California, history to 1845

This article covers in brief the history of California until the year 1899; for later events, see History of California 1900 to present. For additional information and more notes and citations, see the Main article links at the top of most sections.

The article tells the story of California from the time that immigrants from Asia began arriving some 13,000 years ago, and perhaps earlier. It tells of the exploration of the coasts and inland valleys by European explorers, the rapid influx of fortune-hunters and adventurers beginning with the California Gold Rush in the 1850s, and ends in 1899 with a largely agricultural and rural California with a population of some 1.4 million people.

Before European contact

The circumstances of the arrival of the first humans in California remain a mystery. In all, some 30 tribes (or culture groups) lived in the area of present-day California, gathered into perhaps six different language family groups. These groups included the early-arriving Hokan family (winding up in the mountainous far north and Colorado River basin in the south), and the recently arrived Uto-Aztekan of the desert southeast. This cultural diversity was among the densest in North America, and was likely the result of a series of migrations and invasions during the last 10,000-15,000 years.[1]

While the general consensus is that California was populated by groups of humans coming over the Bering Strait from Asia, the details of these groups’ passage and arrival are unknown. The remains of Arlington Springs Man on Santa Rosa Island are among the traces of a very early habitation, dated to the last ice age (Wisconsin glaciation) about 13,000 years ago. At the time of the first European contact, Native American tribes included the Chumash, Maidu, Miwok, Modoc, Mohave, Ohlone, Shasta, and Tongva.

Tribes adapted to California’s many climates. Coastal tribes were a major source of trading beads, produced from mussel shells using stone tools. Tribes in California's broad Central Valley and the surrounding foothills developed an early agriculture, burning the grasslands to encourage growth of edible wild plants, especially oak trees. The acorns from these trees were pounded into a powder, and the acidic tannin leached out to make edible flour. Tribes living in the mountains of the north and east relied heavily on salmon and game hunting, and used California’s volcanic legacy by collecting and shaping obsidian for themselves and for trade. The deserts of the southeast were home to tribes who learned to thrive in that harsh environment, by making careful use of local plants and living in oases and along water courses.

The status of all these people remained dynamic, as the more successful tribes expanded their territories, and less successful tribes contracted. Slave-trading and war among tribes alternated with periods of relative peace. In all, it is estimated by the time of extensive European contact in the 1700s, that perhaps 300,000 Native Americans were living within what is now California.

European exploration (1530 – 1765)

The first European explorers, flying the flags of Spain and of England, sailed along the coast of California from the early 1500s to the mid-1700s, but no European settlements were established. The most important colonial power, Spain, focused attention on its imperial centers in Mexico, Peru, and the Philippines. Confident of Spanish claims to all lands touching the Pacific Ocean (including California), Spain simply sent an occasional exploring party sailing along the California coast. The California seen by these ship-bound explorers was one of hilly grasslands and forests, with few apparent resources or natural ports to attract colonists.

The other colonial states of the era, with their interest on more densely populated areas, paid limited attention to this distant part of the world. It was not until the middle of the 1700s, that both Russian and British explorers and fur-traders began encroaching on the margins of the area.

Hernán Cortés

About 1530, Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán (President of New Spain) was told by an Indian slave of the Seven Cities of Cibola that had streets paved with gold and silver. About the same time, Hernán Cortés was attracted by stories of a wonderful country far to the northwest, populated by Amazonish women and abounding with gold, pearls, and gems. The Spaniards conjectured that these places may be one and the same.

An expedition in 1533 discovered a bay, most likely that of La Paz, before experiencing difficulties and returning. Cortés accompanied expeditions in 1534 and 1535 without finding the sought-after city.

On May 3, 1535, Cortés claimed "Santa Cruz Island" (now known as the peninsula of Baja California), and laid out and founded the city that was to become LaPaz later that spring.

Francisco de Ulloa

Also: Island of California

In July 1539, moved by the renewal of those stories, Cortés sent Francisco de Ulloa out with three small vessels. He made it to the mouth of the Colorado, then sailed around the peninsula as far as Cedros Island.

The account of this voyage marks the first recorded application of the name "California". It can be traced to the fifth volume of a chivalric romance, Amadis de Gallia, arranged by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo and first printed around 1510, in which a character travels through an island called "California".

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

The first European to explore the coast was Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, a Portuguese navigator sailing for the Spanish Crown. In June, 1542 Cabrillo led an expedition in two ships from the west coast of what is now Mexico. He landed on September 28 at San Diego Bay, claiming what he thought was the Island of California for Spain.

Cabrillo and his crew landed on San Miguel, one of the Channel Islands, then continued north in an attempt to discover a supposed coastal route to the mainland of Asia. Cabrillo likely sailed as far north as Pt. Reyes (north of San Francisco), but died as the result of an accident during this voyage; the remainder of the expedition, which likely reached as far north as the Rogue River in today's southern Oregon was led by Bartolomé Ferrelo.[2]

Sir Francis Drake

On June 7 1579, the English explorer Sir Francis Drake saw an excellent port, which he called Nova Albion and claimed for England. The location remains unknown and there was no follow-up.[3]

Sebastián Vizcaíno

In 1602, the Spaniard Sebastián Vizcaíno explored California's coastline as far north as Monterey Bay, where he put ashore. He ventured inland south along the coast, and recorded a visit to what is likely Carmel Bay. His major contributions to the state's history were the glowing reports of the Monterey area as an anchorage and as land suitable for settlement, as well as the detailed charts he made of the coastal waters (which were used for nearly 200 years).[4]

European exploration (1765 – 1821)

British seafaring Captain James Cook, midway through his third and final voyage of exploration in 1778, sailed along the west coast of North America aboard the HMS Resolution, mapping the coast from California all the way to the Bering Strait. In 1786 Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse, led a group of scientists and artists on a voyage of exploration ordered by Louis XVI and were welcomed in Monterey. They compiled an account of the Californian mission system, the land and the people. Traders, whalers and scientific missions followed in the next decades.[5]

Spanish colonization and governance (1697 – 1821)

In 1697 the Jesuit missionary Juan María de Salvatierra established Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó, the first permanent mission in Baja California Sur. The California territory at this time was part of New Spain, and not divided as it is today. Jesuit control over the peninsula was gradually extended, first in the region around Loreto, then to the south in the Cape region, and finally toward the north across the northern boundary of Baja California Sur. By 1765, 21 missions were established in California.

During the last quarter of the 18th century, the first Spanish settlements were established in Alta California. Reacting to interest by Russia and possibly Great Britain in the fur-bearing animals of the Pacific north coast, Spain further extended the series of Catholic missions, accompanied by troops and establishing ranches, along the southern and central coast of California. These missions were intended to demonstrate the claim of the Spanish Empire to modern-day California.

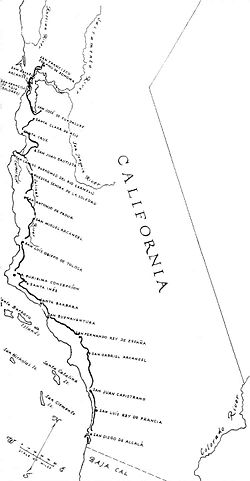

The first quarter of the 19th century continued the slow colonization of the southern and central California coast by Spanish missionaries, ranchers, and troops. By 1820, Spanish influence was marked by the chain of missions reaching from Loreto, north to San Diego to just north of today's San Francisco Bay area, and extended inland approximately 25 to 50 miles from the missions. Outside of this zone, perhaps 200,000 to 250,000 Native Americans were continuing to lead traditional lives. The Adams-Onís Treaty, signed in 1819 set the northern boundary of the Spanish claims at the 42nd parallel, effectively creating today's northern boundary between California and Oregon.

First Spanish colonies

Spain had maintained a number of missions and presidios throughout New Spain since 1493. The Crown laid claim to the north costal provinces of California since 1542. Excluding Santa Fe in New Mexico, it was slow in settlement for 155 years. Although establishments officially beginning in Loreto, Baja California Sur were established in 1697, It wasn't until the threat of an incursion by Russia, coming down from Alaska in 1765, that King Charles III of Spain felt development of more northern installations were necessary. By then the Spanish Empire was engaged in the political aftermath of the Seven Years' War and colonial priorities in far away California afforded only a minimal effort. Alta California was to be settled by Franciscan monks, protected by troops in the California Missions. Between 1774 and 1791, the Crown sent forth a number of expeditions to further explore and settle Alta California and the Pacific Northwest.

Gaspar de Portolà

In May 1768, the Spanish Visitor General, José de Gálvez, planned a four-prong expedition to settle Alta California, two by sea and two by land, which Gaspar de Portolà volunteered to command.

The Portolà land expedition arrived at the site of present-day San Diego on June 29, 1769, where it established the Presidio of San Diego. Eager to press on to Monterey Bay, de Portolà and his group, consisting of Father Juan Crespi, sixty-three leather-jacket soldiers and a hundred mules, headed north on July 14. They moved quickly, reaching the present-day sites of Los Angeles on August 2, Santa Monica on August 3, Santa Barbara on August 19, San Simeon on September 13 and the mouth of the Salinas River on October 1. Although they were looking for Monterey Bay, the group failed to recognize it when they reached it.

On October 31, de Portolà's explorers became the first Europeans known to view San Francisco Bay. Ironically, the Manila Galleons had sailed along this coast for almost 200 years by then. The group returned to San Diego in 1770.

Junípero Serra

Junípero Serra was a Majorcan (Spain) Franciscan who founded the Alta California mission chain. After King Carlos III ordered the Jesuits expelled from "New Spain" on February 3, 1768, Serra was named "Father Presidente."

Serra founded San Diego de Alcalá in 1769. Later that year, Serra, Governor de Portolà and a small group of men moved north, up the Pacific Coast. They reached Monterey in 1770, where Serra founded the second Alta California mission, San Carlos Borromeo.

Alta California missions

The California Missions comprise a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholic Dominicans, Jesuits, and Franciscans, to spread the Christian doctrine among the local Native Americans, but with the added benefit of confirming historic Spanish claims to the area. The missions introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and industry into the California region.

Most missions were small, with normally two Franciscans and six to eight soldiers in residence. All of these buildings were built largely with unpaid native labor under Franciscan supervision. In addition to the presidio (royal fort) and pueblo (town), the misión was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown in an attempt to consolidate its colonial territories. None of these missions were completely self-supporting, requiring continued (albeit modest) financial support. Starting with the onset of the Mexican War of Independence in 1810, this support largely disappeared and the missions and their converts were left on their own.

In order to facilitate overland travel, the mission settlements were situated approximately 30 miles (48 kilometers) apart, so that they were separated by one day's long ride on horseback along the 600-mile (966-kilometer) long El Camino Real (Spanish for "The Royal Highway," though often referred to as "The King's Highway"), and also known as the California Mission Trail. Heavy freight movement was practical only via water. Tradition has it that the padres sprinkled mustard seeds along the trail in order to mark it with bright yellow flowers.

Four presidios, strategically placed along the California coast and organized into separate military districts, served to protect the missions and other Spanish settlements in Upper California.

A number of mission structures survive today or have been rebuilt, and many have congregations established since the beginning of the 20th century. The highway and missions have become for many a romantic symbol of an idyllic and peaceful past. The "Mission Revival Style" was an architectural movement that drew its inspiration from this idealized view of California's past.

Ranchos

The Spanish (and later the Mexicans) encouraged settlement with large land grants which were turned into ranchos, where cattle and sheep were raised. Cow hides (at roughly $1 each) and fat (known as tallow, used to make candles as well as soaps) were the primary exports of California until the mid-19th century. The owners of these ranchos styled themselves after the landed gentry in Spain. Their workers included some Native Americans who had learned to speak Spanish and ride horses.Template:Facts

Russian attempts at colonization

Beginning in the early 1800s, fur trappers of the Russian Empire explored the West Coast, hunting for sea otter pelts as far south as San Diego. In August of 1812 the Russian-American Company set up a fortified trading post at Fort Ross, near present day Bodega Bay on the Sonoma Coast sixty miles north of San Francisco on land claimed, but not occupied by, Great Britain. This colony was active until 1841. El Presidio de Sonoma, or Sonoma Barracks, was established in 1836 by Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (the "Commandante-General of the Northern Frontier of Alta California") as a part of Mexico's strategy to halt Russian incursions into the region.

Mexican era (1821-1846)

General

Substantial changes occurred during the second quarter of the 19th century. Mexican independence from Spain in 1821 marked the end of European rule in California; the missions faded in importance under Mexican control while ranching and trade increased. By the mid-1840s, the increased presence of Americans made the northern part of the state diverge from southern California, where the Spanish-speaking "Californios" dominated.

By 1846, California had a Spanish-speaking population of under 10,000, tiny even compared to the sparse population of states in Mexico proper. The "Californios," as they were known, consisted of about 800 families, mostly concentrated on a few large ranchos. About 1,300 Americans and a very mixed group of about 500 Europeans, scattered mostly from Monterey to Sacramento dominated trading as the Californios dominated ranching. In terms of adult males, the two groups were about equal, but the Americans were more recent arrivals.

Secularization

The Mexican Congress passed An Act for the Secularization of the Missions of California on August 17, 1833. Mission San Juan Capistrano was the very first to feel the effects of this legislation the following year. The Franciscans soon thereafter abandoned the missions, taking with them most everything of value, after which the locals typically plundered the mission buildings for construction materials.

Other nationalities

- In this period, American and British trappers began entering California in search of beaver. Using the Siskiyou Trail, Old Spanish Trail, and later, the California Trail, these trapping parties arrived in California, often without the knowledge or approval of the Mexican authorities, and laid the foundation for the arrival of later Gold Rush era Forty-Niners, farmers and ranchers.

- In 1840, the American adventurer, writer and lawyer Richard Henry Dana wrote of his experiences aboard ship off California in the 1830s in "Two Years Before the Mast" (etext [2])

- The leader of a French scientific expedition to California, Eugene Duflot de Mofras, wrote in 1840 "...it is evident that California will belong to whatever nation chooses to send there a man-of-war and two hundred men."[6] In 1841, General Vallejo wrote Governor Alvarado that "...there is no doubt that France is intriguing to become mistress of California," but a series of troubled French governments did not uphold French interests in the area. During disagreements with Mexicans, the German-Swiss Francophile John Sutter threatened to raise the French flag over California and place himself and his settlement, New Helvetia, under French protection.

American interest and immigrants

Although a small number of American traders and trappers had lived in California since the early 1830s, the first organized overland party of American immigrants was the Bidwell-Bartleson party of 1841. With mules and on foot, this pioneering group groped their way across the continent using the still untested California Trail.[7] Also in 1841, an overland exploratory party of the United States Exploring Expedition came down the Siskiyou Trail from the Pacific Northwest. In 1844, Caleb Greenwood guided the first settlers to take wagons over the Sierra Nevada. In 1846, the misfortunes of the Donner Party earned notoriety as they struggled to enter California.

By 1846, the province had a non-Native American population of about 1500 Californio adult men (with about 6500 women and children), who lived mostly in the southern half. About 2,000 recent immigrants (almost all adult men) lived mostly in the northern half of California.

United States era (beginning 1846)

Bear Flag Revolt and American conquest

When war was declared on May 13, 1846 between the United States and Mexico, it took almost two months (mid-July 1846) for definite word of war to get to California. U.S. consul Thomas O. Larkin, stationed in Monterey, on hearing rumors of war tried to keep peace between the Americans and the small Mexican military garrison commanded by José Castro. American army captain John C. Frémont with about 60 well-armed men had entered California in December 1845 and was making a slow march to Oregon when they received word that war between Mexico and the U.S. was imminent. [3]

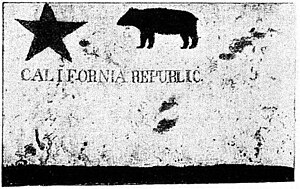

On June 15, 1846, some 30 non-Mexican settlers, mostly Americans, staged a revolt and seized the small Mexican garrison in Sonoma. They raised the "Bear Flag" of the California Republic over Sonoma. It lasted one week until the U.S. Army, led by Fremont, took over on June 23. The California state flag today is based on this original Bear Flag, and continues to contain the words "California Republic."

Commodore John Drake Sloat, on hearing of imminent war and the revolt in Sonoma, ordered his naval forces to occupy Yerba Buena (present San Francisco) on July 7 and raise the American flag. On July 15, Sloat transferred his command to Commodore Robert F. Stockton, a much more aggressive leader. Commodore Stockton put Frémont's forces under his orders. On July 19th, Frémont's "California Battalion" swelled to about 160 additional men from newly arrived settlers near Sacramento, and he entered Monterey in a joint operation with some of Stockton's sailors and marines. The official word had been received -- the Mexican-American War was on. The American forces easily took over the north of California; within days they controlled San Francisco, Sonoma, and Sutter's Fort in Sacramento.

In Southern California, Mexican General José Castro and Governor Pío Pico fled from Los Angeles. When Stockton's forces entered Los Angeles unresisted on August 13, 1846, the nearly bloodless conquest of California seemed complete. Stockton, however, left too small a force (36 men) in Los Angeles, and the Californios, acting on their own and without help from Mexico, led by José Mariá Flores , forced the small American garrison to retire in late September. 200 Reinforcements sent by Stockton, led by US Navy Capt William Mervine were repulsed in the Battle of Dominguez Rancho October 7 through October 9, 1846, near San Pedro, where 14 US Marines were killed. Meanwhile, General Kearny with a much reduced squadron of 100 dragoons finally reached California after a grueling march across New Mexico, Arizona and the Sonora desert. On December 6, 1846, They fought the Battle of San Pasqual near San Diego, California, where 18 of Kearny's troop were killed--the largest American casualties lost in battle in California.

Stockton rescued Kearny's surrounded forces and with their combined force, they moved northward from San Diego, entering the Los Angeles area on January 8, 1847, linking up with Frémont's men and with American forces totaling 660 troops, they fought the Californios in the Battle of Rio San Gabriel and the next day, on January 9, 1847, they fought the Battle of La Mesa. Three days later, on January 12, 1847, the last significant body of Californios surrendered to American forces. That marked the end of the War in California. On January 13, 1847, the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed.

On January 28, 1847, Army lieutenant William Tecumseh Sherman and his army unit arrived in Monterey, California as American forces in the pipeline continued to stream into California. On March 15, 1847, Col. Jonathan D. Stevenson’s Seventh Regiment of New York Volunteers of about 900 men start arriving in California. All of these men were in place when gold was discovered in January 1848.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2 1848, marked the end of the Mexican-American War. In that treaty, the United States agreed to pay Mexico $18,250,000; Mexico formally ceded California (and other northern territories) to the United States, and a new international boundary was drawn; San Diego Bay is one of the only natural harbors in California south of San Francisco, and to claim all this strategic water, the border was slanted to include it.

Gold Rush

In January 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill in the Sierra Nevada foothills about 40 miles east of Sacramento — beginning the California Gold Rush, which had the most extensive impact on population growth of the state of any era [4] [5].

The miners and merchants settled in towns along what is now State Highway 49, and settlements sprang up along the Siskiyou Trail as gold was discovered elsewhere in California (notably in Siskiyou County). The nearest deep-water seaport was San Francisco Bay, and San Francisco became the home for bankers who financed exploration for gold.

The Gold Rush brought the world to California. By 1855, some 300,000 "Forty-Niners" had arrived from every continent; many soon left, of course--some rich, most not very rich. A precipitous drop in the Native American population occurred in the decade after the discovery of gold.

Statehood: 1849-1850

In 1847-49 California was run by the U.S. military; local government continued to be run by alcaldes (mayors) in most places; but now some were Americans. Bennett Riley, the last military governor, called a constitutional convention to meet in Monterey in September 1849. Its 48 delegates were mostly pre-1846 American settlers; 8 were Californios. They unanimously outlawed slavery and set up a state government that operated for 10 months before California was given official statehood by Congress on September 9, 1850 as part of the Compromise of 1850. [8] A series of small towns were used briefly as the state capital until finally Sacramento was selected in 1854.

The Civil War

Because of the distance factor, California played a minor role in the American Civil War. Although some settlers sympathized with the Confederacy, they were not allowed to organize and their newspapers were closed down. Former Senator William Gwin, a Confederate sympathizer, was arrested and fled to Europe. Powerful capitalists dominated in Californian politics through their control of mines, shipping, and finance controlled the state through the new Republican party. Nearly all the men who volunteered as soldiers stayed in the West to guard facilities. Some 2,350 men in the California Column marched east across Arizona in 1862 to expel the Confederates from Arizona and New Mexico. The California Column spent most of its energy fighting hostile Indians.

Labor politics and the rise of Nativism

After the Civil War ended in 1865, California continued to grow rapidly. Independent miners were largely displaced by large corporate mining operations. Railroads began to be built, and both the railroad companies and the mining companies began to hire large numbers of laborers. The decisive event was the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869; six days by train brought a traveller from Chicago to San Francisco, compared to six months by ship. Thousands of Chinese men arrived, lured by high cash wages. They were expelled from the mine fields. Most returned to China after the Central Pacific was built. Those who stayed mostly moved to the Chinatown in San Francisco and a few other cities, where they were relatively safe from violent attacks they suffered elsewhere.

From 1850 through 1900, anti-Chinese nativist sentiment resulted in the passage of innumerable laws, many of which remained in effect well into the middle of the 20th century. The most flagrant episode was probably the creation and ratification of a new state constitution in 1879. Thanks to vigorous lobbying by the anti-Chinese Workingmen's Party, led by Dennis Kearney (an immigrant from Ireland), Article XIX, section 4 forbade corporations from hiring Chinese coolies, and empowered all California cities and counties to completely expel Chinese persons or to limit where they could reside. It was repealed in 1952.

The 1879 constitutional convention also dispatched a message to Congress pleading for strong immigration restrictions, which led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The Act was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1889, and it would not be repealed by Congress until 1943. Similar sentiments led to the development of a Gentlemen's Agreement with Japan, by which Japan voluntarily agreed to restrict emigration to the United States. California also passed an Alien Land Act which barred aliens, especially Asians, from holding title to land. Because it was difficult for people born in Asia to obtain U.S. citizenship until the 1960s, land ownership titles were held by their American-born children, who were full citizens. The law was overturned by the California Supreme Court as unconstitutional in 1952.

In 1886, when a Chinese laundry owner challenged the constitutionality of a San Francisco ordinance clearly designed to drive Chinese laundries out of business, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in his favor, and in doing so, laid the theoretical foundation for modern equal protection constitutional law. See Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886). Meanwhile, even with severe restrictions on Asian immigration, tensions between unskilled workers and wealthy landowners persisted up to and through the Great Depression. Novelist Jack London writes of the struggles of workers in the city of Oakland in his visionary classic, Valley of the Moon, a title evoking the pristine situation of Sonoma County between sea and mountains, Redwoods and Oaks, fog and sunshine.

Rise of the railroads

The establishment of America's transcontinental rail lines permanently linked California to the rest of the country, and the far-reaching transportation systems that grew out of them during the century that followed contributed immeasurably to the state’s unrivaled social, political, and economic development.

Notes

- ↑ Before California: An archaeologist looks at our earliest inhabitants [1] See Map of California Tribes.

- ↑ U.S. National Park Service official website about Juan Cabrillo. (retrieved 2006-12-18)

- ↑ The 1936 Drake's Plate of Brass was a hoax.

- ↑ Information from Monterey County Museum about Vizcaino's voyage and Monterey landing (retrieved 2006-12-18); Summary of Vizcaino expedition diary (retrieved 2006-12-18]

- ↑ The French In Early California. Ancestry Magazine. Retrieved on March 24, 2006.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1884-1890) History of California, v.4, The works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, complete text online, p.260

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1884-1890) History of California, v.4, The works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, complete text online, p.263-273.

- ↑ Richard B. Rice et al, The Elusive Eden (1988) 191-95

References

Surveys

- Hubert Howe Bancroft. The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, vol 18-24, History of California to 1890; complete text online; written in the 1880s, this is the most detailed history,

- Robert W. Cherny, Richard Griswold del Castillo, and Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo. Competing Visions: A History of California (2005), new textbook

- Gutierrez, Ramon A. and Richard J. Orsi (ed.) Contested Eden: California before the Gold Rush (1998), essays by scholars

- Carolyn Merchant, ed. Green Versus Gold: Sources In California's Environmental History (1998) readings in primary and secondary sources

- Rawls, James and Walton Bean (2003). California: An Interpretive History. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. ISBN 0-07-052411-4. 8th edition of standard textbook

- Rice, Richard B., William A. Bullough, and Richard J. Orsi. Elusive Eden: A New History of California 3rd ed (2001), standard textbook

- Rolle, Andrew F. . California: A History 6th ed. (2003), standard textbook

- Starr, Kevin California: A History (2005), interpretive history

- Sucheng, Chan, and Spencer C. Olin, eds. Major Problems in California History (1996), primary and secondary documents

to 1846

- Beebe (ed.), Rose Marie; Senkewicz, Robert M. (ed.) (2001). Lands of promise and despair; chronicles of early California, 1535-1846. Santa Clara, Calif.: Santa Clara University. , primary sources

- Camphouse, M. (1974). Guidebook to the Missions of California. Anderson, Ritchie & Simon, Los Angeles, CA. ISBN 0-378-03792-7.

- Chartkoff, Joseph L.; Chartkoff, Kerry Kona (1984). The archaeology of California. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Charles E. Chapman; A History of California: The Spanish Period Macmillan, 1991

- Dillon, Richard (1975). Siskiyou Trail. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Fagan, Brian (2003). Before California: An archaeologist looks at our earliest inhabitants. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Heizer, Robert F. (1974). The destruction of California Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Albert L. Hurtado, John Sutter: A Life on the North American Frontier (2006) University of Oklahoma Press, 416 pp. ISBN 0-8061-3772-X.

- Johnson, P., ed. (1964). The California Missions. Lane Book Company, Menlo Park, CA.

- McLean, James (2000). California Sabers. Indiana University Press.

- Kent Lightfoot. Indians, Missionaries, and Merchants: The Legacy of Colonial Encounters on the California Frontiers (2004)

- Moorhead, Max L. (1991). The Presidio: Bastion Of The Spanish Borderlands. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK. ISBN 0-8061-2317-6.

- Moratto, Michael J.; Fredrickson, David A. (1984). California archaeology. Orlando: Academic Press.

- Utley, Robert M. (1997). A life wild and perilous; mountain men and the paths to the Pacific. New York: Henry Holt and Co..

- Wright, R. (1950). California's Missions. Hubert A. and Martha H. Lowman, Arroyo Grande, CA.

- Young, S., and Levick, M. (1988). The Missions of California. Chronicle Books LLC, San Francisco, CA. ISBN 0-8118-1938-8.

1846-1900

- Brands, H.W. The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream (2003)

- Burchell, Robert A. "The Loss of a Reputation; or, The Image of California in Britain before 1875," California Historical Quarterly 53 (Summer I974): 115-30, stories about Gold Rush lawlessness slowed immigration for two decades

- Burns, John F. and Richard J. Orsi, eds; Taming the Elephant: Politics, Government, and Law in Pioneer California University of California Press, 2003

- Drager, K., and Fracchia, C. (1997). The Golden Dream: California from Gold Rush to Statehood. Graphic Arts Center Publishing Company, Portland, OR. ISBN 1-55868-312-7.

- Hunt, Aurora (1951). Army of the Pacific. Arthur Clark Company.

- Jelinek, Lawrence. Harvest Empire: A History of California Agriculture (1982) (ISBN 0-87835-131-0)

- McAfee, Ward. California's Railroad Era, 1850-1911 (1973)

- Olin, Spencer. California Politics, 1846-1920 (1981)

- Pitt, Leonard. The Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846-1890 (1966) (ISBN 0-520-01637-8)

- Saxton, Alexander. The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California (1971) (ISBN 0-520-02905-4)

- Starr, Kevin. Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (1986)

- Starr, Kevin and Richard J. Orsi eds. Rooted in Barbarous Soil: People, Culture, and Community in Gold Rush California (2001), articles by scholars

- Strobridge, William F. (1994). Regulars in the Redwoods, The U.S. Army in Northern California, 1852-1861. Arthur Clark Company.

- Tutorow , Norman E. Leland Stanford Man of Many Careers(1971)

- Williams, R. Hal. The Democratic Party and California Politics, 1880-1896 (1973)

See also

- California

- Maritime history of California

- Politics of California to 1899

- Califas

- Califia

- Calafia

- Cali (disambiguation)

- origin of the name California

- History of the west coast of North America

External links

- Gold, Greed & Genocide

- "African Ancestry in California: More about Queen Califia" at the AfriGeneas: African Ancestored Genealogy official website.

- Museum of the Siskiyou Trail

- "Snakes in the Grass: Copperheads in Contra Costa?" article by William Mero at the Contra Costa County Historical Society official website.

- "Why it's called 'California' ", an excerpt from a doctoral dissertation by Craig Chalquist.

- Robert B. Honeyman Jr. Collection of Early Californian and Western American Pictorial Material in Trove.net

- The French in Early California

- The Bear Flag Museum

- Bancroft History of California Vol V. Bear Flag Revolt

Template:California Template:U.S. political divisions histories