Aristotle

Aristotle (Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης, Aristotélēs) (384 BCE – March 7, 322 BCE) was an ancient Greek philosopher, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. He wrote books on diverse subjects, including physics, poetry, zoology, logic, rhetoric, politics, government, and biology, none of which survive in their entirety. Aristotle, along with Plato and Socrates, is generally considered one of the most influential of ancient Greek philosophers. They transformed Presocratic Greek philosophy into the foundations of Western philosophy as we know it. The writings of Plato and Aristotle founded two of the most important schools of Ancient philosophy.

Although Aristotle wrote dialogues early in his career, only fragments of these have survived. The works of Aristotle that exist today are in treatise form and were mostly unpublished texts, generally thought to be lecture notes or texts used by his students. Among the most important are Physics, Metaphysics (or Ontology), Nicomachean Ethics, Politics, De Anima (On the Soul) and Poetics. These works, although connected in many fundamental ways, differ significantly in both style and substance.

Aristotle studied almost every subject possible at the time, probably being one of the first polymaths. In science, Aristotle studied anatomy, astronomy, economics, embryology, geography, geology, meteorology, physics, and zoology. In philosophy, Aristotle wrote on aesthetics, ethics, government, metaphysics, politics, psychology, rhetoric and theology. He also dealt with education, foreign customs, literature and poetry. His combined works practically constitute an encyclopedia of Greek knowledge.

Biography

Early life and studies at the Academy

Aristotle was born in a colony of Andros on the Macedonian peninsula of Chalcidice in 384 BCE. His father, Nicomachus, was court physician to King Amyntas III of Macedon; it is believed that Aristotle's ancestors held this position under various kings of the Macedons. Little is known of his mother, Phaestis; she died while Aristotle was very young. When Nicomachus also died, in Aristotle's tenth year, he was placed under the guardianship of his uncle, Proxenus of Atarneus, who taught Aristotle Greek, rhetoric, and poetry (O'Connor et al., 2004). Aristotle also attended Plato's school for young Greek aristocracy, and became Plato's favourite student. Aristotle was also influenced by his father's medical knowledge; when he went to Athens at the age of 18, he was likely already trained in the investigation of natural phenomena.

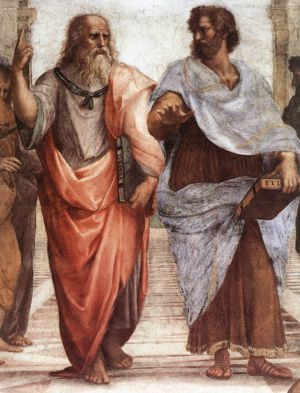

From the age of 18 to 37, Aristotle remained in Athens as a pupil of Plato and distinguished himself at the Academy. The relations between Plato and Aristotle have been the subject of various legends, many of which depict Aristotle unfavourably. No doubt there were divergences of opinion between Plato, who took his stand on sublime, idealistic principles, and Aristotle, who even then showed a preference for the investigation of the facts and laws of the physical world. It is also probable that Plato suggested that Aristotle needed restraining rather than encouragement, but not that there was an open breach of friendship. In fact, Aristotle's conduct after the death of Plato, his continued association with Xenocrates and other Platonists, and his allusions in his writings to Plato's doctrines prove that while there were conflicts of opinion between Plato and Aristotle, there was no lack of cordial appreciation or mutual forbearance. The legends that reflect unfavourably on Aristotle are allegedly traceable to the Epicureans, although some doubt remains of this charge. If such legends were circulated widely by patristic writers such as Justin Martyr and Gregory Nazianzen, the reason lies in the exaggerated esteem Aristotle was held in by the early Christian heretics.

Aristotle as philosopher and tutor

After Plato's death in 347 BCE, Aristotle was considered as the next head of the Academy, a position eventually awarded to Plato's nephew. Aristotle then went with Xenocrates to the court of Hermias, ruler of Atarneus in Asia Minor, married his niece, Pythias, and with her had a daughter named Pythias after her mother. In 344 BCE, Hermias was murdered in a rebellion, and Aristotle went with his family to Mytilene. It is reported that he stopped on Lesbos and briefly conducted biological research. Then, one or two years later, he was summoned to Pella, the Macedonian capital, by King Philip II of Macedon to become the tutor of Alexander the Great, who was then 13.

Plutarch wrote that Aristotle imparted to Alexander a knowledge of ethics and politics, and the 'most profound secrets' of philosophy. Alexander profited by contact with the philosopher, and Aristotle made prudent and beneficial use of his influence over the young prince (although Bertrand Russell disputes this). Alexander provided Aristotle with ample means for the acquisition of books and the pursuit of his scientific investigation. It is possible that Aristotle also participated in the education of Alexander's boyhood friends, which may have included Hephaestion and Harpalus. Aristotle maintained a long correspondence with Hephaestion, eventually collected into a book, unfortunately now lost.

According to Plutarch and Diogenes, Philip had Aristotle's hometown of Stageira burned during the 340s BCE, and Aristotle successfully requested that Alexander rebuild it. During his tutorship of Alexander, Aristotle was reportedly considered a second time for leadership of the Academy; his companion Xenocrates was selected instead.

Founder and master of the Lyceum

In about 335 BCE, Alexander departed for his Asiatic campaign, and Aristotle, who had been his informal adviser (more or less) since Alexander ascended the Macedonian throne, returned to Athens and opened his own school of philosophy. He may, as Aulus Gellius says, have conducted a school of rhetoric during his former residence in Athens; but now, following Plato's example, he gave regular instruction in philosophy in a gymnasium dedicated to Apollo Lyceios, from which his school came to be known as the Lyceum. (It was also called the Peripatetic School because Aristotle preferred to discuss problems of philosophy with his pupils while walking around -- peripateo -- the shaded walks -- peripatoi -- around the gymnasium).

Aristotle composed most of his writings in the thirteen years (335 BCE–322 BCE) that he spent as teacher of the Lyceum. Imitating Plato, he wrote Dialogues in which his doctrines were expounded in somewhat popular language. He also composed treatises on physics, metaphysics, and so forth, in which the exposition is more didactic and the language more technical than in the Dialogues. These writings succeeded in bringing together the works of his predecessors in Greek philosophy, and how he pursued, either personally or through others, his investigations in the realm of natural phenomena. Pliny the Elder claimed that Alexander placed under Aristotle's orders all the hunters, fishermen, and fowlers of the royal kingdom and all the overseers of the royal forests, lakes, ponds and cattle-ranges, and Aristotle's works on zoology make this statement more believable. Aristotle was fully informed about the doctrines of his predecessors, and Strabo asserted that he was the first to accumulate a great library.

In the last years of his life, relations between Aristotle and Alexander were strained, owing to the disgrace and punishment of Callisthenes, whom Aristotle had recommended to Alexander. Nevertheless, Aristotle continued to be regarded in Athens as a friend of Alexander and a representative of Macedonia. Consequently, when Alexander's death became known in Athens, and the outbreak occurred which led to the Lamian war, Aristotle shared in the general unpopularity of the Macedonians. The charge of impiety, which had been brought against Anaxagoras and Socrates, was now brought against Aristotle. He left the city, saying, "I will not allow the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy" (Vita Marciana 41). He took up residence at his country house at Chalcis, in Euboea, and died there the following year, 322 BCE. His death was due to a disease, reportedly 'of the stomach', from which he had long suffered; the story that his death was due to hemlock poisoning, as well as the legend that he threw himself into the sea "because he could not explain the tides," are without historical foundation.

Aristotle's legacy had a profound influence on Islamic thought and philosophy during the Middle Ages. Muslim thinkers such as Avicenna, Al-Farabi, and Yaqub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi[1] were a few of the major proponents of the Aristotelian school of thought during the Golden Age of Islam.

Methodology

Template:Details Aristotle defines his philosophy in terms of essence, saying that philosophy is "the science of the universal essence of that which is actual". Plato had defined it as the "science of the idea", meaning by idea what we should call the unconditional basis of phenomena. Both pupil and master regard philosophy as concerned with the universal; Aristotle, however, finds the universal in particular things, and called it the essence of things, while Plato finds that the universal exists apart from particular things, and is related to them as their prototype or exemplar. For Aristotle, therefore, philosophic method implies the ascent from the study of particular phenomena to the knowledge of essences, while for Plato philosophic method means the descent from a knowledge of universal ideas to a contemplation of particular imitations of those ideas. In a certain sense, Aristotle's method is both inductive and deductive, while Plato's is essentially deductive from a priori principles.

For Aristotle, the term natural philosophy corresponded to the phenomena of the natural world, including motion, light, and the laws of physics. Many centuries later, these subjects would become the basis of modern science, and in modern times the term philosophy has come to be more narrowly understood as metaphysics, distinct from empirical study of the natural world via the physical sciences. However, for Aristotle, philosophy encompassed all facets of intellectual inquiry, and he made philosophy coextensive with reasoning, which he also called "science". His use of the term science has a different meaning to that which is covered by the scientific method. "All science (dianoia) is either practical, poetical or theoretical". By 'practical' science, he means ethics and politics; by 'poetical', he means the study of poetry and the other fine arts; while by 'theoretical philosophy' he means physics, mathematics, and metaphysics, defined as "the knowledge of immaterial being", the "first philosophy", "the theologic science" or of "being in the highest degree of abstraction". If logic, or, as Aristotle calls it, Analytic, is regarded as a study preliminary to philosophy, we have as divisions of Aristotelian philosophy

- (1) Logic;

- (2) Theoretical Philosophy, including Metaphysics, Physics, Mathematics,

- (3) Practical Philosophy; and

- (4) Poetical Philosophy.

Aristotle's epistemology

Logic

Aristotle's conception of logic was the dominant form of logic up until the advances in mathematical logic in the 19th century. Kant himself thought that Aristotle had done everything possible in terms of logic.

History

Aristotle "says that 'on the subject of reasoning' he 'had nothing else on an earlier date to speak of'" (Bocheński, 1951). However, Plato reports that syntax was thought of before him, by Prodikos of Keos, who was concerned by the right use of words. Logic seems to have emerged from dialectics; the earlier philosophers used concepts like reductio ad absurdum as a rule when discussing, but never understood its logical implications. Even Plato had difficulties with logic. Although he had the idea of constructing a system for deduction, he was never able to construct one. Instead, he relied on his dialectic, which was a confusion between different sciences and methods (Bocheński, 1951). Plato thought that deduction would simply follow from premises, so he focused on having good premises so that the conclusion would follow. Later on, Plato realized that a method for obtaining the conclusion would be beneficial. Plato never obtained such a method, but his best attempt was published in his book Sophist, where he introduced his division method (Rose, 1968).

Analytics and the Organon

What we today call Aristotelian logic, Aristotle himself would have labelled 'analytics'; he reserved the term 'logic' to mean dialectics. Most of Aristotle's work is probably not in its original form, as it was probably edited by students and later lecturers. His logical works were compiled into six books in about the early 1st century CE:

- Categories

- On Interpretation

- Prior Analytics

- Posterior Analytics

- Topics

- On Sophistical Refutations

The order of the books (or the teachings from which they are composed) is not certain, but this list was derived from analysis of Aristotle's writings. It goes from the basics, the analysis of simple terms in the Categories, to the study of more complex forms, namely, syllogisms (in the Analytics) and dialetics (in the Topics and Sophistical Refutations). There is one volume of Aristotle's concerning logic not found in the Organon, namely the fourth book of Metaphysics. (Bocheński, 1951).

Modal logic

Aristotle is also the creator of syllogisms with modalities (modal logic). The word modal refers to the word 'modes', explaining the fact that modal logic deals with the modes of truth. Aristotle introduced the qualification of 'necessary' and 'possible' premises. He constructed a logic which helped in the evaluation of truth but which was difficult to interpret. (Rose, 1968).

Science

Aristotelian discussions about science had only been qualitative, not quantitative. By the modern definition of the term, Aristotelian philosophy was not science, as this worldview did not attempt to probe how the world actually worked through experiment. For example, in History of Animals he claimed that human males have more teeth than females; had he only made some observations, he would have discovered that this is false. Rather, based on what one's senses told one, Aristotelian philosophy then depended upon the assumption that man's mind could elucidate all the laws of the universe, based on simple observation through reason alone. One reason for this was that Aristotle held that physics was about changing objects with a reality of their own, whereas mathematics was about unchanging objects without a reality of their own. In this philosophy, he could not imagine that there was a relationship between them. By contrast, today's science assumes that thinking alone often leads people astray, and therefore one must compare one's ideas to the actual world through experimentation; only then can one discern if one's hypothesis corresponds to reality.

Although Aristotle should be credited for an important step in the history of scientific method by founding logic as a formal science, he posited a flawed cosmology that we may discern in selections of the Metaphysics. His cosmology would gain much acceptance up until the 1500s. From the 3rd century to the 1500s, the dominant view was that the Earth was the centre of the universe.

Aristotle's metaphysics

Causality

In Metaphysics and Posterior Assilistics, Aristotle argued that all causes of things are beginnings; that we have scientific knowledge when we know the cause; that to know a thing's existence is to know the reason for its existence. He was the first who set the guidelines for all the subsequent causal theories by specifying the number, nature, principles, elements, varieties, and order of causes as well as the modes of causation. According to Aristotle, causes fall into several groups, which amount to the ways in which the question 'why' may be answered; namely by reference to the matter or the substratum; the essence, the pattern, the form, or the structure; the primary moving change or the agent and its action; the goal, the plan, the end, or the good. As a consequence, the major kinds of causes come under the following divisions:

The Material Cause is that from which a thing comes into existence as from its parts, constituents, substratum or materials. This reduces the explanation of causes to the parts (factors, elements, constituents, ingredients) forming the whole (system, structure, compound, complex, composite, or combination) (the part-whole causation).

The Formal Cause tells us what a thing is, that any thing is determined by the definition, form, pattern, essence, whole, synthesis, or archetype. It embraces the account of causes in terms of fundamental principles or general laws, as the whole (macrostructure) is the cause of its parts (the whole-part causation).

The Efficient Cause is that from which the change or the ending of the change first starts. It identifies 'what makes of what is made and what causes change of what is changed' and so suggests all sorts of agents, nonliving or living, acting as the sources of change or movement or rest. Representing the current understanding of causality as the relation of cause and effect, this covers the modern definitions of 'cause' as either the agent or agency or particular events or states of affairs.

The Final Cause is that for the sake of which a thing exists or is done, including both purposeful and instrumental actions and activities. The final cause or telos is the purpose or end that something is supposed to serve, or it is that from which and that to which the change is. This also covers modern ideas of mental causation involving such psychological causes as volition, need, motivation, or motives, rational, irrational, ethical, all that gives purpose to behavior.

Additionally, things can be causes of one another, causing each other reciprocally, as hard work causes fitness and vice versa, although not in the same way or function, the one is as the beginning of change, the other as the goal. Thus Aristotle first suggested a reciprocal or circular causality as a relation of mutual dependence or action or influence of cause and effect. Also, Aristotle indicated that the same thing can be the cause of contrary effects, its presence and absence may result in different outcomes.

Aristotle marked two modes of causation: proper (prior) causation and accidental (chance) causation. All causes, proper and incidental, can be spoken as potential or as actual, particular or generic. The same language refers to the effects of causes, so that generic effects assigned to generic causes, particular effects to particular causes, operating causes to actual effects. Essentially, causality does not suggest a temporal relation between the cause and the effect.

All further investigations of causality will be consisting in imposing the favorite hierarchies on the order causes, like as final > efficient> material > formal (Thomas Aquinas), or in restricting all causality to the material and efficient causes or to the efficient causality (deterministic or chance) or just to regular sequences and correlations of natural phenomena (the natural sciences describing how things happen instead of explaining the whys and wherefores).

Chance and spontaneity

Spontaneity and chance are causes of effects. Chance as an incidental cause lies in the realm of accidental things. It is "from what is spontaneous" (but note that what is spontaneous does not come from chance). For a better understanding of Aristotle's conception of "chance" it might be better to think of "coincidence": Something takes place by chance if a person sets out with the intent of having one thing take place, but with the result of another thing (not intended) taking place. For example: A person seeks donations. That person may find another person willing to donate a substantial sum. However, if the person seeking the donations met the person donating, not for the purpose of collecting donations, but for some other purpose, Aristotle would call the collecting of the donation by that particular donator a result of chance. It must be unusual that something happens by chance. In other words, if something happens all or most of the time, we cannot say that it is by chance.

However, chance can only apply to human beings, it is in the sphere of moral actions. According to Aristotle, chance must involve choice (and thus deliberation), and only humans are capable of deliberation and choice. "What is not capable of action cannot do anything by chance" (Physics, 2.6).

Substance, Potentiality and Actuality

Aristotle examines the concept of substance (ousia) in his Metaphysics, Book VII and he concludes that a particular substance is a combination of both matter and form. As he proceeds to the book VIII, he concludes that the matter of the substance is the substratum or the stuff of which is composed e.g. the matter of the house are the bricks, stones, timbers etc., or whatever constitutes the potential house. While the form of the substance, is the actual house, namely ‘covering for bodies and chattels’ or any other differentia. The formula that gives the components is the account of the matter, and the formula that gives the differentia is the account of the form (Metaphysics VIII, 1043a 10-30).

With regard to the change (kinesis) and its causes now, as he defines in his Physics and On Generation and Corruption, he distinguishes the coming to be from

- 1. growth and diminution, which is change in quantity

- 2. locomotion, which change in space and

- 3. alteration, which is change in quality.

The coming to be is a change where nothing persists of which the resultant is property. In that particular change he introduces the concept of potentiality (dynamis) and actuality (entelecheia) in association with the matter and the form.

Referring to potentiality, is what a thing is capable of doing, or being acted upon, if it is not prevented from something else. For example, a seed of a plant in the soil is potentially (dynamei) plant, and if is not prevented by something, it will become a plant. Potentially beings can either 'act' (poiein) or 'be acted upon' (paschein), as well as can be either innate or come by practice or learning. For example, the eyes possess the potentiality of sight (innate - being acted upon), while the capability of playing the flute can be possessed by learning (exercise - acting).

Referring now to actuality, this is the fulfillment of the end of the potentiality. Because the end (telos) is the principle of every change, and for the sake of the end exists potentiality, therefore actuality is the end. Referring then to our previous example, we could say that actuality is when the seed of the plant becomes a plant.

“ For that for the sake of which a thing is, is its principle, and the becoming is for the sake of the end; and the actuality is the end, and it is for the sake of this that the potentiality is acquired. For animals do not see in order that they may have sight, but they have sight that they may see.” (Aristotle, Metaphysics IX 1050a 5-10).

In conclusion, the matter of the house is its potentiality and the form is its actuality. The Formal Cause (aitia) then of that change from potential to actual house, is the reason (logos) of the house builder and the Final Cause is the end, namely the house itself. Then Aristotle proceeds and concludes that the actuality is prior to potentiality in formula, in time and in substantiality.

With this definition of the particular substance (matter and form) Aristotle tries to solve the problem of the unity of the beings; e.g., what is that makes the man one? Since, according to Plato there are two Ideas: animal and biped, how then is man a unity? However, according to Aristotle, the potential being (matter) and the actual one (form) are one and the same thing. (Aristotle, Metaphysics VIII 1045a-b).

The five elements

- Fire, hot and dry.

- Earth, cold and dry.

- Air, hot and wet.

- Water, cold and wet.

- Aether, the divine substance that makes up the heavenly spheres and heavenly bodies (stars and planets).

Each of the four earthly elements has its natural place; the earth at the centre of the universe, then water, then air, then fire. When they are out of their natural place they have natural motion, requiring no external cause, which is towards that place; so bodies sink in water, air bubbles up, rain falls, flame rises in air. The heavenly element has perpetual circular motion.

Aristotle's ethics

Although Aristotle wrote several works on ethics, the major one was the Nicomachean Ethics, which is considered one of Aristotle's greatest works; it discusses virtues. The ten books which comprise it are based on notes from his lectures at the Lyceum and were either edited by or dedicated to Aristotle's son, Nicomachus.

Aristotle believed that ethical knowledge is not certain knowledge, like metaphysics and epistemology, but general knowledge. Also, as it is a practical discipline rather than a theoretical one; he thought that in order to become "good", one could not simply study what virtue is; one must actually do virtuous deeds. In order to do this, Aristotle had first to establish what was virtuous. He began by determining that everything was done with some goal in mind and that goal is 'good.' The ultimate goal he called the Highest Good.

Aristotle contended that happiness could not be found only in pleasure or only in fame and honor. He finally finds happiness "by ascertaining the specific function of man". But what is this function that will bring happiness? To determine this, Aristotle analyzed the soul and found it to have three parts: the Nutritive Soul (plants, animals and humans), the Perceptive Soul (animals and humans) and the Rational Soul (humans only). Thus, a human's function is to do what makes it human, to be good at what sets it apart from everything else: the ability to reason or Nous. A person that does this is the happiest because they are fulfilling their purpose or nature as found in the rational soul. Depending on how well they did this, Aristotle said people belonged to one of four categories: the Virtuous, the Continent, the Incontinent and the Vicious.

Aristotle believed that every ethical virtue is an intermediate condition between excess and deficiency. This does not mean Aristotle believed in moral relativism, however. He set certain emotions (e.g., hate, envy, jealousy, spite, etc.) and certain actions (e.g., adultery, theft, murder, etc.) as always wrong, regardless of the situation or the circumstances.

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle often focused on finding the mean between two extremes of any particular subject; whether it be justice, courage, wealth and so forth. For example; too much courage can be a bad trait because it leads to ignorant choices, and too little courage would mean one is prone to cowardice. Aristotle says that finding this middle ground is essential to reaching eudemonia, the ultimate form of godlike consciousness. This middle ground is often referred to as The Golden Mean. Aristotle also wrote about his thoughts on the concept of justice in the Nicomachean Ethics. In these chapters, Aristotle defined justice in two parts, general justice and particular justice. General justice is Aristotle’s form of universal justice that can only exist in a perfect society. Particular justice is where punishment is given out for a particular crime or act of injustice. This is where Aristotle says an educated judge is needed to apply just decisions regarding any particular case. This is where we get the concept of he scales of justice, the blindfolded judge symbolizing blind justice, balancing the scales, weighing all the evidence and deliberating each particular case individually. Homonymy is an important theme in Aristotle’s justice because one form of justice can apply to one, while another would be best suited for a different person/case. Aristotle says that developing good habits can make a good human being and that practicing the use of The golden mean when applicable to virtues will allow a human being to live a healthy, happy life.

Aristotle's critics

Aristotle has been criticized on several grounds.

- His analysis of procreation is frequently criticized on the grounds that it presupposes an active, ensouling masculine element bringing life to an inert, passive, lumpen female element; it is on these grounds that some feminist critics refer to Aristotle as a misogynist.

- At times, the objections that Aristotle raises against the arguments of his own teacher, Plato, appear to rely on faulty interpretations of those arguments.

- Although Aristotle advised, against Plato, that knowledge of the world could only be obtained through experience, he frequently failed to take his own advice. Aristotle conducted projects of careful empirical investigation, but often drifted into abstract logical reasoning, with the result that his work was littered with conclusions that were not supported by empirical evidence: for example, his assertion that objects of different mass fall at different speeds under gravity, which was later refuted by John Philoponus (credit is often given to Galileo, even though Philoponus lived centuries earlier).

- In the Middle Ages, roughly from the 12th century to the 15th century, the philosophy of Aristotle became firmly established dogma. Although Aristotle himself was far from dogmatic in his approach to philosophical inquiry, two aspects of his philosophy might have assisted its transformation into dogma. His works were wide-ranging and systematic so that they could give the impression that no significant matter had been left unsettled. He was also much less inclined to employ the skeptical methods of his predecessors, Socrates and Plato.

- Some academics have suggested that Aristotle was unaware of much of the current science of his own time.

Aristotle was called not a great philosopher, but "The Philosopher" by Scholastic thinkers. These thinkers blended Aristotelian philosophy with Christianity, bringing the thought of Ancient Greece into the Middle Ages. It required a repudiation of some Aristotelian principles for the sciences and the arts to free themselves for the discovery of modern scientific laws and empirical methods.

The loss of his works

Although we know that Aristotle wrote many elegant treatises (Cicero described his literary style as "a river of gold"), the originals have been lost. All that we have now are the literary notes of his pupils, which are often difficult to read (the Nicomachean Ethics is a good example). It is now believed that we have about one fifth of his original works.

Aristotle underestimated the importance of his written work for humanity. He thus never published his books, only his dialogues. The story of the original manuscripts of his treatises is described by Strabo in his Geography and Plutarch in his "Parallel Lives, Sulla": The manuscripts were left from Aristotle to Theophrastus, from Theophrastus to Neleus of Scepsis, from Neleus to his heirs. Their descendants sold them to Apellicon of Teos. When Lucius Cornelius Sulla occupied Athens in 86 BCE, he carried off the library of Appellicon to Rome, where they were first published in 60 BCE from the grammarian Tyrranion of Amisus and then by philosopher Andronicus of Rhodes.

Bibliography

Note: Bekker numbers are often used to uniquely identify passages of Aristotle. They are identified below where available.

Major works

The extant works of Aristotle are broken down according to the five categories in the Corpus Aristotelicum. Not all of these are considered genuine, but differ with respect to their connection to Aristotle, his associates and his views. Some, such as the Athenaion Politeia or the fragments of other politeia are regarded by most scholars as products of Aristotle's "school" and compiled under his direction or supervision. Other works, such On Colours may have been products of Aristotle's successors at the Lyceum, e.g., Theophrastus and Straton. Still others acquired Aristotle's name through similarities in doctrine or content, such as the De Plantis, possibly by Nicolaus of Damascus. A final category, omitted here, includes medieval palmistries, astrological and magical texts whose connection to Aristotle is purely fanciful and self-promotional. Those that are seriously disputed are marked with an asterisk.

Logical writings

- Organon (collected works on logic):

- (1a) Categories (or Categoriae)

- (16a) On Interpretation (or De Interpretatione)

- (24a) Prior Analytics (or Analytica Priora)

- (71a) Posterior Analytics (or Analytica Posteriora)

- (100b) Topics (or Topica)

- (164a) On Sophistical Refutations (or De Sophisticis Elenchis)

Physical and scientific writings

- (184a) Physics (or Physica)

- (268a) On the Heavens (or De Caelo)

- (314a) On Generation and Corruption (or De Generatione et Corruptione)

- (338a) Meteorology (or Meteorologica)

- (391a) On the Cosmos (or De Mundo, or On the Universe) *

- (402a) On the Soul (or De Anima)

- (436a) Little Physical Treatises (or Parva Naturalia):

- On Sense and the Sensible (or De Sensu et Sensibilibus)

- On Memory and Reminiscence (or De Memoria et Reminiscentia)

- On Sleep and Sleeplessness (or De Somno et Vigilia)

- On Dreams (or De Insomniis) *

- On Prophesying by Dreams (or De Divinatione per Somnum)

- On Longevity and Shortness of Life (or De Longitudine et Brevitate Vitae)

- On Youth and Old Age (On Life and Death) (or De Juventute et Senectute, De Vita et Morte)

- On Breathing (or De Respiratione)

- (481a) On Breath (or De Spiritu) *

- (486a) History of Animals (or Historia Animalium, or On the History of Animals, or Description of Animals)

- (639a) On the Parts of Animals (or De Partibus Animalium)

- (698a) On the Gait of Animals (or De Motu Animalium, or On the Movement of Animals)

- (704a) On the Progression of Animals (or De Incessu Animalium)

- (715a) On the Generation of Animals (or De Generatione Animalium)

- (791a) On Colours (or De Coloribus) *

- (800a) De audibilibus

- (805a) Physiognomics (or Physiognomonica) *

- On Plants (or De Plantis) *

- (830a) On Marvellous Things Heard (or Mirabilibus Auscultationibus, or On Things Heard) *

- (847a) Mechanical Problems (or Mechanica) *

- (859a) Problems (or Problemata) *

- (968a) On Indivisible Lines (or De Lineis Insecabilibus) *

- (973a) Situations and Names of Winds (or Ventorum Situs) *

- (974a) On Melissus, Xenophanes and Gorgias (or MXG) * The section On Xenophanes starts at 977a13, the section On Gorgias starts at 979a11.

Metaphysical writings

- (980a) Metaphysics (or Metaphysica)

Ethical writings

- (1094a) Nicomachean Ethics (or Ethica Nicomachea, or The Ethics)

- (1181a) Great Ethics (or Magna Moralia) *

- (1214a) Eudemian Ethics (or Ethica Eudemia)

- (1249a) Virtues and Vices (or De Virtutibus et Vitiis Libellus, Libellus de virtutibus) *

- (1252a) Politics (or Politica)

- (1343a) Economics (or Oeconomica)

Aesthetic writings

- (1354a) Rhetoric (or Ars Rhetorica, or The Art of Rhetoric or Treatise on Rhetoric)

- Rhetoric to Alexander (or Rhetorica ad Alexandrum) *

- (1447a) Poetics (or Ars Poetica)

A work outside the Corpus Aristotelicum

- The Constitution of the Athenians (or Athenaion Politeia, or The Athenian Constitution)

Specific editions

- Princeton University Press: The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation (2 Volume Set; Bollingen Series, Vol. LXXI, No. 2), edited by Jonathan Barnes ISBN 0-691-09950-2 (The most complete recent translation of Aristotle's extant works)

- Oxford University Press: Clarendon Aristotle Series. Scholarly edition

- Harvard University Press: Loeb Classical Library (hardbound; publishes in Greek, with English translations on facing pages)

- Oxford Classical Texts (hardbound; Greek only)

Named after Aristotle

- Aristoteles, a crater on the Moon.

- The Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

- Aristotelous Square

Notes

link does not work

Further reading

The secondary literature on Aristotle is vast. The following references are only a small selection.

- Ackrill J. L. 2001. Essays on Plato and Aristotle, Oxford University Press, USA

- Adler, Mortimer J. (1978). Aristotle for Everybody. New York: Macmillan. A popular exposition for the general reader.

- Bakalis Nikolaos. 2005. Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments, Trafford Publishing ISBN 1-4120-4843-5

- Barnes J. 1995. The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle, Cambridge University Press

- Bocheński, I. M. (1951). Ancient Formal Logic. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

- Bolotin, David (1998). An Approach to Aristotle’s Physics: With Particular Attention to the Role of His Manner of Writing. Albany: SUNY Press. A contribution to our understanding of how to read Aristotle's scientific works.

- Burnyeat, M. F. et al. 1979. Notes on Book Zeta of Aristotle's Metaphysics. Oxford: Sub-faculty of Philosophy

- Chappell, V. 1973. Aristotle's Conception of Matter, Journal of Philosophy 70: 679-696

- Code, Alan. 1995. Potentiality in Aristotle's Science and Metaphysics, Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 76

- Frede, Michael. 1987. Essays in Ancient Philosophy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

- Gill, Mary Louise. 1989. Aristotle on Substance: The Paradox of Unity. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Guthrie, W. K. C. (1981). A History of Greek Philosophy, Vol. 6. Cambridge University Press.

- Irwin, T. H. 1988. Aristotle's First Principles. Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Lewis, Frank A. 1991. Substance and Predication in Aristotle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Loux, Michael J. 1991. Primary Ousia: An Essay on Aristotle's Metaphysics Ζ and Η. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

- Melchert, Norman (2002). The Great Conversation: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-19-517510-7.

- Owen, G. E. L. 1965c. The Platonism of Aristotle, Proceedings of the British Academy 50 125-150. Reprinted in In J. Barnes, M. Schofield, and R. R. K. Sorabji (eds.), Articles on Aristotle, Vol 1. Science. London: Duckworth (1975). 14-34

- Pangle, Lorraine Smith (2003). Aristotle and the Philosophy of Friendship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Aristotle's conception of the deepest human relationship viewed in the light of the history of philosophic thought on friendship.

- Reeve, C. D. C. 2000. Substantial Knowledge: Aristotle's Metaphysics. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Rose, Lynn E. (1968). Aristotle's Syllogistic. Springfield: Charles C Thomas Publisher.

- Ross, Sir David (1995). Aristotle, 6th ed.. London: Routledge. An classic overview by one of Aristotle's most prominent English translators, in print since 1923.

- Scaltsas, T. 1994. Substances and Universals in Aristotle's Metaphysics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Strauss, Leo. "On Aristotle's Politics" (1964), in The City and Man, Chicago; Rand McNally.

- Taylor, Henry Osborn (1922). “Chapter 3: Aristotle's Biology”, Greek Biology and Medicine.

- Veatch, Henry B. (1974). Aristotle: A Contemporary Appreciation. Bloomington: Indiana U. Press. For the general reader.

- Woods, M. J. 1991b. “Universals and Particular Forms in Aristotle's Metaphysics.” Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy supplement. 41-56

See also

- Aristotelian view of God

- Aristotelian theory of gravity

- Philia

- Phronesis

- Potentiality and actuality (Aristotle)

External links

- An extensive collection of Aristotle's philosophy and works, including lesser known texts

- Help with Aristotle essays

- Works by Aristotle at Project Gutenberg

- Template:PerseusAuthor

- Template:Planetmath

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

- "Biology" -- by James Lennox.

- "Causality" -- by Andrea Falcon.

- "Ethics" -- by Richard Kraut.

- "Logic" -- by Robin Smith.

- "Mathematics" -- by Henry Mendell.

- "Metaphysics" -- by S. Marc Cohen.

- "Philosophy of Nature" -- Istvan Bodnar.

- "Political Theory" -- by Fred Miller.

- "Psychology" -- by Christopher Shields.

- "Rhetoric" -- by Cristof Rapp.

- Aristotle OnLine Resources & Anthology of his works

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "Aristotle" — by William Turner.

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Aristotle".

- Aristotle section at EpistemeLinks

- A brief biography and e-texts presented one chapter at a time

- Aristotle and Indian logic

- Large collection of Aristotle's texts, presented page by page

- Source of most of the Biography and Methodology sections, as well as more overview

- Template:MacTutor Biography

- Test : Are you Aristotelian? (cf. Poetics)