Harmonic oscillator (quantum): Difference between revisions

imported>Paul Wormer No edit summary |

imported>Paul Wormer No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

The prototype of a '''harmonic oscillator''' is a mass ''m'' vibrating back and forth around an equilibrium position. In [[quantum mechanics]], the one-dimensional harmonic oscillator is one of the few systems that can be treated exactly. | |||

A large number of systems are governed (at least approximately) by the harmonic oscillator equation. Whenever one studies the behavior of a physical system in the neighborhood of a stable equilibrium position, one arrives at equations which, in the limit of small oscillations, are those of a harmonic oscillator. Two well-known examples are the vibrations of the atoms in a diatomic molecule about their equilibrium position and the oscillations of atoms or ions of a crystalline lattice. Also the energy of [[electromagnetic wave]]s in a cavity can be looked upon as the energy of a large set of harmonic oscillators. | |||

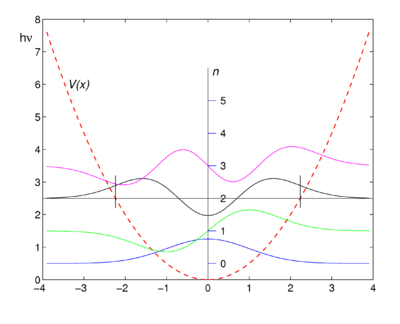

The four lowest harmonic oscillator eigenfunctions (also known as oscillator wave functions) are shown in the figure. They are shifted upward such that their energy eigenvalues coincide with the asympotic levels, | The four lowest harmonic oscillator eigenfunctions (also known as quantum mechanical oscillator wave functions) are shown in the figure below. They are shifted upward such that their energy eigenvalues coincide with the asympotic levels, the zero levels of the wave functions at ''x'' = ±∞. As an example of a zero level, the energy of the ''n'' = 2 function (black) is plotted, ''E''<sub>2</sub> = 5hν/2. | ||

According to quantum mechanics, the wave function squared of a point mass, |ψ(''x'')|², is the probability of finding the mass in the point ''x''. In the figure we see that the probability of finding the oscillating mass at points to the left or to the right of ''V''(''x'') is non-zero and we notice that for these points the potential energy ''V''(''x'') is larger than the energy eigenvalue. As an example two small vertical lines are plotted: to the left of the left line the potential energy is larger than <font style="vertical-align: baseline;"><math>E_2 = \ | According to quantum mechanics, the wave function squared of a point mass, |ψ(''x'')|², is the probability of finding the mass in the point ''x''. In the figure we see that the probability of finding the oscillating mass at points to the left or to the right of ''V''(''x'') is non-zero and we notice that for these points the potential energy ''V''(''x'') is larger than the energy eigenvalue. As an example two small vertical lines are plotted: to the left of the left line the potential energy is larger than <font style="vertical-align: baseline;"><math>E_2 = 5h\nu/2 \equiv \tfrac{5}{2} \hbar\omega</math></font>, the energy of the ''n'' = 2 level. The same holds for the region to the right of the small black line on the right. Note that the ''n'' = 2 wave function (black) is not zero in these regions. | ||

In classical mechanics the potential energy ''V'' can never surpass the total energy ''E'', because ''V'' = ''E'' − ''T'' and the classical kinetic energy ''T'' is non-negative, so that ''V'' ≤ ''E''. This is why the region, where the energy eigenvalue of an eigenfunction is smaller than the potential energy, is called a ''classically forbidden region''. The fact that the probability of finding a mass in a classically forbidden is not zero, is often expressed by stating that the point mass can ''tunnel'' into the potential wall. This tunnel effect is one of the more intriguing aspects of quantum mechanics. | In classical mechanics the potential energy ''V'' can never surpass the total energy ''E'', because ''V'' = ''E'' − ''T'' and the classical kinetic energy ''T'' is non-negative, so that ''V'' ≤ ''E''. This is why the region, where the energy eigenvalue of an eigenfunction is smaller than the potential energy, is called a ''classically forbidden region''. The fact that the probability of finding a mass in a classically forbidden is not zero, is often expressed by stating that the point mass can ''tunnel'' into the potential wall. This tunnel effect is one of the more intriguing aspects of quantum mechanics. | ||

Revision as of 08:47, 2 February 2009

The prototype of a harmonic oscillator is a mass m vibrating back and forth around an equilibrium position. In quantum mechanics, the one-dimensional harmonic oscillator is one of the few systems that can be treated exactly.

A large number of systems are governed (at least approximately) by the harmonic oscillator equation. Whenever one studies the behavior of a physical system in the neighborhood of a stable equilibrium position, one arrives at equations which, in the limit of small oscillations, are those of a harmonic oscillator. Two well-known examples are the vibrations of the atoms in a diatomic molecule about their equilibrium position and the oscillations of atoms or ions of a crystalline lattice. Also the energy of electromagnetic waves in a cavity can be looked upon as the energy of a large set of harmonic oscillators.

The four lowest harmonic oscillator eigenfunctions (also known as quantum mechanical oscillator wave functions) are shown in the figure below. They are shifted upward such that their energy eigenvalues coincide with the asympotic levels, the zero levels of the wave functions at x = ±∞. As an example of a zero level, the energy of the n = 2 function (black) is plotted, E2 = 5hν/2.

According to quantum mechanics, the wave function squared of a point mass, |ψ(x)|², is the probability of finding the mass in the point x. In the figure we see that the probability of finding the oscillating mass at points to the left or to the right of V(x) is non-zero and we notice that for these points the potential energy V(x) is larger than the energy eigenvalue. As an example two small vertical lines are plotted: to the left of the left line the potential energy is larger than , the energy of the n = 2 level. The same holds for the region to the right of the small black line on the right. Note that the n = 2 wave function (black) is not zero in these regions.

In classical mechanics the potential energy V can never surpass the total energy E, because V = E − T and the classical kinetic energy T is non-negative, so that V ≤ E. This is why the region, where the energy eigenvalue of an eigenfunction is smaller than the potential energy, is called a classically forbidden region. The fact that the probability of finding a mass in a classically forbidden is not zero, is often expressed by stating that the point mass can tunnel into the potential wall. This tunnel effect is one of the more intriguing aspects of quantum mechanics.

Schrödinger equation

The time-independent Schrödinger equation of the harmonic oscillator has the form

The two terms between square brackets are the Hamiltonian (energy operator) of the system: the first term is the kinetic energy operator and the second the potential energy operator. The quantity is Planck's reduced constant, m is the mass of the oscillator, and k is Hooke's spring constant. See the classical harmonic oscillator for further explanation of m and k.

The solutions of the Schrödinger equation are characterized by a vibration quantum number n = 0,1,2, .. and are of the form

with

Here

The functions Hn(x) are Hermite polynomials; the first few are:

The graphs of the first four eigenfunctions are shown in the figure. Note that the functions of even n are even, that is, , while those of odd n are antisymmetric

Solution of the Schrödinger equation

We rewrite the Schrödinger equation in order to hide the physical constants m, k, and h. As a first step we define the angular frequency ω ≡ √k/m, the same formula as for the classical harmonic oscillator:

Secondly, we divide through by , a factor that has dimension energy,

Write

and the Schrödinger equation becomes

Note that all constants are hidden in the equation on the right.

A particular solution of this equation is

We verify this

so that

We conclude that ψ0(y) ≡ exp(-y2/2) is an eigenfunction

with eigenvalue

This encourages us to try to find a total solution ψ(y) by a function of the form

Use the Leibniz formula

and

then we see

Divide through by −ψ0(y)/2 and we find the equation for f

The differential equation of Hermite with polynomial solutions Hn(y) is

Due to the appearance of the integer coefficient 2n in the last term the solutions are polynomials. We see that if we put

that we have solved the Schrödinger equation for the harmonic oscillator. The unnormalized solutions are

![{\displaystyle \left[-{\frac {\hbar ^{2}}{2m}}{\frac {\mathrm {d} ^{2}}{\mathrm {d} x^{2}}}+{\frac {1}{2}}kx^{2}\right]\psi =E\psi }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3d9f0668b35308e56ecebd650d35557a417587e9)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2}}\left[-{\frac {\hbar ^{2}}{m}}{\frac {\mathrm {d} ^{2}}{\mathrm {d} x^{2}}}+m\omega ^{2}x^{2}\right]\psi =E\psi .}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fa364b4f4b0b31d74933d03ba31283324a200e95)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2}}\left[-{\frac {\hbar }{m\omega }}{\frac {\mathrm {d} ^{2}}{\mathrm {d} x^{2}}}+{\frac {m\omega }{\hbar }}x^{2}\right]\psi ={\frac {E}{\hbar \omega }}\psi .}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2c52ece1d81ae4551f61d09b90fc3a758743f8ec)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2}}\left[-{\frac {1}{\beta ^{2}}}{\frac {\mathrm {d} ^{2}}{\mathrm {d} x^{2}}}+\beta ^{2}x^{2}\right]\psi ={\mathcal {E}}\psi \quad \Longrightarrow \quad {\frac {1}{2}}\left[-{\frac {\mathrm {d} ^{2}}{\mathrm {d} y^{2}}}+y^{2}\right]\psi ={\mathcal {E}}\psi .}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2d1d15092a4e7bb074de00b75c4b9275b33c4e54)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2}}\left[-{\frac {\mathrm {d} ^{2}}{\mathrm {d} y^{2}}}+y^{2}\right]e^{-y^{2}/2}={\frac {1}{2}}\left[e^{-y^{2}/2}\left(1-y^{2}\right)+y^{2}e^{-y^{2}/2}\right]={\frac {1}{2}}e^{-y^{2}/2}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/93a7d91461e3cd6e73134967273d97d75c50c217)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2}}\left[-{\frac {\mathrm {d} ^{2}}{\mathrm {d} y^{2}}}+y^{2}\right]\psi _{0}={\frac {1}{2}}\psi _{0},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f1aeb8aa73a43901e4177ddbfdcfb0c947936dff)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2}}\left[-{\frac {d^{2}\psi _{0}}{dy^{2}}}+y^{2}\psi _{0}\right]f={\frac {1}{2}}\psi _{0}f\quad {\hbox{and}}\quad {\frac {d\psi _{0}}{dy}}=-y\psi _{0}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cf2e580c99c1105a568c3c229230f09a3d3960c9)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2}}\left[-{\frac {d^{2}(\psi _{0}f)}{dy^{2}}}+y^{2}\psi _{0}f\right]={\frac {1}{2}}\psi _{0}f+y\psi _{0}{\frac {df}{dy}}-{\frac {1}{2}}{\frac {d^{2}f}{dy^{2}}}\psi _{0}={\mathcal {E}}\psi _{0}f.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5b28e76d23647ec69af861bee1b0a4c6d132f231)