Volatility (chemistry): Difference between revisions

imported>Milton Beychok m (Undo revision 100720980 by Milton Beychok (Talk) Undid 2nd wiki link of temperature) |

imported>Milton Beychok m (Good edits, Anthony. My only change is that I prefer the word "tendency" rather than "readiness". See Talk page.) |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

{{Main|Vapor pressure|boiling point|Antoine equation}} | {{Main|Vapor pressure|boiling point|Antoine equation}} | ||

The vapor pressure of a substance is the pressure at which its gaseous (vapor) phase is in equilibrium with its liquid or solid phase. It is a measure of the | The vapor pressure of a substance is the pressure at which its gaseous (vapor) phase is in equilibrium with its liquid or solid phase. It is a measure of the tendency of [[molecule]]s and [[atom]]s to escape from a liquid or solid. | ||

At [[atmospheric pressure]]s, when a liquid's vapor pressure increases with increasing temperatures to the point at which it equals the atmospheric pressure, the liquid has reached its [[boiling point]], namely, the temperature at which the liquid changes its state from a liquid to a gas throughout its bulk. That temperature is very commonly referred to as the liquid's ''normal boiling point''. | At [[atmospheric pressure]]s, when a liquid's vapor pressure increases with increasing temperatures to the point at which it equals the atmospheric pressure, the liquid has reached its [[boiling point]], namely, the temperature at which the liquid changes its state from a liquid to a gas throughout its bulk. That temperature is very commonly referred to as the liquid's ''normal boiling point''. | ||

Not surprisingly, a liquid's normal boiling point will be at a lower temperature the greater | Not surprisingly, a liquid's normal boiling point will be at a lower temperature the greater of its molecules to escape from the liquid, namely, the higher its vapor pressure. In other words, the higher is the vapor pressure of a liquid, the higher is the volatility and the lower is the normal boiling point of the liquid. The adjacent vapor pressure chart graphs the dependency of vapor pressure upon temperature for a variety of liquids<ref name=Perry>{{cite book|author=R.H. Perry and D.W. Green (Editors)|title=Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook | edition=7th Edition|publisher=McGraw-Hill|year=1997|id=ISBN 0-07-049842-5}}</ref> and also confirms that liquids with higher vapor pressures have lower normal boiling points. | ||

For example, at any given temperature, methyl chloride (CH<sub>3</sub>Cl) has the highest vapor pressure of any of the liquids graphed in the chart. It also has the lowest normal boiling point (−26 °C), which is where its vapor pressure curve (the blue line) intersects the horizontal pressure line of one [[atmosphere (unit)|atmosphere]] (atm) of absolute vapor pressure. | For example, at any given temperature, methyl chloride (CH<sub>3</sub>Cl) has the highest vapor pressure of any of the liquids graphed in the chart. It also has the lowest normal boiling point (−26 °C), which is where its vapor pressure curve (the blue line) intersects the horizontal pressure line of one [[atmosphere (unit)|atmosphere]] (atm) of absolute vapor pressure. | ||

Revision as of 15:18, 14 October 2010

In chemistry and physics, volatility is a term used to characterize the tendency of a substance to vaporize.[1] It is directly related to a substance' s vapor pressure. At a given temperature, a substance with a higher vapor pressure will vaporize more readily than a substance with a lower vapor pressure.[2][3][4] In other words, at a given temperature, the more volatile the substance the higher will be the pressure of the vapor in dynamic equilibrium with its vaporizing substance—i.e., when the rates at which molecules escape from and return into the vaporizing substance are equal.

In common usage, the term applies primarily to liquids. However, it may also be used to characterize the process of sublimation by which certain solid substances such as ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) and dry ice, which is solid carbon dioxide (CO2), change directly from their solid form to a vapor without becoming a liquid.

Any substance with a significant vapor pressure at temperatures of about 20 to 25 °C (68 to 77 °F) is very often referred to as being volatile.

Vapor pressure, temperature and boiling point

The vapor pressure of a substance is the pressure at which its gaseous (vapor) phase is in equilibrium with its liquid or solid phase. It is a measure of the tendency of molecules and atoms to escape from a liquid or solid.

At atmospheric pressures, when a liquid's vapor pressure increases with increasing temperatures to the point at which it equals the atmospheric pressure, the liquid has reached its boiling point, namely, the temperature at which the liquid changes its state from a liquid to a gas throughout its bulk. That temperature is very commonly referred to as the liquid's normal boiling point.

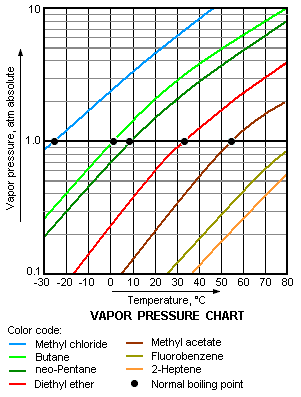

Not surprisingly, a liquid's normal boiling point will be at a lower temperature the greater of its molecules to escape from the liquid, namely, the higher its vapor pressure. In other words, the higher is the vapor pressure of a liquid, the higher is the volatility and the lower is the normal boiling point of the liquid. The adjacent vapor pressure chart graphs the dependency of vapor pressure upon temperature for a variety of liquids[5] and also confirms that liquids with higher vapor pressures have lower normal boiling points.

For example, at any given temperature, methyl chloride (CH3Cl) has the highest vapor pressure of any of the liquids graphed in the chart. It also has the lowest normal boiling point (−26 °C), which is where its vapor pressure curve (the blue line) intersects the horizontal pressure line of one atmosphere (atm) of absolute vapor pressure.

In terms of intermolecular forces, the boiling point represents the temperature at which the liquid molecules possess enough kinetic energy to overcome the various intermolecular attractions binding the molecules to each other within the liquid. Therefore the boiling point is also an indicator of the strength of those attractive forces. The higher the intermolecular attractive forces are, the more difficult it is for molecules to escape from the liquid and hence the lower is the vapor pressure of the liquid. The lower the vapor pressure of the liquid, the higher the temperature must be to initiate boiling. Thus, the higher the intermolecular attractive forces are, the higher is the normal boiling point.[6]

Relative volatility

Relative volatility refers to a measure of the difference between the vapor pressure of the more volatile components of a liquid mixture and the vapor pressure of the less volatile components of the mixture. This measure is widely used in designing large industrial distillation processes.[4][5][7] In effect, it indicates the ease or difficulty of using distillation to separate the more volatile components from the less volatile components in a mixture. The use of relative volatility applies to multi-component liquid mixtures as well as to binary mixtures. By convention, relative volatility is typically denoted as α.

Volatile Organic Compound

The term Volatile organic compound (VOC) refers to organic chemical compounds having significant vapor pressures and which can have adverse effects on the environment and human health. VOCs are numerous, varied and include man-made (anthropogenic) as well as naturally occurring chemical compounds. The anthropogenic VOCs are regulated by various governmental environmental entities worldwide.

There is no universally accepted definition of VOCs. Some regulatory entities define them in terms of their vapor pressure at ordinary temperatures, or their normal boiling points, or how many carbon atoms they contain per molecule, and others define them in terms of their photochemical reactivity.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency currently defines them as any compound of carbon, excluding carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, carbonic acid, metallic carbides or carbonates, and ammonium carbonate, which participates in atmospheric photochemical reactions (i.e., the reactions that produce photochemical smog. However, any such carbon compounds that have been determined to have a low photochemical reactivity, and specifically listed in the regulation, are exempted from regulation.[8]

Special definitions

There are a number of special definitions of the terms volatility and volatile commonly used in certain fields of study but which are still within the overall context of chemistry:

Wine making

The wine industry uses the term volatile acids to refer to organic acids that are water-soluble, have short carbon chains (six carbon atoms or less) and which occur in wine. For example: carbonic acid, acetic acid, formic acid, butyric acid and proprionic acid.

Cosmetics and flavorings

Certain volatile oils obtained from plants have distinctive, pleasant aromas which are used in cosmetics and food flavorings. These oils are commonly referred to as essential oils

Coal

Coals contain a certain amount of volatile matter, defined as the portion of a coal sample which, when heated in the absence of air, is released as inorganic and organic gases.

Anesthetics

Inhalational anesthetics, commonly referred to as volatile anesthetics are organic liquids at room temperature which are easily vaporized. Some examples are:halothane, isoflurane and sevoflurane.

Special areas of volatility research and technology development

Odors from volatile substances acting as social behavioral signals or codes

The ability to recognize individuals or their genetic relatedness has an important role in the social behavior of mammals. Mammalian social systems rely on signals passed between individuals that provide information about sex, reproductive status, individual identity, ownership, competitive ability and health status. Many of these signals take the form of volatile substances that are used to signal at a distance and are sensed by the mammalian olfactory systems. Despite the complexities of all mammalian societies, there are instances where volatile single molecules can act as classical pheromones attracting interest and approach behavior. The behavior of most, if not all, insect species are also highly dependent upon the olfactory perception of odors from volatile substances.

Comprehensive reviews of the research work in this area are available on the Internet.[9][10]

Ionic liquids

Ionic liquids consist exclusively, or almost exclusively, of ions and were traditionally known in the past as "molten salts". Over the past twenty years or so, they have become to be defined as salts having melting points below the arbitrarily chosen temperature of 100 °C. Most ionic liquids consist of organic cations and either organic or inorganic anions. Binary mixtures of an organic salt and an inorganic salt are also ionic liquids. Aqueous solutions of salts are not classified as ionic liquids because they do not consist exclusively of ions.[11]

The origins of ionic liquid chemistry began with the work of chemists Charles Friedel and James F. Crafts in 1877 and Siegmund Gabriel in 1888. The term "ionic liquids" was first coined in 1961 by another chemist, H. Bloom, at a Faraday Society discussion.[11][12][13][14] Over the years since then, various names and acronyms have been used in the scientific literature for organic salts with low melting points, including ionic liquid (IL), room temperature ionic liquid (RTIL), ambient temperature ionic liquid, non-aqueous ionic liquid (NAIL) and molten organic salt.

Ionic liquids have attracted the attention of chemists for many reasons:[11]

- The potential for research on ionic liquids is very great. More than 1500 ionic liquids have already been reported in the scientific literature and, in theory, a million or so simple ionic liquids are possible. An almost limitless number of ionic liquids are theoretically possible by mixing two or more simple ionic liquids.

- Unlike organic molecular solvents, ionic liquids have negligible vapor pressures and therefore do not undergo evaporation under normal ambient conditions. For that reason, they are looked upon as "environmentally friendly" and "green" replacements for VOCs.[15]

- Ionic liquids are generally non-flammable and many remain thermally stable at temperatures higher than conventional organic molecular solvents.

- Ionic liquids can be used as chemical reaction media and/or catalysts for a wide variety of chemical reactions.

- The physical, chemical and biochemical properties of ionic liquids can be "tailored" or "designed" by switching anions or cations, by mixing two or more simple ionic liquids and by designing special functionalities into the anions and/or cations.

- Ionic liquids have many applications in electrochemistry, biochemistry and other branches of chemistry.

A comprehensive review of the environmental fate and toxicity of ionic liquids concluded that their low volatility does not eliminate potential environmental hazards and may have serious adverse consequences for aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. That review recommends more research and more studies be conducted into the environmental aspects of ionic liquids.[15]

References

- ↑ Note: To vaporize means to become a vapor, the gaseous state of the substance.

- ↑ Gases and Vapor (University of Kentucky website)

- ↑ James G. Speight (2006). The Chemistry and Technology of Petroleum, 4th Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-9067-2.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kister, Henry Z. (1992). Distillation Design, 1st Edition. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-034909-6.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 R.H. Perry and D.W. Green (Editors) (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook, 7th Edition. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049842-5.

- ↑ The Nature of Intermolecular Forces From the Louisiana State University Chemistry Department website.

- ↑ Seader, J. D., and Henley, Ernest J. (1998). Separation Process Principles. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-58626-9.

- ↑ U.S. Code of Federal Regulations: 40 CFR 51.100(s) - Definition - Volatile organic compounds (VOC)

- ↑ Peter Brennan and Keith Kendrick (2006). "Mammalian social odours: attraction and individual recognition". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 261 (1476): 2061-2078.

- ↑ M. de Bruyne and T. C. Baker (2008). "Odor Detection in Insects: Volatile Codes". J. Chem. Eco. 34: 882-897.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Michael Freemantle (2009). An Introduction to Ionic Liquids, 1st Edition. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 1-84755-161-0.

- ↑ Charles Friedel and James M. Crafts (1877). "Sur une nouvelle méthode générale de synthèse d'hydrocarbures, d'acétones, etc.". Compt. Rend. 84: pages 1392 and 1450.

- ↑ Siegmund Gabriel and J. Weiner (1887). "Ueber einige Abkömmlinge des Propylamins". Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft 21 (2): pages 2669 - 2674.

- ↑ H. Bloom (1961). "Eleventh Spiers Memorial Lecture: Structural models for molten salts and their mixtures" 32: pages 7-13.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Thi Phuong Thuy Pham, Chul-Woong Cho and Yeoung-Sang Yun (2010). "Environmental fate and toxicity of ionic liquids: A review". Water Research 34 (2): pages 352-372.

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- CZ Live

- Chemistry Workgroup

- Biology Workgroup

- Engineering Workgroup

- Chemical Engineering Subgroup

- Environmental Engineering Subgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- Chemistry Content

- Biology Content

- Engineering Content

- Chemical Engineering tag

- Environmental Engineering tag