1910; [[Charles Evans Hughes]] in 1910; [[Edward Douglass White]] as Chief Justice in 1910; [[Willis Van Devanter]] in 1911; [[Joseph Rucker Lamar]] in 1911; and [[Mahlon Pitney]] in 1912 | During his presidency, Taft appointed six Justices to the [[Supreme Court of the United States]]: [[Horace Harmon Lurton]] in 1910; [[Charles Evans Hughes]] in 1910; [[Edward Douglass White]] as Chief Justice in 1910; [[Willis Van Devanter]] in 1911; [[Joseph Rucker Lamar]] in 1911; and [[Mahlon Pitney]] in 1912 | ||

Revision as of 15:47, 5 June 2007

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857 – March 8, 1930) was an American politician, the 27th President of the United States, the 10th Chief Justice of the United States, a leader of the conservative half of the progressive wing of the Republican Party in the early 20th century, a pioneer in international arbitration and staunch advocate of world peace verging on pacifism, and scion of the leading political family in Ohio.

Taft served as Solicitor General of the United States, a federal judge, Governor-General of the Philippines, and Secretary of War before being nominated for President by the 1908 Republican National Convention with the critical backing of the incumbent President and Taft's close friend Theodore Roosevelt.

His presidency was characterized by raising the tariff, breaking up large monopolies, and promoting world peace. He failed in a new tariff program with Canada. In politics the GOP was splitting in half, and Taft, in the middle, finally joined the conservative camp; Roosevelt broke with him in 1911, charging Taft was too reactionary. Taft and the conservatives were alarmed at Roosevelt's attacks on the judiciary, and took control of the party machinery. Taft defeated Roosevelt for the Republican nomination in a bruising battle in 1912 that forced Roosevelt out of the GOP and left Taft people in charge for decades. During World War I he helped set national labor policy that reduced strikes and generated union support for the national cause. In 1921, he became Chief Justice. As President and Chief Justice he helped make the federal courts, especially the Supreme Court, much more powerful in shaping national policy.

Early life

Taft was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the third of five children. His mother, Louisa Torrey, was a graduate of Mount Holyoke College. His father, Alphonso Taft, came to Cincinnati in 1839 to open a law practice. Alphonso Taft was a prominent Republican and served as Secretary of War under President Ulysses S. Grant.

Taft was brought up in the Unitarian church and remained a faithful Unitarian his entire life. At age 18, he met his future wife, Helen Herron, in Cincinnati; she and Taft courted while he was away at college. The William Howard Taft National Historic Site is the Taft boyhood home. The house in which he was born has been restored to its original appearance. It includes four period rooms which reflect the family life during Taft's boyhood. The home also includes second floor exhibits highlighting Taft's life and career, as well as an educational center.[1]

Education

In 1874, Taft attended Woodward High School. Like most of his family, he attended Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut. At Yale, he was a member of the Linonian Society, a literary and debate society; Skull and Bones, the secret society co-founded by his father in 1832; and the Beta chapter of the Psi Upsilon fraternity. In 1878, Taft graduated from Yale, ranking second in his class out of 121. He then attended Cincinnati Law School, graduating with a Bachelor of Laws in 1880. While in law school, he worked on the area newspaper The Cincinnati Commercial.[2]

Career

After admission to the Ohio bar, Taft was appointed Assistant Prosecutor of Hamilton County, Ohio, based in Cincinnati. In 1882, he was appointed local Collector of Internal Revenue. People who disagreed with Taft's beliefs and opposed the decisions he made called him a “trust buster”. Taft married his longtime sweetheart, Helen Herron, in Cincinnati in 1886. In 1887, he was appointed as a judge of the Ohio Superior Court. In 1890, President Benjamin Harrison appointed him Solicitor General of the United States. In 1892 Harrison appointed him to the newly created Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, a post which he held until 1900. It was then that he met Theodore Roosevelt for the first time.[3]

In addition to his judgeship, between 1896 and 1900 Taft also served as the first Dean and a Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Cincinnati. Eventually, he became the Chief Judge of the Sixth Circuit. One of Taft's most famous opinions was in Addyston Pipe and Steel Company v. United States (1898).[4]

In 1900, President William McKinley appointed Taft as the chairman of a commission to organize a civilian government in the Philippines, which had been ceded to the United States by Spain following the Spanish-American War and the 1898 Treaty of Paris. Although Taft initially had been opposed to the annexation of the islands and told McKinley that his real ambition was to become a justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, he reluctantly accepted the appointment when McKinley suggested that he would be "the better judge for this experience."

From 1901 to 1903, Taft served as the first civilian Governor-General of the Philippines, a position in which he was very popular among both Americans and Filipinos. For example, in 1902 Taft visited Rome to negotiate with Pope Leo XIII for the purchase of lands in the Philippines owned by the Roman Catholic Church. Taft then induced Congress to appropriate $7,239,000 to purchase the lands, which he sold to Filipinos on easy terms. In 1903, President Roosevelt offered Taft the seat on the Supreme Court to which he had for so long aspired, but he reluctantly declined when native Filipino groups begged him to remain in Manila as Governor-General.[5]

Secretary of War, 1904-1908

In 1904, Roosevelt appointed Taft as Secretary of War. Roosevelt made the basic policy decisions regarding military affairs, using Taft as a well-traveled spokesman who campaigned for Roosevelt's re-election in 1904. Taft met with the Emperor of Japan, who alerted him of the probability of war with Russia. In 1906, Roosevelt sent troops to restore order in Cuba during the revolt led by General Enrique Loynaz del Castillo, and Taft temporarily became the Civil Governor of Cuba, personally negotiating with General Castillo for a peaceful end to the revolt. In 1907, Secretary Taft helped supervise the beginning of construction on the Panama Canal. Taft repeatedly had told Roosevelt he wanted to be Chief Justice, not President (and not an associate justice), but there was no vacancy and Roosevelt had other plans. He gave Taft more responsibilities in addition to the Philippines and the Panama Canal. For a while, Taft was Acting Secretary of State. When Roosevelt was away, Taft in effect was the Acting President.[6]

Presidency 1909-1913

Policies

After serving for nearly two full terms, the popular Theodore Roosevelt refused to run in the election of 1908. Roosevelt certified Taft as a genuine "progressive", in 1908, pushing through the nomination of his Secretary of War for the presidency. At the age 51 Taft easily defeated three-time candidate William Jennings Bryan. Taft considered himself a "progressive" because of his deep belief in "The Law" as the scientific device that should be used by judges to solve society's problems. Taft proved a less adroit politician than Roosevelt and seemed to lack the energy and personal magnetism of his mentor, not to mention the publicity devices, the dedicated supporters, and the broad base of public support that made Roosevelt so formidable. When Roosevelt realized that lowering the tariff would risk severe tensions inside the Republican Party, pitting producers (manufacturers and farmers) against department stores and consumers, he stopped talking about the issue. Taft ignored the risks and tackled the tariff boldly, on the one hand encouraging reformers to fight for lower rates, then cutting deals with conservative leaders that kept overall rates high. The resulting Payne-Aldrich tariff of 1909 was too high for most reformers, but instead of blaming this on Senator Nelson Aldrich and big business, Taft took credit, calling it the best bill to come from the Republican Party. Again, he had managed to alienate all sides.[7]

Unlike Roosevelt, Taft never attacked business or businessmen in his rhetoric. However, he was attentive to the law, so he launched 90 antitrust suits, including one against the country's largest corporation, U.S. Steel, for an acquisition which Roosevelt personally had approved. As a result, Taft lost the support of antitrust reformers (who disliked his conservative rhetoric), of big business (which disliked his actions), and of Roosevelt, who felt humiliated by his protégé. Progressives within the Republican party began agitating against Taft. Senator Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin created the National Progressive Republican League to replace Taft at the national level; his campaign crashed after a disastrous speech. Most of LaFollette's supporters went over to Roosevelt, leaving LaFollette embittered and alone. More trouble came when Taft fired Gifford Pinchot, a leading conservationist and close ally of Roosevelt. Pinchot alleged that Taft's Secretary of Interior Richard Ballinger was in league with big timber interests. Conservationists sided with Pinchot, and Taft alienated yet another vocal constituency.

Taft fought for the prosecution of trusts (eventually issuing 80 lawsuits), further strengthened the Interstate Commerce Commission, established a postal savings bank and a parcel post system, and expanded the civil service. He supported the 16th Amendment by Senator Nelson Aldrich, which allowed for a federal income tax, and the 17th Amendment, mandating the direct election of senators by the people, replacing the previous system whereby they were selected by state legislatures.

Foreign policy

Taft actively pursued what he termed "dollar diplomacy" to further the economic development of less-developed nations of Latin America and Asia through American investment in their infrastructures. Throughout the early part of his presidency, Taft had difficulties with Nicaragua. When the United States shifted its interests to Panama for the purpose of building a canal, Nicaraguan President José Santos Zelaya negotiated with Germany and Japan in an unsuccessful effort to have a canal constructed in his state. The Zelaya administration had growing friction with the United States government, which started giving aid to his Conservative opponents in Nicaragua. In 1907, U.S. warships seized several of Nicaragua's seaports. In early December, United States Marines landed on Nicaragua's Caribbean Sea coast. In December 1909, Zelaya resigned and left for exile in Mexico. The U.S.-sponsored conservative regime of Adolfo Díaz was installed in his place. Military invasions increased with Marine landings in 1910 and 1912. The Marines stayed in Nicaragua through 1925.

One of Taft's main goals while President was to further the idea of world peace. Given his judicial sensibilities, he believed that international arbitration was the best means to effectuate the end of war on Earth. As such, he championed several reciprocity and arbitration treaties. In 1910, he convinced congressional Democrats to support a reciprocity treaty with Canada, but the Liberal Canadian government that negotiated the treaty was turned out of office in 1911 and the treaty collapsed. In 1910 and 1911, however, he secured the ratification of arbitration treaties that he had successfully negotiated with the United Kingdom and France and thereafter was known as one of the foremost advocates of world peace and arbitration.

16th Amendment

To solve one impasse during the 1909 tariff debate, Taft proposed income taxes for corporations and business. His new tax on corporate net income was 1% on net profits over $5,000. Legally, it was designated an excise on the privilege of doing business and not a tax on incomes as such. In 1911, the Supreme Court, in Flint v. Stone Tracy Company, approved it. Receipts grew from $21 million in the fiscal year 1910 to $34.8 million in 1912. An income tax on individuals, (unlike the tax on corporations) required a constitutional amendment. One was passed with little controversy in July, 1909, unanimously in the Senate and by a vote of 318 to 14 in the House. It quickly was ratified by the states, and in February, 1913, it became a part of the Constitution as the Sixteenth Amendment, as Taft was leaving office.

Party schism

Despite his obvious achievements, progressives decried Taft's acceptance of the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act, which lowered the tariff on the farm products of the western states, whose citizens desired lower rates on Eastern factory products. Taft opposed to the entry of the state of Arizona into the Union because of its judicial features. Progressives grumbled that he worked too closely with conservative Senator Nelson W. Aldrich and Speaker of the House Joseph G. Cannon. By 1910, Taft's party was deeply divided between progressives and conservatives.

On his return from Europe, Roosevelt broke with Taft in one of the most dramatic political feuds of the 20th century. To the surprise of observers who thought Roosevelt had unstoppable momentum, Taft outmaneuvered Roosevelt and LaFollette, seized control of the GOP, and forced both out of the party. The main issue in 1911-12 was independence of the judiciary, which Roosevelt denounced. Most lawyers in the GOP supported Taft, including many of Roosevelt's key supporters like Elihu Root, Henry Stimson, and Roosevelt's own son-in-law, Nicholas Longworth. In lining up delegates for the 1912 nomination, Taft outmaneuvered Roosevelt, who had started much too late, and kept control of the Republican party.

1912 was the first year that some delegates were determined through primary elections. Primary elections were seen as a way to take power away from party bosses and put it in the hands of the people. Out of the 14 Republican primaries held, Roosevelt won 9, and Taft only won 3. Robert Lafollete won the other 2. Nevertheless, Taft had the delegates and won the nomination at the republican nominating convention in Chicago.

Instead, Roosevelt was forced to create the Progressive Party (or "Bull Moose") ticket, splitting the Republican vote in the 1912 election. Woodrow Wilson, the Democrat, was elected, although many historians argue that Wilson would have won anyway, because the Republican factions would not support each other. Taft won a mere eight electoral votes, making it the single worst defeat for a President seeking re-election. He achieved his main goal, however, keeping permanent control of the party and making the courts sacrosanct.

Supreme Court Appointments

During his presidency, Taft appointed six Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States: Horace Harmon Lurton in 1910; Charles Evans Hughes in 1910; Edward Douglass White as Chief Justice in 1910; Willis Van Devanter in 1911; Joseph Rucker Lamar in 1911; and Mahlon Pitney in 1912

Post-presidency

Upon leaving the White House in 1913, Taft was appointed Kent Professor of Constitutional Law at Yale Law School. The same year, he was elected president of the American Bar Association. He spent much of his time writing newspaper articles and books, most notably his series on American legal philosophy. He was a vigorous opponent of prohibition in the United States. He also continued to advocate world peace through international arbitration, urging nations to enter into arbitration treaties with each other and promoting the idea of a League of Nations even before the First World War began.

When World War I did break out in Europe in 1914, however, Taft founded the League to Enforce Peace. He was co-chair of the powerful National War Labor Board between 1917 and 1918. Although he continually advocated peace, he strongly favored conscription once the United States entered the conflict, pleading publicly that the United States not fight a "finicky" war. He feared the war would be long, but was for fighting it out to a finish, given what he viewed as "Germany's brutality."

Chief Justice

In 1921, when Chief Justice Edward Douglass White died, President Warren G. Harding nominated Taft to take his place, thereby fulfilling Taft's lifelong ambition to become Chief Justice of the United States. Virtually no opposition existed to the nomination, and the Senate unanimously confirmed Taft by voice vote. He readily took up the position, serving until 1930. As such, he became the only President to serve as Chief Justice, and thus is also the only former President to swear in subsequent Presidents, giving the oath of office to both Calvin Coolidge (in 1925) and Herbert Hoover (in 1929). He remains the only person to have led both the Executive and Judicial branches of the United States government.

In 1922, Taft traveled to England to study the procedural structure of the English courts and learn how they disposed of such a large number of cases in such an expeditious manner. During the trip, King George V and Queen Mary received Taft and his wife as state visitors. With what he had learned in England, Taft advocated passage of the Judiciary Act of 1925 (often called the "Judges Bill"), which shifted the Supreme Court's appellate jurisdiction to be excersisable solely on review by writ of certiorari, thereby empowering the Supreme Court to give preference to cases of national importance and allowing the Court to work more efficiently. Taft was also the first Justice to employ two full time law clerks.

In 1929, Taft successfully argued for the construction of the Supreme Court Building, reasoning that the Court needed to distance itself from Congress as a separate branch of government. Until then, the Court had heard cases in a designated room in the basement of the Capitol. Taft, however, did not live to see the building's completion in 1935.

While Chief Justice, Taft wrote the opinion for the Court in 256 cases out of the Court's ever-growing caseload. His philosophy of constitutional interpretation was essentially historical contextualism. Some of his more notable opinions include:

- Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co., (opinion for the Court)

- Holding the 1919 Child Labor Tax Law unconstitutional.

- Balzac v. Porto Rico, (opinion for the Court)

- Ruling that the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply the criminal provisions of the Bill of Rights to overseas territories. This was one of the more famous of the "Insular Cases."

- Adkins v. Children's Hospital, (dissenting opinion)

- Disapproving of the Court upholding Lochner v. New York.

- Myers v. United States, (opinion for the Court)

- Ruling that the President of the United States had the power unilaterally to dismiss executive appointees who had been confirmed by the Senate.

- Gong Lum v. Rice, (opinion for the Court)

- Reluctantly ruling that the Fourteenth Amendment did not prohibit Mississippi's prevention of Asian children attending white schools in the midst of racial segregation.

- Olmstead v. United States, (opinion for the Court)

- Ruling that the Fourth Amendment's proscription on unreasonable search and seizure did not apply to wiretaps.

- Wisconsin v. Illinois, (opinion for the Court)

- Holding that the equitable power of the United States can be used to impose positive action on the states in a situation in which nonaction would result in damage to the interests of other states.

- Old Colony Trust Co. v. Commissioner, (opinion for the Court)

- Holding that where a third party pays the income tax due to an individual, the amount of tax paid constitutes additional income to the taxpayer.

Medical condition

Evidence from eyewitnesses and from Taft himself strongly suggests that he had severe obstructive sleep apnea during his presidency, a consequence of his 300- to 340-pound (136- to 159-kg) weight. His legendary tendency to fall asleep in almost any circumstance, an open secret and source of embarrassment for his intimates, is now understood to have been the most obvious manifestation of the disease. Within a year of leaving the Presidency, Taft lost approximately 80 pounds (32 kg). His somnolence resolved and, less obviously, his systolic blood pressure dropped 40-50 mmHg (from 210 mmHg). Undoubtedly, this weight loss extended his life.[8]

Death and legacy

Taft retired as Chief Justice on February 3, 1930, because of ill health. He was succeeded by Charles Evans Hughes, whom he had appointed to the Court while President. Taft died of heart disease on Saturday, March 8, 1930. Three days later, on March 11, he became the first president[9] to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. His grave marker was sculpted by James Earl Frazer out of Stony Creek granite.[9]

A third generation of the Taft family entered the national political stage in 1938. The former President's oldest son, Robert A. Taft I, was elected to the United States Senate from Ohio. His other son, Charles Phelps Taft II, served as mayor of Cincinnati, Ohio, from 1955 to 1957. Two more generations of the Taft family later entered politics. The President's grandson, Robert Taft Jr., served a term as a Senator from Ohio from 1971-1977; the President's great-grandson, Robert A. Taft II, served as the governor of Ohio from 1999 - 2007. William Howard Taft III was U.S. ambassador to Ireland from 1953 to 1957. William Howard Taft IV, currently in private law practice, was general counsel in the former Department of Health, Education, and Welfare in the 1970s, Deputy Secretary of Defense under Casper Weinberger and Frank Carlucci in the 1980s, and and acted as Secretary of Defense during the vacancy of January-March 1989. In addition, he was a high-level official in the United States Department of State from 2000 to 2006.

Trivia

- In religious beliefs, Taft was a Unitarian. He once remarked, "I do not believe in the divinity of Christ, and there are many other of the postulates of the orthodox creed to which I cannot subscribe."

- He became an honorary member of the Yale Chapter of the Acacia Fraternity in 1913 (while he was a professor of law at Yale).

- Taft was severely overweight to the point that he became stuck in the bathtub in the White House several times, prompting the installation of a new bathtub capable of holding all of the men who installed it, something the White House denied until the bathtub was torn out years later. At 6 feet, and weighing over 350 pounds (159 kg), Taft is the heaviest person to be President, although Jefferson, Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Bill Clinton were taller.

- When asked about his time on the Supreme Court and as President, Chief Justice Taft allegedly remarked, "I don't remember that I ever was President."

- In Manila, Philippines, Taft Avenue is named after him.

- Taft was the last American president to have had facial hair (in this case, a moustache), as of 2007.

- Taft was an avid baseball fan, but contrary to myth he did not create the seventh-inning stretch, which was custom decades earlier. He was, however, the first American president to throw the ceremonial first pitch at a baseball game, at Griffith Stadium, Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1910.

- Taft was the first American president to golf as a hobby.

- Taft was the first president to occupy the Oval Office when it was opened in October 1909.

- Taft was the first American president to own a presidential automobile. He converted the White House stables into a four-car garage in 1909.[10]

- In his youth, Taft allegedly once ate a live frog on either a dare or a bet

- Taft owned a Holstein cow, Pauline Wayne, which he let graze freely on the White House lawn. Pauline was the last cow to live at the White House. She provided milk for the president and his family.[11]

- Even though the strife during the election of 1912 devastated the once very close friendship between Taft and Theodore Roosevelt, the two reconciled not long before Roosevelt's death.

- The First District Court of Appeals in Cincinnati, Ohio, is named after him.

- William Howard Taft Road in Cincinnati, Ohio is named after him.

- He is one of two presidents buried at Arlington (the other being John F. Kennedy) and one of four chief justices buried at Arlington (the others being Earl Warren, Warren Burger, and William Rehnquist).

- He was the first Chief Justice that did not die in office since Oliver Ellsworth and was the only Chief Justice ever to have a state funeral.

- There is a law school named after him in Santa Ana, California: William Howard Taft University.[12]

- In later years, Taft owned a wooden cane that was a gift from Professor of Geology W.S. Foster, from 250,000-year-old wood.[13]

- While being governor of the Philippines, Taft one day sent a message to Washington, D.C. that read "Went on a horseride today; feeling good." Secretary of War at the time Elihu Root sent a reply message that read "How's the horse?"[1]

- There are William Howard Taft High Schools in San Antonio, Texas, Woodland Hills, California, and the Bronx, New York that are named after him.

Bibliography

Secondary sources

- Anderson, Donald F. William Howard Taft: A Conservative's Conception of the Presidency (1973)

- Anderson, Judith Icke. William Howard Taft: An Intimate History (1981).

- Anthony, Carl Sferrazza. Nellie Taft : The Unconventional First Lady of the Ragtime Era (2005)

- Bromley, Michael L. William Howard Taft and the First Motoring Presidency (2003)

- Burton, David H. Taft, Holmes, and the 1920s Court: An Appraisal (1998) online edition

- Burton, David H., Taft, Roosevelt, and the Limits of Friendship (2005)

- Burton, David H. William Howard Taft, Confident Peacemaker (2005)

- Chace, James. 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft and Debs -The Election that Changed the Country (2004)

- Coletta, Paolo Enrico. The Presidency of William Howard Taft (1973), standard survey

- Conner Valerie. The National War Labor Board' '(1983)

- Duffy, Herbert S. William Howard Taft (1930)

- Friedman, Leon, ed. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Vol 3,

- Hechler, Kenneth S. Insurgency: Personalities and Politics of the Taft Era 1940.

- Michael J. Korzi, Our chief magistrate and his powers: a reconsideration of William Howard Taft's "Whig" theory of presidential leadership (2003)

- Manners, William. TR and Will: A Friendship that Split the Republican Party 1969.

- Minger Ralph E. William Howard Taft and United States Diplomacy: The Apprenticeship Years. 1900-1908 (1975)

- Mowry George E. The Era of Theodore Roosevelt (1958) scholarly survey of era online edition

- Pringle, Henry F. The Life and Times of William Howard Taft: A Biography 2 vol (1939); Pulitzer prize; the standard biography vol 1 online

- Renstrom, Peter G. The Taft Court: Justices, Rulings and Legacy ABC-CLIO, 2003

- Scholes, Walter V. and Marie V. Scholes. The Foreign Policies of the Taft Administration 1970.

- Stanley D. Solvick. "William Howard Taft and the Payne-Aldrich Tariff," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 50, No. 3. (Dec., 1963), pp. 424-442. in JSTOR

- Wilensky, Norman N. Conservatives in the Progressive Era: The Taft Republicans of 1912 (1965).

Primary sources

- Butt, Archie. Taft and Roosevelt: The Intimate Letters of Archie Butt (1930) online edition Butt was a top aide to both presidents

- Taft, William Howard

- Liberty Under Law Yale University Press, 1922.

- Popular Government Yale University Press, 1913.

- Present Day Problems

- The Anti-Trust Act and the Supreme Court Harper and Row, 1914.

- The Collected Works of William Howard Taft. Edited by David H. Burton. Ohio University Press, 2001-. 6 of 8 volumes have appeared.

- The President and His Powers. Columbia University Press, 1924.

- Taft, Mrs. William Howard, Recollections of Full Years (1914)

External links

- Inaugural Address

- Audio clips of Taft's speeches

- Taft's sleep apnea

- Taft's medical history

- White House biography

- Presidential Biography by Stanley L. Klos

- ArlingtonCemetery.Net citing New York Times Obituary

- William Howard Taft cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- W.H. Taft Pages: Taft Humor and Anecdotes

- William Taft National Historic Site

- The Last Salute: Civil and Military Funeral, 1921-1969, CHAPTER II, Former President William Howard Taft, State Funeral, 8-11 March 1930 by B. C. Mossman and M. W. Stark

References

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/wiho

- ↑ Pringle (1939) v. 1

- ↑ Pringle (1939) v. 1

- ↑ Pringle (1939) v. 1

- ↑ Pringle (1939) v. 1

- ↑ Pringle (1939) v. 1

- ↑ Pringle (1939) v. 1

- ↑ http://www.apneos.com/taft_intro.html William Howard Taft and Sleep Apnea

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Biography of William Howard Taft, President of the United States and Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Historical Information. THE OFFICIAL WEBSITE OF ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY. Retrieved on 2007-01-04.

- ↑ http://www.infoplease.com/askeds/6-27-00askeds.html

- ↑ http://www.whitehouse.gov/president/holiday/historicalpets1/05-js.html

- ↑ http://www.taftu.edu.

- ↑ The Edmonton Journal, July 10, 1920.