Mexican-American War: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen |

imported>Richard Jensen (add outline and text) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

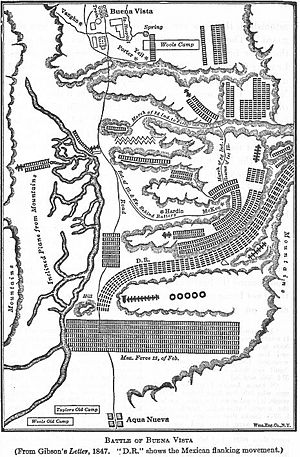

[[Image:Buena vista.jpg|thumb|300px|Battle of Buena Vista 1847]] | [[Image:Buena vista.jpg|thumb|300px|Battle of Buena Vista 1847]] | ||

==Causes== | |||

===Long-term causes=== | |||

===Perceptions of each side=== | |||

===Start of war=== | |||

Shortly after the U.S. Congress by joint resolution annexed Texas in 1845, the Mexican government recalled its minister from Washington and broke off diplomatic relations. Government newspapers in Mexico City acted as if war already existed. On June 15, 1845, Brevet Brigadier General [[Zachary Taylor]], commanding American troops in the southwest, received orders to move forward into some disputed territory "on or near the Rio Grande." In August he encamped on the west bank of the Nueces River, Texas. President Polk then sent [[John Slidell]] of New Orleans to Mexico City with a proposal to adjust the boundary dispute, and to purchase Upper California and New Mexico. | |||

Mexico was in no position to negotiate with Slidell because of its instability. In 1846 alone the presidency changed hands 4 times, the war minister changed 6 times, the finance minister changed 16 times. <ref>Donald Fithian Stevens, ''Origins of Instability in Early Republican Mexico'' (1991) p. 11 </ref> As one Mexican historian explains: <ref> Miguel E. Soto, "The Monarchist Conspiracy and the Mexican War" in ''Essays on the Mexican War'' ed by Wayne Cutler; Texas A&M University Press. 1986. pp 66-67</ref> | |||

:"Mexican public opinion and all the various political factions that aspired to or that actually shared in power at that time, had to—willingly or unwillingly—participate in a very hawkish attitude toward the war. Anyone who tried to avoid open conflict with the United States was treated as a traitor. That was precisely the case of President José Joaquin de Herrera. At one time he, at least, seriously considered receiving the American special envoy, John Slidell, in order to negotiate the problem of Texas annexation peacefully. But as soon as he assumed that position, the president was accused of favoring the handing over of a part of national territory; he was accused of treason and was overthrown." | |||

When the Mexican government refused to negotiate with Slidell, Polk on Jan. 3, 1846, instructed Taylor to advance. Within a month Taylor's forces were at the Rio Grande. On April 12 General Pedro Ampudia demanded that Taylor retreat beyond the Nueces. Taylor held his position, and on April 24 a Mexican force ambushed a party of American dragoons on the Texas side of the Rio Grande. Polk already had decided to recommend a declaration of war. On May 11 his message went to Congress. A war appropriation bill providing for enlistments passed both houses by overwhelming margins. Its preamble declared that the war existed by the act of Mexico. | |||

==Military operations 1846== | |||

==Military operations 1846== | |||

==U.S. Politics== | |||

==Peace== | ==Peace== | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

* [[Guadalupe-Hidalgo, Treaty of]] | * [[Guadalupe-Hidalgo, Treaty of]] | ||

Revision as of 21:50, 21 November 2007

The Mexican-American War (1846-48) was fought over control of Texas. Mexico lost all the battles and in the peace treaty gave up northern territories in exchange for $15 million.

Causes

Long-term causes

Perceptions of each side

Start of war

Shortly after the U.S. Congress by joint resolution annexed Texas in 1845, the Mexican government recalled its minister from Washington and broke off diplomatic relations. Government newspapers in Mexico City acted as if war already existed. On June 15, 1845, Brevet Brigadier General Zachary Taylor, commanding American troops in the southwest, received orders to move forward into some disputed territory "on or near the Rio Grande." In August he encamped on the west bank of the Nueces River, Texas. President Polk then sent John Slidell of New Orleans to Mexico City with a proposal to adjust the boundary dispute, and to purchase Upper California and New Mexico.

Mexico was in no position to negotiate with Slidell because of its instability. In 1846 alone the presidency changed hands 4 times, the war minister changed 6 times, the finance minister changed 16 times. [1] As one Mexican historian explains: [2]

- "Mexican public opinion and all the various political factions that aspired to or that actually shared in power at that time, had to—willingly or unwillingly—participate in a very hawkish attitude toward the war. Anyone who tried to avoid open conflict with the United States was treated as a traitor. That was precisely the case of President José Joaquin de Herrera. At one time he, at least, seriously considered receiving the American special envoy, John Slidell, in order to negotiate the problem of Texas annexation peacefully. But as soon as he assumed that position, the president was accused of favoring the handing over of a part of national territory; he was accused of treason and was overthrown."

When the Mexican government refused to negotiate with Slidell, Polk on Jan. 3, 1846, instructed Taylor to advance. Within a month Taylor's forces were at the Rio Grande. On April 12 General Pedro Ampudia demanded that Taylor retreat beyond the Nueces. Taylor held his position, and on April 24 a Mexican force ambushed a party of American dragoons on the Texas side of the Rio Grande. Polk already had decided to recommend a declaration of war. On May 11 his message went to Congress. A war appropriation bill providing for enlistments passed both houses by overwhelming margins. Its preamble declared that the war existed by the act of Mexico.

Military operations 1846

Military operations 1846

U.S. Politics

Peace

See also

Bibliography

Surveys

- Bancroft, H.H. History of Califroniaonline edition

- Bauer K. Jack. The Mexican War, 1846-1848. Macmillan, 1974.

- Crawford, Mark; Heidler, Jeanne T.; Heidler, David Stephen, eds. Encyclopedia of the Mexican War (1999) (ISBN 157607059X)

- De Voto, Bernard, Year of Decision 1846 (1942), very well written popular history

- Frazier, Donald S. ed. The U.S. and Mexico at War, (1998), 584; an encyclopedia with 600 articles by 200 scholars

- Meed, Douglas. The Mexican War, 1846-1848 (2003). 96pp by British scholar excerpt and text search

- Smith, Justin H. The War with Mexico 2 vol (1919); Pulitzer Prize; 2:233-52; online vol 1; online vol 2 Pulitzer Prize winner.

Military

- Bauer, K. Jack. Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest. (1985).

- Eisenhower, John. So Far From God: The U.S. War with Mexico, (1989) excerpt and text search

- Hamilton, Holman, Zachary Taylor: Soldier of the Republic , (1941)

- Johnson, Timothy D. Winfield Scott: The Quest for Military Glory (1998)

- Foos, Paul. A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict during the Mexican War (2002) excerpt and text search

- Lewis, Lloyd. Captain Sam Grant (1950)

- Winders, Richard Price. Mr. Polk's Army (1997) excerpt and text search

Political and Diplomatic

- Albert J. Beveridge; Abraham Lincoln, 1809-1858. Volume: 1. 1928.

- Gleijeses, Piero. "A Brush with Mexico" Diplomatic History 2005 29(2): 223-254. Issn: 0145-2096 debates in Washington before war

- Graebner, Norman A. Empire on the Pacific: A Study in American Continental Expansion. (1955).

- Graebner, Norman A. "Lessons of the Mexican War." Pacific Historical Review 47 (1978): 325-42.

- Graebner, Norman A. "The Mexican War: A Study in Causation." Pacific Historical Review 49 (1980): 405-26.

- Pletcher David M. The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War (1973).

- Price, Glenn W. Origins of the War with Mexico: The Polk-Stockton Intrigue. (1967).

- Schroeder John H. Mr. Polk's War: American Opposition and Dissent, 1846-1848. 1973.

- Sellers Charles G. James K. Polk: Continentalist, 1843-1846 (1966).

- Smith, Justin H. The War with Mexico 2 vol (1919); Pulitzer Prize; 2:233-52; online vol 1; online vol 2 Pulitzer Prize winner.

- Weinberg Albert K. Manifest Destiny: A Study of Nationalist Expansionism in American History (1935). ACLS e-book

Mexican perspectives

- Brack, Gene M. Mexico Views Manifest Destiny, 1821-1846: An Essay on the Origins of the Mexican War (1975).

- Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico (2007) 527pp; the major scholarly study

- Fowler, Will. Tornel and Santa Anna: The Writer and the Caudillo, Mexico, 1795-1853 (2000)

- Krauze, Enrique. Mexico: Biography of Power, (1997)

- Mayers, David; Fernández Bravo, Sergio A., "La Guerra Con Mexico Y Los Disidentes Estadunidenses, 1846-1848" [The War with Mexico and US Dissenters, 1846-48]. Secuencia [Mexico] 2004 (59): 32-70. Issn: 0186-0348

- Robinson, Cecil, The View From Chapultepec: Mexican Writers on the Mexican War, (1989)

- Rodríguez Díaz, María Del Rosario. "Mexico's Vision of Manifest Destiny During the 1847 War" Journal of Popular Culture 2001 35(2): 41-50. Issn: 0022-3840

- Ruiz, Ramon Eduardo. Triumph and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People, (1992)

- Yanez, Agustin. Santa Anna: Espectro de una sociedad (1996)

Primary Sources

- Polk, James. Polk: The Diary of a President, 1845-1849, Covering the Mexican War, the Acquisition of Oregon, and the Conquest of California and the Southwest. edited by Allan Nevins (1929)

- Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant

External links

- Handbook of Texas (2004), with many detailed scholarly articles

- Texas War for Independence 1832-36

- PBS on Mexican-American War

- West Point Atlas

- US Army textbook

- "The San Jacinto Campaign" 1901 article by leading scholar Eugene C. Barker

- Alamo images

- images of war

- Samuel Chamberlain memoirs and drawings

- Scott at Vera Cruz 1851 essay

- Edward D. Mansfield. The Mexican war: a history of its origin, and a detailed account of the victories which terminated in the surrender of the capital; with the official despatches of the generals. To which is added, the treaty of peace, and valuable tables of the strength and losses of the United States Army.(1860 ed.)

- "Pack Mules and Surf Boats: Logistics in the Mexican War" by Robert D. Paulus from Army Logistician 1997