Spanish missions in Baja California: Difference between revisions

imported>Pat Palmer (→The Mission Trail: enlarging the image of the map) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "United States" to "United States of America") |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

{{Main|Mexico, history}} | {{Main|Mexico, history}} | ||

===Early exploration and contact=== | ===Early exploration and contact=== | ||

Beginning in 1492 with the voyages of [[Christopher Columbus]], the Kingdom of Spain sought to establish missions to convert the pagans in ''Nueva España'' ("New Spain," consisting of the [[Caribbean]], [[Mexico]] and most of what today is the Southwestern [[United States]]) to Roman Catholicism, in order to facilitate colonization of these lands awarded to Spain by the Catholic Church.<ref>The Spanish claim to the Pacific Northwest had dated back to a 1493 papal bull (''Inter caetera'') and rights contained in the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas; these two formal acts gave Spain the exclusive rights to colonize all of the Western Hemisphere (excluding Brazil), including the exclusive rights to colonize all of the the west coast of North America.</ref> The mission system arose in part from the need to control Spain's ever-expanding holdings in the New World. Realizing that the colonies would require a literate population base that the mother country could not supply, the government (with the cooperation of the Church) established a network of missions with the goal of converting the natives to Christianity; the aim was to make converts and tax paying citizens of the indigenous peoples they conquered.<ref>Bennett 1897a, p. 10: "''Other pioneers have blazed the way for civilization by the torch and the bullet, and the red man has disappeared before them; but it remained for the Spanish priests to undertake to preserve the Indian and seek to make his existence compatible with a higher civilization''."</ref> In order to become Spanish citizens and productive inhabitants, the native Americans were required to learn Spanish language and vocational skills along with Christian teachings. | Beginning in 1492 with the voyages of [[Christopher Columbus]], the Kingdom of Spain sought to establish missions to convert the pagans in ''Nueva España'' ("New Spain," consisting of the [[Caribbean]], [[Mexico]] and most of what today is the Southwestern [[United States of America]]) to Roman Catholicism, in order to facilitate colonization of these lands awarded to Spain by the Catholic Church.<ref>The Spanish claim to the Pacific Northwest had dated back to a 1493 papal bull (''Inter caetera'') and rights contained in the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas; these two formal acts gave Spain the exclusive rights to colonize all of the Western Hemisphere (excluding Brazil), including the exclusive rights to colonize all of the the west coast of North America.</ref> The mission system arose in part from the need to control Spain's ever-expanding holdings in the New World. Realizing that the colonies would require a literate population base that the mother country could not supply, the government (with the cooperation of the Church) established a network of missions with the goal of converting the natives to Christianity; the aim was to make converts and tax paying citizens of the indigenous peoples they conquered.<ref>Bennett 1897a, p. 10: "''Other pioneers have blazed the way for civilization by the torch and the bullet, and the red man has disappeared before them; but it remained for the Spanish priests to undertake to preserve the Indian and seek to make his existence compatible with a higher civilization''."</ref> In order to become Spanish citizens and productive inhabitants, the native Americans were required to learn Spanish language and vocational skills along with Christian teachings. | ||

On January 29, 1767 King Charles III ordered the Jesuits, who had established a chain of fifteen missions throughout [[Baja California]], forcibly expelled and returned to the home country.<ref>Bennett 1897a, p. 15: Due to the isolation of the Baja California missions, the decree for expulsion did not arrive in June of 1767, as it did in the rest of New Spain, but was delayed until the new governor, Portolà, arrived with the news on November 30. Jesuits from the operating missions gathered in Loreto, whereupon they left for exile on February 3, 1768.</ref> ''Visitador General'' José de Gálvez engaged the Franciscans, under the leadership of Fray Junípero Serra, to take charge of those outposts on March 12, 1768.<ref>Bennett 1897a, p. 16</ref> The ''padres'' closed or consolidated several of the existing settlements, and also founded ''[[La Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá]]'' (the only Franciscan mission in all of Baja California) and the nearby ''[[Visita de la Presentación]]'' in 1769. This plan, however, was changed within a few months after Gálvez received the following orders: "''Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God and the King of Spain.''" <ref>James, p. 11</ref> It was thereupon decided to call upon the priests of the Dominican Order to take charge of the Baja California missions in order to allow the Franciscans to concentrate on founding new missions in Alta California.<ref>Guest: "''The blueprint for Alta California provided for a system of settlements significantly different from those in Baja California and Sonora. In their original design, both presidios and missions were different from their predecessors to the south. The plan to make the presidios agriculturally productive did not succeed. Neither did the plan for the mission-pueblos as racially integrated nuclei of urban centers, but the ideal of a closer association between "missionized" Indians and ''gente de razón'', notwithstanding the opposition of the friars, was partially realized.</ref> | On January 29, 1767 King Charles III ordered the Jesuits, who had established a chain of fifteen missions throughout [[Baja California]], forcibly expelled and returned to the home country.<ref>Bennett 1897a, p. 15: Due to the isolation of the Baja California missions, the decree for expulsion did not arrive in June of 1767, as it did in the rest of New Spain, but was delayed until the new governor, Portolà, arrived with the news on November 30. Jesuits from the operating missions gathered in Loreto, whereupon they left for exile on February 3, 1768.</ref> ''Visitador General'' José de Gálvez engaged the Franciscans, under the leadership of Fray Junípero Serra, to take charge of those outposts on March 12, 1768.<ref>Bennett 1897a, p. 16</ref> The ''padres'' closed or consolidated several of the existing settlements, and also founded ''[[La Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá]]'' (the only Franciscan mission in all of Baja California) and the nearby ''[[Visita de la Presentación]]'' in 1769. This plan, however, was changed within a few months after Gálvez received the following orders: "''Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God and the King of Spain.''" <ref>James, p. 11</ref> It was thereupon decided to call upon the priests of the Dominican Order to take charge of the Baja California missions in order to allow the Franciscans to concentrate on founding new missions in Alta California.<ref>Guest: "''The blueprint for Alta California provided for a system of settlements significantly different from those in Baja California and Sonora. In their original design, both presidios and missions were different from their predecessors to the south. The plan to make the presidios agriculturally productive did not succeed. Neither did the plan for the mission-pueblos as racially integrated nuclei of urban centers, but the ideal of a closer association between "missionized" Indians and ''gente de razón'', notwithstanding the opposition of the friars, was partially realized.</ref> | ||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

====Site selection and layout==== | ====Site selection and layout==== | ||

In addition to the ''presidio'' (royal fort) and ''pueblo'' (town), the ''misión'' was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its [[colonial]] territories. ''Asistencias'' {"sub-missions" or "contributing chapels") were small-scale missions that regularly conducted Divine service on days of obligation but lacked a resident priest; ''visitas'' ("visiting chapels") also lacked a resident priest, and were often attended only sporadically. Since 1493, the Kingdom of [[Spain]] had maintained a number of missions throughout ''Nueva España'' ([[New Spain]], consisting of [[Mexico]] and portions of what today are the [[Southwestern United States|Southwestern]] [[United States]]) in order to facilitate colonization of these lands. Each [[frontier]] station was forced to be self-supporting, as existing means of supply were inadequate to maintain a colony of any size. In order to sustain a mission, the ''padres'' required the help of [[colonist]]s or converted [[Native Americans in the United States|Native Americans]], called ''neophytes'', to cultivate [[agriculture|crops]] and tend [[livestock]] in the volume needed to support a fair-sized establishment. The scarcity of imported materials, together with a lack of skilled laborers, compelled the Fathers to employ simple building materials and methods in the construction of mission structures. Although the missions were considered temporary ventures by the Spanish [[hierarchy]], the development of an individual settlement was not simply a matter of "priestly whim." The founding of a mission followed longstanding rules and procedures; the paperwork involved required months, sometimes years of correspondence, and demanded the attention of virtually every level of the bureaucracy. Once empowered to erect a mission in a given area, the men assigned to it chose a specific site that featured a good water supply, plenty of wood for fires and building material, and ample fields for grazing [[herds]] and raising [[agriculture|crops]]. The padres blessed the site, and with the aid of their [[military]] escort fashioned temporary shelters out of tree limbs or driven stakes, roofed with [[thatch]] or [[reed (plant)|reed]]s (''cañas''). It was these simple huts that would ultimately give way to the stone and adobe buildings which exist to this day. | In addition to the ''presidio'' (royal fort) and ''pueblo'' (town), the ''misión'' was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its [[colonial]] territories. ''Asistencias'' {"sub-missions" or "contributing chapels") were small-scale missions that regularly conducted Divine service on days of obligation but lacked a resident priest; ''visitas'' ("visiting chapels") also lacked a resident priest, and were often attended only sporadically. Since 1493, the Kingdom of [[Spain]] had maintained a number of missions throughout ''Nueva España'' ([[New Spain]], consisting of [[Mexico]] and portions of what today are the [[Southwestern United States|Southwestern]] [[United States of America]]) in order to facilitate colonization of these lands. Each [[frontier]] station was forced to be self-supporting, as existing means of supply were inadequate to maintain a colony of any size. In order to sustain a mission, the ''padres'' required the help of [[colonist]]s or converted [[Native Americans in the United States|Native Americans]], called ''neophytes'', to cultivate [[agriculture|crops]] and tend [[livestock]] in the volume needed to support a fair-sized establishment. The scarcity of imported materials, together with a lack of skilled laborers, compelled the Fathers to employ simple building materials and methods in the construction of mission structures. Although the missions were considered temporary ventures by the Spanish [[hierarchy]], the development of an individual settlement was not simply a matter of "priestly whim." The founding of a mission followed longstanding rules and procedures; the paperwork involved required months, sometimes years of correspondence, and demanded the attention of virtually every level of the bureaucracy. Once empowered to erect a mission in a given area, the men assigned to it chose a specific site that featured a good water supply, plenty of wood for fires and building material, and ample fields for grazing [[herds]] and raising [[agriculture|crops]]. The padres blessed the site, and with the aid of their [[military]] escort fashioned temporary shelters out of tree limbs or driven stakes, roofed with [[thatch]] or [[reed (plant)|reed]]s (''cañas''). It was these simple huts that would ultimately give way to the stone and adobe buildings which exist to this day. | ||

The first priority when beginning a settlement was the location and construction of the [[church]] (''iglesia''). The majority of mission sanctuaries were oriented on a roughly east-west axis to take the best advantage of the sun's position for interior [[illumination (lighting)|illumination]]; the exact alignment depended on the geographic features of the particular site. Once the spot for the church was selected, its position would be marked and the remainder of the mission complex would be laid out. The [[workshop]]s, [[kitchen]]s, living quarters, storerooms, and other ancillary chambers were usually grouped in the form of a [[quadrangle]], inside which religious celebrations and other festive events often took place. The ''cuadrángulo'' was rarely a perfect square because the Fathers had no [[surveying]] instruments at their disposal and simply measured off all dimensions by foot. | The first priority when beginning a settlement was the location and construction of the [[church]] (''iglesia''). The majority of mission sanctuaries were oriented on a roughly east-west axis to take the best advantage of the sun's position for interior [[illumination (lighting)|illumination]]; the exact alignment depended on the geographic features of the particular site. Once the spot for the church was selected, its position would be marked and the remainder of the mission complex would be laid out. The [[workshop]]s, [[kitchen]]s, living quarters, storerooms, and other ancillary chambers were usually grouped in the form of a [[quadrangle]], inside which religious celebrations and other festive events often took place. The ''cuadrángulo'' was rarely a perfect square because the Fathers had no [[surveying]] instruments at their disposal and simply measured off all dimensions by foot. | ||

Revision as of 13:12, 2 February 2023

The Spanish missions in Baja California comprise a series of twenty-eight religious outposts (along with their associated support facilities) established by Spaniards of the Dominican, Franciscan, and Jesuit Orders between 1683 and 1834, in order to spread the Catholic faith among the local Native American populations. The missions represented the first major effort by Europeans to colonize the region, and gave Spain a valuable foothold in the frontier land via enforcement of historic Spanish claims. The settlers introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and industry into the region. European contact was a momentous event, which profoundly affected Baja California's native peoples. Ultimately, the mission system failed in its objective to convert, educate, and "civilize" the indigenous population in order to transform the Baja California natives into Spanish colonial citizens.

History

Precontact

Early exploration and contact

Beginning in 1492 with the voyages of Christopher Columbus, the Kingdom of Spain sought to establish missions to convert the pagans in Nueva España ("New Spain," consisting of the Caribbean, Mexico and most of what today is the Southwestern United States of America) to Roman Catholicism, in order to facilitate colonization of these lands awarded to Spain by the Catholic Church.[3] The mission system arose in part from the need to control Spain's ever-expanding holdings in the New World. Realizing that the colonies would require a literate population base that the mother country could not supply, the government (with the cooperation of the Church) established a network of missions with the goal of converting the natives to Christianity; the aim was to make converts and tax paying citizens of the indigenous peoples they conquered.[4] In order to become Spanish citizens and productive inhabitants, the native Americans were required to learn Spanish language and vocational skills along with Christian teachings.

On January 29, 1767 King Charles III ordered the Jesuits, who had established a chain of fifteen missions throughout Baja California, forcibly expelled and returned to the home country.[5] Visitador General José de Gálvez engaged the Franciscans, under the leadership of Fray Junípero Serra, to take charge of those outposts on March 12, 1768.[6] The padres closed or consolidated several of the existing settlements, and also founded La Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá (the only Franciscan mission in all of Baja California) and the nearby Visita de la Presentación in 1769. This plan, however, was changed within a few months after Gálvez received the following orders: "Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God and the King of Spain." [7] It was thereupon decided to call upon the priests of the Dominican Order to take charge of the Baja California missions in order to allow the Franciscans to concentrate on founding new missions in Alta California.[8]

Founding

Expeditions

Fortún Jiménez de Bertadoña discovered the Baja California Peninsula in early 1534. However, it was Hernán Cortés who recognized the peninsula as the "Island of California" in May 1535, and is therefore officially credited with the discovery. In January 1683, the Spanish government chartered an expedition consisting of three ships to transport a contingent of 200 men to the southern tip of Baja California. Under the command of the governor of Sinaloa, Isidoro de Atondo y Antillon, and accompanied by Jesuit priest Eusebio Francisco Kino, the ships made landfall in La Paz. The landing party was eventually forced to abandon its initial settlement at San Bruno due to the hostile response on the part of the natives. In 1695, the missionaries attempted to establish a settlement near Loreto but again failed. Father Kino and Atondo y Antillon returned to the Mexican mainland, where Kino went on to establish several missions in the northwest.

Site selection and layout

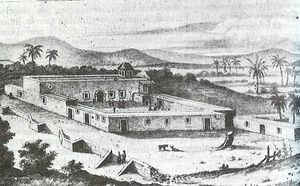

In addition to the presidio (royal fort) and pueblo (town), the misión was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its colonial territories. Asistencias {"sub-missions" or "contributing chapels") were small-scale missions that regularly conducted Divine service on days of obligation but lacked a resident priest; visitas ("visiting chapels") also lacked a resident priest, and were often attended only sporadically. Since 1493, the Kingdom of Spain had maintained a number of missions throughout Nueva España (New Spain, consisting of Mexico and portions of what today are the Southwestern United States of America) in order to facilitate colonization of these lands. Each frontier station was forced to be self-supporting, as existing means of supply were inadequate to maintain a colony of any size. In order to sustain a mission, the padres required the help of colonists or converted Native Americans, called neophytes, to cultivate crops and tend livestock in the volume needed to support a fair-sized establishment. The scarcity of imported materials, together with a lack of skilled laborers, compelled the Fathers to employ simple building materials and methods in the construction of mission structures. Although the missions were considered temporary ventures by the Spanish hierarchy, the development of an individual settlement was not simply a matter of "priestly whim." The founding of a mission followed longstanding rules and procedures; the paperwork involved required months, sometimes years of correspondence, and demanded the attention of virtually every level of the bureaucracy. Once empowered to erect a mission in a given area, the men assigned to it chose a specific site that featured a good water supply, plenty of wood for fires and building material, and ample fields for grazing herds and raising crops. The padres blessed the site, and with the aid of their military escort fashioned temporary shelters out of tree limbs or driven stakes, roofed with thatch or reeds (cañas). It was these simple huts that would ultimately give way to the stone and adobe buildings which exist to this day.

The first priority when beginning a settlement was the location and construction of the church (iglesia). The majority of mission sanctuaries were oriented on a roughly east-west axis to take the best advantage of the sun's position for interior illumination; the exact alignment depended on the geographic features of the particular site. Once the spot for the church was selected, its position would be marked and the remainder of the mission complex would be laid out. The workshops, kitchens, living quarters, storerooms, and other ancillary chambers were usually grouped in the form of a quadrangle, inside which religious celebrations and other festive events often took place. The cuadrángulo was rarely a perfect square because the Fathers had no surveying instruments at their disposal and simply measured off all dimensions by foot.

Mission Period (1683 – 1834)

A Jesuit priest named Juan María de Salvatierra eventually managed to establish the first permanent Spanish settlement, the Misión Nuestra Senora de Loreto Conchó. Founded, on October 19, 1697, the Mission went on to become the religious and administrative capital of Baja California. From there, other Jesuits went out to establish other settlements throughout the peninsula, founding a total of 18 missions and two visitas ("visiting stations" or "country chapels") along the initial segment of El Camino Real over the next seven decades. Unlike the mainland settlements that were designed to be self-sustaining enterprises, the remote and harsh conditions on the peninsula made it all but impossible to build and maintain these missions without ongoing assistance from the mainland. Supply lines from across the Sea of Cortez in the Port of Guaymas played a crucial role in keeping the Baja mission system intact. Along with religion, the Europeans brought with them diseases that the indigenous peoples had never been exposed to, and consequently had no immunity against. By 1767, epidemics of measles, plague, smallpox, typhus, and venereal diseases had decimated the native population. Out of an initial population of as many as 50,000, only some 5,000 are thought to have survived.

During the sixty years that the Jesuits were permitted to serve among the natives of California, 56 members of the Society of Jesus came to the Baja peninsula, of whom 16 died at their posts (two as martyrs). Fifteen priests and one lay brother survived the hardships, only to be subjected to enforcement of the brutal decree launched against the Society by King Carlos III of Spain. It was rumored that the Jesuit priests had amassed a fortune on the peninsula and were becoming very powerful. On February 3, 1768 the King ordered the Jesuits forcibly expelled from "New Spain" and returned to the home country. The Franciscans, under the leadership of Fray Junípero Serra, took charge of the missions and closed or consolidated several of the existing installations. The order also founded Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá (the only Franciscan mission in all of Baja California) and the nearby Visita de la Presentación in 1769. A total of 39 Friars Minor toiled on the peninsula during the five years and five months of Franciscan rule. 4 of them died, 10 were transferred to Alta California, and the remainder returned to Europe. Along with Governor Gaspar de Portolà, Father Serra was ordered by the Spanish government to travel north and establish a series of mission sites in Alta (Upper) California.[9]

Representatives of the Dominican Order arrived in 1772, and by 1800, had established 9 more missions in northern Baja, all the while continuing with the administration of the former the Jesuit missions. The peninsula was divided into two separate entities in 1804, with the southern one having the seat of government established in the Port of Loreto. In 1810, Mexico sought to end Spanish colonial rule, gaining her independence in 1821, after which Mexican President Guadalupe Victoria named Lt. Col. José María Echeandía governor of Baja California Sur and divided it in four separate municipios (municipalities). The capital was moved to La Paz, in 1830, after Loreto was partially destroyed by heavy rains. In 1833, after Baja was designated as a federal territory, the governor formally put an end to the mission system by converting the missions into parish churches.

The Mission Trail

A network of settlements was established over time wherein each of the installations was no more than a long day's ride by horse or boat (or three days on foot) from the the next one in the chain.

In geographical order, north to south

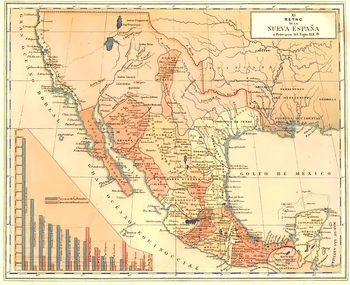

An early map traces the overland Baja California Peninsula route of Gaspar de Portolà and Father Junípero Serra in Nueva España in 1769, from Loreto, Baja California, to the site of San Diego in Las Californias.

Baja California (Norte)

- Misión El Descanso (Misión San Miguel la Nueva), located in Rosarito

- Misión de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe del Norte, located in Guadalupe

- Misión San Miguel Arcángel de la Frontera, located in Ensenada

- Misión Santa Catarina Virgen y Mártir, located in Ensenada

- Misión Santo Tomás de Aquino

- Misión San Vicente Ferrer

- Misión Santo Domingo de la Frontera, located near Colonia Vicente Guerrero

- Misión San Pedro Mártir de Verona

- Misión Nuestra Señora del Santísimo Rosario de Viñacado, located near El Rosario

- Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá

- Visita de Calamajué (Visita de Calamyget) in Calamajué

- Misión Santa María de los Ángeles, located near Cataviña

- Misión San Francisco Borja

- Misión Santa Gertrudis

Baja California Sur

- Misión San Ignacio Kadakaamán, located in San Ignacio

- Misión Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Huasinapi, located in Guadalupe

- Visita de San José de Magdalena, located in Santa Rosalía

- Misión Santa Rosalía de Mulegé, located in Mulegé

- Misión San Bruno,located in San Bruno

- Misión La Purísima Concepción de Cadegomó, located in La Purísima

- Misión San Jose de Comondú, located north of Loreto

- Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó, located in Loreto

- Misión San Francisco Javier de Viggé-Biaundó, located in San Javier

- Misión San Juan Bautista Malibat (Misión Liguí), located in Liguí

- Misión Nuestra Señora de los Dolores del Sur Chillá, located between Loreto and La Paz

- Misión San Luis Gonzaga Chiriyaqui, located northwest of La Paz

- Misión de Nuestra Señora del Pilar de La Paz Airapí, located in La Paz

- Misión Santa Rosa de las Palmas, located in Todos Santos

- Misión Santiago de Los Coras, located in Santiago

- Misión Estero de las Palmas de San José del Cabo Añuití, located in San José del Cabo

Notes

USNS Mission Loreto (T-AO-116) underway in the Long Beach Harbor area, date unknown. Mission Loreto was the only United States naval vessel to be named for one of the Baja California missions.

- ↑ (PD) Drawing: Antonio García Cubas

- ↑ Saunders and Chase, p. 65

- ↑ The Spanish claim to the Pacific Northwest had dated back to a 1493 papal bull (Inter caetera) and rights contained in the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas; these two formal acts gave Spain the exclusive rights to colonize all of the Western Hemisphere (excluding Brazil), including the exclusive rights to colonize all of the the west coast of North America.

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, p. 10: "Other pioneers have blazed the way for civilization by the torch and the bullet, and the red man has disappeared before them; but it remained for the Spanish priests to undertake to preserve the Indian and seek to make his existence compatible with a higher civilization."

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, p. 15: Due to the isolation of the Baja California missions, the decree for expulsion did not arrive in June of 1767, as it did in the rest of New Spain, but was delayed until the new governor, Portolà, arrived with the news on November 30. Jesuits from the operating missions gathered in Loreto, whereupon they left for exile on February 3, 1768.

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, p. 16

- ↑ James, p. 11

- ↑ Guest: "The blueprint for Alta California provided for a system of settlements significantly different from those in Baja California and Sonora. In their original design, both presidios and missions were different from their predecessors to the south. The plan to make the presidios agriculturally productive did not succeed. Neither did the plan for the mission-pueblos as racially integrated nuclei of urban centers, but the ideal of a closer association between "missionized" Indians and gente de razón, notwithstanding the opposition of the friars, was partially realized.

- ↑ Engelhardt, pp. 3-18