Varicella zoster virus

Articles that lack this notice, including many Eduzendium ones, welcome your collaboration! |

| Chicken Pox | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| Virus classification | ||||||||||

|

Description and significance

Varicella Zoster Virus usually comes in two forms. Upon the first infection, it produces red, leathery pustules and most often appears in children. This is generally known as "Varicella virus" or chicken pox. If the infection subsequently returns, it is then typically a painful red rash that encompasses most of the body. The small bumps of the rash develop pus, break open and darker crusts replace the blisters. This form of the disease is known as the "Herpes zoster" or shingles part, and mainly afflicts older people, or those with weakened immune systems.

Contrary to popular belief, the Varicella virus does not afflict chickens or any other animals. In fact, the only known hosts for VZV are humans, and people have been reporting cases of Varicella since ancient civilizations.

VZV is thought to be a virus which has coevolved with humans, and over the course of centuries, it has been fairly stable and only one serotype has been found. For Scientists in the 20th century, the importance of sequencing the genome lay not only in uncovering the molecular makeup of the virus, but also in developing a better understanding of how the viral genes function in pathogenicity, as well as its evoloutionary history, so a possible cure could be found. In 1986, Andrew J. Davison and James E. Scott published the entire DNA sequence of Varicella Zoster Virus in the Journal of General Viriology. With the help of M13-dideoxynucleotide technology, they discovered that the genome contained 124884 base pairs, with a total of 70 genes spread out evenly between the two DNA strands. They also compared the amino acid sequences of VZV to that of the Herpes Simplex Virus I, another virus of the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae , and the striking similarities indicate a common ancestral origin. [1]

Since the sequencing of its genome, there have been major developments in trying to prevent Varicella Zoster infection, including a succesful vaccination.

The Virus was first isolated by Dr. Thomas Weller in 1949, from the vesicular lesions of the Chicken Pox and Shingles pustules, and was grown in vitro, in tissue culture. Dr. Weller's research also proved that there was a connection between Varicella and Herpes Zoster virus, namely that Varicella was the causative agent for subsequent reactivation of Herpes Zoster Virus. He was a Nobel Laureate in 1954 for his work in isolating Varicella Zoster Virus, Cytomegalovirus, Mumps. Rubella and Poliomyelitis Viruses in human tissue cultures.

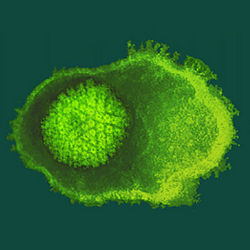

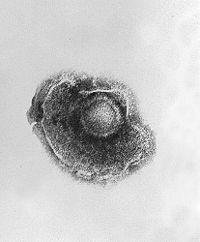

Genome structure

The diameter of Varicella Zoster Virus is about 150-200nM, and has approximately 125,000 base pairs,which incidentally is the smallest of the herpes virus genomes. VZV may encode up to 75 proteins, 70 of which are homologous with Herpes Simplex Virus I. [2] The virion has an icosahedral nucleocapsid made up of 162 capsomeres, and a protein covering separates the nucleocapsid from the lipid envelope that contains the viral glycoproteins. The core consists of a linear, double stranded DNA genome. The Molecular mass of the genome is 80 x 106 daltons, and it contains about 71 open reading frames (ORFs). The infection will bring out the immunoglobulin G, immunoglobulin M, and immunoglobulin A antibodies which will then bind to various viral proteins. [3]

It is an alphaherpes virus, so it has the charecteristic "unique regions" , the unique long and unique short regions, both containing inverted repeat regions. Similar to Herpes Simplex Virus I, it has 3' to 5' exonuclease DNA proofreading by DNA polymerase; this scrupulous proofreading creates minimum additions or deletions of nucleotides, and may be why the virus has been so invariable for hundreds of years. [4]

Ecology

Varicella Zoster interacts solely with humans because there are no animal hosts that have been identified so far. In the body, it interacts with the nasal mucosa area as Varicella, and then with the sensory ganglionic nerves as Zoster.

A study published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in 2001 indicative the effect that the environment may have in being infected by Varicella Zoster disease. In Thailand, 4 distinct climatic differences were studied, and seroprevalence was determined to be higher in cooler areas than warm ones. A delay in natural infection arises in warmer areas with "high extreme minimum temperature". In the warmer areas however, seroprevalence was higher in urban populations than in rural ones. As Lolekha stated,"in the warmer areas, the pattern of adolescent and adult susceptibility was greater in rural than in urban areas...In urban settings, higher population densities may partially overcome the transmission-interrupting effect of a tropical climate"(pp.131,135)[5]

Pathology

The Varicella Zoster Virus causes disease in human hosts by inserting its gene into the host cell at the nasopharyngeal mucosa. It is highly contangious and may be transmitted from humans by contact with chickenpox blister fluid or by airborne infection. The incubation period can be anywhere from 14- 21 days, upon which red, itchy postules develop around the hosts body. Patient symptoms include rash, itching, fever and lethargy. In serious cases, such as for small children and immunocompromised adults, it can lead to severe skin infections, pnuemonia, brain damage or even death. After the varicella infection, it has latency in the sensory ganglionic neurons and may be reactivated years later as the Zoster virus, also known as shingles. Shingles produces painful blisters, and is characterized by a rash on one side of the body. Symptoms include hypersensitive skin, itching, and headache.

Application to Biotechnology

Numerous studies have been done which utilizes the VZV virus as a vector for gene therapy and cancer therapy.

For instance, Varicella-zoster virus thymidine kinase gene(VZVtk) and antiherpetic pyrimidine nucleoside analogues have been used for chemotherapy treatment of cancer. This works by inserting so called "suicide genes" into tumor cells through the viral medium. The VZVtk gene put into human osteosarcoma inhibits proliferation of the tumor cells, thereby helping treat the cancer. [6]

The Varicella Zoster Vaccine

In 1974, Michiaki Takahashi developed a vaccine for VZV when he obtained blood samples from a Japanese boy named Oka who was afflicted with Chicken Pox and attenuated it by growing it in human cell samples. Merck, Sharp & Dohme developed the vaccine in the 1980's as Varivax and it was approved by the FDA in 1995. A Zarivax vaccine was developed by 1997 which is basically concentrated Varivax vaccine, which prevents Shingles in adults. Proquad , the MMRV- Measles, Mumps, Rubella, Varicella Vaccine is another way to get vaccinated, but it contains 10 times more vaccine than Varivax.

The Varicella Zoster Vaccine is nationally recommeded for children starting from as early as 12 months old as a way to prevent getting Varicella Zoster. The vaccine has live, attenuated virus and are based on the Oka strain of varicella.

For Children under 13, one dose of the vaccine is administered, for adults and young adults, two doses, four to eight weeks apart are recommended. The WHO released information in 2003 that 95% of children have seroconversion after recieving the vaccine. Adults and adolescents also have between 75- 99% seroconversion after administration of the two doses.

Side effects of the vaccine can range from fever, mild rash to seizure, brain reactions, low blood counts and pnuemonia, but organizations such as the World Health Organization and Center for Disease Control and Prevention say that these severe problems are very rare, and the benifits of immunity from VZV outweigh the risks of getting the vaccine. The controversy continues over whether getting the vaccine is worth the risk. In addition the immunity from Varivax usually lasts from 10- 20 years, posing a potential threat to people who received the vaccine as children, and may still develop the disease as adults when it will affect them more severely. Additionally, there is something called "Varicella Breakthrough disease" which is the development of the disease even after vaccination, (Usually within 40-45 days). The symptoms are similar to regular Varicella symptoms, red itchy bumps, rash on the body and maculopapular areas may arise, and some argue that natural Varicella Zoster Virus may sometimes be even milder than Varicella Breakthrough disease.

As always, it is a cost- benifit analysis that determines whether or not getting the vaccine is worth the risk.

Current Research

1. Herpes Zoster and Its Cardiovascular Complications in the Elderly – Another Look at a Dormant Virus by Tony S. Ma Tracie C. Collins Gabriel Habib Audrius Bredikis Blase A. Carabello

This study mainly deals with the adverse effects of Herpes Zoster, the latent form of Varicella, on the cardiovascular health of geriatric patients. Numerous patients who had just suffered from Shingles subsequent heart blocks and other cardiovascular problems, and this study hoped to set up corelations between the two. Citing a previous study done by Head and Campbell, which indicates that the site of latency for zoster is in the dorsal root ganglion, they thought that it was the renal colic which stimulates the sensory ganglion to reactivate the Zoster. They continued to say that "The cardiac involvement could either be a result of a secondaryseeding of the pleural and pericardial space occurring through a cell-mediated transport of the VZV or a coincidental reactivation of VZV at the cardiac sympathetic/parasympathetic ganglia."(Tony, p. 4) In the case studies done, the researchers seemed to find that plueral and pericardial effusions were seen in a CT scan very close to when the outbreak of Zoster occured. However, further studies need to be done in order to provide a more conclusive correlation between Zoster and Cardiovascular problems. [7]

2. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=26916461&site=ehost-live Prevention of Varicella

Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)Mona Marin, MD, Dalya Güris, MD,* Sandra S. Chaves, MD, Scott Schmid, PhD, Jane F. Seward, MBBS [8]

3.Gilden DH: Varicella-zoster virus vaccine –grown-ups need it, too. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 2344–2346.

References

Arvin, AM. "Varicella Zoster Virus". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1996. Volume 3. pp.361-381.

6.>[http://www.nature.com/gt/journal/v4/n10/pdf/3300502a.pdf B Degre`ve, G Andrei1, M Izquierdo, J Piette, K Morin, EE Knaus, LI Wiebe, I Basrah, RT Walker, E De Clercq and J Balzarini "Varicella-zoster virus thymidine kinase gene and antiherpetic pyrimidine nucleoside analogues in a combined gene/chemotherapy treatment for cancer". Gene Therapy. 1997. Volume 4.pp.1107–1114]

7 http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/356/11/1121

- ↑ http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Varicella_zoster_virus#_note1

- ↑ Reinhart,W.J.

- ↑ .Arvin, AM. "Varicella Zoster Virus". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1996. Volume 3. p.361-381.

- ↑ Peters, G. Tyler S Grose, C. Severine, A. Gray, M. Upton C. Tipples G.A.. "A Full-Genome Phylogenetic Analysis of Varicella-Zoster Virus Reveals a Novel Origin of Replication-Based Genotyping Scheme and Evidence of Recombination between Major Circulating Clades". Journal of Virology.2006. Volume 80 No. 19 p. 9850-9860.

- ↑ http://www.ajtmh.org/cgi/content/abstract/64/3/131 S Lolekha, W Tanthiphabha, P Sornchai, P Kosuwan, S Sutra, B Warachit, S Chup-Upprakarn, Y Hutagalung, J Weil, and HL Bock "Effect of climatic factors and population density on varicella zoster virus epidemiology within a tropical country" American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.2001. Volume 64 Issue 3, pp.131-136.]

- ↑ [http://www.nature.com/gt/journal/v4/n10/pdf/3300502a.pdf B Degre`ve, G Andrei1, M Izquierdo, J Piette, K Morin, EE Knaus, LI Wiebe, I Basrah, RT Walker, E De Clercq and J Balzarini "Varicella-zoster virus thymidine kinase gene and antiherpetic pyrimidine nucleoside analogues in a combined gene/chemotherapy treatment for cancer". Gene Therapy. 1997. Volume 4.pp.1107–1114

- ↑ Tony S. Ma Tracie C. Collins Gabriel Habib Audrius Bredikis Blase A."Herpes Zoster and Its Cardiovascular Complications in the Elderly – Another Look at a Dormant Virus"Cardiology.2006. Volume 107. p. 63-67.

- ↑ Mona Marin