Paris, Tennessee

Authors [about]:

join in to develop this article! |

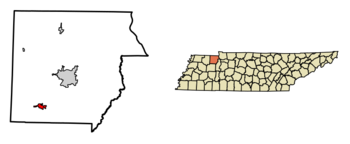

Paris, Tennessee (USA) is a small town of about 10,000 people in West Tennessee in the Unites States of America. Paris is the county seat of Henry County (which has 32,363 residents in 2021, including Paris[1]).

Geography of the town and county

Henry County is in the upper right corner of West Tennessee; its northern border is the Tennessee-Kentucky state line, and to its south are Carroll and Benton Counties. To the west, the border is Weakley County and the eastern border of the county is a combination of the former Big Sandy river route and the Tennessee River.

Streams and rivers on the on the western side of Henry County flow into the North and South Forks of the Obion River; this is the side of the county that had most of the cotton and tobacco farms in the past.

Streams on the eastern side of the county flow either directly into the Tennessee River, or first into the Big Sandy River, a tributary of the Tennessee. The Big Sandy is 67 miles long and merges into the Tennessee River (now expanded as Kentucky Lake) at the border of Henry and Benton counties. In the 1930's, TVA rerouted the Big Sandy river from its meandering delta-river flow into a straight-cut ditch. The southeast county border retains the winding shape of the former Big Sandy river.

Economy

As of 2021, the county and town are struggling economically. The poverty rate of around 20% is more than twice the national average[2].

Other placeholders, to be situated in this article later on

The heart of downtown Paris is the court house built in 1897[3]. On the court house lawn is a statue of a confederate soldier[4], one of many monuments around the U.S. earmarked by the InvisibleHate.org website in 2020 as appropriate for removal (possibly to a less prominent location such as a private cemetery containing the remains of confederate soldiers).

In August of 2020, the Lee Academy for the Arts (402 Lee St.) was renamed as Paris Academy for the Arts, and its board of directors (formerly called the Robert E. Lee School Association) renamed itself as the Paris Academy Association. The site and building had born the name of confederate general Robert E. Lee for well more than a century.[5]

This is the reference for Van Dyke[6]. This reference is currently a placeholder and will be placed on the first occurrence when this article is near completion.

Image gallery

These will be placed later

History of the town and county

The town was founded and incorporated in 1823.

Before 1800

Takeover by Europeans (1800-1840)

== Life of settlers before the Civil War (1820-1860)

Early schools

In the early 1800's when Paris was first founded, wealthier people sent their boys to private academy. Some girls also got "academy" (but modified, excluding classics and including more home-making/arts). Anyone else got so-called "common schools", if at all. Common schools arose which taught basic reading writing arithmetic to no more than 8th grade.

Even some slaves were given a basic education (taught to read, maybe). Free negroes, on the other hand, were not allowed to hold jobs, associate with slaves (or anyone besides other free negroes), and were not allowed to attend school at all.

Early economy, demographics, and slavery

The following rates were paid for slaves in Henry County during a sale in February 1839:[7]:

- man: $900 to $1000

- woman: $700 to $900

- child: $600 to $800

In terms of 2021 monetary worth, the cost per slave would be:[8]

- man: $25,209 to $28,010

- woman: $19,607 to $25,209

- child: $16,806 to $22,408

It is important to realize that slave-owners had invested substantial funds in their source of labor and believed that abolition of slavery would ruin the economy and way of life. Their participation in the civil war for the South was in every way an attempt to protect against having their right to own slaves infringed. The struggles for and against slavery throughout the thirty years leading up to the civil war were apparent in almost all parts of the Southern states, as well as the newly added territories, where the questions were twofold: Would slavery be allowed in this new territory, and would the new territories have to return escaped Southern slaves to their masters?

In the 1850s, the decade leading up to the civil war, most of the economy of Henry County came from moderate-sized farms between 20 and 500 acres; their owners and families were the main demographic of the county at that time.[9]. Three other groups existed in small pockets only: large plantation owners, poor whites, and free negroes. Per the county census figures, a third of all heads of these farm families owned slaves in 1850. Tobacco and cotton were important crops, and the labor for those crops was done almost exclusively by slaves, who constituted a quarter of the overall population, but lived on only a third of the farms[10]. The county's slaveholders had great influence with politics of the day. Two-thirds of Henry County voters elected to secede from the union, and any Union sentiment in the remaining third of the population was brutally suppressed[11], not only in Henry County but in most of West and Middle Tennessee. During this period, Isham G. Harris and John D. C. Atkins, both strongly pro-southern in sentiment, were very popular and acted as the main political voices in Henry County[12].

In 1860, Henry County’s two largest landowners were William A. Tharpe (4938 acres) and J. J. Cooke (2590 acres). They were likewise holders of the most slaves, 94 and 77 respectively[13]

During the Civil War (1860s)

After the Civil War (1870 - 1930)

Factories (1930s to 2000): Boom and bust

For a period from the 1930's through the 1980's, Paris and Henry County became a source of cheap labor for factories of various companies. This caused a migration of rural farmers from the countryside into the town of Paris in order to work in the factories. It was typical, at first, that only white men were employed in these factories. During WW II, a shortage of men due to the military draft gave white women their first opportunities at factory jobs. Although after the war, the women initially lost some of those jobs due to the return of men from the war, by the 1960's and 1970's, social changes led to many more factory jobs opening up for women, although they were typically relegated to the office or to the lower paying, more tedious jobs.

During the late 1950s, a major change started rattling the manufacturing industry in the U.S. Many manufacturers who had once made their products on American soil began moving their production overseas. By moving overseas, companies could make and ship parts to the U.S. more cheaply than they could manufacture them in the U.S. By the 1980's, almost all factories had been moved out of the U.S.

This section wlists some industries that were active in Henry County during the twentieth century. Most, if not all, are now defunct.

The Clippard Plant

Clippard Instruments, Inc. opened a factory in Paris, Tenn. in 1955 after its previous factory in Sturgis, KY, developed labor problems[14]. Clippard leased a 30,000 square foot facility in Paris, TN, and converted it into a semi-automated assembly plant to make radio and television components such as the electronic coils. The Clippard plant employed about 100 employees and operated in Paris until 1973[15].

One reason that the plant may have closed is that the demand for coils was decreasing as radios and TVs began to be built using transistors, which meant that the need for vacuum tubes, and therefore coils, decreased substantially. Another likely reason was the creation of trade agreements with other countries. The U.S. tariff on imported coils had been reduced from 15% to 7.5% during the Kennedy administration in the 1960's. This reduction in tariff was implemented over five years, from 1968 to 1972. Clippard closed the Paris, TN. plant in November 1973, stating that it could not operate that plant profitably in competition with lower cost imports. A third possible reason for loss of the plant was the availability of cheaper labor elsewhere. After closing the Paris plant, Clippard transferred its coil-manufacturing materials and equipment to a factory in Matamoros, Mexico, that was opened in 1972. An April 1974 report funded by the U.S. Government found that, as a result of concessions granted under trade agreements such as Section 301(c)(2) of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, more electronic coils were being imported in the U.S., which caused American workers employed by Clippard Instruments, Inc. to lose employment.[16]

Salant and Salant: the "shirt factory"

This garment factory on Washington Street in Paris, TN, opened in the 1930s and operated until at least the 1960's. It employed mainly women to do the sewing and men as supervisors and managers. In the late 1950's and early 1960's, it also began employing some people of color. The production floor was a huge open space with ceiling fans (there was no air conditioning in those days), with many long rows of sewing machines. Work conditions were reputed to be hard; workers had to "make production" every day, which meant they had to produce an amount specified by management, or else they would be fired. Pay was low, conditions harsh, and yet, these jobs were highly sought after within the community because it was one of the first places that women could obtain work outside the home.

Holley Carburetor

In 1949, Paris Manufacturing Co. built a factory on Highway 69, northwest of Paris, and leased it to Holley Carburetors, who bought the building outright in 1958. Holley Carburetors operated the plant in 1987, and when it closed, about 1000 jobs were lost. The Holley plant was unionized (UAW); the year before the closing, the union had voted to refuse to build fuel injection devices, and possibly as a direct result of this vote, the entire plant was shut down with all jobs lost.

Emerson Electric

Midland Ross

Markel Lighting

This lamp factory located near the fairgrounds operated during the 1970's and 1980's. Ceramic lamp bases were molded, fired, painted, decorated, and assembled into lamps, which were packed and then sent to commercial lamp outlets. The factory was not air conditioned. It employed both men and women, perhaps a hundred people[17].

1960's and Desegregation

Prior to about 1962, schools in Paris and Henry County were segregated. Beginning around the fall of 1962, schools began a gradual process of introducing selected students of color into the white schools, and by around 1969, the gradual process of combining schools was completed when a new high school (Henry County High School) opened up in the center of the county, in Paris. All students from all over the county were transported to the new, consolidated school without regard for race. A similar process played out at other age levels. Many of the smaller, remote, rural schools were forced to close and send students to consolidated schools in Paris. Prior to 1969, black high school students attended Central High School, a segregated school, and school children of all ages attended segregated schools. No online history of segregation for the town and county seems to exist; current web pages read as if segregation never existed.

During the same span of years, a gradual process of desegregation began taking place in other aspects of the town and county, not just in schools. For example, prior to this time, people of color going to see a film at the old Capitol Theater in Paris were required to enter by a side door and sit in a gallery separate from white people, and incidentally farther from the screen. Also, people of color were not allowed to eat in the same restaurants as white people (prior to the 1960's). There was some friction as these things began to change, and the black people faced continual low-grade opposition and some abuse, but the integration did continue. Also prior to the 1960's, black people were not welcome in the main part of town except possibly on a few occasions such as Mule Day (which was eventually replaced by the World's Biggest Fish Fry). And finally, people of color were never hired for most jobs. The only work for most black men (and most women or children too) was picking cotton. Women were sometimes hired as cooks, housekeepers or nannies in white households and white-owned restaurants, but they had to remain out of sight and out of mind or they would be fired. As racial issues played out nightly on TV screens, the people of Paris slowly made their own peace without major demonstrations or public incident.

Even throughout the 1970's, black men were seldom (if at all) hired for factory jobs.

Within the factories, white women began to be hired by the 1960's but often found themselves relegated to the lower-paying jobs.[18]

References

- ↑ Henry County, Tennessee Population 2021 on World Population Review, last access 1/27/2021

- ↑ Henry Co., TN, Population Data Profile, last access 2/15/2021

- ↑ Per the National Geographic Tennessee River Valley website (last access on 11/30/2020), the 1897 Richardsonian Romanesque court house in Paris is the oldest working judicial building in West Tennessee.

- ↑ Waymarking: Henry Co. Confederate Monument, Paris, TN, last access 1/17/2021

- ↑ The PI (Paris Post-Intelligencer) Aug 28, 2020 article PARIS, TN: Former Lee school building gets name change, last access 2/15/2021

- ↑ Antebellum Henry County by Roger Raymond Van Dyke, West Tennessee Historical Society, Papers 1947-2015, Vol 33, 49pp; see page (tbd)

- ↑ WTHS Van Dyke p73

- ↑ https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1839?amount=1

- ↑ WTHS, Van Dyke p 72

- ↑ WTHS, Van Dyke pp69-71

- ↑ WTHS Van Dyke, p 73 and p 78

- ↑ WTHS Van Dyke, p 74

- ↑ Chase Mooney, “Slavery in Tennessee”, 1957, Indiana University Press, Bloomington; 199pp as cited by Van Dyke p 25, footnote # 69

- ↑ Clippard History - 1950's, last access 4/13/2021

- ↑ Publication 664, April 1974 of the U. S. Tariff Commission, last access 4/12/2021

- ↑ Publication 664, April 1974 of the U. S. Tariff Commission, last access 4/12/2021

- ↑ This is all based on my memory. My mother and brother both worked there for several years; my neighbor worked there; and I worked there for one summer during my college years in the 1970s.

- ↑ Much of the information in this entire section is based on my personal memory of having grown up in Paris, TN, and attended the schools from 1958 until 1971. Pat Palmer