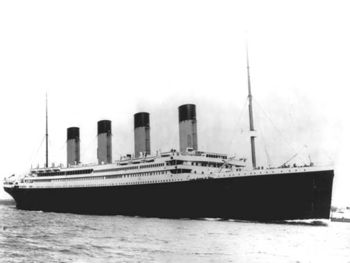

RMS Titanic

RMS[1] Titanic was a passenger liner that sank on its maiden voyage in April 1912 after it struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic Ocean. Although never officially named as "unsinkable", it was believed at the time that the Titanic's design would reduce the likelihood of such a disaster.

Titanic, along with its very similar sister ships Olympic and Britannic, was a British vessel built in Belfast at the Harland and Wolff shipyard for the White Star Line. It left Southhampton, England, on 10th April 1912, bound for New York via France and Ireland. After striking an iceberg late on 14th April, the ship sank in the early hours of the following day with the lost of 1,514 passengers and crew. Titanic had too few lifeboats for the more than 2,200 people on board, and many boats left with empty spaces due to a general failure to recognise the danger until it was too late.

The iceberg opened a gash in Titanic's starboard side, flooding compartments along the hull. The bow started to sink first; pressure further down the length of the ship led it to split towards the stern section. The remains of the ship lie in two main pieces two-and-a-half miles (four kilometres) below the surface.

The loss of the Titanic is the world's best known maritime disaster, and forced a rethink of ship design and other safety measures. The wreck was rediscovered in the 1980s and since then various artefacts have, sometimes controversially, been raised.

Construction

Sinking

Aftermath

Rediscovery

Legacy

The Titanic disaster has proven to be fertile ground for the imaginations of everyone from film producers to conspiracy theorists.

Film

There have been several films abut Titanic, ranging from a 1943 Nazi propaganda exercise, to the acclaimed A Night to Remember and the 1997 big-budget take on the tragedy, directed by James Cameron. The 1997 film was the first major production to depict the vessel splitting into two pieces as it sank; previous productions had not shown this because the British and American inquiries into the disaster recorded that the ship had gone down intact, despite some eyewitness accounts to the contrary, and this erroneous version of events persisted for decades.[2]

Conspiracy theories and other claims

Perhaps the most persistent conspiracy theory surrounding the Titanic tragedy is the idea that the ship was deliberately sunk as part of an insurance scam. This is sometimes referred to as the 'Titanic switch' because it also includes the claim that the name of the Titanic was swapped with that of its sister ship Olympic, and that therefore the 'real' Titanic sailed on for over 20 years of safe and reliable service while Olympic rested at the bottom of the Atlantic. Proponents of this view allege that, following a well-documented collision involving the Olympic a few years earlier, the owners of the vessels discovered that the Titanic's sister ship was far more damaged than publicly disclosed. Fearing that insurers would refuse to pay out, they opted to rename the ship, scuttle it, make this look like an accident and collect the insurance money. Evidence for any of this is limited and would have required the owners to recklessly endanger many people. The plot also stretches credulity since it would presumably have involved a great many people to be involved to have carried out and covered up the switch, who then all took the secret to their graves. Finally, analysis of the wreck itself has for most commentators put the theory to rest.

Various other claims about the sinking have popped up over the years, including an idea that a serious fire actually sank the vessel rather than the iceberg; the belief that an Ancient Egyptian mummy being transported onboard took the ship down with it as part of a curse; and the speculation that perhaps Titanic was sunk by the extra weight of time machines piloted by interested observers from the future materialising inside it.[3]

Footnotes

- ↑ Royal Mail Ship; the Titanic carried mail as well as passengers and other cargo.

- ↑ Titanic Inquiry: 'United States Senate Inquiry - Ship Sinking' and 'British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry', 1912.

- ↑ Randles, J. (1994). Time Travel: Fact, Fiction and Possibility.