Tet Offensive

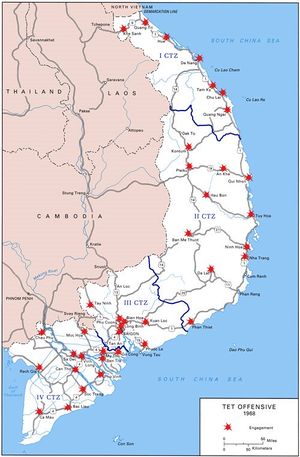

On January 31, 1968, during the traditional cease-fire of the Tet holiday, Commuist forces attacked 36 of 44 provincial capitals and 5 of 6 major cities. The North Vietnamese called it Tet Mau Than or Tong Kong Kich/Tong Kong Ngia (TCK/TCN, General Offensive/Uprising) [1] It is unclear to which the Battle of Khe Sanh was part of an overall strategy to draw American forces away from the cities. Some agencies did not expect it, while others had suspected an oncoming offensive.

North Vietnamese planners expected popular uprising (khnoi nghai), but this almost completely failed to occur. many South Vietnamese demonstrated stronger support for the ARVN. [2] However, the Tet Offensive had a devastating impact on Johnson's political position in the U.S., and in that sense was a strategic victory for the Communists. [3]

Warning

In U.S. intelligence, three components appeared to have predicted the Tet action:[4]

- the Army communications intelligence group supporting MG Frederick C. Weyand's 3rd Corps[5]

- National Security Agency, although it did not recognize the scope of the offensive[6]

- CIA's Saigon Station

These failed, however, to make much impression outside the areas tactically concerned. Indeed, they were being delivered in a context where senior officials did not want to hear contradictory information; In September 1967, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Walt Rostow said that told the Agency that because President Lyndon Baines Johnson wanted some "useful intelligence on Vietnam for a change," the CIA should prepare a list of positive (only) developments in the war effort, which Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms sent to Rostow with a dissenting cover note that Rostow removed. but Rostow pulled off that cover note and so was finally able to give the President a "good news" study from the CIA.[7]

CIA

Reports from the Saigon station may have been strong warnings, but two assessments, from Bob Layton, on 21 November and 8 December 1967) based on human-source intelligence from prisoner interrogations and documents. They suggested that the PAVN was planning some type of decisive defeat for Allied forces in 1968. In conflict with the attention being given to Battle of Khe Sanh, these indicators pointed to urban terrorism coupled by military attacks on cities. There was a strong Communist belief that the GVN was so unpopular that an urban attack could irreparably damage confidence in the ARVN. These assessments also pointed to increasing international pressure on the Johnson administration to end the war.

A more detailed analysis, on December 8, described a distinct change in Communist thinking, away from the protracted war attritional model to something more decisive. It cited documentation of "an all-out military and political offensive during the 1967-68 winter-spring campaign [the period beginning around Tet] designed to gain decisive victory...large-scale continuous coordinated attacks by main force units, primarily in mountainous areas close to border sanctuaries"--a strategy subsequently reflected in the enemy's major attacks on Khe Sanh--and "widespread guerrilla attacks on large US/GVN units in rural and heavily populated areas." The PAVN saw the urban population as the center of gravity, not attrition to U.S. troops or the defeat of ARVN forces.

The plan was seen (emphasis added) "a serious effort to inflict unacceptable military and political losses on the Allies regardless of VC casualties during a US election year, in the hope that the US will be forced to yield to resulting domestic and international pressure and withdraw from South Vietnam." Even if the results did not force a settlement, the Communists would be in a "better position to continue a long-range struggle with a reduced force." He continued: "If the VC/NVN view the situation in this light, it is probably to their advantage to use their current apparatus to the fullest extent in hopes of fundamentally reversing current trends before attrition renders such an attempt impossible."

"In sum," the study's final sentence read, "the one conclusion that can be drawn from all of this is that the war is probably nearing a turning point and that the outcome of the 1967-68 winter-spring campaign will in all likelihood determine the future direction of the war."[8]

A 19 December report added more indicators that the NVA was preparing an all-out effort, although the Saigon analysts recognized the CIA Headquarters position that all of this exhortation might be an effort to bolster PAVN/VC morale.

At the Central Intelligence Agency, Undersecretary of State Nicholas deB. Katzenbach and Assistant Secretary of State Philip Habib were being briefed about a suspected offensive, probably at the end of Tet, when the word of the first attacks came. [9]

Attacks

A number of sources believed the urban attacks started prematurely on January 29, although there was an earlier planned intensification around Khe Sanh. Most of the urban attacks were on the night of Januare 30-31.

There had been an intThe fighting was most intense around Khe Sanh. There were three divisions of NVA regulars around Khe Sanh, possibly 25,000 men. Action began there around ten days before Tet, with probing attacks and exchanges of artillery fire. Two hill positions were captured on January 20, cutting the base from land routes. Attention in MACV and Washington was obsessed with Khe Sanh and other indicators of trouble were overlooked or down-graded. The main assaults did not begin until February 5. Lang Vei was over-run on February 7 and the lines at Khe Sanh were very heavily attacked, the camp only being preserved by massive airstrikes and artillery barrages (over 30,000 sorties were flown in defence of the base). After this the tempo slowed, the battle became more of a siege, although there were further NVA assaults on the 17-18th and the 29th. Khe Sanh was officially relieved on April 6 and fighting ended around April 14. Possibly 8,000 NVA soldiers died around Khe Sanh.

Urban areas outside Hue

Besides the symbolic targets in Saigon (III CTZ), and the very serious fighting in Hue (I CTZ, eight cities had substantial attacks.

Urban targets| City | ARVN CTZ | |

|---|---|---|

| Quang Nam | I CTZ | |

| Kontum | II CTZ | |

| My Tho | II CTZ | |

| Ban Met Thuot | II CTZ | |

| Nha Trang | II CTZ | |

| Ben Tre | ||

| Can Tho | ||

| Da Lat | II CTZ |

Hue

The harshest fighting came in the old imperial capital of Hue. The city fell to the PAVN, which immediately set out to identify and execute thousands of government supporters among the civilian population. The allies fought back with all the firepower at their command. House to house fighting recaptured Hue on February 24. In Hue, five thousand enemy bodies were recovered, with 216 U.S. dead, and 384 ARVN fatalities. A number of civilians had been executed while the PAVN held the city.

Nationwide, the enemy lost tens of thousands killed, US lost 1,100 dead, ARVN 2,300. The people of South Vietnam did not rise up. Pacification, however, suspended in half the country, and a half million more people became refugees.

Media events

They avoided American strongholds and targeted GVN government offices and ARVN installations, other than "media opportunities" such as attempting to a fight, by a small but determined squad, of the U.S. Embassy. [10]

References

- ↑ Hanyok, Robert J. (2002), Chapter 7 - A Springtime of Trumpets: SIGINT and the Tet Offensive, Spartans in Darkness: American SIGINT and the Indochina War, 1945-1975, Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency, p. 310

- ↑ Adams, Sam (1994), War of Numbers: An Intelligence Memoir, Steerforth Press

- ↑ Willbanks, James H. (2006), The Tet Offensive: A Concise History

- ↑ Ford, Harold R. (1997), Episode 3 1967-1968: CIA, the Order-of-Battle Controversy, and the Tet Offensive, CIA and the Vietnam Policymakers: Three Episodes 1962 - 1968, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, Ford Episode 3

- ↑ Ford Episode 3, General Weyand, to author, 17 April 1991. Weyand's communications intelligence battalion comander, LTC Norman Campbell, supports Weyand's accounts.

- ↑ Hanyok, pp. 326-333

- ↑ George Allen, The Indochina Wars, cited in Ford Episode 3

- ↑ Saigon telepouch FVSA 24242, 8 December 1967. CIA files, Job No. 80R01580R, DCI/ER Subject Files, Box 15, Folder 3, cited in Ford Episode 3

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don (2001), Tet! The Turning Point in the Vietnam War, JHU Press,pp. 18-20

- ↑ Oberdorfer, pp. 2-14