Tecum Umam

Tecum Umam (also Tecún Umán or Tekum Umam) was a legendary figure of Guatemalan and K'iche' history. Raised to the status of a national hero of Guatemala, celebrated by poets and invoked in ritual and festival contexts throughout the highlands, Tecum Umam is known as the defender of the K'iche' people and a symbol of indigenous resistance because of his role in the indigenous military resistance to the Spanish conquest of his homeland.

The legendary meeting of Tecum Umam and Pedro de Alvarado

The legend of Tecum Umam tells us that he commanded the thousands of K'iche' warriors who met the army of invading Spanish and indigenous warriors under Pedro de Alvarado on the plains of El Pinar in February of 1524. In the midst of the fray, Tecum Umam and Alvarado met face to face, each with weapon in hand. Alvarado was mounted on a horse and clad in armor while Tecum Umam wore the feathers of his nagual (animal spirit companion), the quetzal. A battle ensued that claimed the life of the K'iche' hero.

Taking to the sky in the form of an eagle, Tecum Umam struck down Alvarado's horse believing man and animal to be one and the same. He realized his error and turned for a second attack but Alvarado's spear pierced his opponent's chest and Tecum Umam fell to the ground dead. Then a quetzal landed on the fallen hero's chest, staining its breast feathers red with blood; the bright colors of the quetzal continue to remind us today of the great deeds of Tecum Umam.

This legend is often held to be largely apocryphal[1] but it is also widely assumed to ultimately be built around the actions of a real person.[2][3] Evidence to support both claims is found in a number of indigenous and Spanish documents that have surfaced over the years. The legend's absolute accuracy notwithstanding, Tecum Umam has inspired a wide variety of activities ranging from the production of statues and poetry to the retelling of the legend in the form of folkloric dances to prayers to the defender of the K'iche' for protection.

Tecum Umam's Legacy

National Hero

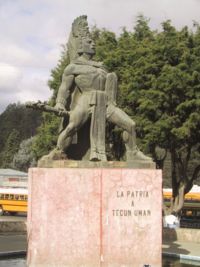

Tecum Umam was declared a National Hero of Guatemalan on March 22, 1960[3] and is the only figure to have earned that title. He is celebrated annually on February 20 and is memorialized by prominent statues in Guatemala City and Quetzaltenango. Tecum Umam's namesakes include a small town in the department of San Marcos on the Guatemala-Mexico border as well as countless hotels, restaurants, and Spanish schools throughout Guatemala.

Nobel laureate Miguel Ángel Asturias memorialized the K'iche' hero in a poem that bears his name.[4] Employing Asturias' characteristic use of themes borrowed from Guatemala's indigenous cultures and his unique style of magical realism, the poem finds the seeds of liberty in the person of Tecum Umam. The poem thus elegantly reflects the broader themes of Tecum Umam's heroic status as they are expressed through a national discourse that glorifies him as the common ancestor of all Guatemalans, the embodied fusion of Spanish and Maya.[5]

A bust of the K'iche' hero is also featured on the front of Guatemala's 0.50 Quetzal bill. To the left of Tecum Umam is the Resplendent Quetzal for which the currency is named. This is the national bird of Guatemala as well as the nagual of Tecum Umam. The bird's bright red chest and the elegant tail feathers are both significant in the legend outlined above.

Tecum Umam's presence on this bill places him in the company of some of the most important figures in Guatemalan history. He joins the ranks of other national heroes and founding fathers that are featured on Guatemala's currency, among whom are Justo Rufino Barrios, a military leader in his own right and president of Guatemala from 1873 until 1885; Mariano Gálvez, chief of state of Guatemala from 1831 until 1838; and Francisco Marroquín, an early defender of the rights of indigenous peoples.

Kíche' Hero

Tecum Umam is not only an official hero of Guatemala - he is also an important figure in a number of ritual and festival contexts within the indigenous communities of Guatemala. Among the best known of these contexts is the Baile de la conquista or "Dance of the conquest" that is performed in many Maya communities as a part of the celebration for the feast day of the town's patron saint. Costumbristas also evoke Tecum Umam in several ways as a part of traditional religious practice.

The confrontation between Tecum Umam and Pedro de Alvarado is the central theme of the Guatemalan version of the baile de la conquista[6] and acts as a symbol for the much larger conflict in which they were involved. The baile de la conquista of Latin America has its roots in the Baile de los Moros or "Dance of the Moors," which commemorates the expulsion of the Moors from Spain. As in other regions of colonial Latin America, priests encouraged the performance of the Baile de la conquista (which also ends in the religious conversion of the pagans) as a way to help them convert the population to Catholicism. In Guatemala, Tecum Umam takes the place of the Moorish prince from the Baile de los Moros. The dance reenacts the battle between the Spanish captain and the K'iche' prince while poking fun at the gawdy clothing and mannerisms of the conquistadors.

Tecum Umam is present as a powerful agent in a number of other ritual contexts as well. The activities leading up to the Baile de la conquista that are described by Ignacio Bizarro Ujpán[6] are characteristic of these broader practices. The sacerdote Maya, a Maya shaman, first invokes the name of God and then the village's patron saint, asking their forgiveness and explaining his (and his clients') purpose. Then, one by one, he calls on Tecum Umam or others from among a host of powerful figures (i.e. Maximón or in this case, Pedro de Alvarado) who are selected for their particular domains of influence. He offers them each tragos of alcohol and the smoke of copal, candles, and tobacco. Once he is satisfied that the benefactors are pleased with his offerings, the shaman explains why he has called on them, outlining specific needs or problems and asking for protection and good fortune on behalf of his clients and himself.

Photo © by Marco Palma, used by permission.

Did he ever actually exist?

Tecum Umam's status as either a man or a myth is a topic of lengthy and ongoing discussion. Historical research has demonstrated with some degree of surety that the man celebrated as a national hero of Guatemala probably did not exist quite as he is presented in the legend but there is also strong evidence to suggest that this character was not simply dreamed up.[2]

One piece of evidence comes from Alvarado himself in a letter written to Hernán Cortés. Others include a handful of indigenous and Spanish documents written in the years following the encounter. These are generally quite sparing in details, however - the legend in its current form appears to have come down to us from Francisco de Fuentes y Guzmán, who recorded it toward the end of the 17th century.

U b'i Tecum Umam - Tecum Umam's name

"Tecum Umam" was almost certainly not the proper name of the fallen K'iche' lord who Alvarado mentioned in his letter to Cortes, though it may have functioned as a sort of title. Ruud W. van Akkeren[2] provides several insights on this topic.

Sources

- ↑ Ronald W. Wilhelm. 1994. Columbus's Legacy, Conquest or Invasion? An Analysis of Counterhegemonic Potential in Guatemalan Teacher Practice and Curriculum. Anthropology and Education 25(3): 173-195.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ruud W. van Akkeren. 2004. Tecum Umam: ¿Personaje Mítico o Histórico? Paper presented at Ciclo de Conferencias 2004, Museo Popul Vuh, Universidad Francisco Marroquín

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 J. Daniel Contreras R. 2004. Dos guerreros indígenas. In El Memorial de Sololá y los inicios de la colonización española en Guatemala. J. Daniel Contreras R. and Jorge Luján Muñoz, eds. Pp. 65-76. Guatemala City: Academia de Geografía e Historia de Guatemala. ISBN 99922-737-1-2

- ↑ Miguel Ángel Asturias. Tecún Umán. Electronic document. Archived November 12, 2005.

- ↑ Carol Hendrickson. 1985. Guatemala - Everybody's Indian When the Occasion's Right. Cultural Survival 9(2):22-23.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 James D. Sexton. 1992. Mayan Folktales: Folklore from Lake Atitlán, Guatemala. ISBN 0385422539.