Chemical reaction

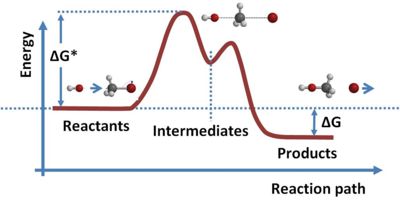

A typical reaction path. In this example, energy is released. See Bergmann et al.[1].

A chemical reaction is a process that transforms one set of chemical substances to another. The study of chemical reactions is part of the field of science called chemistry.[2]

Chemical reactions can result in molecules attaching to each other to form larger molecules, molecules breaking apart to form two or more smaller molecules, or rearrangement of atoms within or across molecules. Chemical reactions usually involve the making or breaking of chemical bonds, and in some types of reaction may involve production of electrically charged end products.

As shown in the figure for a general case, the participating reactants typically must surmount a threshold or activation energy to initiate the reaction, and intermediates exist briefly before the final products are formed. Such transformations potentially are accompanied by transfer of energy as heat, the so-called reaction enthalpy, and also changes in entropy describing the chaos exhibited by the distribution of reactants, intermediates, and products, and related also to energy through temperature. If a lot of heat is exchanged a lot of disorder may be stirred up, increasing entropy. These two factors are conveniently combined in the Gibbs free energy, a measure of energy actually available to participate in the reaction, which includes both the energy of the system due to its composition and that due to the distribution and amounts of the various components. In the figure the quantity ΔG* on the left indicates the change in Gibbs energy needed to surmount the activation threshold and ΔG on the right indicates the change in Gibbs energy when the reaction is complete, being the difference between the starting value of the reactants themselves and that of the final products. This overall change in Gibbs free energy may be made to do useful work, or simply be dissipated as heat.[3]

Chemical reactions can be either spontaneous[4] and require no input of energy, or non-spontaneous[4] which often require the input of some type of energy such as heat, light or electricity. Classically, chemical reactions are strictly transformations that involve the movement of electron in the forming and breaking of chemical bonds. A more general concept of a chemical reaction would include nuclear reactions and elementary particle reactions.

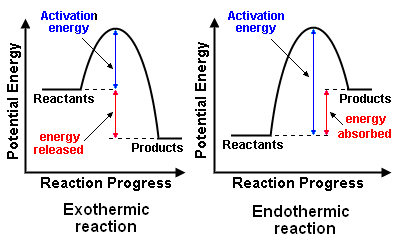

Energy changes in reactions

In terms of the energy changes that take place during chemical reactions, a reaction may be either exothermic or endothermic ... terms which were first coined by the French chemist Marcellin Berthelot (1827 − 1907). The meaning of those terms and the difference between them are discussed below and illustrated in the adjacent diagram of the energy profiles for exothermic and endothermic reactions.

Exothermic reactions

Exothermic chemical reactions release energy. The released energy may be in the form of heat, light (for example, flame), electricity (for example, battery discharge), sound and shock waves (for example, explosion) … either singly or in combinations.

A few examples of exothermic reactions are:

- Mixing of acids and alkalis (releases heat)

- Combustion of fuels (releases heat and light)

Endothermic reactions

Endothermic chemical reactions absorb energy. The energy absorbed may be in various forms just as is the case with exothermic reactions:

A few examples of endothermic reactions are:

- Dissolving ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) in water (H2O) (absorbs heat and cools the surroundings)

- Electrolysis of water to form hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) gases (absorbs electricity)

- Photosynthesis of chlorophyll plus water plus sunlight to form carbohydrates and oxygen (absorbs light)

Reaction types

The common kinds of classical chemical reactions include:[6][7][8]

- Isomerization, in which a chemical compound undergoes a structural rearrangement without any change in its net atomic composition (see stereoisomerism)

- Direct combination or synthesis, in which 2 or more chemical elements or compounds unite to form a more complex product:

- Chemical decomposition in which a compound is decomposed into elements or smaller compounds:

- Single displacement or substitution, characterized by an element being displaced out of a compound by a more reactive element:

- Metathesis or double displacement, in which two compounds exchange ions or bonds to form different compounds:

- Acid-base reactions, broadly characterized as reactions between an acid and a base, can have different definitions depending on the acid-base concept employed. Some of the most common are:

- Arrhenius definition: Acids dissociate in water releasing H3O+ ions; bases dissociate in water releasing OH− ions.

- Brønsted-Lowry definition: Acids are proton (H+) donors; bases are proton acceptors. Includes the Arrhenius definition.

- Lewis definition: Acids are electron-pair acceptors; bases are electron-pair donors. Includes the Brønsted-Lowry definition.

- Redox reactions, in which changes in the oxidation numbers of atoms in the involved species occur. Those reactions can often be interpreted as transferences of electrons between different molecular sites or species. An example of a redox reaction is:

- 2 S2O32−(aq) + I2(aq) → S4O62−(aq) + 2 I−(aq)

- In which iodine (I2) is reduced to the iodine anion (I−) and the thiosulfate anion (S2O32−) is oxidized to the tetrathionate anion (S4O62−).

- Combustion, a kind of redox reaction in which any combustible substance combines with an oxidizing element, usually oxygen, to generate heat and form oxidized products.

- Disproportionation with one reactant forming two distinct products varying in oxidation state.

- 2 Sn2+ → Sn + Sn4+

- Organic reactions encompass a wide assortment of reactions involving organic compounds which are chemical compounds having carbon as the main element in their molecular structure. The reactions in which an organic compound may take part are largely defined by its functional groups.

References

- ↑ Nikolaus Risch (2002). “Molecules - bonds and reactions”, L. Bergmann et al.: Constituents of Matter: Atoms, Molecules, Nuclei, and Particles. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-1202-7.

- ↑ Chemistry Explained Chemistry Encyclopedia

- ↑ For a qualitative discussion see, for example, John W. Moore, Conrad L. Stanitski, Peter C. Jurs (2009). “Coupling reactant-favored processes with product-favored processes”, Principles of Chemistry: The Molecular Science. Cengage Learning, pp. 633 ff. ISBN 0495390798.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Chemistry Tutorials: Entropy, Enthalpy and Spontaneous Reactions

- ↑ Paul Collison, David Kirby and Averil Macdonald (2002). Nelson Modular Science, Volume 2. Nelson Thorne Ltd.. ISBN 0-7487-6247-7.

- ↑ In the following chemical equations, (aq) indicates an aqueous solution, (g) indicates a gas and (s) indicates a solid. Superscripts with a positive sign (+) indicate an cation and superscripts with a negative sign (−) indicate an anion.

- ↑ H. Stephen Stoker (2006). General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry, 4th Edition. Brooks Cole. ISBN 0-618-60606-8.

- ↑ Mark S. Cracolice and Edward I. Peters (2009). Introductory Chemistry: An Active Learning Approach, 4th Edition. Brooks Cole. ISBN 0-495-55847-8.