Baron Munchausen

- (This article is about the fictitious character Munchausen—single h, no umlaut; for the "real" Baron von Münchhausen, see Karl Friedrich Hieronymus, Freiherr von Münchhausen).

Baron Munchausen is an enduring figure of comical exaggeration, originated by Rudolf Erich Raspe in a series of stories that were first published in the 1780's (in German). Raspe himself may have borrowed the stories from others; and his own, regularly extended, collections of "Munchausen stories" were soon taken up and continued by later writers. In Germany, in Raspe's adopted homeland of England, and in selected areas worldwide, the stories became immensely popular, and the name of Munchausen became a synonym for any form of exaggerated story or "tall tale." In medicine, the term "Munchausen syndrome" came to refer to patients who concocted fictitious illnesses, usually of a nature that offered spectacularly intriguing diagnostic puzzles for their physicians, supported by elaborate false histories and feigned evidence in an effort for attention and hospitalization. In the twentieth century, the Baron was featured in films and animated cartoons, most notably in Terry Gilliam's 1988 film The Adventures of Baron Munchausen.

Raspe's Münchhausen

The actual Baron Münchhausen, a veteran of the Russian wars against the Turks, was well-known in European social circles for his entertaining accounts of his military exploits, and was said to be prone to exaggeration. A series of such droll tales were published name in the German periodical Vade Mecum für lustige Leute from 1781 to 1783; although their authorship is uncertain, several have been attributed to Rudolf Erich Raspe.[1] The Baron was not directly named in these stories, being referred to as "M-h-s-n" or "M," perhaps because of legal concerns.

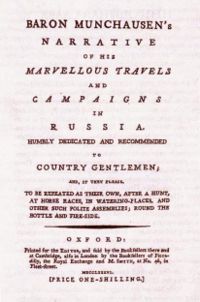

Legend has it that Raspe was once a guest of the Baron, who inspired him to pen the tales under Münchhausen's name (omitting one h in the process and spelling u for the original ü), but there is no evidence of their ever having met. The purported date of this meeting, 1775, was just before Raspe was discovered to have embezzled from a former employer, and fled Germany for England, where he was a member of the Royal Society. When news of his crime later reached England, Raspe was drummed out of the Society, and was forced to eke out a small living translating works from German for private parties, among them Horace Walpole, who took "poor Raspe" under his wing. It was around this time that he published, anonymously, Baron Munchausen's Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia in London at the end of 1785 (with publishing date given as 1786). It was a slender volume, with only five stories, two of which were translated from the Vade Mecum tales. They proved unexpectedly popular, and were reprinted, along with with several additional tales, as The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen in 1787. Raspe died in in 1793 while on a trip to Ireland, but his authorship of the Munchausen tales was not known until 1824, by which time they had already multiplied into numerous collections, some of which contained not one of Raspe's original tales.

One of the signature touches Raspe gave his Munchausen volumes was to reproduce an affidavit, purportedly signed by Lemuel Gulliver, Sinbad the Sailor, Aladdin, and the "Lord Mayor and Aldermen" of London, averring that everything in the book was absolutely true. Raspe may have imitated this from the opening of Lucian's True History, a similarly facetious tale which was a source for many stories in the Munchausen tradition.

Far from being honored by his newfound fame, the real Baron Münchhausen was said to have been dismayed; he disliked becoming well-known to the common rabble, and ceased holding dinner parties and social events. This dislike was picked up on by Terry Gilliam in his 1988 film, which opens with a scene where the "real" Baron accosts the actor representing him on the stage, declaring that the play is "all lies" and demanding an opportunity to set the record straight.

Later versions and parodies

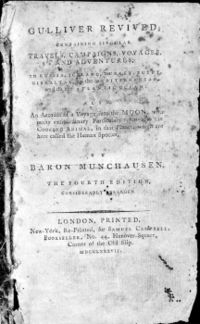

Additions to, and parodies of, Raspe's work began almost immediately; the very year after the first London edition, in 1786 when Gottfried August Bürger translated Raspe's tales into German, adding a few of his own. These were published as Wunderbare Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, Feldzüge und lustige Abentheuer des Freyherrn von Münchhausen ("Marvellous Travels by Water and Land: The Campaigns and Comical Adventures of Baron Münchhausen"). Munchausen made his American debut in 1805 with an anonymously-penned Gulliver Redividus . . . or, the Celebrated & Entertaining Travels and Adventures of the Renowned Baron Munchausen, Including a Tour to the United States. In 1819, an anonymous writer satirized Sir John Ross's recent polar expedition with a tract entitled Munchausen at the Pole, which awarded facetious laurels for Ross's achievements in retrieving such treasures as a "bucket of red snow" and a "button from a coat worn by Mungo Park." The best-known illustrations of Munchausen's exploits are those of Gustave Doré, first prepared for an edition of 1862, and frequently reprinted (see illustration above).

Film and animation

The first person known to have produced a film version of the Baron's exploits was Georgés Méliès, whose Les Hallucinations du Baron de Münchhausen appeared in 1911. In 1943, Josef von Báky filmed Münchhausen starring Hans Albers in the title role and Brigitte Horney as Katherine the Great. The production was supported by Josef Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, who was unaware that the screenplay had been written by Erich Kästner, who had been banned by the Nazis since 1933 for "decadent" art. It was filmed in Agfacolor, a German competitor of three-strip Technicolor, and was one of the earliest feature-length color films produced in Germany. 1962 saw The Fabulous Baron Munchausen, an animated feature film directed by Karel Zeman; while highly creative, the animation's overall quality was poor, and it is difficult to watch today. Terry Gilliam's The Adventures of Baron Munchausen in 1988 was the most ambitious version ever mounted, and was infamous for cost overruns and production problems. Nevertheless, it remains the best film version to date, with a fabulous turn by Canadian actor John Neville as the Baron, along with Eric Idle as his invaluable assistant "Berthold", Oliver Reed as Vulcan, Uma Thurman as Venus, and Sarah Polley as "Sally Salt." In addition to adaptations featuring the Baron himself, the Munchausen stories have also been recast in comics and animated cartoons featuring other self-aggrandizing heroes, ranging from John Randolph Bray's "Colonel Heeza Liar" (1913) to Jay Ward's Commander McBragg (1963).

Munchausen in medicine

In the English medical literature, Sir Richard Asher in 1951 was the first to describe and name Munchausen's Syndrome[2].He used this eponym because it reminded him of the fantastic imaginary adventures of an 18th century European aristocrat, the Baron von Munchausen. "Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always travelled widely; and their stories, like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful. Accordingly the syndrome is respectively dedicated to the baron, and named after him."[2]

"In the medical and dental literature, a number of reports have been published describing a Münchhausen syndrome in the German language and a Munchausen syndrome in the English language...The syndrome is defined as a condition characterized by the feigning of symptoms of a disease or injury in order to undergo diagnostic tests, hospitalization, medical or dental treatment."[3]

Although patients with Munchausen syndrome start out physically healthy, between self-injury, poisonings, and iatrogenic harm from interventions to treat the shammed medical illness, they may suffer severe bodily harm as a result of the syndrome. It is not unusual for Munchausen patients to make and purposefully infect and re-infect wounds, for example, and, in extreme cases, this leads not only to multiple scars, loss of function of body parts, but even to amputations. In the same spirit as the self-perpetuating spread of stories and legends in the literature and media devoted to Munchausen, Munchausen references in medicine have proliferated to include Munchausen syndrome, Munchausen-by-proxy, Veterinary Munchausen-by- proxy, and equally dramatic tales of truly ill patients dismissed as having Munchausen syndrome by their mistrustful physicians, who assumed that the unusual symptoms and histories of these patients were explained by fabrication rather than the actual situation of atypical or unusual manifestations of an undiagnosed primary disease.

Psychiatric illness

In 19XX, a formal psychiatric diagnosis of Munchausens was recognized. Some of its components are pseudologia fantastica. "Recovery from Munchausen syndrome is rarely reported. Most patients flee when confronted, perhaps only to repeat the deceptive behaviors elsewhere. Those who remain have only infrequently responded to psychotherapy."[4]

Although the great majority of patients with this syndrome are adults, there have been cases of older children and adolescents with the diagnosis. The recognition of such cases, minors who themselves cause injury or illness in order to play the part of the patient, has important consequences for parent. Ordinarily, when children have been found to be healthy despite elaborate evidence of serious illness, or the victims of repeated injury or purposeful poisoning or other bodily insult carried out in order to cause illness or symptoms that fit with an illness, these children are ordinarily assumed to be victims of Munchausen syndrome by proxy rather than their own psychiatric problems.[5]

Munchausen syndrome by proxy

"In 1975, Meadow described a serious form of child abuse, terming it Munchausen syndrome by proxy."[6] Most reported cases of Munchausen syndrome by proxy have concerned the parent, usually the mother, or other full-time caregiver who purposefully makes the dependent child ill in order to her or himself gain the attention of medical and nursing care givers. Some cases of Munchausen by proxy have resulted in the death of the child, and in families where one of the parents suffered from the need to play the role of the parent of the sick child, there have been deaths and serious illnesses of more than one child.

Although the victims of Munchausen syndrome by proxy always suffer some degree of harm from the parent's (or other adult's) manipulations, these manipulations themselves are not necessarily on the child. For example, although some caregivers have poisoned children with drugs that extend their bleeding time so that the child presents to the doctor with hemorrhages, other parents or caregivers have contented themselves with telling the doctor that the child has abnormal bleeding, perhaps when urinating- and then supplying that doctor with a urine specimen to which blood has been added. In either case, even when the manipulations themselves do not injure the child, if the parent is able to feign a condition convincingly enough, the child may undergo many invasive medical tests, be placed on all sorts of medications, and even undergo surgery.

The person perpetrating Munchausen by proxy also has a variant form of Munchausen syndrome, a serious psychiatric illness. There have been cases of suicide in caregivers who were confronted with their actions.[7]

Not all of the victims of Munchausen syndrome by proxy are children or even relatives. There have been cases of caregivers of adults who have been diagnosed with this psychiatric illness. In one such example, a hospital nurse whose patients fell ll because of her manipulations, there were multiple adults involved.[8]

Veterinary Munchausen's syndrome by proxy

The typical parent who fabricates a child's illness has reported to be female, usually the mother, although the finding of a father perpetrating the illness is not rare. However, recently, there have been reports of adults who poison or otherwise make ill both children and family pets, bringing them each to appropriate health services repeatedly for medical care. These cases have been predominantly male.[9] There have also been cases of Munchausen's syndrome by proxy in which only pets are involved, and in that situation no clear gender difference of the instigator of the symptoms has been reported.

As is cases of human victims, in veterinary Munchausen's syndrome by proxy, "the two most salient warning signs of factitious disorder by proxy are improvements in the victim's health during periods of separation and the deaths of those who have been under the perpetrator's care."[10]

References

- ↑ Dennis R. Dean, ‘Raspe, Rudolf Erich (1737–1794)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 29 May 2007

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Asher, R. (1951). Munchausen's Syndrome. The Lancet 1:339–341

- ↑ Reichart PA and Grote M. Munchhausen syndrome or Munchausen syndrome? Two names--one syndrome. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 30(8):510-2, 2001 Sep. UI: 11545245

- ↑ Feldman MD. Recovery from Munchausen syndrome. Southern Medical Journal. 99(12):1398-9, 2006 Dec. UI: 17236254

- ↑ Libow JA. Child and adolescent illness falsification. Pediatrics. 105(2):336-42, 2000 Feb. UI: 10654952

- ↑ Berg B. and Jones DP. Outcome of psychiatric intervention in factitious illness by proxy (Munchausen's syndrome by proxy). Archives of Disease in Childhood. 81(6):465-72, 1999 Dec. UI: 10569958

- ↑ Vennemann B., Perdekamp MG, Weinmann W., Faller-Marquardt M., Pollak S. and Brandis M. A case of Munchausen syndrome by proxy with subsequent suicide of the mother. Forensic Science International. 158(2-3):195-9, 2006 May 10. UI: 16169176

- ↑ Yorker BC. Hospital epidemics of factitious disorder by proxy. The Spectrum of Factitious Disorders. Edited by Feldman MD and Eisendrath SJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996, pp 157-17

- ↑ Finlay F. and Guiton S. Munchausen syndrome by proxy abuse perpetrated by men. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 79(5):466, 1998 Nov. UI: 10193271

- ↑ Feldman MD. Canine variant of factitious disorder by proxy. American Journal of Psychiatry. 154(9):1316-7, 1997 Sep. UI: 9286197