Special Operations Executive

| This article may be deleted soon. | ||

|---|---|---|

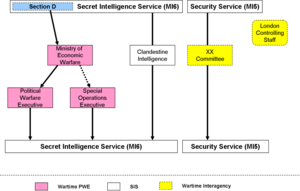

Subordinate to the wartime Ministry of Economic Warfare, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a cadre for guerrilla warfare and direct action in occupied Europe. It was commanded by Colonel Colin Gubbins. Winston Churchill had ordered Hugh Dalton, the Minister of Economic Warfare, to "set Europe ablaze." Background

When Nazi forces entered Austria in 1938, the British government began separate, not necessarily well coordinated strategic planning for secret operations. Inside the Foreign Office, two initiatives began: a psychological warfare analysis group, and a new Section D in the Secret Intelligence Service. In parallel, the War Office set up a guerrilla warfare research group, first called GS(R) and then MI(R). "Initially, informal agreements resulted in section D pursuing ideas in the realm of agents operating in plainclothes, while MI(R) was to explore courses of action that uniformed combatants could pursue. Such a continued division of labor was shortly supplanted by more pragmatic approaches, when in March, 1939 the propaganda service, Section D, and MI(R) were all formally combined, and empowered to begin circumspect operations in addition to just planning them." [1] SOE was chartered in 1940, under the Churchill government. Stewart Menzies had become "C", director of the SIS, in 1939; Churchill had had a different candidate, from the Admiralty, making for interpersonal tension.[2] Organizationally, there was to be conflict among SIS and the Ministry of Economic Warfare. The core of SOE came from Section D of the Secret Intelligence Service. [3]. It has been the conventional wisdom that this is the basic British doctrine, but, as with so many things in the clandestine and covert worlds, it is not that straightforward. [4]. SOE conducted competent training in parachuting, sabotage, irregular warfare, etc. It could check language and marksmanship skills, as well as examining clothing and personal effects for anything that could reveal British manufacture, SOE trained agents in the distinguishing uniforms, insignia, and decorations of the Germans, "But it could not teach them the organization, modus operandi, and psychology of the German intelligence and security services; and it did not call upon the MI-5 and MI-6 experts who did know the subject..."[4] those services also were reluctant to provide SOE with access to their own sensitive sources. While isolating SOE from the clandestine services provided some mutual passive security, it also failed to provide proactive counterintelligence. Operations"The consequences of this shortcoming are evident in the German counterintelligence coups in France, Belgium, and Holland...While the Security Service maintained an extensive name index, the Registry (partially destroyed by German bombing, but otherwise irreplaceable), SOE apparently did not maintain a counterintelligence index against which prospective field recruits could be checked. SOE received help from the British police, but not the security experts. In particular, a large SOE guerrilla network, PROSPER, under Major Francis Suttill, was exposed and destroyed by the Germans, due to poor operational security. There have been speculation that PROSPER, however, may have been sacrificed to cover more secret British operations, such as the penetration of the Nazi Sicherheitsdienst (SD) intelligence service by Alain Dericourt.[5] Disposition"At the end of the war the Foreign Office and the Chiefs of Staff agreed to return the responsibility for covert operations to the jurisdiction of the Secret Intelligence Service. There were three reasons for the change: to ensure that secret intelligence and special operations were the responsibility of a single organization under a single authority; to prevent duplication, wasted effort, crossing of operational wires, friction, and consequent insecurity; and to tailor the size of the covert action staff to the greatly reduced scale of peacetime needs. The peacetime condition also added a new factor which greatly increased the importance of consolidation. [4] References

|

||