Snakebite

| Snakebite | |

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | ICD10 F84.0-F84.1 |

| ICD-9 | 989.5 |

| MedlinePlus | 000031 |

A snakebite, or snake bite, is a bite inflicted by a snake. This article will discuss the etiology of a snakebite, along with prevention tips and, in the unfortunate event that the victim has been bitten by a venomous snake, recommended pre-hospital treatment.

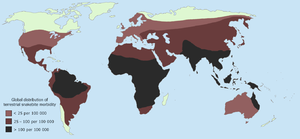

Frequency and statistics

Since reporting is not mandatory, many snakebites go unreported. Consequently, no accurate study has ever been conducted to determine the frequency of snakebites on the international level. However, some estimates put the number at 2.5 million bites, resulting in perhaps 125,000 deaths. [1] Worldwide, snakebites occur most frequently in the summer season, especially during the months of April and September, when snakes are active and humans are outdoors[1]. Agricultural and tropical regions report more snakebites than anywhere else. [2] Victims are typically male and between 17 and 27 years of age[1].

A late 1950s study estimated that 45,000 snakebites occur each year in the United States (Parrish 1966). Despite this large number, only 7,000-8,000 of those snakebites are actually caused by venomous snakes, resulting in an average of 10 deaths. [3] [4] This puts the chance of survival at roughly 499 out of 500. The majority of bites in the United States occur in the southwestern part of the country, in part because rattlesnake populations in the eastern states are much lower (Russell 1983).

Most snakebite related deaths in the United States are attributed to eastern and western diamondback rattlesnake bites. Children and the elderly are most likely to die (Gold & Wingert 1994). The state of North Carolina has the highest frequency of reported snakebites, averaging approximately 19 bites per 100,000 persons. The national average is roughly 4 bites per 100,000 persons (Russell 1980).

Most snakebites are caused by non-venomous snakes. Of the roughly 3,000 known species of snake found worldwide, only 15 percent are considered dangerous to humans (Russell 1990). Snakes are found on every continent except Antarctica. The most diverse and widely distributed snake family, the Colubrids, has only a few members which are harmful to humans. Of the 120 known indigenous snake species in North America, only 20 are venomous to human beings, all belonging to the families Viperidae and Elapidae. [5] However, every state except Maine, Alaska, and Hawaii is home to at least one of 20 venomous snake species. [6]

Since the act of delivering venom is completely voluntary, all venomous snakes are capable of biting without injecting venom into their victim. Such snakes will often deliver such a "dry bite" (about 50% of the time [7]) rather than waste their venom on a creature too large for them to eat. Some dry bites may also be the result of imprecise timing on the snake's part, as venom may be prematurely released before the fangs have penetrated the victim’s flesh.

| Landmasses | Population (x106) | Total number of bites | No. of envenomations | No. of fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 730 | 25,000 | 8,000 | 30 |

| Middle East | 160 | 20,000 | 15,000 | 100 |

| USA and Canada | 270 | 45,000 | 6,500 | 15 |

| Central and South America | 400 | 300,000 | 150,000 | 5,000 |

| Africa | 760 | 1,000,000 | 500,000 | 20,000 |

| Asia | 3,500 | 4,000,000 | 2,000,000 | 100,000 |

| Oceania | 20* | 10,000 | 3,000 | 200 |

| Total | 5,840 | 5,400,000 | 2,682,500 | 125,345 |

*Population at risk

Prevention

Snakes are most likely to bite when they feel threatened, are startled, provoked, and/or have no means of escape when cornered. If you or your party encounters a snake you should always assume it is dangerous and leave the vicinity. Unless you are an expert, there is no practical way to safely identify any snake species as appearances vary dramatically.

Snakes are likely to approach residential areas when attracted by prey, such as rodents. If it is a feasible option, practice pest control and snakes should not be an issue. If you live in an area with many snakes you may want to educate yourself on the species in your area. Likewise, if you plan to spend extended periods of time in areas of the world such as Africa, Australia, India, and southern Asia, it may be wise to research some of the more dangerous snakes inhabiting the region. If anything, you may at least be more wary of their presence and, as a result, less likely to be bitten.

Sturdy over-the-ankle boots, loose clothing and responsible behavior offer excellent protection from snakebites when in the wilderness. Give snakes plenty of warning that you are approaching by putting slight emphasis on your footsteps. The rationale behind this is that the snake will feel the vibrations and flee from the area. However, this generally only applies to North America as some larger and more aggressive snakes in other parts of the world, such as king cobras and black mambas, will actually protect their territory. In this case, if you run into a snake, stop moving and wait for several minutes. If the snake has not yet fled, slowly back away from the area.

If you are camping and decide to gather firewood at night, use a flashlight and, for your sake, do not go outside barefoot. Approximately 85% of the natural snakebites occur below the victims' knees. [9] Snakes may be unusually active during especially warm nights with ambient temperatures exceeding 70˚F., and a person not wearing footwear will have no protection from a potential bite.

It is advisable not to reach blindly into hollow logs, flip over large rocks, and enter old cabins or other potential snake hiding-places. If you are a rock climber, do not grab ledges or crevices without first looking (this does not mean poking your finger or a stick in the crevice) as snakes are coldblooded creatures and oftentimes sunbathe atop rock ledges.

If you own a pet snake that you know is capable of causing injury, or handle snakes as a hobby, always act with caution - approximately 65% of snakebites occur to the victims’ hands or fingers. Use your common sense and do not drink alcohol, or you may start acting foolishly once you are intoxicated. In fact, in the United States more than 40% of snakebite victims intentionally put themselves in harms way by attempting to capture wild snakes or by carelessly handling their dangerous pets. Further yet, 40% of that number had a blood alcohol level of 0.1 percent or more (Kurecki, et al 1987).

Avoid snakes that appear to be dead, as some species will actually rollover on their backs and stick out their tongue to fool potential threats. Even if a snake's head is detached from its body you should not attempt to pick it up as the reflex action of a snake's jaw muscles may cause it to "bite" you. This may be just as dangerous as a bite from a live snake (Gold & Barish 1992).

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of all snakebites are panic, fear and emotional instability, which may cause symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, vertigo, fainting, tachycardia, and cold, clammy skin (Kitchens & Mierop 1987). Television, literature and folklore are in part responsible for the hype surrounding snakebites, and a victim may have unwarranted thoughts of imminent death.

Dry snakebites, and those inflicted by a non-venomous species, are still able to cause severe injury to the victim. There are several reasons for this; a snakebite which is not treated properly may become infected (as is often reported by the victims of cobra bites whose fangs are capable of inflicting deep puncture wounds), the bite may cause anaphylaxis in certain people, and the saliva and fangs of the snake may harbor many dangerous microbial contaminants, including Clostridium tetani. An infection which is neglected may spread, and, in the worst cases, even kill the victim.

Most snakebites, whether by a venomous snake or not, will have some type of local effect. Usually there is minor pain and redness, but this varies depending on the site. Bites by vipers and some cobras may be extremely painful, with the local tissue sometimes becoming tender and severely swollen within 5 minutes. This area may also bleed and blister.

Interestingly, bites caused by the Mojave rattlesnake and the speckled rattlesnake reportedly cause little or no pain despite being serious injuries. Victims may also describe a “rubbery,” “minty,” or “metallic” taste if bitten by certain species of rattlesnake. Spitting cobras and Rinkhals can spit venom in their victims’ eyes. This results in immediate pain, vision problems, and sometimes blindness.

Some Australian elapids and most viper envenomations will cause coagulopathy, sometimes so severe that a person may bleed spontaneously from the mouth, nose, and even old, seemingly-healed wounds. Internal organs may bleed, including the brain and intestines and will cause ecchymosis (bruising) of the victim's skin. If the bleeding is left unchecked the victim may die of blood loss.

Venom emitted from cobras, most sea snakes, mambas, and other elapids contain toxins which attack the nervous system. The victim may present with strange disturbances to their vision, including blurriness. This is commonly due to the venom paralyzing the ciliary muscle, which is responsible for focusing the lens of the eye, but can be the result of eyelid paralysis as well. Victims will also report paresthesia throughout their body, as well as difficulty speaking and breathing. Nervous system problems will cause a huge array of symptoms, and those provided here are not exhaustive. In any case, if the victim is not treated immediately they may die from respiratory failure.

Venom emitted from some Australian elapids, the Russell’s viper, almost all vipers, and all sea snakes causes necrosis of muscle tissue. Muscle tissue may begin to die throughout the body, a condition known as rhabdomyolysis. Dead muscle cells may even clog the kidney which filters out proteins. This, coupled with hypotension, can lead to kidney failure, and, if left untreated, eventually death.

Treatment

It is not an easy task determining whether or not a bite by any species of snake is life-threatening. A bite by a copperhead on the ankle is usually a moderate injury to a healthy adult, but a bite to a child’s abdomen or face by the same snake may well be fatal. The outcome of all snakebites depends on a multitude of factors; the size, physical condition, and temperature of the snake, the age and physical condition of the victim, the area and tissue bitten (e.g., foot, torso, vein or muscle, etc.), the amount of venom injected, and finally the time it takes for the patient to be treated and the quality of treatment.

Snake identification

Identification of the snake is important in planning treatment, but not always possible. Ideally the dead snake would be brought in with the patient, but in areas where snake bite is more common, local knowledge may be sufficient to recognise the snake.In countries where polyvalent anti-snake venoms onll are available identification of snake is not of much significance.

The three types of poisonous snake that cause the majority of major clinical problems are the viper, krait and cobra. Knowledge of what species are present locally can be crucially important, as is knowledge of typical signs and symptoms of envenoming by each species of snake.

A scoring systems can be used to try and determine biting snake based on clinical features,[2] but these scoring systems are extremely specific to a particular geographical area.

First Aid

Snakebite first aid recommendations vary, in part because different snakes have different types of venom. Some have little local effect, but life-threatening systemic effects, in which case containing the venom in the region of the bite (e.g., by pressure immobilization) is highly desirable. Other venoms instigate localized tissue damage around the bitten area, and immobilization may increase the severity of the damage in this area, but also reduce the total area affected; whether this trade-off is desirable remains a point of controversy.

Because snakes vary from one country to another, first aid methods also vary; treatment methods suited for rattlesnake bite in the United States might well be fatal if applied to a tiger snake bite in Australia. As always, this article is not a legitimate substitute for professional medical advice. Readers are strongly advised to obtain guidelines from a reputable first aid organization in their own region, and to beware of homegrown or anecdotal remedies.

However, most first aid guidelines agree on the following:

- Protect the patient (and others, including yourself) from further bites. While identifying the species is desirable, do not risk further bites or delay proper medical treatment by attempting to capture or kill the snake. If the snake has not already fled, carefully remove the patient from the immediate area.

- Keep the patient calm and call for help to arrange for transport to the nearest hospital emergency room, where antivenom for snakes common to the area will often be available.

- Make sure to keep the bitten limb in a functional position and below the victim's heart level so as to minimize blood returning to the heart and other organs of the body.

- Do not give the patient anything to eat or drink. This is especially important with consumable alcohol, a known vasodilator which will speedup the absorption of venom. Do not administer stimulants or pain medications to the victim, unless specifically directed to do so by a physician.

- Remove any items or clothing which may constrict the bitten limb if it swells (rings, bracelets, watches, footwear, etc.)

- Keep the patient as still as possible.

- Do not incise the bitten site.

Many organizations, including the American Medical Association and American Red Cross, recommend washing the bite with soap and water. However, do not attempt to clean the area with any type of chemical.

Pressure immobilization

Pressure immobilization may not be appropriate for cytotoxic bites such as those of most vipers[3][4] [5], but is highly effective against neurotoxic venoms such as those of most elapids[6][7][8]. Developed by Struan Sutherland in 1978[9], the object of pressure immobilization is to contain venom within a bitten limb and prevent it from moving through the lymphatic system to the vital organs in the body core. This therapy has two components: pressure to prevent lymphatic drainage, and immobilization of the bitten limb to prevent the pumping action of the skeletal muscles. Pressure is preferably applied with an elastic bandage, but any cloth will do in an emergency. Bandaging begins two to four inches above the bite (i.e. between the bite and the heart), winding around in overlapping turns and moving up towards the heart, then back down over the bite and past it towards the hand or foot. Then the limb must be held immobile: not used, and if possible held with a splint or sling. The bandage should be about as tight as when strapping a sprained ankle. It must not cut off blood flow, or even be uncomfortable; if it is uncomfortable, the patient will unconsciously flex the limb, defeating the immobilization portion of the therapy. The location of the bite should be clearly marked on the outside of the bandages. Some peripheral edema is an expected consequence of this process.

Apply pressure immobilization as quickly as possible; if you wait until symptoms become noticeable you will have missed the best time for treatment. Once a pressure bandage has been applied, it should not be removed until the patient has reached a medical professional. The combination of pressure and immobilization can contain venom so effectively that no symptoms are visible for more than twenty-four hours, giving the illusion of a dry bite. But this is only a delay; removing the bandage releases that venom into the patient's system with rapid and possibly fatal consequences.

For more information on this technique visit http://www.snakebite-firstaid.com/. Besides an easy-to-use First Aid description, much info on snakes and their venom.

Outmoded treatments

The following treatments have all been recommended at one time or another, but are now considered to be ineffective or outright dangerous, and should not be used under any circumstances. Many cases in which such treatments appear to work are in fact the result of dry bites.

- Application of a tourniquet to the bitten limb.

- Cutting open the bitten area.

- Application of potassium permanganate.

- Use of electroshock therapy. Although still advocated by some, animal testing has shown this treatment to be useless and potentially dangerous (cf Postgrad Med, 1987a, Postgrad Med, 1987b, Ann Emerg Med, 1988, Toxicon, 1987, Ann Emerg Med, 1991).

- Suctioning out venom, either by mouth or with a pump. Suctioning by pump removes a clinically insignificant quantity of venom (Annals of Emergency Medicine, February 2004), and the resultant bruising speeds the venom's absorption. Suctioning by mouth presents a risk of further poisoning through the mouth's mucous tissues (Riggs, et al 1987). The well-meaning family member or friend may also release bacteria into the victim’s wound, leading to infection.

- Application of ice. The process of chilling the wound area or the affected limb should certainly be avoided. This procedure would have the effect of slowing the blood flow to the area, thus preventing the natural dissipation of the venom and likely increasing its damaging effects.

In extreme cases, where the victims were in remote areas, all of these misguided attempts at treatment have resulted in injuries far worse than an otherwise mild to moderate snakebite. In worst case scenarios, thoroughly constricting tourniquets have been applied to bitten limbs, thus completely shutting off blood flow to the area. By the time the victims finally reached appropriate medical facilities their limbs had to be amputated.

See also

- Snake

- Harmful snakes

- Snake venom

- Antivenom

- Medical emergency

- Outdoor emergency care

- Wilderness first aid

- Wilderness emergency medical technician

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wingert, Willis A.; Chan L. (1988). "Rattlesnake bites in southern California and rationale for recommended treatment.". Western Journal of Medicine 148 (1): 37–44. Retrieved on 2006-05-26.

- ↑ Pathmeswaran A, Kasturiratne A, Fonseka M, et al. (2006). "Identifying the biting species in snakebote by clinical features: an epidemiological tool for community surveys". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 100: 874–8 issue=9.

- ↑ Tony Celenza, MBBS, FACEM, FFAEM. "Simulated Field Experience in the Use of the Sam Splint for Pressure Immobilization of Snakebite". Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 13 (2): 184–185.

- ↑ Bush SP; Green SM; Laack TA; Hayes WK; Cardwell MD; Tanen DA (December 2004). "Pressure-Immobilization Delays Mortality and Increases Intra-compartmental Pressure after Artificial Intramuscular Rattlesnake Envenomation in a Porcine Model". Annals of Emergency Medicine 44 (6): 599–604. Retrieved on 2006-06-25.

- ↑ Sutherland SK; Coulter AR (March 1981). "Early management of bites by the eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus): studies in monkeys (Macaca fascicularis)". The American Journal of Triopical Medicine and Hygiene 30 (2): 497–500. Retrieved on 2005-06-25.

- ↑ Ken D. Winkel, PhD (Australian Venom Research Unit, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia). "Struan Sutherland's “Rationalisation Of First-Aid Measures For Elapid Snakebite”—A Commentary". Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 16 (3): 160–163. Retrieved on 2006-06-25.

- ↑ Sutherland SK (December 1992). "Deaths from snake bite in Australia 1981-1991". The Medical journal of Australia 157 (11–12): 740–746. Retrieved on 2006-06-25.

- ↑ Sutherland SK; Leonard RL (December 1995). "Snakebite deaths in Australia 1992-1994 and a management update.". The Medical journal of Australia 163 (11–12): 616–618. Retrieved on 2006-06-25.

- ↑ S.K. Sutherland; A.R. Coulter; R.D. Harris (1979). "Rationalisation of first-aid measures for elapid snakebite". Lancet 313 (8109): 183–186.

- Gold, Barry S., Willis A. Wingert, et al. "Snake venom poisoning in the United States: A review of therapeutic practice", Southern Medical Journal, June 1994, 87(6):579-89.

- Gold, Barry S., Barish RA. “Venomous snakebites: current concepts in diagnosis, treatment, treatment, and management.” Emerg Med, Clin North Am 1992;10:249-67.

- Kitchens CS, Van Mierop LHS. “Envenomation by the eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius): a study of 39 victims.” JAMA 1987;258:1615-8.

- Kurecki, Brownlee, et al. The Journal of Family Practice, 1987, 25(4):386-392

- Palm Beach Herpetological Society. Venomous Snake Bite". Retrieved on 2006-06-26.

- Parrish HM. “Incidence of treated snakebites in the United States.” Public Health Rep 1966;81:269-76.

- cf Postgrad Med, 1987, Oct;82(5):32; Postgrad Med, 1987, Aug;82(2):42; Ann Emerg Med, 1988, Mar;17(3):254-256; Toxicon, 1987;25(12):1347-1349; Ann Emerg Med, 1991, Jun;20(6):659-661.

- Riggs et al. Rattlesnake evenomation with massive oropharyngeal edema following incision and suction (Abstract) AACT/AAPCC/ABMT/CAPCC Annual Scientific Meeting, 1987.

- Russell, Findlay E. Ann Rev Med, 1980, 31:247-59.

- Russell, Findlay E. “Snake venom poisoning.” Great Neck, N.Y.: Scholium, 1983:163.

- Russell, Findlay E. “When a snake strikes.” Emerg Med, 1990;22(12):20-5, 33-4, 37-40, 43.

- "Suction for Venomous Snakebite: A Study of 'Mock Venom' Extraction in a Human Model", February 2004, Annals of Emergency Medicine, p. 181.

- Sullivan JB, Wingert WA, Norris Jr RL. North American Venomous Reptile Bites. Wilderness Medicine: Management of Wilderness and Environmental Emergencies, 1995; 3: 680-709.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (November 2002) "For Goodness Snakes! Treating and Preventing Venomous Bites". Retrieved December 30, 2005.

- World Health Organization. "Animal sera". Retrieved December 30, 2005.

Further reading

- J. Jones, MD; Dispelling The Snakebite Myth

- First Aid for Snake Bites

- Snake envonomation treatment

- Poisonous snakes and lizards

- Firsthand account of a snakebite (with graphic photos of victim's hand through multiple stages of surgery)