U.S. Electoral College

The Electoral College is the mechanism that selects the president and vice president of the United States.[1] It consists of 538 electors whose votes are allocated according to the results of popular elections held in each state and Washington, D.C.. The electors meet in December in their respective states and cast their votes, one for president and one for vice president. Congress counts the votes as certified by the appropriate authorities in each state and announces the President and Vice President. The electoral procedure was established in Article II of the Constitution and has operated since 1789, with one major change in 1804 to accommodate the newly emergent political party system. Only states have electoral votes (not territories), but the 23rd Amendment to the Constitution (1961) gave three electoral votes to the District of Columbia.

Each state is granted a number of electors equal to the total of its representatives and senators in the U.S. Congress. More populous states have more representatives and hence have more electoral votes; however, the addition of two votes per state for senators means that states are represented beyond just their population, which has an important effect for smaller states.

Since the early 19th century, each state chooses its electors based on a statewide popular vote for president. In 48 states, the entire slate of electors pledged to the candidate who receives the most votes statewide is elected. In Maine and Nebraska, two of each state's electors are chosen by the statewide vote (one for each senator), and each remaining elector is chosen by the vote in each congressional district.

The Electoral College system is highly controversial, especially since the 2000 presidential election. Various reforms have been proposed but none has been approved by Congress.

Institutional design

The Electoral College was devised by Constitutional Convention of 1787 as a solution to the problem of selecting a President. Early proposals were to have Congress elect the president, to have the state legislatures elect the President, or to elect the President by nationwide popular vote. Congressional election was rejected as being possibly too divisive, too easy to corrupt, and as eroding the separation of powers. State legislative election was rejected as leaving a president beholden to states who might wish to erode national authority. Popular voting was rejected because, at the time, communication between states was not very good, and there would be very few nationally known persons, and thus people would tend to vote for their state's "favorite son", making it difficult to obtain a majority. Further, small states feared that popular vote would allow a combination of large states to dominate the presidency. Eventually, a "Committee of Eleven" proposed that the President should be elected by electors from each state, similar to the way that the Pope is elected by the College of Cardinals, or the Holy Roman Emperor was elected. The structure of the Electoral College can be traced to the Centurial Assembly system of the Roman Republic.[2]

While the Electoral College has been a frequent source of controversy ever since it was put into practice, it was not subject to much criticism by antifederalist opponents to the Constitution. In fact, in Federalist Paper #68, Alexander Hamilton described the institution as "if not perfect, at least excellent." His justification, which explains how the Electoral College system satisfies five desiderata, sheds light onto the Constitution's framers' political theory and priorities.

Original Electoral College

Originally the person with the highest number of votes, if the number be a majority of the electors, would be elected President. The person with the second-highest number of votes would be elected Vice President.

If two persons exceeded the half-way mark and tied, the House of Representatives, voting as states and not individuals, would choose between the two names. If no single name exceeded the half-way mark, the top five names would be placed before the House and the House would decide from those five; voting, again, as whole states. The person with the most votes would become President, and the person with the second-most votes would become Vice-President. If there was a tie for second place after the selection of the President, the Senate would choose the Vice President between these names. Voting in the Senate would be as individuals, not as states.

Constitutional amendments

Since the Constitution's ratification, two amendments have altered the Electoral College's operations. The first was the 12th Amendment, which was proposed in 1803 and ratified in 1804. It made a small but critical change that took parties into account. The 12th Amendment begins

| “ | The electors shall meet in their respective states and vote by ballot for President and Vice-President, one of whom, at least, shall not be an inhabitant of the same state with themselves; they shall name in their ballots the person voted for as President, and in distinct ballots the person voted for as Vice-President | ” |

The name with the majority of the votes for President is named President. If there is no majority in the ballots for President, the three highest vote-getters are voted on by the House, voting as states. The winner of that vote is President.

The name with the majority of the votes for Vice President is named Vice President. If there is no majority in the ballots for Vice President, the two highest vote-getters are voted on by the Senate, Senators voting as individuals. The winner of that vote is Vice President.

The 12th Amendment also closed one loophole in the process: the qualifications for Vice President were explicitly made the same as those for President.

In the first election following the ratification of the 12th Amendment, in 1804, Jefferson received 162 votes to 14 for Charles Pinckney for President; George Clinton received 162 votes to 14 for Rufus King for the office of Vice President.

23rd Amendment

In 1961, the 23rd Amendment was ratified. The 23rd grants the national capital electoral votes as if it were a state, though it may not have more votes than the state with the least number of electors. Since ratification of the 23rd Amendment, Washington D.C. has had three electoral votes.

The Electoral College in practice

In the first two Presidential elections, in 1788 and 1792, George Washington was elected President, receiving a vote from every elector, 69 in 1788 and 132 in 1792. John Adams received 34 electoral votes in 1788 and 77 in 1792, and was elected Vice-President. George Clinton of New York received 50 votes in 1792.[3]

Elections of 1796 and 1800

As political parties suddenly emerged on a national basis, the problems with the original scheme became apparent. In the election of 1796, political rivals Federalist John Adams and Republican Thomas Jefferson obtained 71 and 68 electoral votes respectively. Adams's running mate was Thomas Pinckney, who came in third with 59 votes; Jefferson's running mate was Aaron Burr, who came in fourth with 30 votes. Adams and Jefferson were therefore elected, even though they came from opposing parties. The emergence of the First Party System was an unexpected development, for the nation now had two equally matched parties that operated in each state and presented national tickets.

The crisis came in 1800: Adams and Pinckney were again on the Federalist Party ticket, and Jefferson and Burr on the Republican ticket. This time, however, Jefferson and Burr both got 73 electoral votes, Adams received 64, and Pinckney 63. The tie threw the election to the House.[3] Though Jefferson was the intended Presidential candidate, Burr supporters and Adams supporters repeatedly voted to elect Burr as President, resulting in repeated votes that resulted in ties. Finally Federalist Party leader Alexander Hamilton, alarmed at the prospect of President Burr led Federalists to cast blank votes which allowed for Jefferson's election. With rumors abounding of Virginia militia marching on Washington, Federalist James Bayard, the sole Congressman from Delaware, played the critical role in securing the choice of Jefferson.[4]

Selection of electors

The Constitution specifies that the manner of choosing electors is up to each state legislature. Initially different states adopted different methods. Some state legislatures decided to choose the Electors themselves. Others decided on a direct popular vote for Electors either by congressional district or at large throughout the whole state. Still others devised some combination of these methods. But in all cases, Electors were chosen individually from a single list of all candidates for the position.

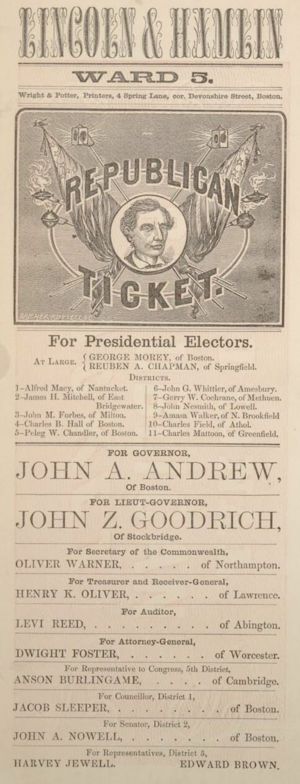

As late as the 1920 election, for example, it was possible for voters in 39 states to vote for electors pledged to different presidential candidates, because the ballots listed the names of individual candidates for elector and the voter could vote for any assortment of electors. (This arrangement lasted until 1980 in at least one state, South Carolina.) In fact, in some states, the names of the actual presidential candidates did not even appear on the ballot, although the candidates for elector were usually identified at least by political party. [5]

During the 1800's, two trends in the states altered and more or less standardized the manner of choosing Electors. The first trend was toward choosing Electors by the direct popular vote of the whole state (rather than by the state legislature or by the popular vote of each Congressional district). By 1836, all states except South Carolina had moved to choosing their Electors by a direct statewide popular vote. South Carolina persisted in choosing them by the state legislature through 1860. Today, all states choose their electors by direct statewide election except Maine and Nebraska.[2] Maine adopted a system in 1969, in place for the 1972 election, in which two of the electors are chosen by the state-wide vote (one for each Senator), and the remaining electors are chosen by the Congressional district vote. Nebraska adopted the same system in 1992, in time for that year's election.[6] However, since the system has been in place in both states, the result has been the same as "winner-takes-all" because the district-wide voting mirrored the state-wide voting.

Nomination of electors

Prior to a presidential election, each political party names a list of persons to serve as electors should that party win the state-wide vote. For example, in Vermont, state law mandates that major parties nominate electors at the party platform convention. Minor party candidates may select electors by petition. The party elector lists are sent to the Vermont Secretary of state. After the votes in the presidential election are counted, the electors nominated by the winning party are declared the Vermont electors. In California, however, the electors for each party's presidential candidate are nominated by the congressional and senatorial candidates from that party running in the same election; in the absence of a candidate, the state party chairman selects the nominee elector.

The major parties typically choose party loyalists to appear on their list of elector nominees, to avoid problems with faithless electors.

Election of 1960

In the election of 1960, in Alabama held a Democratic party primary to select electors to appear on the ballot in the general election. The Democratic Party's primary resulted in a slate of 5 electors pledged to the party nominee (Kennedy) and 6 unpledged electors. In the general election, voters could vote for each of 11 electors individually; all 11 Democrat electors came ahead of all of Nixon's electors. The 6 unpledged electors voted for Senator Harry Byrd of Virginia for President, as did 5 unpledged electors elected in Mississippi.[7]

December meeting of the College

Following the presidential election, the electors from each state meet in a place specified by state law. The date the electors meet is set in federal law, specifically to be held on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December. [8]

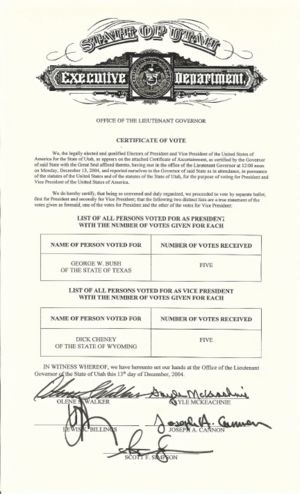

The assembled electors make and sign six certificates noting the votes for president and for vice president.[9] After the certificates are sealed, one is mailed to the president of the Senate (the Vice President); two are delivered to the state secretary of state - one is held in case it is called for by the President of the Senate and the other is held for public inspection; two are mailed to the Archivist of the United States - one is held in case it is called for by the President of the Senate and the other is held for public inspection; the last is delivered to a judge in the district where the meeting took place. [10] Each copy is accompanied by the Certificate of Ascertainment, which is prepared by the state's governor, listing the electors chosen and the number of votes received. [11]

In 2000, Election Day was 7 November and Electoral College Day was 18 December; in 2004, the dates were 2 November and 13 December; in 2008, they will be 4 November and 15 December.

Faithless Electors

The term faithless elector is used to denote an elector who does not vote as expected. For example, if candidate A wins the popular vote in a state, that state's electors are expected to place candidate A's name on their presidential ballots.

The Constitution, however, does not dictate any such requirement for electors - it simply notes that states select electors any way they wish, and that electors then vote. Some states have civil penalties for faithless electors, but there is argument about the constitutionality of such laws.

Faithless electors are rare and thus far have not made a difference in the outcome.[12]

Mistakes in voting have been rare. [13]

Impact of the Electoral College

The Electoral College system usually magnifies the margin of victory in presidential elections--a small win in terms of popular votes becomes a large win in electoral votes. The focus on winning states, rather than overall popular vote, affects the political strategies of presidential candidates. Political campaigns concentrate their efforts on those states where the outcome is least certain, and the distribution of electoral votes requires presidential candidates to have broad geographic appeal to be competitive. A study of the impact of electoral college on turnout in the 2000 election shows that state battleground status impacted state-level turnout through its effect on media spending and candidate visits.[14]

Voters have an unequal representation in the Electoral College. Wyoming is the smallest state in terms of population, with 493,782 persons as of the 2000 census, and three electoral votes. This gives each person in Wyoming 6.075 millionths of an electoral vote (or 164,594 persons per electoral vote). California, by contrast, had 33,871,648 persons as of the 2000 census, and 55 electoral votes. This gives each person in California 1.623 millionths of an electoral vote (or 615,848.15 persons per electoral vote), about 26% of the "vote power" than each person in Wyoming. From this perspective, Wyoming (and small states generally) appear more powerful.

However, from the perspective of the candidates, large states are disproportionately important because of the size of the jackpot. Therefore candidates spend far more time and money in one large state than in several smaller states combined. From this perspective voters in large states are more important than those in small states. The curious result is that voters in small states, and voters in large states both think the system gives them an advantage, so they are both reluctant to change.

Primarily because most states allocate electors on a winner-take-all basis, it is possible for the electoral college winner to not have a majority of the popular vote. In 1824, 1876, 1888, 1960 and 2000, presidential candidates with fewer popular votes than their opponent won the electoral vote. In several election years, including 1912, 1916, 1948, 1960, 1968, 1992, 1996, and 2000, the winner of the electoral vote won less than 50% of the popular vote, although except in 1960 and 2000, the electoral college winner had more popular votes than other candidate.

Electoral College controversies

The Electoral College is controversial and has become more so since the election in 2000. Its critics offer two major criticisms against it today: the College's disproportionate rates of representation, and the occasional election of a president who is not the winner of the national popular vote. Additionally, critics believe that the electoral college may depress voter turnout, and worry that faithless electors could swing the results of an election.

Critics argue that electing a minority president is a flaw of the Electoral College system, as is the disproportionate vote power of people in smaller states. In a democracy, critics argue, every person's vote ought to have the same weight, and the Electoral College violates that principle.[15] Critics of the electoral college argue that since each state is entitled to the same number of electoral votes regardless of its voter turnout, there is no incentive in the states to encourage voter participation.

Supporters of the electoral college contend that a republican system is mandated by the Constitution, not a democracy, and that the disproportionate number of votes for small state was a compromise agreed to by every state in 1787-88 and one essential to having a Constitution in the first place.

Judith Best, a researcher of the electoral college and professor at SUNY Cortland, argues that the presidential election process should satisfy six goals: selection of a president with broadly distributed popular support, a swift and decisive selection of the winner, preservation of the moderate two-party system, politically effective representation that include minority views, preservation of the separation of powers, and preservation of the federal principle. Best argues that only the existing system satisfies all of these requirements.[16]

Supporters of the Electoral College argue that the system contributes to the cohesiveness of the country by requiring a distribution of popular support to be elected president. Without such a mechanism, they point out, presidents would be selected either through the domination of one populous region over the others or through the domination of large metropolitan areas over the rural ones.[2] In the absence of the Electoral College, presidential candidates would focus almost entirely on large states to the exclusion of smaller states, while at present, they focus more on states where the result is less certain, and the disproportionate voting power of the small states ensures that candidates take into account the political values and concerns of small states as well as large.[17]

Supporters of the electoral college also argue that by partitioning votes by state, the uncertainty and instability caused by recounts in extremely close races (such as in 2000) are limited in scope to one or two states, rather than causing national recounts.[18] Another argument raised in favor of the electoral college is that the effects of any fraud in the election process, such as the casting of fraudulent ballots, are limited to one state, and so only in unusual circumstances (such as the 1960 presidential election) can fraud potentially effect the outcome.[19]

Turner (2007) argues in favor of continuing the electoral college system and discusses the history of reform proposals. Despite periodic complaints from critics, especially in the wake of the election of George W. Bush in 2000, the electoral college still offers more advantages than a direct or popular vote for president. These advantages include a two-party system based on coalition and compromise rather than division, the complexities and expenses of a runoff in a populist national election if no candidate achieves a popular plurality, a fragmented electorate, and the difficulties of a national recount in a disputed election. Advocates of abolishing the electoral college should be wary of the unintended consequences in other proposals, warns Turner.[20]

Reform proposals

Many proposals for Electoral College reform have been proposed. Between 1889 and 1946, 109 constitutional amendments to reform it were introduced in Congress, with another 265 between 1947 and 1968. In 1967, an American Bar Association commission recommended that the Electoral College be scrapped and replaced by direct popular vote for the president, with a provision for a runoff if no candidate achieved the threshold of 40 percent of the votes. The ABA plan, introduced by Indiana Senator Birch Bayh and endorsed by the Nixon White House, passed the House 338-70, but died on a filibuster in the Senate led by North Carolina Senator Sam Ervin.[21]

Some proposals would require constitutional amendments, while others could be adopted on a state-by-state basis. Most face significant political challenges to adoption. Panagopoulos (2004) reports that public opinion polls conducted between 1948 and 2002 show considerable support for electoral reform. Support was found for the abolition of the Electoral College, for changes to the way presidential candidates are nominated, and for alterations to campaign funding and procedures. There was also support for alterations in voting procedures.

Bugh (2004) seeks to understand why attempts to reform the unpopular and heavily criticized Electoral College repeatedly fail. He argues that national electoral structures contribute to such amendment efforts by establishing incentives for pursing and deterrents for stopping reform. Bugh posits that the state of the electoral landscape constrains participants' arguments over amending the national electoral system. These structures include the distribution of electoral votes among states, the intensity of two-party competition, and pattern of pivotal politics. These arrangements change over time in response to various factors from population shifts to civil rights laws, presenting new reasons for and against altering the electoral process. Bugh looked at proposals debated in Congress from 1948 to 1979, focusing on appeals to these features of the electoral landscape. Only twice during the twentieth century did the House or Senate approve an amendment to the system; once in 1950 for proportional distribution of electoral votes and in once in 1969 for direct election.

Proposals regarding allocation of electoral votes

These proposals affect how the states allocate electoral votes, and would not change the constitutional nature of the Electoral College. Some proponents may advocate constitutional change or federal legislation to implement these ideas, but all that is necessary is state action.

Maine Plan

The Maine Plan is the arrangement for distribution of electoral votes used by Maine and Nebraska, where the plurality vote winner in each congressional district is allocated one elector, and the overall statewide plurality winner is allocated the two remaining votes. This proposal dilutes the influence of most states, as the number of Electoral College votes in contention is less the number in contention under a winner-take-all system. In states with strong majorities for one party, this proposal guarantees the other party a significant number of electoral votes. The organization Fairvote contends that this plan would have resulted in a Bush victory by 44 electoral votes in the 2000 election.[22]

After the 2000 presidential election, 21 states considered legislation to award their presidential electors using the district system, wherein one elector is awarded to the popular vote winner of each congressional district and the two state electors are awarded to the popular vote winner statewide. An initiative has been introduced in California which would adopt the Maine Plan, possibly in time for the 2008 Presidential Election.[23] Historically, the district system is viewed as the politically feasible alternative to direct elections because it removes the distortions of the winner-take-all system and can be enacted by state law rather than constitutional amendment. Quite often, support or opposition for the plan is based on the short-term partisan effects which would result from such an adoption.[24] However, the ultimate desirability of the district system lies in how it would change the conduct of presidential campaigns, not the counting of electoral college votes. Under the district system, presidential campaigns would shift their priorities from battleground states to battleground districts. The complexity and uncertainty in targeting these districts would force candidates to contest a larger and more geographically diverse percentage of the population than the system as it stood in 2004. Moreover, the changes in presidential campaigns would increase the likelihood of presidential coattails and the prospects for unified government by increasing the competitiveness of congressional elections in swing presidential districts. Finally, the district system has, at present, a Republican bias because the swing battleground districts favor Republican presidential candidates and have fewer minority and poor residents than the nation as a whole.[25]

Majority national vote

A proposal put forth in California in 2006 and under active consideration in other Democratic Party-controlled legislatures such as Maryland and Colorado in 2007, calls for a state that adopts the plan to give all its electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote, regardless of how the people of that state vote.[26] The plan would go into effect when enough states to comprise a majority of the Electoral College have ratified, and relies on the cooperation of those states. The California bill was vetoed by California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.[27] In Colorado the bill passed the state senate but not the house. Critics contend that it is unconstitutional (under Article 1 section 10 which prohibits any "compact" among states unless approved by Congress).

Proposals requiring Constitutional amendment

The most popular reform proposals are to simply abolish the Electoral College, and elect the president on the basis of a national popular vote. A constitutional amendment is needed. Such proposals differ in their details: some would elect the plurality winner of the popular vote, while others would require a minimum threshold to avoid a run-off (usually a 50%, or absolute majority threshold).

Additional proposals have included keeping the existing Electoral College, but changing the system by which elections are resolved if no candidate receives a majority in the Electoral College, or, separately, legally binding electors or eliminating electors while maintaining the vote counts produced by the Electoral College method.

Notes

- ↑ The term "electoral college" is not in the Constitution, which mentions only electors. It was first written into Federal law in 1845, and today the term appears in 3 U.S.C. section 4, in the section heading and in the text as "college of electors."

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 The Electoral College. Federal Election Commission (November 1992). Retrieved on 2007-04-29.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Historical Election Results: Electoral Votes for President and Vice President 1789-1821. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved on 2007-04-29.

- ↑ John Ferling, Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800 (2004) online pp 189-90

- ↑ Leon E. Aylsworth, "The Presidential Ballot," American Political Science Review 23, no. 1 (Feb. 1923), 89-96. in JSTOR

- ↑ The Electoral College: Enlightened Democracy. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved on 2007-05-01.

- ↑ Gaines (2001)

- ↑ 3 USC 7

- ↑ Images of the Certificates of Vote from the 2004 election can be seen at the National Archives.

- ↑ 3 USC 9-11

- ↑ Images of the Certificates of Ascertainment from the 2004 election can be seen at the National Archives.

- ↑ In 1988, for example, one West Virginia elector cast his presidential ballot for Lloyd Bentsen and his vice presidential ballot for Michael Dukakis, the reverse of the ticket. In 1976, a Washington elector cast his presidential ballot for Ronald Reagan instead of Gerald Ford.

- ↑ In 2004, one Minnesota elector voted for John Edwards on both the presidential and vice presidential ballots. And from time to time, votes go uncast - the last time was in 2000, when one District of Columbia elector failed to cast a ballot.

- ↑ Hill, David (2005). "The Electoral College, Mobilization, and Turnout in the 2000 Presidential Election.". American Politics Research 33(5): 700-725.

- ↑ for example, see Rakove (2004)

- ↑ Best (2004)

- ↑ Den Beste, Steven (2003-10-15). The Electoral College. Retrieved on 2007-05-02.

- ↑ Levinson et al (2007)

- ↑ Theodore H. White, In Search of History, pp. 490

- ↑ John J. Turner, , Jr. "One Vote for the Electoral College." History Teacher 2007 40(3): 411-416. Issn: 0018-2745 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ↑ Ornstein, (2001)

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions. FairVote (2006-03-05). Retrieved on 2007-05-06.

- ↑ Hiltachk, Thomas W. (July 17, 2007). Presidential Election Reform Act (PDF). California Secretary of State. Retrieved on 2007-08-14.

- ↑ for example, see a Democrat's response to the possibility of California adopting the Maine Plan, which would shift about 20 Electoral votes to the Republicans in the short term: Hertzberg, Hendrik (August 6, 2007). "Votescam". The New Yorker. Retrieved on 2007-08-13.

- ↑ Turner (2005)

- ↑ Stewart, Warren. California First To Pass Legislation To Establish National Popular Vote For President. VoteTrustUSA.

- ↑ AB 2948 Veto Message.