Cruiser

A cruiser is a warship of significant, but not the greatest, power. The term goes back into the age of sail, although the usage differed from even the 20th century. Beyond that basic statement, the characteristics and roles of cruisers have varied greatly since the beginning of the 20th century, when the term was applied with some degree of formalism. The word "cruiser" was first used in English in 1651. Cognates in Dutch, Portuguese, and French meant "crossing", as in crossing back and forth across the entrance to a harbor to enforce a blockade, or crossing an ocean.[1]

The Naval vessel designation code for cruisers, and, for historical reasons, aircraft carriers, begin with the letter "C". Carriers were originally called aviation cruisers, and various post-WWII ships, by various names, carrying more than a pair of helicopters may be reviving the aviation cruiser concept.

One of today's challenges is that the definitions of three warship types: cruiser, destroyer, and ocean escort — have had changing and overlapping definitions, and even overlapping realization. The "frigate" of the age of sail had a role comparable to many modern cruiser roles, but a modern frigate is sometimes an ocean escort lighter than a destroyer or cruiser, perhaps on a merchant-grade hull. Alternatively, there may be no practical difference between frigates and destroyers. At one point, destroyers tended to have more potent anti-air warfare capability, but the French-Italian Horizons are "air warfare frigates".

It may be observed that the U.S. used the term "frigate" rather strangely between 1950 and 1975; see the time of the "cruiser gap". Literally the same basic hull is used for the Ticonderoga-class cruisers, the retired land attack and antisubmarine-optimized Spruance-class destroyers, and for the multirole but extremely strong antiair Burke-class destroyers. The "ocean escort" has had a wide range of names, but a fundamental mission of convoy escort, without the speed of vessels intended to fight other surface warships.

The U.S. and Russia are the only navies with ships designated as cruisers, and only the U.S. has actively discussed building new cruisers.

Classic Roles

Classic roles included:

- Foreign station ships, independently deployed, looked out for national interests around the world. In addition to an extensive gun armament, the station ship had self-repair capability, long range, and "first-responder-to-disorder" equipment such as small arms for the crew and an extensive boat outfit. The disorder could be a revolutionary situation or a natural disaster.

- Sea denial ships, using their pre-deployed location, attacked other nations' trade routes. Counter-raider merchant ship escorts would, in turn, try to stop enemy sea denial ships. In modern terms, this is anti-surface warfare (ASuW)

- Scout vessels, fast enough to run from what they could not fight, and heavily armed enough to defeat what they can catch.

Cruiser is certainly an older term than destroyer. As destroyers emerged, as well as light cruisers, one of the classic distinctions was that a cruiser had some armor but a destroyer had none.

The Royal Navy categorized sailing ships (i.e., three-masted) from the most powerful 1st rate to the light 6th rates; smaller fighting vessels, such as sloops and brigs, were not "rated". Parliamentary documents of 1694 show that 5th and 6th rate frigates were detached to "cruise" to protect friendly shipping, and to find hostile vessels. Ships of these rates had long endurance and high speed. They held to the general principle that they could run from any vessel heavily armed enough to defeat them, but were armed well enough to pursue and neutralize pirate and other commerce raiders. Their captains had sufficient rank to be trusted on independent operations.

While they could not survive in line of battle, they had important roles in fleet operations, as couriers, rescue vessels, scouts, and, after the Battle of the Saintes (1782), were often used as command ships that would not be tied to the line or be a tempting target.

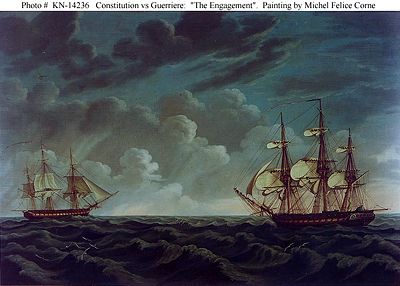

Cruisers, called frigates, played an important part in the War of 1812. On 2 August 1812, USS Constitution (44), sailing out of Boston to challenge the patrolling British frigates. Alerted by an American privateer, she met and sunk HMS Guerriere (38) on 19 August. Constitution is afloat today in Boston Harbor.

Evolved roles

Reconnaissance

Scouting is a traditional role. In WWII, the UK used cruisers, with radar and greater speed than battleships, to shadow capital ships and coordinate strikes. The Soviet Union assigned some of its cruisers, in the fifties and sixties, a similar role against U.S. carrier battle groups.

The scouting function is reflected in the U.S. ship type code, CV, for aircraft carriers. Some of the early aircraft carriers had 8" naval guns (203mm) for self-protection against other ships, that being considered a caliber fit for a heavy cruiser. As it became obvious that carriers would always be escorted, the heavier guns were removed from carriers with them, to make more space for aviation functions. Most subsequent carriers, through WWII, did have 5" dual-purpose guns; the latest carriers have, at most, autocannon for defense against speedboats or perhaps final point defense against air threats.

New Japanese "destroyer" designs will carry more than the usual two helicopters of a cruiser. Italian Andrea Doria class cruisers carried 6 helicopters. Discussions of ship designs underway also considering carrying a mixture of helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicles, the latter in both unarmed intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) and armed combat configurations.

Sea denial role

The idea of an independent balanced ship, or at least a small formation, has gone in and out of style. For blue water operations, however, aircraft and satellites can survey far more area than can a surface ship. Satellites, however, cannot attack surface targets, and aircraft have far less endurance than a ship.

It has been argued that the nuclear-powered submarine is the ultimate sea denial platform, but a submarine can only sink targets. Only ships can maintain a less-than-lethal blockade, as in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Blockades, anti-piracy operations and commerce raiding today, however, are more likely to take place in littoral waters, and a large ship such as a cruiser may not be ideal for the role unless its endurance is necessary.

Air and missile defense

In WWII, the CLAA type, a light cruiser with an exceptionally large number of 5" guns, met with only limited success. Had radar gun control been more advanced, they might have had a chance. A cruiser with good radar and good self-protection could, however, have a role in fighter direction. The most significant advantage of this design was that it was larger and had better sea-keeping characteristics than a destroyer, so it could escort carriers under any weather conditions.

A high-end modern destroyer could be as strong an anti-surface threat as a WWII heavy cruiser, and immensely more in anti-air warfare. For a time, however, a distinction was that cruisers had area air defense capability, while destroyers had local capability, more than self-defense but only extending to ships in close company.

Modern cruisers are the key escorts and escort command vessels for Carrier Strike Groups and amphibious warfare Expeditionary Strike Groups. In the U.S. Navy, the group anti-air warfare officer is usually on a Ticonderoga-class cruiser (designation code CG), which has both AEGIS battle management that a carrier does not, and more space for task group command functions than a destroyer.

Both Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Burke-class destroyers have a layered air defense system, with RIM-156 Standard SM-2 fired from vertical launch system cells for long range, RIM-162 ESSM four-packs for medium-range from the same cells, and RIM-116 Rolling Airframe Missile for final defense. The RAM replaces the Phalanx close-in weapons system autocannon, which is too slow and short-ranged to deal with supersonic sea-skimming misile threats.

It seems a given that new-generation U.S. cruisers will have a significant theater ballistic missile defense role. Nevertheless, any AEGIS ship, which can take the AN/SPY-2 radar upgrade potentially can use the SM-3 ABM; the Japanese Kongo-class destroyers are adding TBMD capability. Kongos, like the South Korean KDK's, are modified copies of Burke-class destroyers, not cruisers.

Russian cruisers also have area air defense missiles, the SA-N-6 variant of the S-300 air defense missile. The land-based version of this missile is designated SA-10 GRUMBLE by NATO.

As the Ticonderogas also have ESSM and RAM, the Russian ships have SA-N-4 GECKOs for medium range, and the Kashtan close-in weapons system. Kashtan is a unique combination of a short-range missile similar to RAM, on the same mount as an autocannon.

Command ship

Today's pure command ships have no independent combat capability, but, in WWII, it was found that ships that fired heavy guns tended to have their communications disrupted by the shock. Now that heavy guns are not present, combatant ships with the space for an officer at a higher level than a ship's captain logically would be on a carrier. Of course, this only applies to the U.S. and Russia, since no one else has cruisers. In U.S. doctrine, the group anti-air warfare officer will normally be aboard an AEGIS ship. The greater amount of command space on a Ticonderoga, and the concept of keeping these ships in the escort role than an independent platform would suggest that officer would be there.

Most command ships in use today have a "L" prefix, as they are most associated with amphibious warfare; the U.S. has three, one for each forward-deployed fleet. They are not, however, cruisers.

During part of the Cold War, two ships were designated as a National Emergency Command Post Afloat (NECPA). The idea of getting the President and National Command Authority safely airborne in the E4B "doomsday plane" or National Airborne Command Post (NEACP) is well known.

The airborne command post would be much harder for an enemy to attack than a ship, but the aircraft has much less endurance than a ship. While the command ships, the USS Northampton, modified from a cruiser, and USS Wright, modified from a carrier, would not fall from the sky if they ran out of lubricating oil, once Soviet ocean surveillance satellites and long-range anti-shipping missiles were available, it is hard to imagine that a ship less protected than is an aircraft carrier, with rings of escort vessels and aircraft, would be survivable. They were decomissioned in 1970. [2] Still, they demonstrated one more cruiser mission.

Land attack

Gunfire support was long a role of cruisers, where many believe their 8" and 6" guns were superior to the larger guns of battleships. The cruiser guns were faster-firing, as or more accurate, and their smaller shell size allowed them to fire in closer proximity to friendly forces.

With the advent of the vertical launch system on later Ticonderoga-class (i.e., CG 52 and higher) cruisers, the ships gained a significant land attack capability using the BGM-109 Tomahawk cruise missile. While Russian cruisers carry even larger P-700 Granit cruise missiles, they seem dedicated to the anti-shipping missile function.

The U.S. Navy, in contrast, retired the anti-shipping Tomahawk ASM. There was a planned land attack version of the Standard SM missile series, officially cancelled although the late-model SM-2 may have a comparable capability.

First World War and interwar

Scouting remained a role, independently, in small cruiser units, and for a fleet. Commerce raiding was also a mission, notably by German Admiral Maximilian von Spee's squadron, which also destroyed an inferior British cruiser squadron at the Battle of Coronel.

In the balance among speed, armament, and armor, cruisers favored speed above all. Cruiser armor did not meet one of the contemporary definitions of a battleship: armor proof against shells the same size as its main battery. There were continuing discussions during WWI about "battlecruisers" and about "large cruisers" afterwards. A British battlecruiser squadron under VADM Doveton Sturdee destroyed von Spee's force at the Battle of the Falklands.

It did become clear that using battlecruisers as part of a battle line, in the presence of battleships, was extremely unwise. A battlecruiser might find a battleship, but never fight one. At the Battle of Jutland, when British battlecruisers commanded by ADM David Beatty faced German battleships, the battlecruisers HMS Queen Mary and HMS Indefatigable blew up and sank. Beatty commented to his flag captain, "There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.[3]

Cruisers did not take on a significant antisubmarine role, even though one of the first actions in the war involved three British cruisers, HMS Aboukir, HMS Cressy and HMS Hogue being sunk by the German submarine U-9. [4]

Another confusing designation was "armed merchant cruiser", which was a converted civilian ship, sometimes a liner with high speed, but no armor at all, and guns added as an afterthought, with minimal fire control.

After the war, naval arms reduction went into place. Language in The London Treaty of 1930 finally provided an objective definition of one cruiser type. The heavy cruiser, also known as an armored cruiser (CA) or first class cruiser, was specified as having a 6.1/155mm to 8" naval gun (203mm) inch main battery. They were also limited in displacement to 10,000 tons.

Heavy cruisers are generally a post-First World War design. A few examples of "first class protected cruisers" or "semi-armored cruiser" previously existed; they had the armament of heavy cruisers but lighter armor.

Designs for, and operations in, WWII

U.S. WWII cruisers were extremely valuable, but in roles different than had first been conceived. One role centered around destroyers attacking with torpedoes; the U.S. saw the cruisers as leading U.S. attacks or defending against enemy attacks of this type. They were also expected to operate independently, both in raiding and in presence on the lines of communications in the Pacific.

They actually had little independent role, but screened the carrier task forces primarily against aircraft, and bombarded shore targets both in raids and in amphibious support.[5] There were some major cruiser engagements, some disastrous, such as the Battle of Savo Island.

Most cruisers were in commission before the war. The U.S. did launch the USS Baltimore, a 14,500 ton heavy cruiser, in 1943. There were 17 ships in this class, several of which were converted to guided missile cruisers after the war.

Cruiser actions were most significant in the early part of the war; aircraft and submarines became the decisive arm in later years.

Battle of the River Plate

The German "pocket battleship", DKM Graf Spee, was an advanced design 16,200 ton design, heavily armed with (6×11 inch/280 mm, 8×5.9 inch/150 mm)[6] She had a long run of commerce raiding, but was eventually confronted by three British cruisers in December 1939:

- heavy cruiser HMS Exeter (8,400 ton 6×8-inch/203mm)

- light cruiser HMS Ajax (7,000 tons, 8×6-inch/152mm)

- light cruiser HMZNS Achilles (7,000 tons, 8×6-inch/152mm)

Graf Spee was critically damaged, and put into the neutral harbor of Montevideo, Uruguay on December 17. She was unable to repair her damage while in port, and, believing a heavy British squadron was on the way, her captain, Hans Lansdorff, ordered her scuttled. After his men were safely off, he returned to his hotel room, wrapped himself in the Imperial German naval ensign, and shot himself on December 20.

Raids

RADM Raymond Spruance took the cruisers USS Northampton and USS Salt Lake City, and a destroyer, and bombarded Wotje in Kwajalein Atoll on February 1. Next, they escorted carrier raids against Wake Island and Marcus Island, and the New Guinea bases, Lae and Salamaua. USS Vincennes (CA-44) and USS Nashville were the heavy ships of the escort of the Doolittle Raid in April, and were involved in sinking a picket boat.

Battle of the Java Sea

The cruisers USS Houston (heavy), USS Marblehead (light), and USS Boise (light) fought with the American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) command under Dutch Admiral Karel Doorman in a vain attempt to stop the Japanese advance into the Java Sea in February 1942.[5]

Battle of Savo Island

In the Battle of Savo Island in August 1942 three American cruisers USS Astoria (CA-34), USS Quincy (CA-39), and USS Vincennes (CA-44) as well as the Australian cruiser HMAS Canberra were lost in a Japanese night attack.[5]

Two groups of Allied warships were protecting 19 transports anchored in the Guadalcanal area. Savo Island lies between the two larger masses. They were under the command of Australian RADM V.A.C. Crutchley, who was not present; he had taken his flagship, HMAS Australia, to attend a conference with the overall commander, RADM Richmond Turner, USN.

The Japanese 8th Fleet, under VADM Misawa, combined the heavy cruisers IJN Chokai, IJN Aoba, Kinugasa, Kako, and Furutaka with the light cruisers Tenryu and Yubari, and the destroyer Yunagi.

Sydney vs. Kormoran

One of the mysteries of the Second World War, partially solved in 2008, was the engagement between the Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney II and the German auxiliary cruiser DKM Kormoran.[7] DKM Kormoran was a commerce raider, whose mission was not to fight warships. They met off Western Australia, 150 miles southwest of Carnavon.

For reasons still not completely understood, HMAS Sydney closed to very short range while suspicious that Kormoran was not a merchant ship. Unable to give the correct identification signal, Kormoran opened heavy fire, and inflicted critical damage. Nevertheless, Sydney returned fire and mortally damaged the Kormoran. The two drifted apart; the captain of the Kormoran ordered her abandoned, with a loss of 80 lives.

Sydney was last seen drifting away, burning. She was never seen again, until discovered, on the ocean floor, in 2008. All of her 645 men were lost. The two ships were found, approximately 112 nautical miles off Steep Point, Western Australia. Kormoran is lying at a depth of 2,560 metres; Sydney, approximately 12 nautical miles away, is at 2,470 metres.

Speculation as to why Sydney came so close varied from the inexperience of her captain, to a feigned German surrender, to a cooperating Japanese submarine. [8]

Postwar

U.S. Des Moines class

Discussions of postwar cruisers tend to focus on the conversions to guided missile cruisers and new-construction guided missile cruisers, and ignore the last of these gun cruisers. Since they had a far higher rate of fire than earlier heavy cruisers, they provided exceptional naval gunfire support to ground troops.

Three heavy cruisers, modified from the Boston-class, were commissioned after WWII: USS Des Moines, USS Salem, and USS Newport News. They were larger (17,000 tons) than the Baltimores. All, at one time or another, were flagship of the United States Sixth Fleet, although admirals probably preferred to be on the Newport News and Salem (CA 138), which were air conditioned. The namesake of the class, Des Moines (CA 134), was not.

This class had a new type of semi-automatic 8-inch/203mm gun. Only Newport News (CA 148), commissioned in Jan 1949, used her big guns extensively, and that was on the gun line in Vietnam. [5] USS Newport News was one of the few ships to be in an extended exchange with North Vietnamese shore batteries.[9]

Soviet Sverdlovsk class

In the early fifties, the Soviet Union built 13 Sverdlovsk-class with twelve 6-inch/152mm guns in triple turrets. They were generally considered obsolescent when built, and the planned 30 ship construction was cut off. Some were used as missile test ships or command ships, others converted for command vessels, and others transferred to other countries.

The time of the "cruiser gap"

Designations get extremely confusing during this period, both because the Soviet Union and the U.S. might well have different names for a ship with the same basic capabilities, and there were also some new concepts that did not fit into any designation of the past. In this section, all-gun cruisers such as the Des Moines and Sverdlovsk do not enter into the discussion.

During some of this time, there was a perception of a "cruiser gap" between the U.S. and U.S.S.R., because, using certain U.S. terminology, there was a time that the U.S. called six of its ships "cruisers" while the Soviets used the term for 19 of theirs. In actuality, 17 of the Soviet vessels were comparable or weaker than a U.S. group of 10 ships, which were redesignated several times.

United States

After WWII, the Navy's new ship construction budget went mostly to aircraft carrers. There was, however, a large number of cruisers, and the role of all-gun cruisers was rapidly reducing, except for some with unusually fast-firing big guns useful for shore bomardment. While a number of cruisers were converted, typically with compromises since they were not designed as missile ships, some of the large gun cruisers were kept for their value as command ships and stable radar platforms.[10]

Albany class large missile cruiser

While there were occasional revivals of battleships, principally in gunfire support roles, the U.S. Navy defined cruisers as its primary surface combatants. As with current definitions, such a vessel had a long-range area air defense capability, which would be based on the RIM-8 Talos SAM. A cruiser was to be assigned, as a major escort, to each carrier battle group.

Large missile cruisers were converted from completely stripped hulls of Baltimore and Oregon City class heavy gun cruisers. The result was a 17,500 ton ship, of which three were commissioned, starting with the USS Albany in 1956 and followed by USS Chicago and USS Columbus, vessels conceptually differed from the many-named 5,800-ton Farragut/Coontz ships in an additional system besides the longer-ranged SAM.

In the conversion, all guns were removed, Talos launchers mounted in the fore and aft gun positions, RIM-24 Tartar on the sides, and a launcher for ASROC anti-submarine rockets was located amidships. These large missile cruisers could carry deep-strike nuclear missiles, either the RGM-6 Regulus (essentially a larger, faster, nuclear-armed V-1) cruise missile or the same UGM-27 Polaris used as a submarine-launched ballistic missile. No surface ship, however, was ever fitted with either of these deep-strike systems.

It might be observed that the BGM-109 Tomahawk, on the Ticonderoga-class cruisers is a far more capable cruise missile that can carry a W80 nuclear weapon, but there is an agreement between the U.S. and Russia that sea-based cruise missiles will stay conventionally armed.

United States: chaos

The truly confusing vessel designation from this period which was a "frigate", a task force escort between the size of a WWII destroyer and cruiser. Frigates would not carry deep-strike weapons, so would be less expensive than the cruisers. Rather than the longest-range RIM-8 Talos, their SAM system would be the mid-range RIM-2 Terrier.

One cruiser was to be assigned to each carrier group. There were relatively few of these ships, due to their cost and that the new-build smaller "frigates" had almost as many weapons, admittedly with a shorter-ranged SAM. From 1950 to 1975, what the Navy called, for a time, "frigates" were a new type, a 5800 ton ship. The first hull laid down was the USS Farragut, followed by her sisters USS Luce and USS Macdonough. Their armament of these three started out as three dual 5"/38 mounts, two in the forward "A" and "B" positions and one in the astern "X" position. In these three ships, the "B" gun position was converted to a Terrier launcher, and the "X" position to an ASROC launcher.

USS Coontz was to be the fourth of the 5800 ton hulls, but was actually commissioned before the Farragut. Schedules worked out that the Coontz not converted from three gun positions, but immediately had the "A" gun, "B" Terrier, and "X" ASROC.

Soviet

The Soviets stayed with more traditional types, and never hesitated to have a clear difference between destroyers and cruisers. Remember that the U.S. Farragut/Coontz were called everything but cruisers. So, by 1974, the U.S. had only six ships called cruisers, while the Soviets had 19 ships called cruisers.

In actuality, most of the Soviet "cruisers" were comparable to the Farragut/Coontz vessels, not the much larger vessels the U.S. called cruisers. The Soviets also had all-gun Sverdlovsk light cruisers, while the U.S. had the Des Moines heavy cruisers.

All but two of the Soviet ships were relatively small vessels, roughly equivalent to US frigates (of the time) and far smaller than US cruisers. The differing US and Soviet definitions of "cruiser" caused problems when comparisions were made between US and Soviet naval forces. Using the different definitions, however, it was possible to say there 6 US cruisers versus 19 Soviet cruisers.

Post-1975

Cruisers became increasingly rare in the seventies; only the US and USSR had significant numbers. Individual cruisers were prestigious vessels in some small navies; the ex-USS Phoenix, last operational warship that survived the Battle of Pearl Harbor, was transferred to Argentina. During the Falklands War, ARA General Belgrano, veteran of Pearl Harbor, did not survive the torpedoes of the nuclear submarine HMS Conqueror.

US

- See also: Ticonderoga-class

Rationality returned on 30 Jone 1975. Guided missile frigates (DLG) all became either guided missile destroyers (DDG) or guided missile cruisers (CG). All the "destroyer leaders" except the Farragut/Coontz class were redesignated as guided missile cruisers:

- Virginia

- California

- Truxton

- Belknap

- Bainbridge

- Leahy

The Coontz Class was redesignated as Guided Missile Destroyers (DDG). "Frigate" changed from a term for a moderately large ship to the name of the "ocean escorts" that were "destroyer escorts" during WWII.

In 1980, the DDG-47 class were redesignated missile cruisers of the Ticonderoga class. The same hulls were also used for the Spruance-class land attack destroyers and the early Burke class air defense (and then multirole destroyers).

The first five did not have the Vertical Launch System (VLS) for missiles, and have all been retired. The remaining 22 are extremely powerful ships, although, in some respects, Burke class destroyers, which have had several "flights" or subclasses, may be more potent. "Ticos" are generally assumed to be escorts to Carrier Strike Groups or the core of Expeditionary Strike Groups. In a carrier group, the overall group commander is usually aboard the carrier, while the group anti-air officer is apt to be on a Tico.

According to the US Navy, a cruiser had the principal mission of AAW, and was focused on providing air defense to an aircraft carrier. As well as having more VLS tubes, the Tico has an additional very-long-range air search radar that the Burke does not, and one more final missile guidance radar than a Burke. The latter are time-shared in any case, so either ship class can control more missiles than they have illuminators. With an AEGIS feature called Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC), a given AEGIS system can guide SM-2 SAMs fired by other ships in the formation, so as long as a Burke had the Mark 99 launch control system working, it could fire SAMs "blind" and have another AEGIS vessel control them. Assuming the Burke also has CEC, however, the reverse could be true; the SAMs could be launched by a Tico and controlled by a Burke. In the Gulf War, the USS San Jacinto (CG-56), a Tico, was designated the "special weapons platform", carryin 122 Tomahawks. The normal Tico loadout is 12 Tomahawks and 110 SM-2.

Burkes definitely have more antisubmarine warfare capability than Ticos. It is not known if they carry VL-ASROC in their VLS and the Tico does not.

While both classes have VLS tubes that can launch Tomahawks, and the Ticos have more tubes, the Navy, perhaps in a reversal of roles, let the Burke take multiple roles. These roles are either carrier escort, or independent Tomahawk-shooter. The Burke, therefore, was made more survivable than the Tico, since Tomahawk launching needs little sensor help from the launching vessel. SM-2 and SM-3 SAMs and ABMs, however, must have the support of the full AEGIS system. Thus the DDG received a steel superstructure, increased blast overpressure resistance, more armor, a collective protection system and radar cross section reduction measures. Thus there is a historically anomalous situation of the destroyer being a more survivable ship than the cruiser. "[11]

Soviet/Russian

- See also: Kirov-class

The Soviet Union had several families of cruisers, but only two remaining after the USSR broke up. Kirov/Admiral Ushakov ships have been argued as the most powerful surface units in the world, and their massive anti-shipping missiles are unmatched, probably intended as carrier killers. On the other hand, their electronics and air defense missiles may be inferior to the AEGIS system.

| Soviet class | Russian class | Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Kirov | Admiral Ushakov | Nuclear propulsion, large, balanced, 2 active, probably carrier killer |

| Slava | Moskva | Balanced; simpler Kirov; 3 active |

| Kara | Kara | ASW & command; 2 in Black Sea |

| Kresta II | Retired by 1993 | ASW |

| Kresta I | Retired by 1995 | ASuW |

| Kynda | Retired by 2002 | ASuW, succeeded by Kresta I |

Admiral Ushakovs continue to evolve. They have had the Kashtan close-in weapons system added to replace pure gun defenses. Individual ships have more or less 130mm guns vice antisubmarine weapons.

References

- ↑ Priest, Karl C., Ghosts of the East Coast: Doomsday Ships

- ↑ Admiral of the Fleet Sir David Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty 1871-1936, Royal Navy

- ↑ Loss of HMS Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 CA-134 Des Moines

- ↑ Only guns with caliber greater than 4-inch/102mm are mentioned here

- ↑ HMAS Sydney II and the Kormoran: The action between HMAS Sydney and the auxiliary cruiser Kormoran, 19 November 1941, Australian War Memorial

- ↑ "The Hunt for HMAS Sydney: Alternate Theories", ABC News

- ↑ Thunder goes to War

- ↑ Eisenberg, Michael T. (1993), Shield of the Republic, Volume I (1945-1962), St. Martin's Press pp. 369-375

- ↑ Cruisers in the Cold War - 1945-1990, Globalsecurity