David Hume

David Hume (April 26, 1711 – August 25, 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, economist, and historian. He is considered one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and the Scottish Enlightenment. Although in recent years interest in Hume's work has centred on his philosophical writing, it was as an historian that he first gained recognition and respect.

Biography

Hume was born in Edinburgh, on the 26th April 1711, the second son of a middle-class country family who lived in the south of Scotland. His father, Joseph Hume (or Home), was owner of Ninewells, a small estate in Berwickshire. David was the youngest of three children, who after the death of the father in 1713 were brought up by their mother, Fatherine, the daughter of Sir David Falconer, president of the college of justice, and a staunch Calvinist. She survived until 1749, long enough to see the fame of the younger son securely established. "Our Davie," she is widely quoted as saying, "Our Davie’s a fine good-natured crater, but uncommon wake-minded." Whether by "wake-minded" she meant "weak-minded" or "alert" is unclear.[1]

David Hume studied at the University of Edinburgh for three to four years, left at age sixteen in preparation to become a lawyer, but soon gave that up. Two years later he had a nervous breakdown from his uninterrupted and passionate study of philosophy, and after recovering went to France for three years to write a book he published anonymously; A Treatise of Human Nature. It wasn't very well received at the time and Hume, having failed to make an impact in London retired to his family home for the next eight years, producing at that time his volume of Essays. There were better received, but Hume's criticism of religion prevented him from becoming a professor of philosophy in Edinburgh in 1744. His convictions also prevented him from advancement in Glasgow years later.

In the following years Hume spent time tutoring a nobleman who was later certified as insane. However, Hume's prospects improved. He became secretary to a general who led a military expedition to the French coast and shortly after a secret mission to Vienna and Turin. These posts made Hume wealthy and he returned to Scotland, living comfortably with his brother and then, in Edinburgh, with his sister. During the next fifteen years he wrote his major works; The two Enquiries, the remainder of his Essays, two books on religion and the six volumes of the History of England.

From 1763 to 1766 he served as secretary to the British ambassador in Paris. Returning to London, he was appointed Undersecretary of State. He resigned two years later as a result of poor health and spent the rest of his years in Edinburgh, revising his essays, conducting a large correspondence with many distinguished friends and became increasingly famous as an essayist and historian.

Philosophy

Like John Locke and George Berkeley, Hume was an empiricist - that is to say that he believed knowledge is derived from experience rather than reason. He had little time for metaphysical a priori explanations ("hypothes[es], which can never be made intelligible") but attempted to construct a "science of human nature" in the Treatise and the Enquiry. He held that little knowledge can be gained by deduction from ideas, and as the causal interactions of physical objects are merely uncertain matters of fact, he argued that our belief that they exhibit any necessary connection can never be rationally justified, and he concluded that a severe skepticism is the only defensible view of the world. He argued that we cannot even rationally justify our beliefs in the reality of the self, or the existence of an external world.

In An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding Hume defines “moral philosophy” as “the science of human nature,” and distinguishes “two different manners” in which it has been pursued by philosophers. The first manner, reflecting positions taken in Hume's time by Shaftesbury and Francis Hutcheson, regards humans as active creatures, driven by desires and feelings and “influenced…by taste and sentiment,” seeking some things and avoiding others according to their perceived value.

The second manner is to regard humans as reasonable creatures, and aims “to find those principles, which regulate our understanding, excite our sentiments, and make us approve or blame any particular object, action, or behaviour.” They seek to discover hidden truths that will “fix, beyond controversy, the foundations of morals, reasoning, and criticism.”

Hume's approach to discovering “the proper province of human reason” is skeptical and critical.

"Accurate and just reasoning is the only catholic remedy, fitted for all persons and all dispositions, and is alone able to subvert that abstruse philosophy and metaphysical jargon, which being mixed up with popular superstition, renders it in a manner impenetrable to careless reasoners, and gives it the air of science and wisdom."

Hume the atheist

"There Aikenhead was hanged for a piece of boyish incredulity ; there, a few years afterwards, David Hume ruined Philosophy and Faith, an undisturbed and well-reputed citizen ; and thither, in yet a few years more, Burns came from the plough-tail, as to an academy of gilt unbelief and artificial letters." (Robert Louis Stevenson[2]

The Edinburgh that Hume lived in was still emerging from the rigid Calvinism of John Knox, a Protestant fundamentalism that in 1697 had seen a young student, Thomas Aikenhead hanged in public for blasphemy for expressing atheist opinions in private conversation. Hume though, was openly known for his atheism, and was well tolerated, in the spirit of the Scottish Enlightenment that encouraged questioning in all things. While supervising the building of his house in Edinburgh's New Town, Hume often took a short cut to the New Town that took him across a bog - the Nor' Loch bog. On one trip he slipped and fell in. He was seen by an old fishwife who, recognising 'Hume the Atheist' refused to help him unless he would repeat the Lord's Prayer. Hume complied, and was duly rescued, and thereafter claimed that the Edinburgh fishwife was the most acute theologian he had ever met.[3]

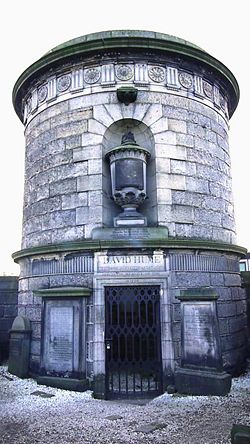

Hume died from bowel cancer, maintaining his atheism to his last breath. He is buried on the eastern slope of Calton Hill, overlooking his home at No.1 St David Street, in Edinburgh's New Town; his tomb bears the epitaph that he wrote for himself: "Born 1711, Died [----]. Leaving it to posterity to add the rest." The night after Hume's funeral, it is reported that some of the crowd crouched behind the gravestones, to see if the devil would come to carry off his soul.

|

"I am, or rather was (for that is the style I must now use in speaking of myself, which emboldens me the more to speak my sentinients),—I was, I say, a man of mild dispositions, of command of temper, of an open, social, and cheerful humour, capable of attachment, but little susceptible of enmity, and of great moderation ill all my passions. Even my love of literary fame, my ruling passion, never soured my temper, notwithstanding my fre-quent disappointments. My company was not unacceptable to the young and careless, as well as to the studious and literary; and as I took a particular pleasure in the company of modest women, I had no reason to be displeased with the reception I met with from them. In a word, though most men anywise eminent have found reason to complain of calumny, I never was touched, or even attacked, by her baleful tooth; and, though I wantonly exposed myself to the rage of both civil and religious factions, they seem to be disarmed on my behalf of their wonted fury. My friends never bad occasion to vindicate any one circumstance of my character and conduct; not but that the zealots, we may well suppose, would have been glad to invent and propagate any story to my disadvantage, but they could never find any which they thought would wear the face of proba-bility. I cannot say there is no vanity in making this funeral oration of myself, but I hope it is not a misplaced one and this is a matter of fact which is easily cleansed and ascertained." David Hume [4] |

References

- ↑ David Hume Compossível História da Filosofia

- ↑ Edinburgh Picturesque Notes RL Stevenson, 1879; see also Thomas Aikenhead and Robert Burns

- ↑ Cited in Ramsays Reminiscences of Scottish Life and Character (Project Gutenberg) "There is a story traditionary in Edinburgh regarding David Hume, which illustrates this feeling in a very amusing manner, and which, I have heard it said, Hume himself often narrated. The philosopher had fallen from the path into the swamp at the back of the Castle, the existence of which I recollect hearing of from old persons forty years ago. He fairly stuck fast, and called to a woman who was passing, and begged her assistance. She passed on apparently without attending to the request; at his earnest entreaty, however, she came where he was, and asked him, "Are na ye Hume the Atheist?" "Well, well, no matter," said Hume; "Christian charity commands you to do good to every one." "Christian charity here, or Christian charity there," replied the woman, "I'll do naething for you till ye turn a Christian yoursell'--ye maun repeat the Lord's Prayer and the Creed, or faith I'll let ye grafe there as I fand ye." The historian, really afraid for his life, rehearsed the required formulas."

- ↑ quoted in David Hume, article in the 1902 edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica