User:Pat Palmer/sandbox/test9: Difference between revisions

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) m (→Notes) Tag: Reverted |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

!!!Kahlil Gibran | |||

{{TOC|right}} | {{TOC|right}} | ||

parable of the sower | |||

Joan Acocella review | |||

{{Short description|Lebanese American artist, poet, and writer}} | |||

{{Redirect|Gibran|the name|Gebran (name)|other uses|Kahlil Gibran (disambiguation)}} | |||

{{Family name hatnote|Khalīl|Jubrān|lang=Lebanese}} | |||

{{Pp-move|reason=Repeatedly moved w/o consensus.|small=yes}} | |||

{{Use mdy dates|date=January 2022}} | |||

{{Use shortened footnotes|date=November 2020}} | |||

{{Infobox person | |||

| image = Kahlil Gibran 1913.jpg | |||

| imagesize = | |||

| caption = Gibran in 1913 | |||

| native_name = جُبْرَان خَلِيل جُبْرَان | |||

| native_name_lang = ar | |||

| birth_name = Gibran Khalil Gibran | |||

| birth_date = {{Birth date|1883|1|6|mf=y}} | |||

| birth_place = [[Bsharri]], [[Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate]], [[Ottoman Syria]], [[Ottoman Empire]] | |||

| death_date = {{death date and age|1931|4|10|1883|1|6|mf=y}} | |||

| death_place = New York City, United States | |||

| resting_place = Bsharri, modern-day Lebanon | |||

| nationality = Lebanese and American | |||

| alma_mater = [[Académie Julian]] | |||

| occupation = {{hlist|Writer|poet|visual artist|philosopher}} | |||

| known_for = Leading author of the [[Modern Arabic literature]] | |||

| style = {{hlist|[[Symbolism (arts)|Symbolic]]|[[prose poetry]]}} | |||

| title = Chairman of the [[Pen League]] | |||

| module = {{Infobox writer|embed=yes | |||

| pseudonym = | |||

| language = {{cslist|[[Varieties of Arabic]]|English}} | |||

| period = Modern ([[20th century in literature|20th century]]) | |||

| genres = {{hlist|Poem|[[parable]]|[[fable]]|[[aphorism]]|[[novel]]/[[novella]]|[[short story]]|[[play (theatre)|play]]|[[essay]]|[[letter (message)|letter]]}} | |||

| subjects = {{cslist|Spiritual love|justice}} | |||

| movement = {{cslist|[[Mahjar]]|[[neo-romanticism]]|[[symbolism (arts)|symbolism]]}} | |||

| years_active = from 1904 | |||

| notable_works = ''[[The Prophet (book)|The Prophet]]''; ''[[The Madman (book)|The Madman]]''; ''[[Broken Wings (Gibran novel)|Broken Wings]]''}} | |||

| awards = | |||

| signature = Collage Gibran signatures.png | |||

}} | |||

'''Gibran Khalil Gibran''' (January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931), usually referred to in English as '''Kahlil Gibran'''{{efn|Due to a mistake made by the Josiah Quincy School of Boston after his immigration to the United States with his mother and siblings {{see below|{{sectionlink||Life}}}}, he was registered as K''ah''lil Gibran, the spelling he used thenceforth in English.<ref name="Gibran 1991, p. 29">{{harvnb|Gibran|Gibran|1991|p=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranhisl00gibr/page/29/mode/1up 29]}}</ref> Other sources use K''ha''lil Gibran, reflecting the typical English spelling of the forename [[Khalil (given name)|Khalil]], although Gibran continued to use his full birth name for publications in Arabic.}} (<small>pronounced</small> {{IPAc-en|k|ɑː|ˈ|l|iː|l|_|dʒ|ɪ|ˈ|b|r|ɑː|n}} {{respell|kah|LEEL|_|ji|BRAHN}}),{{sfn |''dictionary.com'' |2012}} was a Lebanese-American writer, poet and [[Visual arts|visual artist]]; he was also considered a philosopher, although he himself rejected the title.<ref>{{harvnb|Moussa|2006|p=207}}; {{harvnb|Kairouz|1995|p=107}}.</ref> He is best known as the author of ''[[The Prophet (book)|The Prophet]]'', which was first published in the United States in 1923 and has since become one of the [[List of best-selling books|best-selling books]] of all time, having been [[Translations of The Prophet|translated into more than 100 languages]].{{efn|Gibran is also considered to be the third-best-selling poet of all time, behind [[William Shakespeare|Shakespeare]] and [[Laozi]].{{sfn|Acocella|2007}}}} | |||

Born in [[Bsharri]], a village of the Ottoman-ruled [[Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate]] to a [[Maronites|Maronite Christian]] family, young Gibran immigrated with his mother and siblings to the United States in 1895. As his mother worked as a seamstress, he was enrolled at a school in [[Boston]], where his creative abilities were quickly noticed by a teacher who presented him to photographer and publisher [[F. Holland Day]]. Gibran was sent back to his native land by his family at the age of fifteen to enroll at the [[Collège de la Sagesse]] in [[Beirut]]. Returning to Boston upon his youngest sister's death in 1902, he lost his older half-brother and his mother the following year, seemingly relying afterwards on his remaining sister's income from her work at a dressmaker's shop for some time. | |||

In 1904, Gibran's drawings were displayed for the first time at Day's studio in Boston, and his first book in Arabic was published in 1905 in [[New York City]]. <ref>{{Cite web |title=Gibran National Committee - Biography |url=http://www.gibrankhalilgibran.org/AboutGebran/Biography/ |access-date=2023-08-02 |website=www.gibrankhalilgibran.org}}</ref> With the financial help of a newly met benefactress, [[Mary Haskell (educator)|Mary Haskell]], Gibran studied art in [[Paris]] from 1908 to 1910. While there, he came in contact with Syrian political thinkers promoting rebellion in Ottoman Syria after the [[Young Turk Revolution]];<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5"/> some of Gibran's writings, voicing the same ideas as well as [[anti-clericalism]],<ref name="Bashshur McCarus Yacoub 1963 p. 229">{{harvnb |Bashshur |McCarus |Yacoub |1963 |p=229}}{{volume needed|issue=no|date=November 2020}}</ref> would eventually be banned by the Ottoman authorities.<ref name="Bushrui & Jenkins 1998">{{harvnb|Bushrui|Jenkins|1998}}{{Page needed|date=November 2020}}</ref> In 1911, Gibran settled in New York, where his first book in English, ''[[The Madman (book)|The Madman]]'', was published by [[Alfred A. Knopf]] in 1918, with writing of ''The Prophet'' or ''[[The Earth Gods]]'' also underway.{{sfn|Juni|2000|p=[{{Google books|RRNeMZRy_wAC|page=8|plainurl=yes}} 8]}} His visual artwork was shown at Montross Gallery in 1914,{{sfn |Montross Gallery |1914}} and at the galleries of [[Knoedler|M. Knoedler & Co.]] in 1917. He had also been corresponding remarkably with [[May Ziadeh]] since 1912.<ref name="Bushrui & Jenkins 1998"/> In 1920, Gibran re-founded the [[Pen League]] with fellow [[Mahjar]]i poets. By the time of his death at the age of 48 from [[cirrhosis]] and incipient [[tuberculosis]] in one lung, he had achieved literary fame on "both sides of the Atlantic Ocean",{{sfn |Arab Information Center |1955 |p=11}} and ''The Prophet'' had already been translated into German and French. His body was transferred to his birth village of [[Bsharri]] (in present-day Lebanon), to which he had bequeathed all future royalties on his books, and where a [[Gibran Museum|museum]] dedicated to his works now stands. | |||

In the words of [[Suheil Bushrui]] and Joe Jenkins, Gibran's life was "often caught between [[Friedrich Nietzsche|Nietzschean]] rebellion, [[William Blake|Blakean]] [[pantheism]] and [[Sufism|Sufi]] [[mysticism]]."<ref name="Bushrui & Jenkins 1998"/> Gibran discussed different themes in his writings and explored diverse literary forms. [[Salma Khadra Jayyusi]] has called him "the single most important influence on [[Arabic poetry]] and [[Arabic literature|literature]] during the first half of [the twentieth] century,"{{sfn|Jayyusi|1987|p=[https://archive.org/details/modernarabicpoet0000unse/page/4/mode/1up 4]}} and he is still celebrated as a literary hero in Lebanon.{{sfn |Amirani |Hegarty |2012}} At the same time, "most of Gibran's paintings expressed his personal vision, incorporating spiritual and mythological symbolism,"{{sfn |Oweis |2008 |p=[{{Google books |id=dEZC4g_j62gC |page=136 |plainurl=yes}} 136]}} with art critic Alice Raphael recognizing in the painter a [[Classicism|classicist]], whose work owed "more to the findings of [[Leonardo da Vinci|Da Vinci]] than it [did] to any modern insurgent."<ref>{{harvnb|Ghougassian|1973|p=51}}.</ref> His "prodigious body of work" has been described as "an artistic legacy to people of all nations".{{sfn |Oakar |1984 |pp=[{{Google books |id=PdQvAAAAIAAJ |pg=RA8-PP7 |plainurl=yes}} 1–3]}} | |||

{{toc limit|3}} | |||

==Life== | |||

===Childhood=== | |||

{{Multiple image|image1=Khalil Gibran Family.jpg|total_width=350|caption1=The Gibran family in the 1880s{{efn|Left to right: Gibran, Khalil (father), Sultana (sister), Boutros (half-brother), Kamila (mother).}}|image2=gibranshome.jpg|caption2=The Gibran family's home in [[Bsharri]], Lebanon}} | |||

Gibran was born January 6, 1883, in the village of [[Bsharri]] in the [[Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate]], Ottoman Syria (modern-day [[Lebanon]]).<ref name="Waterfield 1998, chapter 1">{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 1}}.</ref> His parents, Khalil Sa'ad Gibran<ref name="Waterfield 1998, chapter 1"/> and Kamila Rahmeh, the daughter of a priest, were [[Maronite Church|Maronite]] Christian. As written by Bushrui and Jenkins, they would set for Gibran an example of tolerance by "refusing to perpetuate religious prejudice and bigotry in their daily lives."<ref name="Bushrui 55"/> Kamila's paternal grandfather had converted from Islam to Christianity.<ref name="Gibran, Gibran & Hayek 2017"/><ref>{{harvnb|Chandler|2017|page=18}}</ref> She was thirty when Gibran was born, and Gibran's father, Khalil, was her third husband.{{sfn |''Gibran: Birth and Childhood''}} Gibran had two younger sisters, Marianna and Sultana, and an older half-brother, Boutros, from one of Kamila's previous marriages. Gibran's family lived in poverty. In 1888, Gibran entered Bsharri's one-class school, which was run by a priest, and there he learnt the rudiments of Arabic, [[Syriac language|Syriac]], and arithmetic.{{efn|According to [[Khalil Gibran (sculptor)|Khalil]] and Jean Gibran, this did not count as "formal" schooling.<ref name="Gibran, Gibran & Hayek 2017">{{harvnb |Gibran |Gibran |Hayek |2017 |p=}}{{page needed|date=November 2020}}</ref>}}<ref name="Gibran, Gibran & Hayek 2017"/><ref>{{harvnb|Naimy|1985b|p=93}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Karam|1981|p=20}}</ref> | |||

Gibran's father initially worked in an [[apothecary]], but he had gambling debts he was unable to pay. He went to work for a local Ottoman-appointed administrator.{{sfn |Cole |2000}}{{sfn |Waldbridge |1998}} In 1891, while acting as a tax collector, he was removed and his staff was investigated.{{sfn |Mcharek |2006}} Khalil was imprisoned for embezzlement,{{sfn|Acocella|2007}} and his family's property was confiscated by the authorities. Kamila decided to follow her brother to the United States. Although Khalil was released in 1894, Kamila remained resolved and left for New York on June 25, 1895, taking Boutros, Gibran, Marianna and Sultana with her.{{sfn |Cole |2000}} | |||

[[File:-F. Holland Day- MET DP264342.jpg|thumb|125px|left|[[F. Holland Day]], {{circa}} 1898]] | |||

[[Image:Khali Gibran.jpg|thumb|right|Photograph of Gibran by F. Holland Day, {{circa|1898}}]] | |||

Kamila and her children settled in Boston's [[South End, Boston|South End]], at the time the second-largest Syrian-Lebanese-American community{{sfn |Middle East & Islamic Studies}} in the United States. Gibran entered the Josiah Quincy School on September 30, 1895. School officials placed him in a special class for immigrants to learn English. His name was registered using the anglicized spelling 'Ka''h''lil Gibran'.<ref name="Gibran 1991, p. 29"/>{{sfn |Medici |2019}} His mother began working as a seamstress{{sfn |Mcharek |2006}} peddler, selling lace and linens that she carried from door-to-door. His half-brother Boutros opened a shop. Gibran also enrolled in an art school at [[Denison House (Boston)|Denison House]], a nearby [[Settlement movement|settlement house]]. Through his teachers there, he was introduced to the [[avant-garde]] Boston artist, photographer and publisher [[F. Holland Day]],{{sfn|Acocella|2007}} who encouraged and supported Gibran in his creative endeavors. In March 1898, Gibran met [[Josephine Preston Peabody]], eight years his senior, at an exhibition of Day's photographs "in which Gibran's face was a major subject."<ref>{{harvnb|Kairouz|1995|p=24}}.</ref> Gibran would develop a romantic attachment to her.{{sfn |Rosenzweig |1999 |pp=[{{Google books |id=WoPsjMVBleoC |page=157 |plainurl=yes}} 157–158]}} The same year, a publisher used some of Gibran's drawings for book covers. | |||

[[File:Le Jubilé épiscopal de Mgr (...)Saint-Ouen Th bpt6k5611424t.jpg|thumb|left|upright|The [[Collège de la Sagesse|Collège maronite de la Sagesse]] in [[Beirut]]]] | |||

Kamila and Boutros wanted Gibran to absorb more of his own heritage rather than just the Western aesthetic culture he was attracted to.{{sfn |Mcharek |2006}} Thus, at the age of 15, Gibran returned to his homeland to study [[Arabic literature]] for three years at the [[Collège de la Sagesse]], a Maronite-run institute in [[Beirut]], also learning French.<ref>{{harvnb|Corm|2004|p=121}}</ref>{{efn|American journalist [[Alma Reed]] would relate that Gibran spoke French fluently, besides Arabic and English.<ref>{{harvnb|Reed|1956|p=103}}</ref>}} In his final year at the school, Gibran created a student magazine with other students, including [[Youssef Howayek]] (who would remain a lifelong friend of his),<ref name="Waterfield chapter 3">{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 3}}.</ref> and he was made the "college poet".<ref name="Waterfield chapter 3"/> Gibran graduated from the school at eighteen with high honors, then went to Paris to learn painting, visiting Greece, Italy, and Spain on his way there from Beirut.<ref>{{harvnb|Ghougassian|1973|p=26}}.</ref> On April 2, 1902, Sultana died at the age of 14, from what is believed to have been [[tuberculosis]].<ref name="Waterfield chapter 3"/> Upon learning about it, Gibran returned to Boston, arriving two weeks after Sultana's death.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 3"/>{{efn|He came through [[Ellis Island]] (this was his second time) on May 10.{{sfn |''Ship manifest, Saint Paul, arriving at New York'' |1902}}}} The following year, on March 12, Boutros died of the same disease, with his mother passing from cancer on June 28.<ref name="Daoudi 1982, p. 28">{{harvnb|Daoudi|1982|p=[https://archive.org/details/meaningofkahlilg0000daou/page/28/mode/1up 28]}}.</ref> Two days later, Peabody "left him without explanation."<ref name="Daoudi 1982, p. 28"/> Marianna supported Gibran and herself by working at a dressmaker's shop.{{sfn|Acocella|2007}} | |||

{{ | ===Debuts, Mary Haskell, and second stay in Paris=== | ||

[[File:Mary Haskell by Kahlil Gibran.jpg|thumb|150px|Portrait of [[Mary Haskell (educator)|Mary Haskell]] by Gibran, 1910]] | |||

Gibran held the first art exhibition of his drawings in January 1904 in Boston at Day's studio.{{sfn|Acocella|2007}} During this exhibition, Gibran met [[Mary Haskell (educator)|Mary Haskell]], the headmistress of a girls' school in the city, nine years his senior. The two formed a friendship that lasted the rest of Gibran's life. Haskell would spend large sums of money to support Gibran and would also edit all of his English writings. The nature of their romantic relationship remains obscure; while some biographers assert the two were lovers<ref>{{harvnb|Otto|1970}}.</ref> but never married because Haskell's family objected,{{sfn |Amirani |Hegarty |2012}} other evidence suggests that their relationship was never physically consummated.{{sfn|Acocella|2007}} Gibran and Haskell were engaged briefly between 1910 and 1911.{{sfn |McCullough |2005 |p=184}} According to Joseph P. Ghougassian, Gibran had proposed to her "not knowing how to repay back in gratitude to Miss Haskell," but Haskell called it off, making it "clear to him that she preferred his friendship to any burdensome tie of marriage."<ref name="Ghougassian 1973 30">{{harvnb|Ghougassian|1973|p=30}}.</ref> Haskell would later marry Jacob Florance Minis in 1926, while remaining Gibran's close friend, patroness and benefactress, and using her influence to advance his career.{{sfn|Najjar|2008|pp=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranauth0000najj/page/79/mode/2up 79–84]}} | |||

| | |||

{{Multiple image|align=left|total_width=250|image1=Portrait of Charlotte Teller by Kahlil Gibran.jpg|caption1=''Portrait of Charlotte Teller'', {{circa}} 1911|image2=Emilie Michel's portrait, Micheline by Khalil Gibran - Soumaya.jpg|caption2=''Portrait of Émilie Michel (Micheline)'', 1909}} | |||

It was in 1904 also that Gibran met Amin al-Ghurayyib, editor of ''Al-Mohajer'' ('The Emigrant'), where Gibran started to publish articles.{{sfn|Moss|2004|p=65}} In 1905, Gibran's first published written work was ''A Profile of the Art of Music'', in Arabic, by ''Al-Mohajer''{{'}}s printing department in New York City. His next work, ''Nymphs of the Valley'', was published the following year, also in Arabic. On January 27, 1908, Haskell introduced Gibran to her friend writer [[Charlotte Teller]], aged 31, and in February, to Émilie Michel (Micheline), a French teacher at Haskell's school,<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5">{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 5}}.</ref> aged 19. Both Teller and Micheline agreed to pose for Gibran as models and became close friends of his.{{sfn|Najjar|2008|pp=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranauth0000najj/page/59/mode/2up 59–60]}} The same year, Gibran published ''Spirits Rebellious'' in Arabic, a novel deeply critical of secular and spiritual authority.{{sfn |Ghougassian |1974 |pp=[https://archive.org/details/thirdtreasuryofk0000sher/page/212/mode/2up 212–213]}} According to [[Barbara Young (poet)|Barbara Young]], a late acquaintance of Gibran, "in an incredibly short time it was burned in the market place in Beirut by priestly zealots who pronounced it 'dangerous, revolutionary, and poisonous to youth.{{' "}}<ref>{{harvnb|Young|1945|p=19}}.</ref> The Maronite Patriarchate would let the rumor of his excommunication wander, but would never officially pronounce it.<ref>{{harvnb|Dahdah|1994|p=215}}.</ref> | |||

[[File:Plaque Gibran Khalil Gibran, 14 avenue du Maine, Paris 15e.jpg|thumb|upright|Plaque at 14 [[Avenue du Maine]], Paris, where Gibran lived from 1908 to 1910]] | |||

In July 1908, with Haskell's financial support, Gibran went to study art in Paris at the [[Académie Julian]] where he joined the ''atelier'' of [[Jean-Paul Laurens]].<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5"/> Gibran had accepted Haskell's offer partly so as to distance himself from Micheline, "for he knew that this love was contrary to his sense of gratefulness toward Miss Haskell"; however, "to his surprise Micheline came unexpectedly to him in Paris."<ref name="Ghougassian 1973, p. 29">{{harvnb|Ghougassian|1973|p=29}}.</ref> "She became pregnant, but the pregnancy was [[Ectopic pregnancy|ectopic]], and she had to have an abortion, probably in France."<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5"/> Micheline had returned to the United States by late October.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5"/> Gibran would pay her a visit upon her return to Paris in July 1910, but there would be no hint of intimacy left between them.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5"/> | |||

By early February 1909, Gibran had "been working for a few weeks in the studio of [[Pierre Marcel-Béronneau]]",<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5" /> and he "used his sympathy towards Béronneau as an excuse to leave the Académie Julian altogether."<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5" /> In December 1909,{{efn|Gibran's father had died in June.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5"/>}} Gibran started a series of pencil portraits that he would later call "The Temple of Art", featuring "famous men and women artists of the day" and "a few of Gibran's heroes from past times."<ref name="Waterfield chapter 6" />{{efn|name=Temple of Art|Included in the Temple of Art series are portraits of [[Paul Wayland Bartlett|Paul Bartlett]], [[Claude Debussy]], [[Edmond Rostand]], [[Henri Rochefort]], [[W. B. Yeats]], [[Carl Jung]], and [[Auguste Rodin]].<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5"/>{{sfn |Amirani |Hegarty |2012}} Gibran reportedly met the latter on a couple of occasions during his Parisian stay to draw his portrait; however, Gibran biographer [[Robin Waterfield]] argues that "on neither occasion was any degree of intimacy attained", and that the portrait may well have been made from memory or from a photograph.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5"/> Gibran met Yeats through a friend of Haskell in Boston in September 1911, drawing his portrait on October 1 of that year.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 6"/>}} While in Paris, Gibran also entered into contact with Syrian political dissidents, in whose activities he would attempt to be more involved upon his return to the United States.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5" /> In June 1910, Gibran visited London with Howayek and [[Ameen Rihani]], whom Gibran had met in Paris.<ref>{{harvnb|Larangé|2005|p=180}}; {{harvnb|Hajjar|2010|p=28}}.</ref> Rihani, who was six years older than Gibran, would be Gibran's role model for a while, and a friend until at least May 1912.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 8">{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 8}}.</ref>{{efn|Gibran would illustrate Rihani's ''[[Book of Khalid]]'', published 1911.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 6">{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 6}}.</ref>}} Gibran biographer [[Robin Waterfield]] argues that, by 1918, "as Gibran's role changed from that of angry young man to that of prophet, Rihani could no longer act as a paradigm".<ref name="Waterfield chapter 8" /> Haskell (in her private journal entry of May 29, 1924) and Howayek also provided hints at an enmity that began between Gibran and Rihani sometime after May 1912.<ref>{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 8 (notes 28 & 29)}}.</ref> | |||

{{ | ===Return to the United States and growing reputation=== | ||

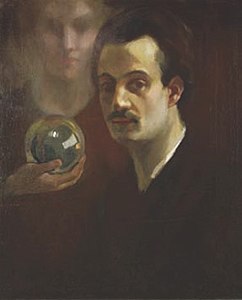

| | {{Multiple image|total_width=350|image1=Self Portrait by Kahlil Gibran.jpg|caption1=''Self-Portrait'', {{circa|1911}}|image2=Studios, 51 West Tenth Street, Manhattan (NYPL b13668355-482793) (cropped).jpg|caption2=The [[Tenth Street Studio Building]] in New York City (photographed 1938)}} | ||

Gibran sailed back to New York City from [[Boulogne-sur-Mer]] on the [[SS Nieuw Amsterdam (1905)|''Nieuw Amsterdam'']] on October 22, 1910, and was back in Boston by November 11.<ref name="Ghougassian 1973 30"/> By February 1911, Gibran had joined the Boston branch of a Syrian international organization, the Golden Links Society.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 8"/>{{efn|{{lang-ar|الحلقات الذهبية}}, {{ALA-LC|ar|al-Ḥalaqāt al-Dhahabiyyah}}. As worded by Waterfield, "the ostensible purpose of the society was the improvement of life for Syrians all around the world—which included their homeland, where improvement of life could mean taking a stand on Ottoman rule."<ref name="Waterfield chapter 8"/>}} He lectured there for several months "in order to promote radicalism in independence and liberty" from Ottoman Syria.<ref>{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 8}}; {{harvnb|Kairouz|1995|p=33}}.</ref> At the end of April, Gibran was staying in Teller's vacant flat at 164 [[Waverly Place]] in New York City.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 6"/> "Gibran settled in, made himself known to his Syrian friends—especially Amin Rihani, who was now living in New York—and began both to look for a suitable studio and to sample the energy of New York."<ref name="Waterfield chapter 6"/> As Teller returned on May 15, he moved to Rihani's small room at 28 West 9th Street.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 6"/>{{efn|By June 1, Gibran had introduced Rihani to Teller.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 6"/> A relationship would develop between Rihani and Teller, lasting for a number of months.<ref name="Bushrui & Jenkins 1998"/>}} Gibran then moved to one of the [[Tenth Street Studio Building]]'s studios for the summer, before changing to another of its studios (number 30, which had a balcony, on the third story) in fall.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 6"/> Gibran would live there until his death,{{sfn |Kates |2019}}{{Better source needed|reason=This source is a blog and may violate the [[WP:SELFPUBLISH]] policy.|date=November 2020}} referring to it as "The Hermitage."<ref name="Daoudi 1982, p. 30">{{harvnb|Daoudi|1982|p=[https://archive.org/details/meaningofkahlilg0000daou/page/30/mode/1up 30]}}.</ref> Over time, however, and "ostensibly often for reasons of health," he would spend "longer and longer periods away from New York, sometimes months at a time [...], staying either with friends in the countryside or with Marianna in Boston or on the [[Massachusetts]] coast."<ref name="Waterfield 1998 loc=chapter 11">{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 11}}.</ref> His friendships with Teller and Micheline would wane; the last encounter between Gibran and Teller would occur in September 1912, and Gibran would tell Haskell in 1914 that he now found Micheline "repellent."<ref name="Waterfield chapter 8"/>{{efn|Teller married writer Gilbert Julius Hirsch (1886–1926) on October 14, 1912, with whom she lived periodically in New York and in different parts of Europe,<ref name="Otto">{{harvnb|Otto|1970|loc=Preface}}.</ref> dying in 1953. Micheline married a New York City attorney, Lamar Hardy, on October 14, 1914.<ref name="Otto"/>}} | |||

[[File:May Ziadeh.jpg|thumb|150px|left|[[May Ziadeh]]]] | |||

In 1912, the poetic [[novella]] ''[[Broken Wings (Gibran novel)|Broken Wings]]'' was published in Arabic by the printing house of the periodical ''[[Meraat-ul-Gharb]]'' in New York. Gibran presented a copy of his book to Lebanese writer [[May Ziadeh]], who lived in Egypt, and asked her to criticize it.{{sfn |Gibran |1959 |p=[https://archive.org/details/isbn_9782866005276/page/38/mode/1up?q=Broken+Wings 38]}} As worded by Ghougassian, | |||

{{blockquote|Her reply on May 12, 1912, did not totally approve of Gibran's philosophy of love. Rather she remained in all her correspondence quite critical of a few of Gibran's Westernized ideas. Still he had a strong emotional attachment to Miss Ziadeh till his death.<ref>{{harvnb|Ghougassian|1973|p=31}}.</ref>}} | |||

Gibran and Ziadeh never met.<ref>{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 7.}}</ref> According to [[Shlomit C. Schuster]], "whatever the relationship between Kahlil and May might have been, the letters in ''A Self-Portrait'' mainly reveal their literary ties.{{sfn |Gibran |1959 |pp=}} Ziadeh reviewed all of Gibran's books and Gibran replies to these reviews elegantly."<ref>{{harvnb|Schuster|2003|p=38}}.</ref> | |||

{{quote box|width=25%|quote=Poet, who has heard thee but the spirits that follow thy solitary path?<br>Prophet, who has known thee but those who are driven by the Great Tempest to thy lonely grove?|source=''To Albert Pinkham Ryder'' (1915), first two verses}} | |||

In 1913, Gibran started contributing to ''[[Al-Funoon]]'', an Arabic-language magazine that had been recently established by [[Nasib Arida]] and [[Abd al-Masih Haddad]]. ''A Tear and a Smile'' was published in Arabic in 1914. In December of the same year, visual artworks by Gibran were shown at the Montross Gallery, catching the attention of American painter [[Albert Pinkham Ryder]]. Gibran wrote him a prose poem in January and would become one of the aged man's last visitors.<ref>{{harvnb |Ryan |Shengold |1994 |p=197}}; {{harvnb|Otto|1970|p=404}}; {{harvnb|Bushrui|Jenkins|1998}}{{Page needed|date=November 2020}}</ref> After Ryder's death in 1917, Gibran's poem would be quoted first by [[Henry McBride (art critic)|Henry McBride]] in the latter's posthumous tribute to Ryder, then by newspapers across the country, from which would come the first widespread mention of Gibran's name in America.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 9">{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 9}}.</ref> By March 1915, two of Gibran's poems had also been read at the [[Poetry Society of America]], after which [[Corinne Roosevelt Robinson]], the younger sister of [[Theodore Roosevelt]], stood up and called them "destructive and diabolical stuff";<ref>{{harvnb|Bushrui|Jenkins|1998}}{{Page needed|date=November 2020}}; {{harvnb|Otto|1970|p=404}}.</ref> nevertheless, beginning in 1918 Gibran would become a frequent visitor at Robinson's, also meeting her brother.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 8"/> | |||

===''The Madman'', the Pen League, and ''The Prophet''=== | |||

Gibran acted as a secretary of the [[Syrian–Mount Lebanon Relief Committee]], which was formed in June 1916.{{sfn|Beshara|2012|p=[{{Google books|nr9Ivt-pc0IC|page=147|plainurl=yes}} 147]}}{{sfn|Majāʻiṣ|2004|p=107}} The same year, Gibran met Lebanese author [[Mikhail Naimy]] after Naimy had moved from the [[University of Washington]] to New York.{{sfn |Haiek |2003 |p=134}}{{sfn|Naimy|1985b|p=67}} Naimy, whom Gibran would nickname "Mischa,"<ref>{{harvnb|Bushrui|Munro|1970|p=72}}.</ref> had previously made a review of ''Broken Wings'' in his article "The Dawn of Hope After the Night of Despair", published in ''Al-Funoon'',{{sfn |Haiek |2003 |p=134}} and he would become "a close friend and confidant, and later one of Gibran's biographers."<ref>{{harvnb|Bushrui|1987|p=40}}.</ref> In 1917, an exhibition of forty wash drawings was held at [[Knoedler]] in New York from January 29 to February 19 and another of thirty such drawings at Doll & Richards, Boston, April 16–28.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 9"/> | |||

[[File:Algunos miembros de Al-Rabita al-Qalamiyya.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Four members of the [[Pen League]] in 1920. Left to right: [[Nasib Arida]], Gibran, [[Abd al-Masih Haddad]], and [[Mikhail Naimy]]]] | |||

While most of Gibran's early writings had been in Arabic, most of his work published after 1918 was in English. Such was ''[[The Madman (book)|The Madman]]'', Gibran's first book published by [[Alfred A. Knopf]] in 1918. ''The Processions'' (in Arabic) and ''Twenty Drawings'' were published the following year. In 1920, Gibran re-created the Arabic-language [[New York Pen League]] with Arida and Haddad (its original founders), Rihani, Naimy, and other [[Mahjar]]i writers such as [[Elia Abu Madi]]. The same year, ''The Tempests'' was published in Arabic in Cairo,<ref>{{harvnb|Naimy|1985b|p=95}}</ref> and ''The Forerunner'' in New York.{{sfn|Gibran|Gibran|1991|p=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranhisl00gibr/page/446/mode/1up 446]}} | |||

{| | In a letter of 1921 to Naimy, Gibran reported that doctors had told him to "give up all kinds of work and exertion for six months, and do nothing but eat, drink and rest";{{sfn|Naimy|1985a|p=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranbiog00nuay/page/252/mode/2up 252]}} in 1922, Gibran was ordered to "stay away from cities and city life" and had rented a cottage near the sea, planning to move there with Marianna and to remain until "this heart [regained] its orderly course";{{sfn|Naimy|1985a|p=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranbiog00nuay/page/254/mode/2up 254]}} this three-month summer in [[Scituate, Massachusetts|Scituate]], he later told Haskell, was a refreshing time, during which he wrote some of "the best Arabic poems" he had ever written.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 11 note 38">{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 11, note 38}}.</ref> | ||

| | |||

|< | |||

The | [[File:The Prophet (Gibran).jpg|thumb|upright|First edition cover of ''[[The Prophet (book)|The Prophet]]'' (1923)]] | ||

In 1923, ''The New and the Marvelous'' was published in Arabic in Cairo, whereas ''[[The Prophet (book)|The Prophet]]'' was published in New York. ''The Prophet'' sold well despite a cool critical reception.{{efn|It would gain popularity in the 1930s and again especially in the [[Counterculture of the 1960s|1960s counterculture]].{{sfn |Amirani |Hegarty |2012}}{{sfn|Acocella|2007}}}} At a reading of ''The Prophet'' organized by rector [[William Norman Guthrie]] in [[St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery]], Gibran met poet [[Barbara Young (poet)|Barbara Young]], who would occasionally work as his secretary from 1925 until Gibran's death; Young did this work without remuneration.<ref>{{harvnb|Ghougassian|1973|p=32}}.</ref> In 1924, Gibran told Haskell that he had been contracted to write ten pieces for ''[[Al-Hilal (magazine)|Al-Hilal]]'' in Cairo.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 11 note 38"/> In 1925, Gibran participated in the founding of the periodical ''The New East''.<ref>{{harvnb|Kairouz|1995|p=42}}.</ref> | |||

===Later years and death=== | |||

[[File:Kahlil Gibran 1.jpg|thumb|left|A late photograph of Gibran]] | |||

''Sand and Foam'' was published in 1926, and ''Jesus, the Son of Man'' in 1928. At the beginning of 1929, Gibran was diagnosed with an [[enlarged liver]].<ref name="Waterfield 1998 loc=chapter 11"/> In a letter dated March 26, he wrote to Naimy that "the rheumatic pains are gone, and the swelling has turned to something opposite".{{sfn|Naimy|1985a|p=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranbiog00nuay/page/260/mode/2up 260]}} In a telegram dated the same day, he reported being told by the doctors that he "must not work for full year," which was something he found "more painful than illness."{{sfn|Naimy|1985a|p=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranbiog00nuay/page/260/mode/2up 261]}} The last book published during Gibran's life was ''[[The Earth Gods]]'', on March 14, 1931. | |||

Gibran was admitted to [[St. Vincent's Hospital, Manhattan]], on April 10, 1931, where he died the same day, aged forty-eight, after refusing the [[last rites]].{{sfn|Gibran|Gibran|1991|p=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranhisl00gibr/page/432/mode/1up?q=St.+Vincent%27s+Hospital 432]}} The cause of death was reported to be [[cirrhosis]] of the liver with incipient [[tuberculosis]] in one of his lungs.<ref name="Daoudi 1982, p. 30"/> Waterfield argues that the cirrhosis was contracted through excessive drinking of alcohol and was the only real cause of Gibran's death.<ref>{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 12}}.</ref> | |||

[[File:Gibran Museum.JPG|thumb|upright|The [[Gibran Museum]] and Gibran's final resting place, in Bsharri]] | |||

{{Quote box | {{Quote box|align=right|width=175px|quote="The epitaph I wish to be written on my tomb:<br>'I am alive, like you. And I now stand beside you. Close your eyes and look around, you will see me in front of you'. Gibran"|source=Epitaph at the Gibran Museum<ref>{{harvnb|Kairouz|1995|p=104}}.</ref> | ||

| | |||

|quote = | |||

|source = | |||

| | |||

}} | }} | ||

Gibran had expressed the wish that he be buried in Lebanon. His body lay temporarily at Mount Benedict Cemetery in Boston before it was taken on July 23 to [[Providence, Rhode Island]], and from there to Lebanon on the liner ''[[SS Sinaia|Sinaia]]''.<ref>{{harvnb|Kairouz|1995|p=46}}.</ref> Gibran's body reached Bsharri in August and was deposited in a church near-by until a cousin of Gibran finalized the purchase of the Mar Sarkis Monastery, now the [[Gibran Museum]].{{sfn |Medici |Samaha |2019}} | |||

All future American royalties to his books were willed to his hometown of [[Bsharri]], to be used for "civic betterment."<ref name="Daoudi 1982, p. 32">{{harvnb|Daoudi|1982|p=[https://archive.org/details/meaningofkahlilg0000daou/page/32/mode/1up 32]}}.</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Turner|1971|p=55}}</ref> Gibran had also willed the contents of his studio to Haskell.<ref name="Daoudi 1982, p. 32"/> | |||

{{blockquote|Going through his papers, Young and Haskell discovered that Gibran had kept all of Mary's love letters to him. Young admitted to being stunned at the depth of the relationship, which was all but unknown to her. In her own biography of Gibran, she minimized the relationship and begged Mary Haskell to burn the letters. Mary agreed initially but then reneged, and eventually they were published, along with her journal and Gibran's some three hundred letters to her, in [Virginia] Hilu's ''Beloved Prophet''.{{sfn |Jason |2003 |p=1415}}}} | |||

[[ | In 1950, Haskell donated her personal collection of nearly one hundred original works of art by Gibran (including five oils) to the [[Telfair Museum of Art]] in [[Savannah, Georgia]].{{sfn |McCullough |2005 |p=184}} Haskell had been thinking of placing her collection at the Telfair as early as 1914.{{sfn |McCullough |2005 |pp=184–185}}{{efn|In a letter to Gibran, she wrote: | ||

{{blockquote|I am thinking of other museums ... the unique little Telfair Gallery in Savannah, Ga., that [[Gari Melchers]] chooses pictures for. There when I was a visiting child, form burst upon my astonished little soul.{{sfn |McCullough |2005 |p=185}}}}}} Her gift to the Telfair is the largest public collection of Gibran's visual art in the country. | |||

==Works== | |||

===Writings=== | |||

{{See also|List of works by Kahlil Gibran#Writings}} | |||

'' | ====Forms, themes, and language==== | ||

Gibran explored literary forms as diverse as "poetry, [[parable]]s, fragments of conversation, [[Short story|short stories]], [[fable]]s, political [[essay]]s, letters, and [[aphorism]]s."{{sfn |Jason |2003 |p=1413}} Two [[Play (theatre)|plays]] in English and five plays in Arabic were also published posthumously between 1973 and 1993; three unfinished plays written in English towards the end of Gibran's life remain unpublished (''The Banshee'', ''The Last Unction'', and ''The Hunchback or the Man Unseen'').<ref>{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 11, note 83}}.</ref> Gibran discussed "such themes as religion, justice, free will, science, love, happiness, the soul, the body, and death"<ref>{{harvnb|Moreh|1988|p=141}}.</ref> in his writings, which were "characterized by innovation breaking with forms of the past, by [[Symbolism (arts)|symbolism]], an undying love for his native land, and a sentimental, melancholic yet often oratorical style."<ref name="Bashshur McCarus Yacoub 1963">{{harvnb |Bashshur |McCarus |Yacoub |1963 |p=}}{{volume needed|issue=no|date=November 2020}}{{page needed|date=November 2020}}</ref> According to [[Salma Jayyusi]], [[Roger Allen (translator)|Roger Allen]] and others, Gibran as the leading poet of the [[Mahjar]] school belongs to [[Romantic poetry|Romantic]] ([[neo-romanticism|neo-romantic]]) movement.{{sfn|Jayyusi|1977|pp=361–362}}{{sfn|Allen|2012|pp=69–70}} | |||

About his language in general (both in Arabic and English), [[Salma Khadra Jayyusi]] remarks that "because of the spiritual and universal aspect of his general themes, he seems to have chosen a vocabulary less idiomatic than would normally have been chosen by a modern poet conscious of modernism in language."{{sfn |Jayyusi |Tingley |1977 |p=101}} According to Jean Gibran and [[Kahlil Gibran (sculptor)|Kahlil G. Gibran]], | |||

{{blockquote|Ignoring much of the traditional vocabulary and form of [[classical Arabic]], he began to develop a style which reflected the ordinary language he had heard as a child in Besharri and to which he was still exposed in the South End [of Boston]. This use of the colloquial was more a product of his isolation than of a specific intent, but it appealed to thousands of Arab immigrants.<ref>{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 5 (quoting Gibran & Gibran)}}.</ref>}} | |||

The poem "You Have Your Language and I Have Mine" (1924) was published in response to criticism of his Arabic language and style.<ref>{{harvnb|Najjar|1999|p=93}}.</ref> | |||

=== | ====Influences and antecedents==== | ||

According to Bushrui and Jenkins, an "inexhaustible" source of influence on Gibran was the [[Bible]], especially the [[King James Version]].<ref>{{harvnb|Bushrui|Jenkins|1998|p=}}{{page needed|date=December 2020}}</ref> Gibran's literary oeuvre is also steeped in the Syriac tradition.<ref>{{harvnb|Larangé|2009|p=65}}</ref> According to Haskell, Gibran once told her that {{blockquote|The [King James] Bible is [[Syriac literature]] in English words. It is the child of a sort of marriage. There's nothing in any other tongue to correspond to the English Bible. And the Chaldo-Syriac is the most beautiful language that man has made—though it is no longer used.{{sfn|Gibran|Gibran|1991|p=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranhisl00gibr/page/313/mode/1up 313]}}{{efn|Gibran reportedly once asked Syriac Orthodox Patriarch [[Ignatius Aphrem I]], who was still Archbishop of the Americas, to translate the poems of [[Ephrem the Syrian]] as people only deserved to read them.{{sfn |Kiraz |2019 |p=137}}}}}} As worded by Waterfield, "the parables of the New Testament" affected "his parables and homilies" while "the poetry of some of the Old Testament books" affected "his devotional language and incantational rhythms."<ref>{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|loc=chapter 10, note 46}}.</ref> Annie Salem Otto notes that Gibran avowedly imitated the style of the Bible, whereas other Arabic authors from his time like Rihani unconsciously imitated the [[Quran]].<ref>{{harvnb|Otto|1963|p=44}}</ref> | |||

[[File:William Blake by Thomas Phillips - cropped and downsized.jpg|thumb|upright|Portrait of [[William Blake]] by [[Thomas Phillips]] (detail)]] | |||

According to Ghougassian, the works of English poet [[William Blake]] "played a special role in Gibran's life", and in particular "Gibran agreed with Blake's ''apocalyptic vision'' of the world as the latter expressed it in his poetry and art."<ref name="Ghougassian 1973, p. 56">{{harvnb|Ghougassian|1973|p=56}}.</ref> Gibran wrote of Blake as "the God-man," and of his drawings as "so far the profoundest things done in English—and his vision, putting aside his drawings and poems, is the most godly."<ref>{{harvnb|Ghougassian|1973|p=57}}.</ref> According to George Nicolas El-Hage, | |||

{{blockquote|There is evidence that Gibran knew some of Blake's poetry and was familiar with his drawings during his early years in Boston. However, this knowledge of Blake was neither deep nor complete. Kahlil Gibran was reintroduced to William Blake's poetry and art in Paris, most likely in [[Auguste Rodin]]'s studio and by Rodin himself [on one of their two encounters in Paris after Gibran had begun his Temple of Art portrait series{{efn|name=Temple of Art}}].<ref>{{harvnb|El-Hage|2002|p=14}}.</ref>}} | |||

[[File:Francis Marash (sic) by Kahlil Gibran.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Drawing of [[Francis Marrash]] by Gibran, {{circa|1910}}]] | |||

Gibran was also a great admirer of Syrian poet and writer [[Francis Marrash]],<ref>{{harvnb|Moreh|1976|p=[{{Google books |id=G7Q3AAAAIAAJ |page=45 |plainurl=yes}} 45]}}; {{harvnb |Jayyusi |Tingley |1977 |p=23}}.</ref> whose works Gibran had studied at the Collège de la Sagesse.<ref name="Bushrui 55">{{harvnb|Bushrui|Jenkins|1998|p=[https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranmanp00suhe/page/55/mode/1up 55]}}.</ref> According to [[Shmuel Moreh]], Gibran's own works echo Marrash's style, including the structure of some of his works and "many of [his] ideas on enslavement, education, women's liberation, truth, the natural goodness of man, and the corrupted morals of society."{{sfn|Moreh|1988|p=[{{Google books |id=Z3ev5F1632kC |page=95 |plainurl=yes}} 95]}} Bushrui and Jenkins have mentioned Marrash's concept of universal love, in particular, in having left a "profound impression" on Gibran.<ref name="Bushrui 55"/> | |||

Another influence on Gibran was American poet [[Walt Whitman]], whom Gibran followed "by pointing up the universality of all men and by delighting in nature.{{sfn|Hishmeh|2009|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=Vvl5DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA102 102]}}{{efn|Richard E. Hishmeh has drawn comparisons between passages from ''The Prophet'' and Whitman's "[[Song of Myself]]" and ''[[Leaves of Grass]]''.{{sfn|Hishmeh|2009|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=Vvl5DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA102 102–103]}}}} According to El-Hage, the influence of German philosopher [[Friedrich Nietzsche]] "did not appear in Gibran's writings until ''The Tempests''."<ref name="El-Hage">{{harvnb|El-Hage|2002|p=154}}.</ref> Nevertheless, although Nietzsche's style "no doubt fascinated" him, Gibran was "not the least under his spell":<ref name="El-Hage"/> | |||

{{blockquote|The teachings of [[Almustafa]] are decisively different from [[Thus Spoke Zarathustra|Zarathustra]]'s philosophy and they betray a striking imitation of Jesus, the way Gibran pictured Him.<ref name="El-Hage"/>}} | |||

====Critics==== | |||

Gibran was neglected by scholars and critics for a long time.<ref name="Bushrui & Munro">{{harvnb|Bushrui|Munro|1970|loc=Introduction}}.</ref> Bushrui and John M. Munro have argued that "the failure of serious Western critics to respond to Gibran" resulted from the fact that "his works, though for the most part originally written in English, cannot be comfortably accommodated within the Western literary tradition."<ref name="Bushrui & Munro"/> According to El-Hage, critics have also "generally failed to understand the poet's conception of imagination and his fluctuating tendencies towards nature."<ref>{{harvnb|El-Hage|2002|p=92}}.</ref> | |||

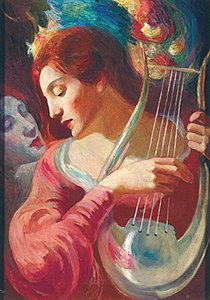

===Visual art=== | |||

{{See also|List of works by Kahlil Gibran#Visual art}} | |||

====Overview==== | |||

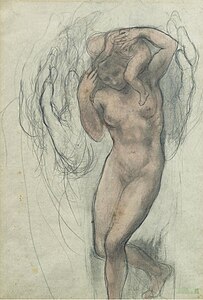

According to Waterfield, "Gibran was confirmed in his aspiration to be a [[Symbolist painter]]" after working in Marcel-Béronneau's studio in Paris.<ref name="Waterfield chapter 5"/> [[Oil paint]] was Gibran's "preferred medium between 1908 and 1914, but before and after this time he worked primarily with pencil, ink, [[watercolor]] and [[gouache]]."{{sfn |McCullough |2005 |p=184}} In a letter to Haskell, Gibran wrote that "among all the English artists [[J. M. W. Turner|Turner]] is the very greatest."<ref>{{harvnb|Otto|1970|p=47}}.</ref> In her diary entry of March 17, 1911, Haskell recorded that Gibran told her he was inspired by J. M. W. Turner's painting ''[[The Slave Ship]]'' (1840) to utilize "raw colors [...] one over another on the canvas [...] instead of killing them first on the palette" in what would become the painting ''Rose Sleeves'' (1911, [[Telfair Museums]]).{{sfn |McCullough |2005 |p=184}}{{sfn|Otto|1965|p=16}} | |||

Gibran created more than seven hundred visual artworks, including the Temple of Art portrait series.{{sfn |Amirani |Hegarty |2012}} His works may be seen at the [[Gibran Museum]] in Bsharri; the [[Telfair Museums]] in Savannah, Georgia; the [[Museo Soumaya]] in Mexico City; [[Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art]] in Doha; the [[Brooklyn Museum]] and the [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]] in New York City; and the [[Harvard Art Museums]]. A possible Gibran painting was the subject of a September 2008 episode of the PBS TV series ''[[History Detectives]]''. | |||

[ | |||

=== | ====Gallery==== | ||

<gallery mode="packed-hover" heights="200px"> | |||

Ages of Women by Kahlil Gibran - Soumaya.jpg|''The Ages of Women'', 1910 ([[Museo Soumaya]]) | |||

Khalil Gibran - Autorretrato con musa, c. 1911.jpg|''Self-Portrait and Muse'', {{circa}} 1911 ([[Museo Soumaya]]) | |||

Untitled (Rose Sleeves) by Kahlil Gibran.jpg|''Untitled (Rose Sleeves)'', 1911 ([[Telfair Museums]]) | |||

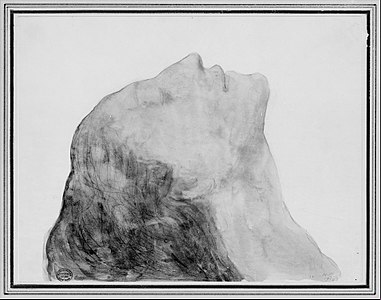

Towards the Infinite (Kamila Gibran, mother of the artist) MET 87681.jpg|''Towards the Infinite (Kamila Gibran, mother of the artist)'', 1916 ([[Metropolitan Museum of Arts]]) | |||

The Three are One by Kahlil Gibran.jpg|''The Three are One'', 1918 ([[Telfair Museums]]), also ''[[The Madman (book)|The Madman]]''{{'}}s frontispiece | |||

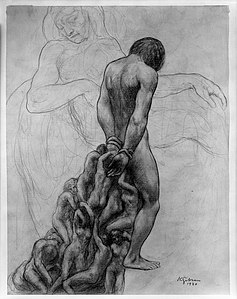

The Slave by Kahlil Gibran.jpg|''The Slave'', 1920 ([[Harvard Art Museums]]) | |||

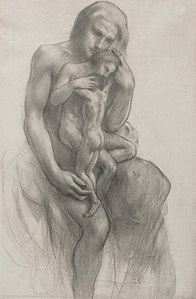

Standing Figure and Child by Kahlil Gibran.jpg|''Standing Figure and Child'', undated ([[Barjeel Art Foundation]]) | |||

</gallery> | |||

==Religious views== | |||

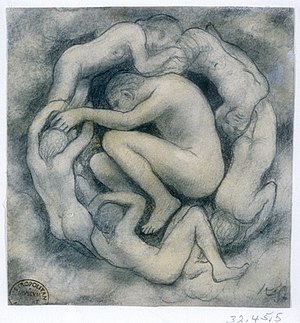

[[File:Sketch for "Jesus the Son of Man" MET 32.45.5 - color.jpg|thumb|A 1923 sketch by Gibran for his book ''Jesus the Son of Man'' (published 1928){{sfn |Metropolitan Museum of Art}}]] | |||

According to Bushrui and Jenkins, | |||

{{blockquote|Although brought up as a [[Maronite]] Christian {{see above|{{section link||Childhood}}}}, Gibran, as an Arab, was influenced not only by his own religion but also by Islam, especially by the mysticism of the [[Sufi]]s. His knowledge of Lebanon's bloody history, with its destructive factional struggles, strengthened his belief in the fundamental unity of religions.<ref name="Bushrui 55"/>}} | |||

Besides Christianity, Islam and Sufism, Gibran's mysticism was also influenced by [[theosophy]] and [[Carl Jung|Jung]]ian psychology.<ref>{{harvnb|Chandler|2017|p=106}}</ref> | |||

Around 1911–1912, Gibran met with [[ʻAbdu'l-Bahá]], the leader of the [[Baháʼí Faith]] who was visiting the United States, to draw his portrait. The meeting made a strong impression on Gibran.{{sfn |Cole |2000}}<ref name="gail"/> One of Gibran's acquaintances later in life, [[Juliet Thompson]], herself a Baháʼí, reported that Gibran was unable to sleep the night before meeting him.<ref name="Bushrui 55"/><ref>{{harvnb|Young|1945}}.</ref> This encounter with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá later inspired Gibran to write ''Jesus the Son of Man''<ref>{{harvnb|Kautz|2012|p=248}}.</ref> that portrays Jesus through the "words of seventy-seven contemporaries who knew him – enemies and friends: Syrians, Romans, Jews, priests, and poets."{{sfn |Gibran |1928 |loc=[https://archive.org/details/jesussonofman00gibr/page/n267/mode/2up back cover]}} After the death of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Gibran gave a talk on religion with Baháʼís{{sfn|''The Brooklyn Daily Eagle''|1921}} and at another event with a viewing of a movie of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Gibran rose to proclaim in tears an exalted station of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and left the event weeping.<ref name="gail">{{harvnb|Thompson|1978}}.</ref>{{sfn|''The Brooklyn Daily Eagle''|1928}} | |||

In | In the poem "The Voice of the Poet" ({{lang|ar|صوت الشاعر}}), published in ''A Tear and a Smile'' (1914),{{efn|Daniela Rodica Firanescu deems probable that the poem was first published in an American Arabic-language magazine.<ref>{{harvnb|Firanescu|2011|p=72}}.</ref>}} Gibran wrote: | ||

{{verse translation|lang=ar|rtl1=y|italicsoff=y|انت اخي وانا احبك ۔<br/>احبك ساجداً في جامعك وراكعاً في هيكلك ومصلياً في كنيستك ، فأنت وانا ابنا دين واحد هو الروح ، وزعماء فروع هذا الدين اصابع ملتصقة في يد الالوهية المشيرة الى كمال النفس ۔{{sfn |Gibran |1950|p=166}}|You are my brother and I love you.<br/>I love you when you prostrate yourself in your mosque, and kneel in your church and pray in your synagogue.<br/>You and I are sons of one faith—the Spirit. And those that are set up as heads over its many branches are as fingers on the hand of a divinity that points to the Spirit's perfection.|attr2=Translated by H. M. Nahmad<ref>{{harvnb|Gibran|2007|p=878}}.</ref>}} | |||

In 1921, Gibran participated in an "interrogatory" meeting on the question "Do We Need a New World Religion to Unite the Old Religions?" at [[St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery]].{{sfn|''The Brooklyn Daily Eagle''|1921}} | |||

==Political thought== | |||

According to Young, | |||

{{blockquote|During the last years of Gibran's life there was much pressure put upon him from time to time to return to Lebanon. His countrymen there felt that he would be a great leader for his people if he could be persuaded to accept such a role. He was deeply moved by their desire to have him in their midst, but he knew that to go to Lebanon would be a grave mistake.<br/>"I believe I could be a help to my people," he said. "I could even lead them—but they would not be led. In their anxiety and confusion of mind they look about for some solution to their difficulties. If I went to Lebanon and took the little black book [''The Prophet''], and said, 'Come let us live in this light,' their enthusiasm for me would immediately evaporate. I am not a politician, and I would not be a politician. No. I cannot fulfill their desire."<ref>{{harvnb|Young|1945|p=125}}.</ref>}} | |||

= | Nevertheless, Gibran called for the adoption of Arabic as a national language of Syria, considered from a geographic point of view, not as a political entity.<ref>{{harvnb|Najjar|2008|p=27 (note 2)}}.</ref> When Gibran met [[ʻAbdu'l-Bahá]] in 1911–12, who [[`Abdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West|traveled]] to the United States partly to promote peace, Gibran admired the teachings on peace but argued that "young nations like his own" be freed from Ottoman control.{{sfn |Cole |2000}} Gibran also wrote the famous "Pity the Nation" poem during these years, posthumously published in ''[[The Garden of the Prophet]]''.{{sfn |''artsyhands.com'' |2009}} | ||

On May 26, 1916, Gibran wrote a letter to [[Mary Haskell (educator)|Mary Haskell]] that reads: "The [[Great Famine of Mount Lebanon|famine in Mount Lebanon]] has been planned and instigated by the Turkish government. Already 80,000 have succumbed to starvation and thousands are dying every single day. The same process happened [[Armenian genocide|with the Christian Armenians]] and applied to the Christians in Mount Lebanon."{{sfn |Ghazal |2015}} Gibran dedicated a poem named "Dead Are My People" to the fallen of the famine.{{sfn |Gibran |1916}} | |||

When the Ottomans were eventually driven from Syria during [[World War I]], Gibran sketched a euphoric drawing "Free Syria", which was then printed on the special edition cover of the Arabic-language paper ''[[As-Sayeh]]'' (''The Traveler''; founded 1912 in New York by Haddad{{sfn|Bawardi|2014|p=[{{Google books |id=D4yhAwAAQBAJ |page=PT101 |plainurl=yes}} 69]}}).<ref name="Beshara">{{harvnb|Beshara|2012|p=[{{Google books|nr9Ivt-pc0IC|page=149|plainurl=yes}} 149]}}</ref> Adel Beshara reports that, "in a draft of a play, still kept among his papers, Gibran expressed great hope for national independence and progress. This play, according to [[Khalil Hawi]], 'defines Gibran's belief in [[Syrian nationalism]] with great clarity, distinguishing it from both [[Lebanese nationalism|Lebanese]] and [[Arab nationalism]], and showing us that nationalism lived in his mind, even at this late stage, side by side with internationalism.{{' "}}<ref name="Beshara"/> | |||

According to Waterfield, Gibran "was not entirely in favour of [[socialism]] (which he believed tends to seek the lowest common denominator, rather than bringing out the best in people)".<ref>{{harvnb|Waterfield|1998|p=188}}.</ref> | |||

==Legacy== | |||

| | The popularity of ''[[The Prophet (book)|The Prophet]]'' grew markedly during the 1960s with the [[Counterculture of the 1960s|American counterculture]] and then with the flowering of the [[New Age]] movements. It has remained popular with these and with the wider population to this day. Since it was first published in 1923, ''The Prophet'' has never been out of print. It has been [[Translations of The Prophet|translated into more than 100 languages]], making it among the top ten most translated books in history.{{sfn |Kalem |2018}} It was one of the best-selling books of the twentieth century in the United States. <ref>{{Cite web |title="The Prophet," by Lebanese-American poet-philosopher Kahlil Gibran, is published |url=https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-prophet-kahlil-gibran-published |access-date=2023-08-02 |website=HISTORY |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| url = https://www. | |||

| | |||

| language = | |||

}}</ref> | |||

== | {{Multiple image|image1=Elvis Presley's first copy of The Prophet.jpg|image2=11.Elvis Presley's Prophet.jpg|footer=Handwritten notes in [[Elvis Presley]]'s copy of ''The Prophet''}} | ||

[[Elvis Presley]] referred to Gibran's ''The Prophet'' for the rest of his life after receiving his first copy as a gift from his girlfriend [[June Juanico]] in July 1956.<ref>{{harvnb|Tillery|2013|loc=Chapter 5: Patriot}}; {{harvnb|Keogh|2004|pp=[https://archive.org/details/elvispresleymanl00keog_0/page/84/mode/2up?q=Gibran 85], [https://archive.org/details/elvispresleymanl00keog_0/page/92/mode/2up?q=Gibran 93]}}.</ref> His marked-up copy still exists in Lebanon<ref>[https://www.kahlilgibran.com/archives/written-works/601-elvis-presley-s-first-copy-of-the-prophet-1955/file.html Gibran National Museum]</ref> and another at the Elvis Presley museum in [[Düsseldorf]].{{sfn |Tillery |2013 |loc=Chapter 5: Patriot}} A line of poetry from ''Sand and Foam'' (1926), which reads "Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so that the other half may reach you," was used by [[John Lennon]] and placed, though in a slightly altered form, into the song "[[Julia (Beatles song)|Julia]]" from [[the Beatles]]' 1968 album ''[[The Beatles (album)|The Beatles]]'' (a.k.a. "The White Album").{{sfn |''BBC World Service'' |2012}} | |||

== | [[Johnny Cash]] recorded ''The Eye of the Prophet'' as an audio cassette book, and Cash can be heard talking about Gibran's work on a track called "Book Review" on his 2003 album ''[[Unearthed (Johnny Cash album)|Unearthed]]''. British singer [[David Bowie]] mentioned Gibran in the song "[[The Width of a Circle]]" from Bowie's 1970 album ''[[The Man Who Sold the World (album)|The Man Who Sold the World]]''. Bowie used Gibran as a "hip reference,"{{sfn |col1234 |2010}}{{better source needed|reason=This source is a blog and may violate the [[WP:SELFPUBLISH]] policy.|date=November 2020}} because Gibran's work ''A Tear and a Smile'' became popular in the [[hippie]] counterculture of the 1960s. In 1978 Uruguayan musician Armando Tirelli recorded an album based on ''The Prophet''.{{sfn |''Light In The Attic Records''}} In 2016 Gibran's fable "On Death" from ''The Prophet'' was composed in Hebrew by [[Gilad Hochman]] to the unique setting of soprano, [[theorbo]] and percussion, and it premiered in France under the title ''River of Silence''.{{sfn|''River of Silence''|2016}} | ||

In 2018, [[Nadim Naaman]] and [[Dana Al Fardan]] devoted their musical ''Broken Wings'' to Kahlil Gibran's novel of [[Broken Wings (Gibran novel)|the same name]]. The world premiere was staged in London's [[Theatre Royal Haymarket]].{{sfn |''Broken Wings - The Musical'' |2015}} | |||

=== | ===Memorials and honors=== | ||

{{Multiple image|width=150|image1=Gebrag_Khalil_Garden_(4694182661)_cropped.jpg|image2=KhalilGibranMemorial01.jpg|footer=[[Gibran Khalil Gibran Garden]] in [[Beirut]] (left), and [[Kahlil Gibran Memorial Garden]] in [[Washington, D.C.]] (right)}} | |||

A number of places, monuments and educational institutions throughout the world are named in honor of Gibran, including the [[Gibran Museum]] in Bsharri, the Gibran Memorial Plaque in [[Copley Square]], Boston,<ref name="Donovan 2011, p. 11">{{harvnb|Donovan|2011|p=11}}.</ref> the [[Gibran Khalil Gibran Garden]] in Beirut,<ref>{{harvnb|Chandler|2017|p=[{{Google books|unQqDwAAQBAJ|page=28|plainurl=yes}} 28]}}.</ref> the [[Kahlil Gibran Memorial Garden]] in Washington, D.C.,<ref name="Donovan 2011, p. 11"/> the [[Khalil Gibran International Academy]] in Brooklyn,{{sfn |Ghattas |2007}} and the Khalil Gibran Elementary School in [[Yonkers, NY]].{{sfn |''Kahlil Gibran School: About Our School''}} | |||

A [[Gibran (crater)|crater]] on Mercury was named in his honor in 2009.<ref name=gpn>{{gpn|14581}}</ref> | |||

{{ | |||

== | ==Family== | ||

American sculptor [[Kahlil Gibran (sculptor)|Kahlil G. Gibran]] (1922–2008) was a cousin of Gibran.<ref name="Gibran, Gibran & Hayek 2017"/> The Katter political family in Australia was also related to Gibran. He was described in parliament as a cousin of [[Bob Katter Sr.]], a long-time member of the Australian parliament and one-time Minister for the Army, and through him his son [[Bob Katter Jr.|Bob Katter]], founder of [[Katter's Australian Party]] and former Queensland state minister, and state politician [[Robbie Katter]].{{sfn|Jones|1990}} | |||

== | ==Notes== | ||

{{Reflist|group=lower-alpha}} | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

=== Citations === | |||

{{Reflist|colwidth=25em}} | |||

== | |||

== | == Cited works == | ||

{{ | {{refbegin|colwidth=25em}} | ||

* {{cite | *{{cite magazine |last=Acocella |first=Joan |author-link=Joan Acocella |date=December 30, 2007 |publication-date=January 7, 2008 |title=Prophet Motive: The Kahlil Gibran phenomenon |magazine=[[The New Yorker]] |url=https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/01/07/prophet-motive }} | ||

* {{cite | *{{cite encyclopedia |surname=Allen |given=R.M.A. |authorlink=Roger Allen (translator) |editor-surname=Greene |editor-given=Roland |editor-link=Roland Greene |display-editors=etal |entry=Arabic poetry |title=The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics |edition=4th rev. |year=2012 |pages=65–72 |entry-url={{Google books|id=uKiC6IeFR2UC|plainurl=y|page=65|keywords=|text=}} |url={{Google books|id=uKiC6IeFR2UC|plainurl=y}} |place=Princeton, NJ |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-15491-6 }} | ||

*{{cite news |last1=Amirani |first1=Shoku |last2=Hegarty |first2=Stephanie |title=Kahlil Gibran's The Prophet: Why is it so loved? |publisher=BBC News |agency=BBC World Service |date=May 12, 2012 |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-17997163 |access-date=November 25, 2020 }} | |||

* {{cite | *{{citation |author=Arab Information Center |title=The Arab world |journal=The Arab World |location=New York |publisher=Arab Information Center |year=1955 |oclc=1481760 |volume=1}} | ||

* {{ | *{{cite web |title=Armando Tirelli - El Profeta |website=Light In The Attic Records |url=https://lightintheattic.net/releases/1331-el-profeta |ref={{sfnref |Light In The Attic Records}} |access-date=April 8, 2021 }} | ||

* {{cite | *{{cite book |editor-last=Bashshur |editor-first=Rashid L |editor-last2=McCarus |editor-first2=Ernest Nasseph |editor-last3=Yacoub |editor-first3=A.I. |title=Contemporary Arabic readers |location=Ann Arbor |publisher=Univ. of Michigan Press |language=ar, en |year=1963 |oclc=62023693}} | ||

* {{cite book|last= | *{{cite book |last=Bawardi |first=Hani J. |title=The Making of Arab Americans: from Syrian Nationalism to U.S. citizenship |publisher=University of Texas Press |location=Austin, TX |year=2014 |doi=10.7560/757486 |isbn=9781477307526 |oclc=864366332 |jstor=10.7560/757486}} | ||

* {{cite book|last= | *{{cite AV media |website=bbc.co.uk |date=May 6, 2012 |title=Heart and Soul, The Man Behind The Prophet |medium=Radio broadcast |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00r49dp |location=London |publisher=BBC World Service |ref={{sfnref |''BBC World Service'' |2012}} }}{{time needed|date=November 2020}} | ||

* {{cite | *{{cite book |last=Beshara |first=Adel |chapter=A Rebel Syrian, Gibran Kahlil Gibran |title=The Origins of Syrian Nationhood: Histories, Pioneers and Identity |publisher=Routledge |location=Abingdon, Oxon ; New York |year=2012 |isbn=9781136724503 |oclc=1058079750 |chapter-url={{Google books|nr9Ivt-pc0IC|page=143|plainurl=yes}} |pages=143–160 }} | ||

*{{cite web |title=Broken Wings - The Musical |website=brokenwingsmusical.com |url=https://brokenwingsmusical.com/ |date=May 12, 2015 |ref={{sfnref |Broken Wings - The Musical |2015}} |access-date=November 29, 2020 }} | |||

* {{cite | *{{cite conference |editor1-last=Bushrui |editor1-first=Suheil B. |editor-link1=Suheil Bushrui |editor2-last=Munro |editor2-first=Jon M. |title=Kahlil Gibran: Essays and Introductions |year=1970 |conference=Gibran International Festival, May 23–30, 1970 |publisher=Rihani House |location=Beirut |oclc=1136103676}} | ||

* {{ | *{{Cite book|last=Bushrui|first=Suheil B.|author-link=Suheil Bushrui|title=Kahlil Gibran of Lebanon: A Re-Evaluation of the Life and Work of the Author of The Prophet|year=1987|publisher=C. Smythe |location=Gerrards Cross, UK |oclc=16470732|isbn=9780861402793}} | ||

* {{ | *{{Cite book|last1=Bushrui|first1=Suheil B.|author-link=Suheil Bushrui|last2=Jenkins|first2=Joe|author-link2=Joe Jenkins (scholar)|title=Kahlil Gibran, Man and Poet: a New Biography|year=1998|publisher=Oneworld Publications|isbn=9781851682676|oclc=893209487|url=https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranmanp00suhe|url-access=registration}} | ||

* {{ | *{{cite book |last=Cachia |first=Pierre |title=Arabic literature : an overview |publisher=RoutledgeCurzon |location=London |year=2002 |isbn=9780700717255 |oclc=252908467 |url=https://archive.org/details/arabicliterature0000cach }} | ||

*{{cite book |last=Chandler |first=Paul-Gordon |author-link=Paul-Gordon Chandler |title=In Search of a Prophet: A Spiritual Journey with Kahlil Gibran |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |location=Lanham, MD, US |year=2017 |isbn=9781538104286 |oclc=992437957 |url={{Google books|unQqDwAAQBAJ|page=pp1|plainurl=yes}} }} | |||

* {{cite | *{{cite web |last=Cole |first=Juan R. I. |author-link=Juan Cole |title=Chronology of his Life |year=2000 <!--year of earliest archive--> |work=Juan Cole's Khalil Gibran Page – Writings, Paintings, Hotlinks, New Translations |publisher=Professor Juan R.I. Cole |url=http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jrcole/gibran/chrono.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000119023044/http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jrcole/gibran/chrono.htm |archive-date=January 19, 2000 |url-status=dead }} | ||

* {{ | *{{cite web |author=col1234 |title=The Width of a Circle |website=Pushing Ahead of the Dame: The Width of a Circle |date=January 3, 2010 |url=https://bowiesongs.wordpress.com/tag/khalil-gibran/ |access-date=November 29, 2020 }} | ||

* {{cite | *{{cite book |last=Corm |first=Charles |author-link=Charles Corm |translator-last=Goff-Kfouri |translator-first=Carol-Ann |editor-last=Jahshan |editor-first=Paul |title=The sacred mountain |publisher=Notre Dame University Press |publication-place=Louaize, Lebanon |year=2004 |orig-year=1934 |isbn=9789953418889 |oclc=54999908}} | ||

* {{cite | *{{Cite book|last=Dahdah|first=Jean-Pierre|title=Khalil Gibran, une biographie|year=1994|publisher=Albin Michel|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nVqQuWegrskC|language=fr|isbn=9782226075512}} | ||

*{{cite book |last=Daoudi |first=M. S. |title=The meaning of Kahlil Gibran |publisher=Citadel Press |location=Secaucus, NJ |year=1982 |isbn=9780806508047 |oclc=1150277275 |url=https://archive.org/details/meaningofkahlilg0000daou }} | |||

* {{ | *{{cite web |title=Definition of Gibran |website=dictionary.com |date=September 20, 2012 |url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/gibran |ref={{sfnref |dictionary.com |2012}} |access-date=November 25, 2020 }} | ||

* {{cite book|last= | *{{cite news |title=Do We Need a New World Religion to Unite the Old Religions? |newspaper=The Brooklyn Daily Eagle |location=Brooklyn, NY |page=7 |date=March 26, 1921 |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/4729852/talk_by_kahlil_gibran_with_bahais/ |access-date=November 27, 2020 |via=Newspapers.com |ref={{sfnref|''The Brooklyn Daily Eagle''|1921}} }} | ||

* {{cite | *{{cite book |last=Donovan |first=Sandra |title=The Middle Eastern American experience |publisher=Twenty-First Century Books |location=Minneapolis |year=2011 |isbn=9780761363613 |oclc=667202530}} | ||

* {{cite | *{{cite book |last=El-Hage |first=George Nicolas |title=William Blake & Kahlil Gibran : poets of prophetic vision |publisher=NDU Press |location=Louaize, Lebanon |year=2002 |isbn=9789953418407 |oclc=249027104}} | ||

* {{cite book|last= | *{{Cite journal | last =Firanescu | first =Daniela Rodica | title =Renewing thought from exile: Gibran on the New Era | journal =Synergies Monde Arabe | volume =8 | issue =2011 | pages =67–80 | date =2011 | url =https://gerflint.fr/Base/Mondearabe8/rodica_firanescu.pdf | issn =1766-2796 | oclc =823342904 | access-date =October 23, 2019 }} | ||

{{ | *{{cite web |last=Ghattas |first=Kim |title=New York Arabic school sparks row |website=BBC News |date=September 6, 2007 |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/6980966.stm }} | ||

*{{cite web |last=Ghazal |first=Rym |title=Lebanon's dark days of hunger: The Great Famine of 1915-18 |date=April 14, 2015 |website=The National |url=https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/lebanon-s-dark-days-of-hunger-the-great-famine-of-1915-18-1.70379 |access-date=November 28, 2020 }} | |||

*{{cite book |contributor-last=Ghougassian |contributor-first=Joseph P |contribution=The Contributions of the Writer |volume=Book Three |last1=Sherfan |first1=Andrew Dib |last2=Gibran |first2=Kahlil |editor-last=Sherfan |editor-first=Andrew Dib |title=A Third Treasury of Kahlil Gibran |location=Secaucus, NJ |publisher=Citadel Press |year=1974 |isbn=9780806504032 |id={{OCLC|654736185|793493890}} |url=https://archive.org/details/thirdtreasuryofk0000sher }} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Ghougassian |first=Joseph |author-link=Joseph Ghougassian |title=Kahlil Gibran: Wings of Thought; the people's philosopher |publisher=Philosophical Library |location=New York |year=1973 |isbn=9780802221155 |oclc=569449532 |url=https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranwing00ghou |url-access=registration }} | |||

*{{cite web |title=Gibran: Birth and Childhood |website=leb.net |url=http://leb.net/gibran/bio/1.html |ref={{sfnref |Gibran: Birth and Childhood}} |access-date=November 27, 2020 }} | |||

*{{cite book |last1=Gibran |first1=Jean |last2=Gibran |first2=Kahlil |title=Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World |location=New York |publisher=Interlink Books |year=1991 |orig-year=1970 |isbn=9780940793798 |oclc=988544667 |url=https://archive.org/details/kahlilgibranhisl00gibr |url-access=registration }} | |||

*{{cite book |last1=Gibran |first1=Jean |last2=Gibran |first2=Kahlil |last3=Hayek |first3=Salma |author-link3=Salma Hayek |title=Kahlil Gibran: Beyond Borders |publisher=Interlink Books |location=Northampton, MA, US |year=2017 |isbn=9781566560931 |oclc=936349669}} | |||

*{{cite web |last=Gibran |first=Khalil |title=Dead Are My People |date=October 1916 |website=PoemHunter.com |url=https://www.poemhunter.com/best-poems/khalil-gibran/dead-are-my-people/ |access-date=November 29, 2020 }} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Gibran |first=Kahlil |title=Jesus the Son of Man |location=New York, NY |publisher=A.A. Knopf |year=1928 |oclc=589037866 |url=https://archive.org/details/jesussonofman00gibr }} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Gibran |first=Kahlil |title=Damʻah wa-ibtisāmah (دمعة وابتسامة) |trans-title=A tear and a smile |language=ar |year=1950 |url=https://dlib.nyu.edu/aco/book/nyu_aco000506 |website=Arabic Collections Online |location=Bayrūt |publisher=Maktabat Ṣādir |via=New York University Libraries |access-date=November 27, 2020 |oclc=1029000174 }} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Gibran |first=Kahlil |title=Kahlil Gibran : a self-portrait |editor-last=Ferris |editor-first=Anthony R |translator-last=Ferris |translator-first=Anthony R |publisher=Citadel Press |location=New York |year=1959 |isbn=9780806501086 |id={{OCLC|838375| 1150021694}} |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9782866005276 }} | |||

*{{Cite book|last=Gibran|first=Kahlil|year=2007|publisher=Alfred A. Knopf|title=The Collected Works|isbn=9780307267078|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uy7uAAAAMAAJ}} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Haiek |first=Joseph |title=Arab-American Almanac |publisher=News Circle Pub. House |location=Glendale, CA, US |year=2003 |isbn=9780915652211 |oclc=57206425 |edition=5th}} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Hajjar |first=Nijmeh |title=The Politics and Poetics of Ameen Rihani : the Humanist Ideology of an Arab-American Intellectual and Activist |publisher=I.B. Tauris & Co |location=London |year=2010 |isbn=9780857718167 |oclc=682882079}} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Hishmeh |first=Richard E. |chapter=Strategic Genius, Disidentification, and the Burden of ''The Prophet'' in Arab-America Poetry |title=Arab Voices in Diaspora: Critical Perspectives on Anglophone Arab Literature |publisher=Rodopi |location=Amsterdam New York, NY |year=2009 |isbn=9789042027190 |oclc=559994020 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Vvl5DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA93 |pages=93–120 }} | |||

*{{cite AV media |people=Hochman, Gilad, composer, and the Sferraina Ensemble |date=April 10, 2016 |title=River of Silence |medium=Video |language=he |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YUYzh2aFM8E | archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211103/YUYzh2aFM8E| archive-date=November 3, 2021 | url-status=live|access-date=November 30, 2020 |via=YouTube |ref={{sfnref|''River of Silence''|2016}}}}{{cbignore}} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Jason |first=Philip |title=Critical survey of poetry |volume=v. 3 |edition= 2nd rev. |publisher=Salem Press |location=Pasadena, CA, US |year=2003 |isbn=9781587650741 |oclc=49959198}} | |||

*{{cite book |last1=Jayyusi |first1=Salma Khadra |author-link=Salma Jayyusi |last2=Tingley |first2=Christopher |author-link2=Christopher Tingley |title=Trends and Movements in Modern Arabic Poetry |volume=1 |location=Leiden |publisher=E. J. Brill |year=1977 |isbn=9789004049208 |oclc=879101909}} | |||

* {{cite book |surname=Jayyusi |given=Salma Khadra |authorlink=Salma Jayyusi |year=1977 |title=Trends and Movements in Modern Arabic Poetry |volume=2 |place=Leiden |publisher=E. J. Brill |url={{Google books|id=8pI3AAAAIAAJ|plainurl=y|page=|keywords=|text=}} |isbn=90-04-04920-7 }} | |||

*{{cite book |editor-last=Jayyusi |editor-first=Salma Khadra |title=Modern Arabic Poetry, An Anthology |location=New York |publisher=Columbia University Press |year=1987 |isbn=9780231052733 |oclc=1150851026}} | |||

*{{cite web |last=Jones |first=Barry |author-link=Barry Jones (Australian politician) |title=Death of Hon R.C. Katter |work=Hansard |publisher=Parliament of Australia |date=May 8, 1990 |url=http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=CHAMBER;id=chamber%2Fhansardr%2F1990-05-08%2F0050;orderBy=date-eFirst;page=4;query=(Dataset%3Ahansardr%20SearchCategory_Phrase%3A%22house%20of%20representatives%22)%20Date%3A01%2F01%2F1981%20%3E%3E%2031%2F12%2F2009%20Decade%3A%221990s%22%20Year%3A%221990%22%20Month%3A%2205%22%20Day%3A%2208%22;querytype=Day%3A08;rec=4;resCount=Default |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140513234356/http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=CHAMBER;id=chamber%2Fhansardr%2F1990-05-08%2F0050;orderBy=date-eFirst;page=4;query=(Dataset%3Ahansardr%20SearchCategory_Phrase%3A%22house%20of%20representatives%22)%20Date%3A01%2F01%2F1981%20%3E%3E%2031%2F12%2F2009%20Decade%3A%221990s%22%20Year%3A%221990%22%20Month%3A%2205%22%20Day%3A%2208%22;querytype=Day%3A08;rec=4;resCount=Default |archive-date=May 13, 2014 }} | |||

*{{Cite book |last=Gibran |first=Khalil |contributor-last=Juni |contributor-first=Anne |contribution=Preface |translator-last=Juni |translator-first=Anne |title=Les Dieux de la Terre |trans-title=The Gods of the Earth |contribution-url={{Google books|RRNeMZRy_wAC|page=7|plainurl=yes}} |language=fr |location=Cesson-Sévigné (Ille-et-Vilaine) |publisher=La Part Commune |year=2000 |isbn=9782844180124 |oclc=408306583 }} | |||

*{{cite web |title=Kahlil Gibran School: About Our School |website=Yonkers Public Schools |url=https://www.yonkerspublicschools.org/domain/4826 |ref={{sfnref |Kahlil Gibran School: About Our School}} |access-date=November 13, 2020 |archive-date=August 20, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220820030451/https://www.yonkerspublicschools.org/domain/4826 |url-status=dead }} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Kairouz |first=Wahib |translator-last=Murr |translator-first=Alfred |title=Gibran in His Museum |year=1995 |location=Jounieh, Liban |publisher=Bacharia |oclc=1136110202}} | |||

*{{cite web |last=Kalem |first=Glen |title=The Prophet, translated. |date=April 9, 2018 |website=The Kahlil Gibran Collective |url=https://www.kahlilgibran.com/29-the-prophet-translated-2.html |access-date=November 27, 2020 }} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Karam |first=Antun Ghattas |title=La vie et l'oeuvre litteraire de Gibran Khalil Gibran |trans-title=The life and literary work of Gibran Khalil Gibran |location=Beirut |publisher=Dar An-Nahar |year=1981 |oclc=1012718795 |language=fr}} | |||

*{{cite web |last=Kates |first=Ariel |title=Khalil Gibran: An Immigrant Artist on 10th Street |website=Village Preservation |date=September 3, 2019 |url=https://www.villagepreservation.org/2019/09/03/khalil-gibran-an-immigrant-artist-on-10th-street/ |access-date=November 28, 2020 }} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Kautz |first=William |title=Story Of Jesus : An Intuitive Anthology |publisher=Trafford Publishing |year=2012 |isbn=9781466918092 |oclc=1152313853 |chapter=Appendix A, II. Intuitively Inspired Writers, [KG] Kahlil Gibran |chapter-url={{Google books|vbRXAAAAQBAJ&|page=248|plainurl=yes}} }} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Keogh |first=Pamela Clarke |title=Elvis Presley: The Man. The Life. The Legend |publisher=Atria Books |location=New York |year=2004 |isbn=9781439108154 |oclc=908109375}} | |||

*{{Cite book |last=Kiraz |first=George Anton |author-link=George Kiraz |year=2019 |chapter=4. Bishops Visit… Churches Consecrated (1927–1948) |title=The Syriac Orthodox in North America (1895–1995): A Short History |location=Piscataway, NJ |publisher=Gorgias Press |isbn=9781463240370 |oclc=1090706190 |doi=10.31826/9781463240387|s2cid=202465604 }} | |||

*{{Cite book |last=Larangé |first=Daniel S. |title=Poétique de la fable chez Khalil Gibran (1883–1931). Les avatars d'un genre littéraire et musical : le ''maqām'' |trans-title=Poetics of the fable by Khalil Gibran (1883–1931). The avatars of a literary and musical genre: the ''maqām'' (place) |location=Paris |publisher=L'Harmattan |year=2005 |language=fr |isbn=9782747595001 |oclc=77051946}} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Larangé |first=Daniel S. |chapter=Modernité de la tradition |chapter-url={{Google books|id=OU0S61QQpNEC|page=PA53|plainurl=yes}} |editor-last=Saillant |editor-first=Caroline |title=Paroles, langues et silences en héritage : essais sur la transmission intergénérationnelle aux XXe et XXIe siècles |publisher=Presses universitaires Blaise Pascal |publication-place=Clermont-Ferrand |year=2009 |isbn=9782845164086 |oclc=470968051 |language=fr |pages=53–68 }} | |||

*{{cite book |last=Majāʻiṣ |first=Salīm |title=Antoun Saadeh : a biography |publisher=Kutub |location=Beirut |year=2004 |isbn=9789953417950 |oclc=57005050}} | |||

*{{cite book |last=McCullough |first=Hollis |title=Telfair Museum of Art : collection highlights |publisher=Telfair Museum of Art |location=Savannah, GA, US |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-933075-04-7 |oclc=60935021}} | |||

*{{cite thesis |last=Mcharek |first=Sana |date=Spring 2006 |title=Kahlil Gibran and other Arab American prophets |type=MS |location=Tallahassee, FL |publisher=Florida State University |oclc=70005889 |url=http://etd.lib.fsu.edu/theses/available/etd-04102006-114344/unrestricted/Mcharek2006.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090304041407/http://etd.lib.fsu.edu/theses/available/etd-04102006-114344/unrestricted/Mcharek2006.pdf |archive-date=March 4, 2009 |url-status=dead }} | |||