Iraq War

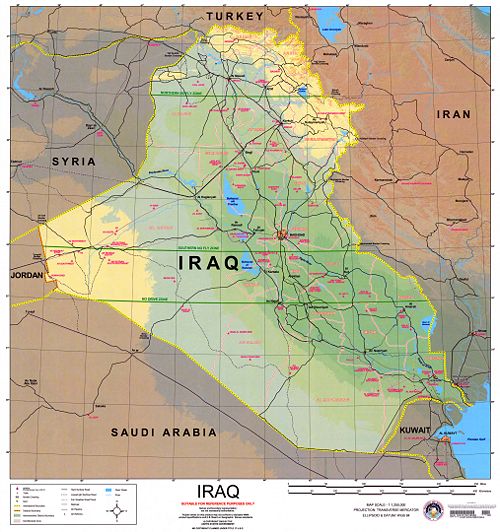

The Iraq War was the invasion of Iraq in 2003 by a multinational coalition led by the United States of America. Military operations were conducted by forces from the U.S., the United Kingdom, Australia and Poland, and was supported in various ways by many other countries, some of which allowed attacks to be launched or controlled from their territory. The U.N. neither approved nor censured the war, which was never a formally declared war. The U.S. refers to it as Operation IRAQI FREEDOM. Continuing operations are under the command of Multi-National Force-Iraq.

This war is to be distinguished from the Gulf War of 1991, following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990. The Gulf War had United Nations authorization. Further, both these wars should be differentiated from the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988.

The war had quick result of the removal (and later execution) of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and the formation of a democratically elected parliament and ratified constitution, which won UN approval. However, an amorphous insurgency since then has produced large numbers of civilian deaths and an unstable Iraqi government. It has generated enormous political controversy in the U.S. and other countries.

The main rationale for the invasion was Iraq’s continued violation of the 1991 agreement (in particular United Nations Resolution 687) that the country allow UN weapons inspectors unhindered access to nuclear facilities, as well as the country’s failure to observe several UN resolutions ordering Iraq to comply with Resolution 687. The US government cited intelligence reports that Iraq was actively supporting terrorists and developing weapons of mass destruction (WMD) as additional and acute reasons to invade. Though there was some justification before October 2002 for believing this intelligence credible, a later Senate investigation found that the intelligence was inaccurate and that the intelligence community failed to communicate this properly to the Bush administration[1].

Factors Leading Up to the Invasion

There were a wide range of opinions that Saddam Hussein's Iraq had a negative effect on regional and world stability, although many of the opinionmakers intensely disagreed on the ways in which it was destabilizing. This idea certainly did not begin with 9/11.

Iraq had had and used chemical weapons in the Iran-Iraq War and had active missile, biological weapon and nuclear weapon development programs. These provided Saddam with both a means of threatening and deterring within the region.

He also supported regional terrorists, but there is now little evidence he had operational control of terrorists acting outside the region. Saddam had attempted an assassination of former President George H. W. Bush.

The issue of non-national terrorism, however, took on new intensity after the 9-11 attack.

The Authorization for the Use of Military Force that gave the George W. Bush Administration its legal authority to attack Iraq did not specifically depend on a proven relationship between Iraq and 9-11, or a specific WMD threat to the United States. Both, however, were assumed.

Clinton Administration

After the Gulf War in 1991, United Nations Resolution 687 specified that Iraq must destroy all weapons of mass destruction (WMD). A large amount of WMDs were indeed destroyed under UN supervision (UNSCOM). Two no-fly zones were also instituted in northern and southern Iraq where Iraqi military aircraft were prohibited from flying. The United States and the United Kingdom (and France until 1998) patrolled these zones in, respectively, Operation NORTHERN WATCH and Operation SOUTHERN WATCH.

According to Richard Clarke, the U.S. found a press report, in April 1993, of an attempt, by the Iraqi intelligence service, to assassinate former President George H. W. Bush while he was visiting Kuwait.[2] After confirmation by the CIA and FBI, a retaliatory missile strike was delivered in June of that year.[3] Searches of the records of the Iraqi service after 2003 did not provide hard evidence of such a plot, but reporter Michael Isikoff, often skeptical about U.S claims about Iraq, agreed the records might have been destroyed. [4]

The 1996 Khobar Towers bombing attacked forces, in Saudi Arabia, conducting SOUTHERN WATCH. This attack, however, appears to have been sponsored by Iran.

However, by late 1997, the the Clinton administration became dissatisfied with Iraq’s increased unwillingness to cooperate with UNSCOM inspectors. As a result of widespread expectations that the Clinton administration would decide to act with military force, the UN weapons inspectors were evacuated from the country. Iraq and the United Nations agreed to resume weapons inspections, but Saddam Hussein continued to obstruct UNSCOM teams throughout the remainder of 1998.

Congress passed the Iraq Liberation Act in October 1998:

It should be the policy of the United States to support efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq and to promote the emergence of a democratic government to replace that regime. [5]

In December 1998, President Clinton authorized military action against Iraq. Between December 16 and 19, 1998, US and UK missiles and aircraft attcked military and government targets in Iraq in Operation DESERT FOX. It was widely understood that the Clinton administration intended Operation Desert Fox to be not merely a campaign of punishment for Iraq’s failure to cooperate but also to weaken the regime in advance of orchestrated efforts to cause regime change. In that respect, Clinton administration policy was ineffective.

As a result of Iraq’s barring inspectors from the country, UNSCOM inspections of Iraq’s WMD effectively came to an end and in March 1999, the UN concluded that the UNSCOM mandate should end. In December 1999, the UN passed UN Security Council Resolution 1284, setting up UNMOVIC (United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission), headed by Swedish diplomat Hans Blix, which was to identify the remaining WMD arsenals in Iraq. Because UNMOVIC was banned from Iraq, the world had to rely on indirect evidence, most of which turned out to be false or inaccurate.[6] Iraq policy during the remainder of the Clinton presidency was marked by a return to the containment regime that existed before Operation Desert Fox, but now without the benefit of direct intelligence.

Bush Administration Policy

Policy before 9/11 Attacks

In the early days of the Bush administration, President George W. Bush expressed dissatisfaction with his predecessor’s foreign policy, in particular with regard to Iraq, which he considered weak and half-hearted. When Bush and Clinton met in the days of transition, on December 19, 2000, Clinton said that his understanding of Bush's priorities, from reading his campaign statements, were national missile defense and Iraq. Bush said that was correct. Clinton suggested Bush consider other priorities, including al-Qaeda, Middle East diplomacy, North Korea, the nuclear competition between India and Pakistan, and, only then, Iraq. Bush did not respond. [7]

During the campaign, Bush had criticized President Clinton as too widely engaged in too many conflicts, acting as the “world’s policeman.” In the end, President Bush believed Clinton had lacked the necessary resolve to hold Saddam Hussein accountable for his failure to comply with UN resolutions. Bush also questioned America’s membership in NATO and involvement in UN diplomacy, which led some to believe he was moving towards a more isolationist view of foreign policy.[8]

At the same time, Bush continued to favor executing the policy President Clinton had approved but not acted on: to actively proceed to effect regime change in Iraq. In January 2002, Time Magazine reported that since President Bush took office he had been grumbling about finishing the job his father started. [9]

On February 16, 2001 a number of US and UK warplanes attacked Baghdad, nearly two years before the start of the Iraq war. [10].

Iraqi WMD and the War on Terror

The attacks of September 11, 2001 shaped the policies of the Bush administration towards Iraq. President Bush saw them as confirmation of his beliefs that the international community’s failure to enforce compliance with UN resolution and America’s irresolute foreign policy had emboldened rogue states and international terrorist groups. Because Iraq was known to have had and used WMD in the past and because Iraq had blocked UN supervision of the destruction of its WMD, there remained great uncertainty about Iraq’s WMD arsenal. The Bush administration made Iraq of central importance to its national security policy. Combined with his isolationist foreign policy beliefs, President Bush started to formulate what has become known as the Bush Doctrine. The doctrine is most fully expressed in the administration’s National Security Strategy of the United States of America, published in September 2002. In it, the President states:

We will disrupt and destroy terrorist organizations by (…) direct and continuous action using all the elements of national and international power. Our immediate focus will be those terrorist organizations of global reach and any terrorist or state sponsor of terrorism which attempts to gain or use weapons of mass destruction (WMD) or their precursors.[11]

The administration included Iraq in a series of states it considered acutely dangerous to world peace. In his 2002 State of the Union President Bush called Iraq part of an “axis of evil” together with Iran and North Korea.[12] In this address the president also claimed the right to wage a preventive war, as distinct from a preemptive attack. Early in 2002, the administration began pressuring Iraq as well as the international community on greater compliance by Iraq with UN resolutions.

Not all the senior officials of the administration treated attacking Iraq as a high priority. Some believed there was no case, while others felt that Afghanistan needed a higher priority. While Colin Powell eventually argued for Iraqi WMD before the United Nations, he and his deputy, Richard Armitage, internally raised questions. Senators Joe Biden, Richard Lugar, and Chuck Hagel were drafting legislation to limit Bush's authority; Biden said he was getting support from Powell and Armitage. [13]

Strategic planning

Not all the planning dates may seem in proper sequence; this is not anything suspicious as some of the work was already in progress as part of routine staff activity, while other work was started by informal communications.

Even before the 9-11 attacks, regime change in Saddam Hussein's Iraq was a high priority of the George W. Bush Administration. According to This is not to suggest that previous Administrations had not been considering it, and had been steadily carrying out air attacks in support of the no-fly zones (Operation SOUTHERN WATCH and Operation NORTHERN WATCH), as well as air strikes (Operation DESERT FOX). Nevertheless, the priorities changed.

Another change, in the Bush Administration, was an emphasis on military transformation, or using different approaches than "fighting the last war". Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was a constant advocate of transformation, emphasizing higher technology, more flexibility, and smaller forces, rather than the large heavy forces that were optimized to fight the Soviet Union. This was especially true after early operations in the Afghanistan War (2001-), where large U.S. ground forces were not used, but instead extensive special operations working with Afghan forces and using air power. Every war is different, however, and the reality in Afghanistan is there was an existing civil war and substantial indigenous resistance forces.

Assumed links between 9/11 and Iraq

Late in the evening of 9/11, the President had been told, by CIA chief George Tenet, that there was strong linkage to al-Qaeda. [14] On September 12, President Bush directed counterterrorism adviser Richard Clarke to review all information and reconsider if Saddam was involved in 9/11.[15]

Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz sent Rumsfeld a memo, on September 17, called "Preventing More Events"; it argued that there was a better than 1 in 10 chance that Saddam was behind 9/11. [16] He had been told, by the CIA and FBI, that there was clear linkage to al-Qaeda, but said the CIA lacked imagination.[17] On September 19, 2001, the advisory Defense Advisory Board, chaired by Richard Perle, met for two days. Iraq was the focus. Among the speakers was Ahmed Chalabi, a controversial Iraqi exile who argued for an approach similar to the not-yet-executed approach to Afghanistan: U.S. air and other support to insurgent Iraqis. [18]

On the same day, Bush had told Tenet that he wanted links between Iraq and 9/11 explored. [19]

While Tenet agreed there was a connection between al-Qaeda and 9-11, and that Saddam was supporting Palestinian and European terrorists, he said that the CIA could not make a firm connection between al-Qaeda and Iraq. While CIA continued its analysis, it accepted a briefing from a Pentagon group, under Douglas Feith, to share its ideas about an Iran-9/11 connection. This was presented at CIA headquarters on August 14, 2002. According to Tenet, while Feith's team felt they had found things, in raw reports, that CIA had missed, they were not using the skills of professional intelligence analysts to consider other than the desired conclusion. His attention immediately was caught by a naval reservist working for Feith, Tina Shelton, who said the relationship between al-Qaeda and Iraq was an "open and shut case...no further analysis is required." A slide said there was a "mature, symbiotic relationship", which Tenet did not believe was supported. Pre-9/11 coordination between al-Qaeda operative Mohammed Atta, in Prague, with the Iraqi intelligence service had become likely; Tenet described this association, which was later disproved, He called aside VADM Jake Jacoby, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, and telling him he worked for Rumsfeld and Tenet, and was to remove himself from Feith's policy channels. Later, Tenet learned that the Feith team was presenting to the White House, NSC, and Office of the Vice President. [20]

It appeared a matter of faith in the White House, especially with Cheney, that a link existed between al-Qaeda and 9/11, and Iraq War policy assumed it. A February 2007 report by the Department of Defense Inspector General said no laws were broken, but Feith's group bypassed Intelligence Community safeguards [21] On June 1, 2009, Cheney agreed that the evidence shows no direct link, but the invasion was still warranted due to Saddam's general support of terror.[22]

Reviews by Rumsfeld

CENTCOM had a contingency plan for a new war with Iraq, designated OPLAN 1003-98. It assumed Iraq would launch an attack as it had done in 1990. Rumsfeld had OPLAN 1003-98 presented by LTG Greg Newbold, director of operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in late 2001. Rumsfeld believed the plan, which called for up to 500,000 troops, was far too large; Rumsfeld thought that no more than 125,000 would be needed. Newbold later said he regretted he did not say, at the time,

Mr. Secretary, if you try to put a number on a mission like this, you may cause enormous mistakes. Give the military the task, give the military what you would like to see them do, and let them come up with it. I was the junior military man in the room, but I regret not saying it[23]

Informally, Franks had called it "DESERT STORM II", using three corps as in 1991, but to force collapse of Saddam Hussein's regime. On November 27, he told the Secretary of Defense that he had a new concept, but that detailed planning would be needed. [24] Franks told Rumsfeld, during a videoconference on December 4, 2001, that it was a stale, troop-heavy concept. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) Dick Myers, Vice CJCS Peter Pace, and Undersecretary of Defense Douglas Feith were on the Washington end. Franks intended to ignore Feith, who he described as a "master of the off-the-wall question that rarely had relevance to operational problems." [25]

Franks proposed three basic options:

- ROBUST OPTION: Every country in the region providing support; operations from Turkey in the north, Jordan and Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in the south, air and naval bases in the Gulf states, with support bases in Egypt, Central Asia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria. This would allow near-simultaneous ground and air operations.

- REDUCED OPTION: A lesser number of countries supporting would mean a sequential air and ground operation.

- UNILATERAL OPTION: If launching forces from Kuwait, U.S. ships, and U.S. aircraft from distant bases, the air and ground operations would be "absolutely sequential" due to the lack of infrastructure to bring in all ground forces at once.

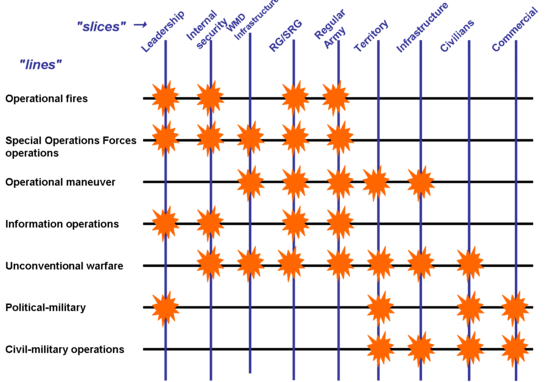

Franks wrote that during the Afghanistan planning, he had developed a technique that presented, visiually, the tasks to be done ("lines of operation") and the country or resource that would be affected by these tasks ("slices"). It is not clear when he first drew this visual aid for Iraq, although it was part of the December 12 briefing to Rumsfeld; the version reproduced in his book was dated December 8.

In this model, operational fires are strikes by aircraft, artillery, and missiles. Special Operations Forces operations are principally special reconnaissance and direct action (military); unconventional warfare involves both military and CIA guerillas. Information operations, as a line, includes psychological operations, electronic warfare, deception, and computer network operations; politicomilitary and civil-military operations are doctrinally part of information operations but are shown separately here. RG and SRG are, respectively, the Iraqi Republican Guard and Special Republican Guard elite combat formations.

Rumsfeld liked the presentation. He asked Franks what came next, and Franks said improving the forces in the region. Rumsfeld cautioned him that the President had not made the go-to-war decision, and Franks clarified that he referred to preparation:

- Triple the size of the ground forces now in Kuwait

- Increase the number of carrier strike groups in the area

- Improve infrastructure

- Discuss contingency requirements with allies

Franks said the activities could look like routine training. He pointed out that an additional 100,000 troops and 250 aircraft would not fit into Kuwait, and more basing would be needed. Rumsfeld urged that it would have to be done faster "more quickly than the military usually works". The next step was a face-to-face briefing on December 27. [26]

Rumsfeld calls for new planning

Early warning of Rumsfeld's desires came to LTC Thomas Reilly, chief of planning for Third United States Army, still based at Fort McPherson in the U.S. While Third Army would become the Coalition Forces Land Component of CENTCOM, it had not yet been so designated, whenn Reilly received the notice on September 13, 2001. It used the term POLO STEP, the code word for Franks' concept of operations. [27]

On October 9, 2002, GEN Eric Shinseki, Chief of Staff of the Army, told staff officers "From today forward the main effort of the US Army must be to prepare for war with Iraq". [28]

Special operations

George Tenet, Director of Central Intelligence, had a major role in the decision to go to war, but also how it was to be fought. In the mid-nineties, CIA had found that a first coup attempt simply had gotten Iraqi CIA assets killed. The lesson learned from Afghanistan was that "covert action, effectively coupled with a larger military plan, could succeed. What we were telling the vice president that day [in early 2002] was that CIA could not go it alone in toppling Saddam...in Iraq, unlike in Afghanistan, CIA's role was to provide information to the military...assess the political environment...coordinate the efforts of indigenous networks of supporters for U.S. military advances..." In February 2002, the Agency re-created the Northern Iraq Liaison Element (NILE) teams to work with the Kurds. Later, CIA officers worked to encourage surrender, but this soon proved impractical; the U.S. forces were so small that the prisoners would have outnumbered the invaders. [29]

Theater/operational planning

In the Gulf War, there was no common commander for all land forces; GEN H Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. gave direct orders to the U.S. Army and Marine unites. Experience both then and in WWII showed the need for a land forces commander.

In November 2001, the commander of United States Central Command, Tommy Franks[30] designated Third United States Army as the CENTCOM Land Forces Component Command (CFLCC). LTG David McKiernan took command of Third Army in September 2002. According to MG Henry "Hank" Stratman, deputy commanding general for support of Third Army, eventual combat with Iraq was assumed when he took his post in the summer of 2001, even before the 9-11 attack.

With the recommendation of Newt Gingrich, COL Doug Macgregor prepared a briefing, which went to Runsfeld, which went against the conventional wisdom that large forces would be needed to defeat Saddam. [31] Macgregor geve the briefing to Gingrich on December 31, 2001. It advocated a quick strike into Baghdad by three brigade-sized forces, followed by 15,000 light infantry forces to maintain order.

Macgregor was sent to brief GEN Tommy Franks, commanding U.S. Central Command, on January 12, 2002. After Macgregor briefed Franks, Franks responded, "Attack from a cold start. I agree. Straight at Baghdad. Small and fast. I agree. Simultaneous air and ground. Probably, but not sure yet." After his return to Washington, Macgregor decided that Franks had given him a polite reception as a courtesy to Rumsfeld; Macgregor wrote a memo of the meeting, which Gingrich forwarded to Dick Cheney and other political contacts. Franks' planner, MG Gene Renuart, argued to Rumsfeld that Macgregor's plan was too light.

Detailed planning by CENTCOM began while active combat was ongoing in Afghanistan, in December 2002.[32] At the time, GEN Eric Shinseki, then Chief of Staff of the Army, testified to Congress that the number of troops approved by Rumsfeld was inadequate. Shinseki, however, was not in the chain of command for operational deployment. Although the Chief of Staff is the senior officer of the United States Army, he is responsible for developing doctrine and preparing forces for use by the combatant commanders.

GEN Franks briefed Secretary Rumsfeld on February 1, with two alternative plans. The first, informally called "DESERT STORM II", repeated the sequential approach of Operation DESERT STORM:[33]

- Phase I: buildup of forces before invasion, with increased air strikes in the no-fly zones and early staging of special operations forces; prestaging of approximately 160,000 troops

- Phase II: Air-centric operations of approximately 3 weeks, preparing the battlefield for the major ground forces attacks

- Phase III: Major ground forces attack with approximately 105,000 troops

- Phase IV: Occupation and reconstruction

The alternative, preferred by Franks, was called RUNNING START, and was chosen as the next planning point. It moved Special Operations preparation into Phase I, made the air and ground phases essentially simultaneous (i.e., merged into a combined Phase III of decisive combat operations), and then a reconstruction phase; the phases were not renumbered.

In the next review, additional alternatives were introduced, still assuming some level of simultaneous air and ground attack, as distinct from the separate air phase of Operation DESERT STORM. They varied with the number of troops required:

- GENERATED START took the most troops, and was considered impractical almost from the beginning; Saddam had learned not to give the U.S. time to prepare. GENERATED START assumed the U.S. would launch an attack only when it had all forces in theater, which would take the longest time and be inflexible.

- RUNNING START option, which assumed launching combat operations with minimum forces and continuing to deploy forces and employ them as they arrived. The final option stemmed from wargaming the running start.

- HYBRID PLAN, which evolved from war-gaming RUNNING START. reflected an assessment that the minimum force required reached a higher number of troops than envisioned in the running start option.

The selected plan was a compromise solution between HYBRID and RUNNING SSTART, with more forces than the latter but fewer than the former. RUNNING START offered operational surprise and less demand for synchronization than HYBRID PLAN.

Critical factors

Several key factors had the potential to override any plan. First, the Iraqi oil infrastructure had to be protected from sabotage, as its revenue would be key in reconstruction. The military and CIA had different information as to Saddam's intentions; as a practical matter, the oil facilities were kept under close surveillance as the attack grew closer. [34]

Second, Saddam Hussein was the key to Iraqi resistance. Ideally, he would leave the country. If, however, he could be located and killed by air attack, that also would change priorities.

V Corps

While V Corps was stationed in Germany, all plans assumed it would be the heavy striking force in any attack against southern Iraq. Planning for such an attack had long been one of its responsibilities. Planning intensity intensified in April 2002. It deployed to Poland and conducted Exercise VICTORY STRIKE, a training exercise with Iraq in mind. Under CFLCC, a command exercise, LUCKY WARRIOR, in Kuwait, involved V Corps and I MEF. Next, the annual CENTCOM exercise, INTERNAL LOOK, added practice for the Joint Force Air Component Command (JFACC), while Special Operations Command for CENTCOM (SOCCENT) formally established two Joint Special Operations Task Forces (JSOTF): JSOTF-North and JSOTF-West. It assumed I MEF with part of its air wing, 1st Marine Division with two regimental combat teams, and V Corps with all of 3rd ID, an attack helicopter regiment, and part of the corps artillery. [28]

I MEF

U.S. Marine planning had, since the Second World War, focused on relatively small, quick-response operations from the sea, typically by brigade-sized Marine Expeditionary Units. They had fought a large-scale operation in Operation DESERT SABER.

Nevertheless, the first Operational Planning Team, held in March 2002, assumed that the I MEF effort would support large-scale Army movement. Its concept was that the Marines would send "Task Force South" to move from Kuwait, capture Jalibah Airport, and stage from there to capture Qalat Sikar and An Kut airfields closer to Baghdad. They would then secure southern Iraq, while the Army brought in resources for the main attack.

This was too deliberate and logistics-intense for Rumsfeld's "RUNNING START" model. Counterproposals were sent back to plan for single Army and Marine brigades to start individual advances. I MEF countered that it was a better overall headquarters than V Corps, since it was experienced in controlling air operations where an Army corps was not. In the planning of July 2002, it was tentatively accepted that I MEF might indeed be the main headquarters. The U.S. Marines also welcomed the participation of British Royal Marines.[35]

The Marines also needed to coordinate with Special Operations forces.

Special Operations forces

Special Operations had played a major and effective part in Afghanistan, and were visible to Rumsfeld and Franks. As in Afghanistan, they divided into "white" (i.e., acknowledged) and "black" (i.e., covert forces).

The main white operations were 5th Special Forces Group in the south, under COL John Mulholland, and 10th Special Forces Group in the north under COL Michael Repass. They reported both to CENTCOM and Task Force 20.

Larger, however, was Task Force 20, secretly located on Saudi soil at Ar'ar, commanded by MG Dell Dailey, who was also the overall head of Joint Special Operations Command. TF 20 included Delta Force, the 75th Ranger Regiment, MC-130 COMBAT TALON and other large Air Force Special Operations Command aircraft and helicopters from the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment. In an unprecedented move, the task force had been supplemented with a conventional paratroop battalion from the 82nd Airborne Division. [36]

One of the key, although controversial, contingency missions for TF 20 was seizure of Baghdad International Airport, especially if the Saddam Hussein regime collapsed. The latter was always at the minds of the senior civilian leaders, but contingency planning for leadership collapse went back to the Second World War: Operation RANKIN CASE C. In WWII, that indeed was an airborne mission. In this war, however, the 3rd Infantry Division staff felt they could do the job more efficiently and with less risk.

Delta and supporting TF20 units, however, had other missions.

The Turkish front

Relations among Turkey, the Iraqi government, the Kurds of Iraq, separatist Kurds in Turkey, and, to a lesser extent, Kurds in neighboring countries has always been sensitive.

Using the 4th Infantry Division (4ID), the most technically advanced in the U.S. Army, planners wanted to launch a northern front from Turkey, but Turkish public opinion was opposed. On March 1, the Turkish Parliament refused to consent to any U.S. operations, including overflights by cruise missiles or aircraft, search and rescue, much less ground troops. At this point, the 4th Infantry Division (U.S.) was already in ships off the Turkish coast. Colin Powell had considered the need for a northern front overrated. If there were no northern front and Iraqi forces moved south, that would simply make them better targets. He did think Rumsfeld liked the idea as part of keeping the southern force smaller.

Eventually, Turkey gave some limited and low-visibility access, including overflights by aircraft and missiles, and operations by the 10th Special Forces Group, under COL Charlie Cleveland. On March 22, it flew to the Bashur and Sulaymaniyah areas in the Turkish zones of northern Iraq, using a circuitous, low-altitude, and dangerous path over the Sinai Peninsula, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia. Turkey did allow one damaged MC-130 COMBAT TALON to make an emergency landing in Turkey. The 10th Group eventually raised 70,000 Kurdish fighters that interfered with the southern movement of Iraqi Army units. [37]

McKiernan, in February, had recommended to Franks essentially the same thing as did Powell: send the 4th ID to the south. If the Turks changed their position, units could always be sent there. [38] Franks, however, thought that keeping a northern threat would keep the Iraqis distracted. He believed that the Iraqis focused on the 4th ID as the main invasion force; even when its ships moved south through the Suez Canal, Arab media reports assumed that it would land in Jordan and attack from the west. By not committing the division to the south, he believed he could maintain a diversion. [39]

Phase IV Planning

During the planning phase, Rumsfeld told Franks that LTG Jay Garner would be responsible for reconstruction, reporting to CENTCOM. [40] A number of retired generals have been highly critical of the plan, focused especially on what they considered the unrealistic goals of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. They include Paul Eaton, who headed training of the Iraqi military in 2003-2004; formal chiefs of United States Central Command (Anthony Zinni and Joseph Hoar); Greg Newbold, Director of the Joint staff from 2000 to 2002; John Riggs, a planner who had criticized personnel levels, in public, while on duty; division commanders Charles Swannack and John Baptiste.[41]

Major combat phase

As with any war, no plan survives contact with the enemy. Both sides did consider Baghdad the key center of gravity, but both made incorrect assumptions about the enemy's plans. The U.S. was still sensitive over the casualties taken by a too-light raid in Operation GOTHIC SERPENT in Mogadishu, Somalia. As a result, the initial concept of operations was to surround Baghdad with tanks, while airborne and air assault infantry cleared it block-by-block. [42]

The U.S. also expected the more determined Iraqi forces, such as the Special Republican Guard and the Saddam Fedayeen, to stay in the cities and fight from cover. Before the invasion, the Fedayeen were seen as Uday Hussein's personal paramilitary force, founded in the mid-1990s. They had become known in 2000 and 2001, beheading dissenting women in the streets claiming they were prostitutes. "It was a very new phenomenon, the first time women in Iraq have been beheaded in public," Muhannad Eshaiker of the California-based Iraqi Forum for Democracy told ABC. [43] They had not been expected to be a force in battle. It was clear that the fedayeen had minimal military training. They seemed unaware of the lethality of the U.S. armored vehicles, and aggressively but haphazardly attacked them. [44] Senior Iraqi Army officers seemed to believe their own propaganda and assume that the war would go well, and there would never be tanks in Baghdad. It was only Special Republican Guard, Saddam Fedayeen, and unexpected Syrian mercenaries that seemed to understand the reality.[45] In an interview after the end of high-intensity combat, MG Buford Blount, commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, said "...there were many, I think, Syrian and other countries that had sent personnel; the countries didn't, I think individuals came over on their own that were recruited and paid for by the Ba'ath Party to come over and fight the Americans. We dealt with those individuals there for a two- or three-day period, had a lot of contact with them, but have not seen a reoccurrence of that at this point."[46]

There was great U.S. concern that the Iraqis would use chemical weapons once their forces passed some "red line" on the approach to Baghdad. Franks had a communications intercept that translated "Blood. Blood. Blood." This, along with the discovery of chemical protective equipment, put him on edge.

The chemical warfare did not materialize, but an unexpected surprise was that the Fedayeen and mercenaries jeopardized the supply lines to the advancing spearheads. To make matters worse, these irregular forces attacked with civilian vehicles, in civilian clothes, and from civilian sites. This unquestionably led to civilian casualties. It also forced the U.S. to assign forces that had been planned to hold ground or take cities, such as the 82nd Airborne Division and 101st Airborne Division, to shift some of their effort to road security.

Major units

Ground combat began with two corps formations, the Army's V Corps under LTG William "Scott" Wallace and the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force (including British units) under LTG James Conway. At the start, the V Corps was primarily the 3rd Infantry Division with supporting forces, but was steadily reinforced with additional divisions, such as the 82nd and 101st. The 4th ID did not deploy until large-scale combat was almost over.

The regular ground forces were under Coalition Land Forces Component commander LTG David McKiernan. Substantial special operations forces, both overt and covert, operated in coordination, but under a different component commander.

Moves of opportunity

The "RUNNING START" began with near-simultaneous air and ground attacks. The original plan had been to conduct limited air strikes against border operation posts on March 19, along with infiltration, under air cover, of Special Operations Forces from the military and CIA, the latter designated the Southern Iraq Liaison Element. Full-strength bombing was to begin on March 21.

When communications intelligence on March 19 indicated that Saddam might be at a location called Dora Farms, a contingency air operation went began on the 20th.[47] Times were tight; the ultimatum to Saddam expired at 4 AM local time; the F-117 aircraft had to be out of the area before dawn at approxiately 5:30. They took off at 3:30.[48] Cruise missile hit aboveground targets at Dora Farms five minutes after the F-117's had dropped ground-penetrating bombs. Saddam, however, was not at the site.

Special operations forces were already operating in Iraq. Special operations forces (SOF) also moved into action, seizing oil and gas platforms in the south. SOF in the west positioned themselves to strike at airfields, missile sites, and suspected WMD facilities. In the north, they worked with the Kurdish resistance to pin the Iraqi forces in that area.

Iraq countered with surface-to-surface missiles fired at U.S. headquarters on the afternoon of the 20th. They were shot down. [49]

Special operations probes

On the 19th, a Delta Force squadron scouted several potential WMD sites, and found no threat. [50]

Shaping the battlefield

The main operation of the "shaping the battlefield" phase began with breaking through a 10km wide Iraqi defensive line, on March 20. This phase lasted until March 23.

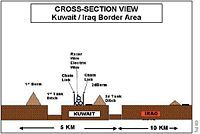

The major units positioned themselves for penetrating the Iraqi border. This was called crossing the "berm", although the berms (plural) were earthen walls that made up part of the physical barriers at the border. Note that a substantial amount of the barrier was in Kuwait. According to the U.S. Army history, much of the actual breaching was done by Kuwaitis contractors, who considered it an honor, but could also disguise some of the preparation as routine maintenance. [51] Another account, however, said that the Kuwaitis were reluctant to plow over the defenses they had built, including an electrified fence; they arranged, in discussions with McKiernan's staff, to have contrators take down sections of their barriers.[52]

Breaching the berms proper was separate from creating lanes through the defensive line, which was done by combined arms units, such as TF3-15, based on two mechanized infantry companies (Alpha and Bravo, 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry), one attached tank company (Bravo Company, 4-64 Armor), one engineer company (Alpha Company, 10th EN), and a psychological operations. It split into organized into two elements, one of armored fighting vehicles and one of wheeled vehicles.

The first combat by conventional forces, took at 3:57 PM local time, but south of the Iraqi border, between Iraqi vehicles and U.S. Marine Corps LAV-25 reconnaissance vehicles from the 3rd Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion. Marines began the actual attacks with artillery fire in the late afternoon, preceding the border crossing by the 1st Marine Division under I Marine Expeditionary Force under then-LTG James Conway. The Division cooperated closely with 1 Armored Division (U.K.) and the Army's 3d Infantry Division (U.S.)[53] The Army units were under V Corps.

Lane-clearing teams were ready on the 20th, waiting for movement on the 22nd. While they waited, they were in chemical protective clothing, donning masks when Iraqi surface-to-surface missiles were fired.

Lead Marine units first crossed the Kuwait-Iraq border and began an intensive attack on Safwan Hill, in Iraq just north of the border. [54]

Oil fields

The first Army unit to enter Iraq was the 3rd Squadron, 7th Cavalry Regiment, part of the 3rd Infantry division, at approximately 1 AM local time on the 20th according to CNN, although Defense Department reports suggest the movement was four hours later. [53] In either case, the attack time was accelerated due to concern over the Iraqis' damaging oil facilities.

When Marines seized the Crown Jewel pumping station in Zubayr, 10 miles southwest of Basra, they were concerned that machinery had been damaged, but the Iraqi managers said this was the normal state of the equipment; the Iraqi petroleum industry needed rehabilitation. [55]

As the Marines moved into the Rumaylah oil field, British forces took control of the Faw Peninsula oil facilities, as well as the port of Umm Qasr. U.S. Navy SEALs captured some of the offshore facilities. A U.S. Marine helicopter crashed, killing Marines from both countries. [56]

Attack on Talil Airfield and on Basra

On the 22nd, the 3rd Infantry division drove troughly 150 miles into Iraq, halfway to Baghdad, to the Tal Airfield. The 3rd Brigate attacked the airfield with the 1/30 Infantry protecting the flanks and the 1/15 attacking the Iraqi 11th Infantry division in defense. The 3rd Brigade captured the Talil airfield after its artillery began shelling Iraqi military emplacements there. While the 1-30th Infantry protected its flanks preventing intervention by forces in Nasiriyah, the 1-15th Infantry Regiment assaulted the airfield inflicting serious losses on Iraq's 11th Infantry Division, which was defending the location. The 3rd ID used a bounding overwatch, where one brigade at a time would attack, covered by another. [57] The 11th Infantry later surrendered resulting in the capture of some 300 prisoners.

In parallel, 1st Marine Division drove toward Bastra, destroying 10 dug-in T-55 tanks with hand-held and HMWWV-launched antitank missiles.

Eight miles south of Basra at a turnoff to Zubair, the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines Regiment took over an abandoned Iraqi command and control facility and used it as a field headquarters. The marines left this position later in the day as forces began heading closer to Basra.

Resistance by irregulars

On the 23rd, the advancing forces ran into unexpected resistance from Fedayeen irregulars, which did not present a threat to the armored fighting vehicles, but caused a problem for supply lines. They also faked surrenders and used human shields. [58] Part of the Army 509th Maintenance Company, having taken a wrong turn and driven into the city of An Nasiriyah, were ambushed and prisoners, including Jessica Lynch, taken. [59]

The first large thrust

After breaching the berm, it would take at least two movements to reach Baghdad; there would need to be regrouping on the 400 km drive to the north from Kuwait. The contingency of sudden collapse of the Iraqi leadership was always considered as a contingency.

The "darkest day"

Some of the hardest fighting came on the night of the 23rd and 24th. One component was an unsuccessful deep strike by AH-64 Apache helicopters at the Battle of Karbala. [60] This was a pure air attack; the 101st decided to defer its originally planned near-simultaneous attack, on the 14th Brigade of the Medina Division, until the 28th.[61]

U.S. Political factors

LTG Wallace had given an interview to U.S. newspapers on the 27th, in which he suggested the war might take longer than planned, due to the paramilitaries and the weather. [62] According to Gordon and Trainor, Rumsfeld felt this was disloyal, and raised it to Franks, who expressed to McKiernan that he was considering relieving Wallace. Franks had unfavorably compared the aggressiveness of V Corps to the Special Operations forces.[63] Rumsfeld, however, denied he had read the interview, but warned Syria and Iran to stay out of the irregular fighting. [64]

In his autobiography, Franks said he was told of the incident by his press officer, COL Jim Wilkinson, on the morning of the 27th, who said "a couple of reporters ambushed Scott Wallace when he popped in to visit General Petraeus at the command post." Franks said he described it as basically accurate from the perspective of a corps commander, but definitely pessimistic. Wilkinson described it as "A friggin' disaster, General. The takeaway is that we're bogged down and didn't plan this operation worth a damn." When Franks said this was untrue, Wilkinson said "perception is reality in the media. My phone has been ringing off the hook for the last hour. Everyone wants to interview you about Wallace's comments." Franks told Wilkinson to stay with operational truth, and he would talk to McKiernan. When Franks talked to McKiernan, the latter said he had warned Wallace, and Franks said "that's good enough for me. Scott is a hell of a commander. Tell him I love him and trust him."[65]

Haditha Dam

The Haditha Dam is a water and hydroelectric power facility 125 miles northwest of Karbala. CENTCOM determined that Iraqi destruction of the dam, could have an immediate impact on the fight by causing floods, and subsequent catastrophic effects on infrastructure when stored water would not be available during the summer. The assessment came from the Army Engineer Research and Development Center's (ERDC) TeleEngineering Operations Center in Vicksburg, Miss. [66] A decision was made to use Rangers to seize it; Rangers had been held in reserve for seizing WMD caches or Baghdad International Airport. JSOC had made seizing the airport, in the event of a regime collapse, a major priority; airport seizure is a classic Ranger mission, and was especially significant to MG Dailey, an aviator. The 3rd Infantry Division, however, was confident it could take the airport more reliably than JSOC. LTC Blaber, the Delta Force squadron commander, had been told the dam was a high priority, possibly as a WMD storage site.

Isakoff and Corn suggest that the dam mission was an ad hoc assignment to the Rangers, who did not have a clear mission. Rangers made a parachute jump and seized the H-1 airfield on March 27. A tank company was then airlifted to them, and the combined force, the first time armor had been put under special operations, seized the dam on April 1. Once they had it, however, they discovered it was poorly maintained. An engineer, with limited dam experience, was flown in two days later and helped maintain it, along with the Iraqi staff.[67]

The Pause

As opposed to the situation in the Afghanistan War (2001-), there was no meaningful Iraqi resistance that could be assisted by Special Operations forces, at least in Southern Iraq. The Kurds in the north were quite another matter.

Instead, the Iraqi irregular Fedayeen were a real threat to the rear areas of the advancing forces. By the 28th, Conway described the main Iraqi military as in a deliberate defense. complemented by the Fedayeen.[68] Wallace, McKiernan and Conway were all concerned with protecting their rear areas; McKiernan had released the the 82nd Airborne Division and to V Corps, for rear security, on the 26th. [69]McKiernan said that before moving north, he wanted the Republican Guard reduced by 50%, and the 101st Airborne Division committed to rear security. [70]

New raid on Karbala

Having learned lessons from the first deep helicopter raid on Karbala, an attack combining more types of force taken against the 14th Brigade of the Medina Division on March 28. Rather than Apaches alone, and in a single mass, the attack helicopter route was prepared. First, artillery and fixed-wing fighter-bombers hit the Iraqi forward areas. The close air support (CAS) aircraft would loiter in the area, and the helicopter force would include an airborne forward air controller (AFAC). Four minutes before the helicopters were to strike, MGM-140 ATACMS surface-to-surface missiles would strike air defenses.

The Apaches split into two battalion-sized elements. As no plan survives contact with the enemy, the element planned as the main attack force found few targets, while the feint element discovered the main enemy concentration.

Both forces flew differently than on the 23rd, based on the "lesson learned" about ground fire from civilian vehicles. In each formation, one helicopter provided security to the rear and two to the sides, while the rest looked for main targets. They destroyed five pickup trucks armed with heavy machine guns.

Airdrop on Bashur

On March 26, 2003, the 173rd Airborne Brigade made the largest combat paratroop operation since the Second World War. Landing in the Bashur Drop zone, they effectively opened a northern front, diverting Iraqi forces from the main ground assault from the south.[71]

It is not clear, however, that the Iraqis took this as more than a diversion, since they were reasonably certain that Turkey would not permit a large ground force to cross its border into Iraq. Supplying the 173rd was also a major challenge.

The 173rd did not see combat until April 10, when it moved into Kirkuk, after special operations forces had driven out the Republican Guard and Regular Army. It did play an important role in stability operations in Kirkuk and other Kurdish areas.

An Najaf

Karbala would still have to be taken on the ground, and An Najaf controls the approach to it. The city is along the Euphrates River, with several bridges across it. Highways 9 and 28 parallel the river; Highway 9 runs through An Najaf. On the 31st, as the heavy 3rd Infantry Division regrouped to hit the Republican Guard, the 101st Airborne Division prepared to contain An Najaf. Within hours of attacking, the 3rd Battalion, 1st Brigade of the division had secured the airport for humanitarian operations and military logistics. The 1st Battalion took an infantry training center.

An Najaf presented problems beyond the pure military, as it holds one of the holiest shrines in Islam, the Tomb of Ali, son-in-law of the Prophet and founder of Shi'a Islam. When forces from the 2nd Battalion, 1st Brigade of the 101st approached it, they were fired on by Iraqis inside. The battalion commander, aware of the cultural sensitivity, surrounded the shrine and used snipers against those inside, but would not send troops into it. [72]

The overall operational concept was to contain An Najaf from the southwest and northwest and isolate from the north and east. This would prevent enemy paramilitary forces from interdicting logistics operations in Objective RAMS and position the division to prevent other enemy forces from reinforcing An Najaf.

To do this, 3rd Infantry Division would capture the two bridges on the north and south sides, and then put blocking forces on the east and west. 1st Brigade Combat Team would take the northern bridge at Al Kifl. Due to a shortage of uncommitted troops, the brigade air defense battery, in M6 LINEBACKER armored fighting vehicles, a Bradley derivative, was reinforced with scouts and forward observers, and directed to rush the bridge. If they were lucky, they would take it; they were backed by a tank-infantry reaction force. It was needed.

Five Simultaneous Attacks

Shows of force

Before attempting to take and hold Baghdad, several peripheral or demonstration operations were used as much for psychological as kinetic attack.

Baghdad airport

A major objective had always been Baghdad International Airport. While the V Corps staff had thought the best approach to seizing it was by air assault by the 101st Airborne Division, while MG Dailey of JSOC saw it as a mission for his force, MG Buford C. "Buff" Blount III, commanding 3rd Infantry Division, felt confident he could take it. He directed the 1st Brigade, under COL William Grimsley, to move against it. 3-69 Armor was the lead battalion, under LTC David Perkins, covered by extremely heavy artillery fire. The artillery was thought to have broken the morale of the Special Republican Guard defenders. [73]

The first Coalition aircraft to use Baghdad International landed there on April 8. It remained a hazardous airfield, but it was usable by military pilots with appropriate tactical air traffic control.

First Thunder Run

COL David Perkins, commanding the Second Brigade, was concerned about a lack of momentum, and proposed a raid to MG Blount. [74] Blount agreed, and ordered Perkins to make a "Thunder Run" raid into the city proper on April 4. The raid used a battalion task force built around "Rogue Battalion", or the "Desert Rogues" of 1st Battalion, 64th Armored Regiment, under LTC Eric Schwartz.

It was a day that saw a surreal contrast between the announcements of the Iraqi information minister, Mohammed Saeed al-Sahaf, known as "Baghdad Bob", and the U.S. probes into Baghdad, called "Thunder Runs". Objectively, they were high-speed reconnaissance in force by U.S. armored columns, to which Franks gave that name after similar operations during the Vietnam War: "a unit of armor and mechanized infantry moving at high speed through a built-up area such as a city. The purpose was either to catch the enemy off guard or overwhelm him with force."[75] A correspondent, perhaps tastelessly but not completely inaccurately, referred to them as "the longest drive-by shooting in history". [76] As video, from an embedded reporter in the 1-64 Armor task force and from an UAV flying above, showed armored vehicles on the highway, driving up to Baghdad International Airport from a different route than that taken by 3-69 Armor, the information minister claimed

They are not near Baghdad. But if they are, we shall slaughter them

It must be understood that this was a short operation, lasting 2.5 hours, by a battalion task force. U.S. casualties were light but casualties, largely among ill-trained irregulars, were estimated as between 800 and 1000. Lessons were learned, including the capabilities and limitations of UAV and Blue Force Tracker for keeping higher headquarters informed. While they had moved down a seemingly high-speed highway, they learned overpasses were key chokepoints.[77]

Second Thunder Run

Blount, on April 5, reviewed the result of the first Thunder Run, and considered if another one would contribute to his goal of keeping pressure on the Iraqis, while major troop movements were being prepared. He expected reinforcement of Highway 8 and more digging in by the Iraqis, and thought that one, or multiple, Thunder Runs would be good preparation for the expected eventual siege of Baghdad.

Perkins, at the brigade level, actually had a more ambitious, information-centric goal than division and corps, which saw the raid as another in-and-out operations. [77]

Overall division operations had taken control of the intersection of Highways 1 and 8, which controlled access both to the airport, and to the city, 18 km north. A new run would start from there, and also use all of the Second Brigade rather than a battalion task force. [78]

The second "Thunder Run", on April 7, stopped on the Presidential Palace grounds.

Regime collapse

The Coalition had originally expected a house-by-house fight in Baghdad, and to be attacked with chemical weapons as they came close. Before the invasion, they had expected the greatest resistance to be from the Special Republican Guard, Special Security Organization, and Saddam Fedayeen. It was a surprise when the Fedayeen were among the first defenders, attacking the lines of communications.

Nevertheless, there was a disconnect between on-the-ground reality and the positions taken by Saddam's spokesman.

The main Baghdad operation, leading to regime collapse, was a completely joint effort, using ground, air, and maritime components. It began on April 7. V Corps was responsible for the main ground offensive, prepared by the "five simultaneous attacks" through the Karbala Gap. Its major elements were the heavy 3rd Infantry Division, highly mobile 101st Airborne Division, 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment and the light 82nd Airborne. The latter two were focused on securing the lines of communication and the flanks. Now in theater, the 4th Infantry Division, which was the most advanced division in the Army, reinforced V Corps. South and EastBaghdad was not the only area of concern; I MEF and the British forces secured the southern oilfields by the 10th and Saddam's home area of Tikrit by the 14th. Northern frontSpecial Operations forces secured the northern oil fields on the 10th. Ramadi surrendered on the 13th. Air operationsThe first Coalition aircraft landed at Baghdad International Airport on April 8. Securing BaghdadBaghdad was effectively in U.S. hands by April 9. Deputy CENTCOM commander Mike DeLong said three factors made looting much worse than expected:[79]

Interim Military GovernmentOn April 16, Franks declared the end of major combat,[80] and ordered the withdrawal of the major U.S. combat units. The CENTCOM forward headquarters in Qatar and I MEF were to be withdrawn. U.S. forces would be reduced to 30,000 by the end of August, which the U.S. believed was adequate. [81] While the fighting was in progress, he asked for a provisional government to be established, and LTG (ret) Jay Garner was named, and created the Office for Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance (OHRA). Garner had experience running humanitarian operations in Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War. Garner said that he always considered himself in a temporary role. He said that Franks had been promised a large number of constabulary from other nations; his immediate goal, before de-Baathification, was "...setting up to pay the civil servants and the police and the pensioners."[82] In the PBS interview, Garner's interviewer asked him if his superiors wanted him simply prepare for Chalabi, a neoconservative favorite, to take over. Garner denied this was Rumsfeld's plan, quoting him as saying "I don't have a candidate. The best man will rise." Garner did say that Chalabi "certainly he was the darling of Doug Feith and [former Defense Policy Board Chairman] Richard Perle and probably ...Paul Wolfowitz, perhaps (Vice-President) Dick Cheney. I'm not sure." He said that he was prepared to bring back the Army, "By the 15th of May, we had a large number of Iraqi army located that were ready to come back, and the Treasury guys were ready to pay them. When the order came out to disband, [it] shocked me, because I didn't know we were going to do that. All along I thought we were bringing back the Iraqi army. ... Why we didn't do that, I don't know." Garner was replaced in a month, on May 7, by L. Paul Bremer of the U.S. Department of State. [83] Bremer established the Coalition Provisional Authority, which was not well coordinated with the military. CFLCC was redesignated Combined Joint Task Force 7 (CJTF-7) on May 1, but McKiernan's headquarters was replaced by V Corps, then under LTG Wallace. MG Ricardo Sanchez, then commanding 1st Armored Division (U.S.) in Germany, was promoted to LTG and given command of V Corps. According to Sanchez, Franks had not specified a specific Phase IV role for CENTCOM or V Corps. [84] Franks and DeLong recommended that only the senior Ba'ath Party leadership be blacklisted, on the assumption, much as with the Soviet Communist Party, that Party members ran most of the basic government services. Nevertheless, the Party was dissolved on May 12, and CENTCOM was faced with the job of creating a new civilian infrastructure. Garner said that he had protested full de-Baathication to Bremer, who said "These are the directions I have. I have directions to execute this..." [82] Insurgency, Counterinsurgency, or Occupation, depending on perspectiveThe headquarters for foreign military units in Iraq is Multi-national Force-Iraq (MNF-I). On an overall basis, it reports to the United States Central Command, which also commands the U.S. troops in MNF-I. Other units report to their home nations, although there are a number of non-US commanders from the MNF-I Deputy Commanding General, and Australian, British and Polish commanders at division level. References

|