Gertrude Bell

Gertrude Margaret Lothian Bell (1868-1926) was an English author, "traveller" and political officer who influenced the formation of Iraq, when, in 1932, that state gained independence from the United Kingdom. At a memorial service for her in 1927, at the Royal Geographic Society, she was called the most powerful woman in the British Empire after the First World War, the "uncrowned queen of Iraq", and possibly the brains behind T. E. Lawrence and the definer of Mideast policy for Winston Churchill.[1] In her day, especially for a woman, "traveller" had some of the flavor of "special operations" today.

Her intellect became obvious in childhood, and she constantly challenged herself. She prepared systematically for her travels, developing excellent language and cross-cultural skills. By 1905, she was providing information previously unknown in Europe.

She had met David Hogarth in 1899; he was to be both a friend and mentor, and guide of British policy. Hogarth was also a mentor to Lawrence, whom Bell met in 1911, saying "An interesting boy; he will make a traveller." She met him on an archaeological site where she had hoped to find Hogarth; Lawrence wrote of her to Hogarth, "Gerty has gone back to her tentsto sleep. She has been a success and a brave one."[2]

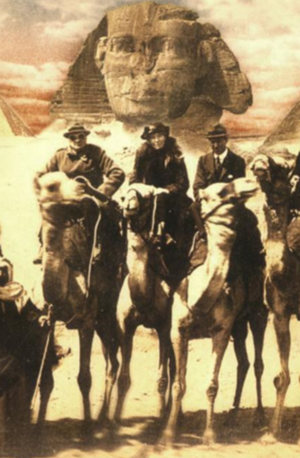

A 1921 photograph shows some of her later influence, as well as personalities. Taken on 22 March, the

last day of the Cairo Conference and the final opportunity for the British to determine the postwar future of the Middle East. Like any tourist, the delegation makes the routine tour of the pyramids and have themselves photographed on camels in front of the Sphinx. Standing beneath its half-effaced head, two of the most famous Englishmen of the twentieth century confront the camel in some disarray: Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill, who has just, to the amusement of all, fallen off his camel, and T. E. Lawrence, tightly constrained in the pin-striped suit and trilby of a senior civil servant. Between then, at her ease, rides Gertrude Bell, the sole delegate possessing knowledge indispensable to the Conference. Her face, in so far as it can be seen beneath the brim of her rose-decorated straw hat, is transfigured with happiness. Her dream of an independent Arab nation is about to come true, he choice of a king endorsed: her Iraq is about to become a country. Just before leaving the hotel that morning, Churchill has cabled to London the vital message "Sharif's son Faisal offers hope of best and cheapest solution.[3]

There are eerie parallels to today's situation in Iraq "...Faisal, the protege of Bell and T. E. Lawrence (better known as Lawrence of Arabia), was imported from Mecca to become the "roof." In early 2004, David Ignatius wrote in the Washington Post about the offer of Prince Hassan of Jordan, the great nephew of Faisal, to mediate among Iraqi religions factions to bring them together and become a "provisional head of state."[4]

Early life

Her mother died when Gertrude was three, after her brother Maurice's birth. This increased her bonds with her father, Hugh. She was a literate child; in the first known letter, written when she was five, she told her grandmother, "My dolls have given me great amusement. You wer very good to get them for me." Her governesses found her a "handful". Her father remarried when she was eight, and she formed an excellent relationship with her stepmother, Florence Oliff.

She led her brother Maurice into endless adventures, with Maurice often falling from walls while Gertrude landed gracefully, a foretaste of her later mountaineering. Unusually for a girl in the late 19th century, she went to Queen's College in Harley Street, first as a day scholar living with her maternal grandmother, and then as a boarder. She was emphatic about the studies she liked and disliked, and rejected music and Scripture. [5]

University

The Bell family had been growing in status during her girlhood, opening opportunities. [6]

She enrolled at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, in 1886.[7]

While women still could not receive degrees at Oxford, she did earn a "First" at Oxford, in Modern History. No woman had previously won first-class honors in any field.

Surprisingly to modern eyes, Bell, and other influential women of the time, opposed womens' suffrage.

Educational travel

Within the culture of the time, however, she was an apparent failure, as no one had asked for her hand in marriage. [8]

Romania

To correct her perceived failings, family friends, the Lascelles family, invited her to spend the winter season of 1889 in Bucharest, Romania. Whatever this may have done for her social life, it was her introduction to the diplomatic world, and to Turkey and the Ottoman Empire.

Persia

Travel was an acceptable second chance, in the times, to find a husband. Before traveling to Persia, however, she studied Farsi and gained conversational and reading knowledge. [9] In 1892, she journeyed to visit an uncle, who was then the British Ambassador to Persia, stationed in Tehran. She was impressed with a young diplomat, Henry Cadogan, with whom she had both an emotional and intellectual connection, with whom she could "talk vigorous politics." His income, however, was small.[10] When he asked her father for her hand in marriage, but was refused. Cadogan died of cholera in 1893. [11]

She continued her Farsi studies, using French with a native tutor. Upon her return in 1894, she published a small book, calledd Safar Nameh i.e., Persian Pictures." This was followed by a translation of the Divan of Hafiz in 1897. Lady Bell observes the breadth of her standards of comparison: "She draws a parallel between Hafiz and his contemporary Dante: she notes the similarity of a passage with Goethe: she compares Hafiz with Villon, on every side gathering fructifying examples which link together the inspiration of the West and of the East."

Europe

In April 1893, she spent time in Weimar, studying German, and then returned to Britain until 1896. Lady Bell reports no surviving letters until 1896, when she spent some time in Italy, again studying the language.

Jerusalem and environs

After an around-the-world trip, in November 1899 she journeyed to Jerusalem. Lady Bell said she intended to learn more Arabic, arranging studies "Dr. Fritz Rosen was then German Consul at Jerusalem. He had married Nina Roche, whom we had known since she was a child, the daughter of Mr. Roche of the Garden House, Cadogan Place. Charlotte Roche was Nina's sister. " She found Arabic difficult, but continued to study 4-6 hours per day. With the Rosens, she had her first contact with the Druze. [12]

Mountaineering

While she loved the desert, mountains challenged her as well. She traveled to Switzerland in 1900 and 1902, doing increasingly difficult technical rock climbing. Mountain climbing was considered acceptable for women at the time, but she took on exceptionally hard climbs. Her professional guide, Ulrich Furher, said "had she not been full of courage and determination, we would all have perished. Of all amateur climbers, men and women, he had known, very few surpassed herin technical sno one came to her standard in "coolness, bravery and judgment."[13]

Developing world experience

Traveling to India, and then the Pacific, she had an important first meeting with the British consul in Muscat, Percy Cox, learning of details of tribal struggle in the Arabian peninsula, and determining to explore it. As part of preparation, in 1905, she undertook private tutoring in archeology with Salomon Reinach, and discussed Arabia with her friend David Hogarth, whom she met socially in 1899 but who became a mentor. Hogarth advised her it was premature for her to journey there, and she returned to the Jordan Valley for more serious archeological study. She took guns and maps, prohibited by the Ottomans. She bonded with the often secretive Druze, who sought alliance with Britain, but also formed friendships with Turkish officials.

Her first book, The Desert and the Sown, was finished in 1906. While many Europeans simply dismissed the "natives", she understood some key concepts, explicitly saying that "Syria" was a European construct:

Islam is the bond that unites the western and central parts of the continent, as it is the electric current by which the transmission of sentiment is effected, and its potency is increased by the fact that there is little or no sense of territorial nationality tgo counterbalance it. A Turk or a Persian does not think or speak of "my country" [as does a Western European]...his patriotism is confined to the town in which he is a native, or at most the district in which that town lies."[14]

|

One of the drivers of British policy came with the technological revolution in the Royal Navy, as ship power plants changed from coal to oil. HMS Dreadnought (1905) already had been a leap forward in gunnery and speed; she had dual oil and coal propulsion. Newer vessels, however, were exclusively oil, and Britain needed to secure oil to maintain naval dominance. As a result, Churchill, in 1912, committed to a major British share in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, based around Basra. |

First journey to Mesopotamia (Iraq)

After spending most of 1907 and 1908 in England, she arrived in Beirut in February 1909, and followed the Euphrates River to the Shatt-al-Arab. This, in fact, was her first trip that went beyond archeology, but produced strategically accurate geographic information.[15] In later histories of the Arab Revolt, there are many references to her maps.

While women did not have authority in most of the tribal societies, a European woman was so unusual that she was more outside the rules in the Muslim groups than with her countrymen.

Intelligence

Hogarth had urged Admiral Reginald "Blinker" Hall, head of British military intelligence, to let him recruit Bell as an information-gatherer and analyst for his group in Cairo, later renamed the Arab Bureau. It was headed by Gilbert Clayton, a military officer. She left Southampton for duty there in November 1915. When she arrived, she was met by Hogarth and Lawrence.

The Cairo unit also had political operations roles. Started a year earlier, it also included an Oxford archeologist, Leonard Woolley, who had responsibility for propaganda. Wyndham Deede and Philip Graves were experts on the Turks. George Lloyd, who had introduced Bell to her most loyal guide and servant, the Armenian, Fattuh, was the financial specialist. Mark Sykes had a general fact-finding mission for the War Office.

David Lockhart "Lock" Lorimer was Political Representative in Cairo. [16] He said of Bell, with respect to the Middle East, he had "never known anyone more in the confidence of nations" than Bell.[17] While Bell had autonomy, other women such as Emily Overend Lorimer, who had taught at Oxford, were influential through their husbands. [18]

Her first assignment was as an intelligence analyst. She wrote to her mother,

For the moment I am helping Mr Hogarth to fill in the intelligence files with information as to tribes and sheikhs. It's great fun and delightful to be working with him. Our chief is Col. Clayton whom I like very much but did not know before. There are several other people in the office who are old friends; this week Mark Sykes passed through and I have seen a good deal of him. I have just heard that Neil Malcolm has arrived from Gallipoli [Gelibolu] - I think he is chief staff officer here; anyhow I have written to him and asked him to dinner if he is not too great for such invitations....Mr Hogarth and Mr Lawrence (you don't know him, he is also of Carchemish, exceedingly intelligent) met me and brought me to this hotel where they are both staying. Mrs Hall had taken me a room. And whom do you thing was the first person I met here? Cis Lascelles! her brother with whom she was staying has gone to the wars and she is going away today, to Italy I think. Mr Hogarth, Mr Lawrence and I all dine and lunch together...It's extraordinarily interesting here but I can't write about it...There are several other people in the office who are old friends; this week Mark Sykes passed through and I have seen a good deal of him. [19]

Wallach said she soon had her own office and took over the tribal political analysis, while Lawrence focused on tactical matters.[20] In his words,

The work is very interesting: mostly writing notes on railways, and troop-movements, and the nature of the country everywhere, and the climate, and the number of horses or camels or sheep or fleas in it... and then drawing maps showing all these things.[21]

Search for new governance

She recognized that the dominant dynasties were to be the House of Saud (i.e., Wahabbis) of Ibn Saud and the Hashemites of Faisal.[22] The two forces had different backers in the British government. Bell first met Abdul Aziz ibn Saud in November 1916, when he came to Basra by Percy Cox and the British Indian government. Cox and his faction had hoped he might start the revolt, but London and Cairo had backed the Hashemite Sharif or Mecca. Ibn Saud and Cox, however, had signed a treaty that was intended to prevent the Saudis from attacking the Hashemites. [23]

Ibn Saud and Bell were impressed with one another, although from totally different cultures. Wallach suggests he was "dismayed" by "this unveiled female was not only allowed in his sight but accorded priorities and permitted to engage in all the procedures, whether they were discussions on Arabian politics or social functions in his honor." She characterized him in a manner consistent with later Arab political leaders.

Politician, ruler and raider, Ibn Sa'ud illustrates a historic type. Such men as he are the exception in any community, but they are thrown up persistently by the Arab race in its own sphere, and in that sphere they meet its needs...The ultimate source of power, here as in the whole course of Arab history, is the personality of the commander. Through him, whether he be an Abbasid Khalif or an Amir of Nejd, the political entity holds, and with his disappearance it breaks.[24]

Replacing the Ottomans

By 1918, Britain was searching for a king or other acceptable ruler of the area that was to become Iraq. Russian revolutionaries had stirred the situation by releasing the Sykes-Picot Agreeement. [22]

Iraq

References

- ↑ Janet Wallach (1999), Desert Queen, Anchor Books, Random House, ISBN 1400096197, p. xxi

- ↑ Georgina Howell (2006), Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978037416120, p. 125

- ↑ Howell, p. 3

- ↑ Barbara Furst (2005), "Deja vu all over again, Gertrude Bell and modern Iraq, the extraordinary Englishwoman who played a key role in the formation of modern Iraq confronted many of the same problems the U.S. and Iraq face today", AmericanDiplomacy.org

- ↑ Elizabeth Burgoyne (1958), Gertrude Bell: From her personal papers, 1889-1914, Ernest Benn, pp. 15-16

- ↑ H.V.F. Winstone (1978), Gertrude Bell, Quartet Books, ISBN 070422203x, pp. 10-12}}

- ↑ Winstone, p. 13

- ↑ Wallach, pp. 24-25

- ↑ Lady Bell, D.B.E., ed. (1927), The Letters of Gertrude Bell, vol. 1, Boni and LiverightLetter to Horace Marshall, Gulahek, June 18, 1892

- ↑ Burgoyne, pp. 28-29

- ↑ Wallach, pp. 33-37

- ↑ Wallach, pp. 51-54

- ↑ Winstone, p. 80

- ↑ Wallach, pp. 77-78

- ↑ Winstone, pp. 107-109

- ↑ Penelope Tuson (2003), Playing the game: the story of Western women in Arabia, I.B. Tauris, p. 2

- ↑ Wallach, p. 141

- ↑ Mélanie Torrent, "Book review: Playing the Game: Western Women in Arabia (by Penelope Tuson, I.B. Tauris, 2003)", Cercles

- ↑ Gertrude Bell (30 November 1915), Letters 30/11/1915, Gertrude Bell Archives, University of Newcastle

- ↑ Wallach, p. 149

- ↑ T. E. Lawrence (18 November 1916), "T.E. Lawrence to his family", T.E. Lawrence Studies

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Christopher Hitchens (June 2007), "The Woman Who Made Iraq", The Atlantic

- ↑ Wallach, pp. 186-188

- ↑ Communique for the Foreign Office, cited by Wallach, p. 187

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- CZ Live

- History Workgroup

- Archaeology Workgroup

- Politics Workgroup

- International relations Subgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- History Content

- Archaeology Content

- Politics Content

- History tag

- Archaeology tag

- International relations tag