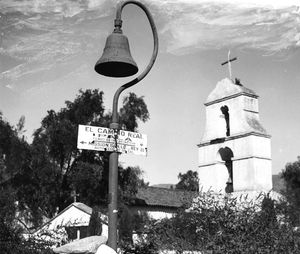

San Antonio de Pala Asistencia

The San Antonio de Pala Asistencia (or "Pala Mission" as it is known today) circa 1900. The structure is loosely styled after a similar one at the Mission of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe located in Juárez, Mexico.[1][2] The San Antonio de Pala Asistencia (or "Pala Mission" as it is known today) circa 1900. The structure is loosely styled after a similar one at the Mission of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe located in Juárez, Mexico.[1][2]

| |

| HISTORY | |

|---|---|

| Location: | San Diego County, California |

| Name as Founded: | Asistencia de la Misión San Luis, Rey de Francia [3] |

| English Translation: | Attendant to the Mission San Luis Rey de Francia |

| Patron Saint: | Saint Anthony of Lisbon, Portugal and Padova, Italy [3] |

| Founding Date: | June 13, 1816 [4] |

| Founded By: | Father Antonio Peyrí [3] |

| Military District: | First [5][6] |

| Native Tribe(s): Spanish Name(s): |

Payomkowishum Luiseño |

| Native Place Name(s): | Pale [7] |

| DISPOSITION | |

| Governing Body: | Roman Catholic Diocese of San Diego |

| Current Use: | Parish Church / Museum |

| Coordinates: | 33°21′40″N, 117°04′45″W |

| California Historical Landmark: | #243 |

| Web Site: | http://www.missionsanantonio.org/ |

The San Antonio de Pala Asistencia is a former religious outpost established by Spanish colonists on the west coast of North America in the present-day State of California. Founded on June 13, 1816 in what is today the Pala Indian Reservation in San Diego County (some twenty miles inland), the settlement served as an asistencia ("sub-mission") to nearby Mission San Luis Rey de Francia. The facility's official title is now Mission San Antonio de Pala.[4][8] Pala (a derivation of the native term Pale, meaning water) was essentially a small rancho surrounded by large fields and herds. The Pala site had been noted by Father Juan Mariner and Captain Juan Pablo Grijalva on an exploratory trip in 1795, when they went up the San Diego River, and then through Sycamore Canyon to the Santa Maria Valley (or Pamó Valley) and into what they named El Valle de San José, now known as Warner Springs. Once Mission San Luis Rey began to prosper, its existence attracted the attention of large number of mountain Indians, dubbed the Luiseños by the Spanish.

Precontact

History

The site for the Pala Mission was selected because it served as a natural gathering place for the native tribesman. Father Peyrí oversaw the addition of a chapel and housing to the granary complex that was constructed at the spot in 1810.[8] The chapel (whose interior wall surfaces featured paintings by native artists, and which today is the only mission facility still serving an Indian tribe) originally measured 144 by 27 feet. Workers went into the Palomar Mountains and cut down cedar trees for use as roof beams.[9] Pala is architecturally unique among all of the Franciscan missions in that it boasts the only completely freestanding campanile, or "bell tower," in all of Alta California. By 1820, some 1,300 baptisms had been performed at the outpost.[10] The Mexican Congress passed An Act for the Secularization of the Missions of California on August 17, 1833 (the Act was ratified in 1834).[11] Father Buenaventura Fortuna surrendered Mission San Luis Rey and all its holdings, including Las Flores Estancia and the Pala Asistencia, to government comisianados (commissioners) Pío Pico and Pablo de la Portillà on August 22, 1835; the assessed value of "Rancho de Pala" was $15,363.25.[12] Fearful of the impending "conquest" of California by the United States, Pico sold off all of the holdings (including Pala) to Antonio J. Cot and José A. Pico on May 18, 1846 for $2,000 in silver and $437.50 in wheat (the sale was later declared invalid by the U.S. Government).[10] Through the years, priests from San Luis Rey continued to visit Pala and conduct baptisms, marriages, and worship services.

On Christmas Day, 1899 the San Jacinto Earthquake shook the Pala Valley, causing the rook over the church sanctuary to collapse.[13] In 1902, a group calling itself the "Landmarks Club of Southern California" (under the direction of acclaimed American journalist, historian, and photographer Charles Fletcher Lummis) purchased Pala Mission. The following year, the Club returned ownership to the Catholic Church and "...saved the Chapel and a few rooms from complete ruin with a timely work of partial restoration...".[14] Pala is alone among the California missions in that it that has ministered without interruption to the needs of the Indians for whom it was originally built since its inception.[13] It is also the only sub-mission still intact. The traditional Corpus Christi Fiesta has been celebrated every year since its founding. Though it lacked a resident priest, Pala nonetheless served as the "mother" mission to chapels in Cahuilla, La Jolla, Pauma, Pichanga, Rincon, Santa Rosa, and Temecula.[15] On August 9, 1942 MGM motion picture actress Ruth Hussey was wed at Pala Mission. In 1948 the Verona Fathers (Sons of the Sacred Heart) succeeded the Franciscans in the care of the Mission.[16] Six years later, the fathers undertook a complete restoration of the Mission. In May, 1991 administration of the Mission reverted to the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Diego, and since June of 1996 the Barnabites|Barnabite Fathers have held charge over the Mission's affairs.

Mission bells

Bells were vitally important to daily life at any mission. The bells were rung at mealtimes, to call the Mission residents to work and to religious services, during births and funerals, to signal the approach of a ship or returning missionary, and at other times; novices were instructed in the intricate rituals associated with the ringing the mission bells. Pala's bells are the same ones that have been calling the Indians to prayer since 1916. American academician, architect, and author Rexford Newcomb published design studies of the original bell tower in his 1916 work The Franciscan Mission Architecture of Alta California.[17] Ironically, the structure was completely destroyed by torrential rains later that same year; a precise replica was erected immediately thereafter and today stands in its place. The structure measures some 35 feet above the base (which itself is 15 feet off the ground) and supports two bells, each hanging from a rawhide tether.

The large bell, set in the lower embrasure, bears inscriptions in Latin and Spanish as follows (translated into English):

- "Jesus, Redemptor of Mankind [IHR] Holy God, Holy Mighty One, Holy Immortal One, Have Mercy on us. Year of our Lord 1816" (upper band);

- "Cervantes made us." (middle band); and

- "[In honor of] Our Seraphic Father, Francis of Assissi, San Luis King, Saint Clara, Saint Eulalia, Our Light" (lower band).

The smaller bell, mounted in the upper opening, reads (in Latin):

- "Jesus + Maria" (upper band); and

- "Santus Deis, Santus Fortus, Santus Immortalis" and "Micerere nobis" (lower band).[18]

Folk tales about the mission all include mention of a prickly pear cactus (the symbol of Christian victory) that grew up at the foot of the cross.[19]

Notes

- ↑ Carillo, p. 16

- ↑ (PD) Photo: J.C. Parker

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Ruscin, p. 153

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Leffingwell, p. 32

- ↑ Forbes, p. 202

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. v, 228: "The military district of San Diego embraced the Missions of San Diego, San Luis Rey, San Juan Capistrano, and San Gabriel..."

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 195

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Carillo. p. 7 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "carillo7" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Carillo, p. 8

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Leffingwell, p. 33

- ↑ Yenne, p. 19

- ↑ Carillo, p. 9

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Carillo, p. 11

- ↑ Carillo, p. 33

- ↑ Carillo, p. 39

- ↑ Carillo, p. 12

- ↑ Newcomb, pp. 58-59; 61

- ↑ Carillo, pp. 17-18

- ↑ Carillo, p. 18