Human fluid metabolism

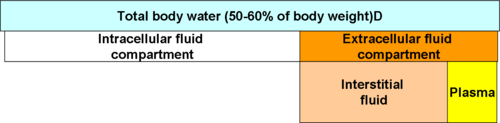

At the most basic, the physiology of human fluid metabolism splits into the extracellular fluid compartment and the intracellular fluid compartment. Even with that separation, there is a constant exchange of water, ions, and non-ionized substances between the compartments and subcompartments. [1]

Electrolytes

In virtually all fluids, not just the concentration, but the ratios of four principal ions are critical:[2]

- Sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+)

- Chloride (Ca+2) and bicarbonate (HCO3+

Several other ions and molecules also are important, but sodium:potassium balance, for example, is fundamental to cell electrical activity.

| Substance | Extracellular volume | Intracellular volume |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium | 135-145 mEq/L | 10-20 mEq/L |

| Potassium | 3.5-5.0 mEq/L | 130-140 mEq/L |

| Chloride | 95-105 mEq/L | |

| Bicarbonate | 22-26 mEq/L | |

| Glucose | 90-120 mg/dL | |

| Calcium | 8.5-10 mg/dL | |

| Magnesium | 1.4-2.1 mg/dL | 20-30 mEqL |

| Urea nitrogen | 10-20 mg/dL | 10-20 mg/dL |

At this point in the diagram, we only distinguish between plasma and interstitial fluid, not urine, lymph, sweat, and other fluids within the extracellular compartment.

Blood versus fluid

Again as a basic idea, blood is plasma that carries blood cells and additional circulating chemicals. Many clinical measurements involving blood chemistry are made on the easier-to-collect blood serum, which is the fluid remaining after blood clots. Serum does not circulate in the body, although it can accumulate near blood clots.

References

- ↑ Arthur C. Guyton and John E. Hall, ed. (2000), Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology, vol. Tenth Edition, W. B. Saunders, ISBN 072168677Xpp. 2-4

- ↑ Richard A. Preston (2002), Acid-Base, Fluids and Electrolytes Made Ridiculously Simple, McMaster, ISBN 0940780313, p. 5