Kanji

- See also: Chinese characters

Kanji (漢字, literally 'Chinese characters') are Chinese-derived characters used to write some elements of the Japanese language; some of them were invented in Japan or Korea, so are not Chinese in origin. Kanji are also not used in exactly the same way as traditional or simplified Chinese characters used to write modern Mandarin or other varieties of Chinese,[1] though many characters do have similar or the same meanings. This means that, to some degree, literate readers of Chinese or Japanese can recognise meanings in the other language, though this depends very much on the complexity of the text. These characters are the world's oldest writing system in that they have the longest record of continuous use, dating back thousands of years. Characters can be written vertically, in columns from right to left, but it is increasingly common to see them written horizontally, left to right (newspapers take advantage of this to display articles both vertically and horizontally on the same page).

Kanji have a long history in Japan, emerging perhaps by the fifth century CE, but initially their use was restricted to the work of highly literate elites who brought the characters from China, often via Korea. Other writing systems with symbols based on simplified kanji also later emerged, and widespread use of kanji therefore occurred relatively late in Japanese history. More kanji were invented in Japan and Korea. Today, there are 2,136 'official' kanji (常用漢字 jooyoo kanji) sanctioned by the Japanese government for learning in schools, and another 861 official characters mainly used in people's names (人名用漢字 jinmeeyoo kanji), but there are also many others that are outside these lists.

Classification

A few characters, such as 山 'mountain', somewhat resemble that which they represent, but only a small number of characters are like this and it usually difficult to recognise the meaning. Most characters are completely abstract, or what they mean is only obvious with hindsight: 馬,[2] for example. A minority of characters, particularly some of the more frequent ones, represent words without indicating pronunciation at all (i.e. they are logographic): for example, 日 means 'sun', and its native Japanese pronunciation is hi. However, the vast majority of characters include a pronunciation element, which can give a (rough) idea of the Chinese-derived pronunciation of the character.

A linguistic approach might identify characters in their Chinese pronunciation as 'morphosyllabic' - morphemic, in that they represent basic units of meaning (morphemes), and syllabic, in that most characters represent a single syllable, an abstract unit of phonology.[3] Characters do not, therefore, represent 'thoughts on paper' divorced from language, and cannot be easily co-opted to write any language; for Japanese, other symbols were necessary to represent grammatical structures not found in Chinese varieties (see Kana below).

Pronunciation in Japanese

Early kanji were borrowed alongside large numbers of Chinese words, so most kanji have at least two 'readings' (ways to pronounce the character). One is derived from the Chinese lexicon (音読み on'yomi) - often from up to about 1,500 years ago, and filtered through Japanese phonology - while the other is a native Japanese reading (訓読み kun'yomi). As Chinese and Japanese are unrelated in syntactic, phonological and other grammatical terms, these two readings are very different. For example, the character 口 'mouth' can be read as KOO[4] in the Chinese reading and as kuchi in the Japanese reading. Often, the Chinese reading is used in compounds such as 人口 (jinkoo 'population') while the Japanese form is used when the character stands alone. Chinese readings are common for nouns as well, while verbs often use the Japanese reading: for example, 寝 in 就寝する shuushin suru 'retire [to bed]' uses the Chinese reading SHIN in the noun shuushin 'retiring', but in the more common verb 寝る neru 'to lie down [go to sleep]', the Japanese reading ne occurs.

Kanji and Kana

| Sample text:

時間と勇気がある旅行者にとって、カリフォルニアの海岸線はドラマティックな景色と歴史と多様な文化が交鎖する魅惑的なドライビングロードといえる。 Jikan to yuuki ga aru ryokoosha ni totte, Kariforunia no kaigansen wa doramatikku na keshiki to rekishi to tayoo na bunka ga koosa suru miwaku teki na doraibingu roodo to ieru. 'For travellers who have the time and courage, the coastline roads of California, where dramatic sceneries, history and different cultures intersect, can be fascinating to drive.'

|

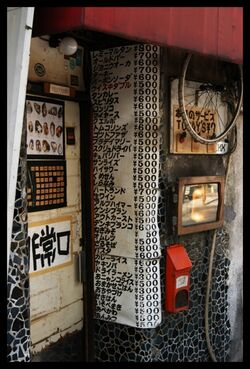

Photo © by Sonny Santos, used by permission.

Japanese also makes use of fewer characters than Chinese, so many characters have multiple readings. In modern Japanese, new words borrowed from other languages are not written in kanji but phonologically in カタカナ katakana, a script which represents the moras of Japanese (units similar to syllables). Other words, particularly grammatical particles, are written in another mora-based script, ひらがな hiragana. In the past, these scripts were more widely used,[5] and so today there are many words in Japanese that have no kanji assigned to them, or for which the characters are little-used: 熊 kuma 'bear' is more often written in hiragana or katakana as くま or クマ, for example, although it has recently been re-introduced into the jooyoo kanji list of characters that are taught in primary and secondary schools. Both scripts developed through simplification of Chinese characters and elimination of their meaningful components, so that kana would become phonological alone.

In the sample to the left, from Yamaguchi (2007: 78-79), the simpler and more angular symbols are katakana and are here used, as is typical, to render words such as Kariforunia 'California' and doraibingu 'driving', i.e. foreign names plus relatively recent loanwords. The symbols which have generally simpler strokes than the kanji but are more curved than the katakana are hiragana, and here often serve to represent grammatical particles such as the subject marker が ga.

Kanji-kana alternation

While some Japanese words simply have no kanji assigned to them, others can be written using a kanji but rarely are. Sometimes this is a consequence of the kanji being difficult to write: the common word kirei 'pretty' or 'clean', for example, is rarely represented as 綺麗 (or 綺麗, an alternative), though the use of computers has led to some previously-obsolete kanji such as these being reintroduced.[6] In other cases, kanji and kana may alternate according to the way the words are used. For example, a writer may mark their opinion with kana and reserve the kanji for a real quotation (see box, left). In the example discussed in Yamaguchi (2007: 78-79), the final word, いえる ieru, literally means 'can be said', and would be ambiguous as to whether someone has actually said that the roads are interesting or whether this is the writer's opinion. Ieru written as 言える, with a kanji used for the semantic element, would indicate an actual quotation.[7] Thus kanji and kana may disambiguate language that can otherwise be hard to interpret.[8]

Footnotes

- ↑ Hànzì (simplified Chinese 汉字; traditional Chinese: 漢字).

- ↑ 'Horse'. The lower strokes were once the legs.

- ↑ DeFrancis (1984: 187).

- ↑ Chinese readings are capitalised in roomaji for ease of distinction.

- ↑ Gottlieb (2005: 130).

- ↑ Gottlieb (2005: 130-131).

- ↑ This discussion summarises Yamaguchi's comments.

- ↑ Another example, from the beginning of the sample text, is とって totte. When used with the grammatical particle に ni, this verb form means roughly 'according to' or [as far as someone] is concerned'. However, as 取って, totte represents a form of the full, meaningful verb 'take', with its base form 取る toru.