Waldo Peirce

Waldo Peirce (December 17, 1884, Bangor, Maine–March 8, 1970, Newburyport, Massachusetts) was, during his lifetime, a prominent American artist.[1] He was also a well-known personality, as famous for his eccentricities as for his painting; this commingling for many years of his artistic career with his public persona may help explain why, upon his death at age 85, he then virtually vanished from the history of American art even though he is well represented in many of the major American museums such as the Metropolitan and the Whitney.[2] Sometimes called "the American Renoir," or "the American Matisse", Peirce never belonged to any well-defined school of art except, perhaps, for a time, the so-called Regionalists; his lack of association with other famous painters may also have diminished his long-term reputation. Born to wealth, Peirce once said that he never worked a day in his life. He did, however, for 50 years, spend many hours every day painting thousands of pictures of his beloved families, still lifes, and landscapes. With a shaggy mustache and full beard and a large cigar jammed perpetually into his mouth, Peirce looked every inch of a cartoonist's notion of an artist. He himself, however, was adamant: "I'm a painter," he insisted, "not an artist."

Style

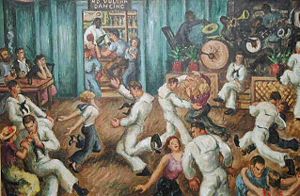

The Silver Slipper dance hall adjacent to Sloppy Joe's in Key West, Florida, frequented by Peirce and Ernest Hemingway, painted in the 1930s. Peirce is the bearded figure in the upper left; Hemingway is seated at the bar.

Although Peirce's style changed several times over the years, it was basically representational, colorful, and lusty, clearly denoting his Rabelaisian love of life. A longtime friend of Ernest Hemingway, of whom he painted the cover picture for Time magazine in 1937, Peirce was once called "the Ernest Hemingway of American painters." To which he replied, "They'll never call Ernest Hemingway the Waldo Peirce of American writers." Of his death, Time wrote: "Waldo Peirce, 85, American Impressionist painter, a bewhiskered giant of a man noted as much for his exuberant lifestyle as for his bold, spontaneous art; of pneumonia... Peirce lived with all the verve and gusto of his lifelong friend and traveling companion Ernest Hemingway, even to the point of taking four wives and running with the bulls in Pamplona. His splashy, sensuously colored paintings, said one critic, 'smell of sweat and sound like laughter.' "[3]

Education

Peirce was the son of Maine timber barons who were interested in the arts; they encouraged, as well as subsidized, the artistic and scholarly bents of both Peirce and his older brother, Hayford, well into their adulthood. Peirce attended Phillips Academy, the preparatory school in Andover, Massachusetts, where he was class of 1903. From there he went to Harvard, to join his more studious brother. Peirce was class of '07 but was a lackluster student who "majored in pool" and did not graduate until possibly two years later.[4] A large man for his time, he was "drafted onto the Harvard football team", he said, solely because of his size, and Hemingway liked to tell stories of Peirce's strength.[5] Peirce himself was more modest: "My fatality is to look strong.... However, looking strong is more impressive than being strong, so what the devil, if Ernest has a good story let him stick to it."[6] Yet, writes Margit Varga, one of Peirce's biographers, John L. Sullivan, the famous heavyweight boxer known as "the Boston Strongboy", "once visiting Bangor, had suggested that Waldo, because of his magnificent physique, become a prize fighter. That had been before Waldo entered Harvard."[7]

Europe and World War I

Peirce lived mostly abroad from 1910 to 1931, generally in Paris, but with lengthy stays in Tunisia and Spain. He began his painting career by studying at the Académie Julian, then spent time in Segovia, Spain, with the Impressionist Ignacio Zuloaga. Here he married a fellow student, Dorothy Rice, the daughter of a New York financier, whom he had met in Switzerland. Peirce, who was also known for his bawdy doggerel, later mocked his pretentious mother-in-law by penning: "When Dorothy dropped from her mother's womb, Forty reporters were in the room." His early artistic endeavors were not particularly successful in either Paris or in New York, where, in 1915, he paid to have his works exhibited in a New York City show that also included John Sloan, George Bellows, and Edward Hopper, all artists whose reputations have outlived Peirce's.

World War I began in 1914, and Peirce made at least two attempts to enlist in the French army. Failing that, he joined—two years before the United States entered the war—the American Field Service, a volunteer ambulance corps that served on French battlefields; he spent most of the rest of the war as an ambulance driver or working for the Red Cross. For his efforts, the French government gave him the Croix de Guerre for bravery at Verdun.

"The Lost Generation" and the 1920s

1920's Paris was famous for being home to many members of the so-called "Lost Generation": American literary and artistic personalities who had been scarred and disillusioned by the horrors of the war just ended. Now living in "a magnificent apartment and studio overlooking the Seine",[8] Peirce mingled with Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, John Dos Passos, and Ezra Pound, as well as other notables such as Sylvia Beach, Ford Maddox Ford, Archibald MacLeish, and James Joyce, once advising Nora Joyce that "Jim should leave out the swear words," surely tongue-in-cheek advice coming from a man who was noted for his own pungent vocabulary. Peirce also had a keen eye for the works of other painters; sometimes using money borrowed from his mother in Bangor, he made some timely purchases: a Renoir for $600, a Cézanne for $2,000,[9] and a Modigliani.

Divorced by his first wife in 1917, Peirce married another American, Ivy Troutman, an actress he had met in Paris, in 1920, but was separated from her by the end of the decade. He was also travelling back to the United States for shows and exhibitions throughout the 'twenties and in New York City met Alzira Boehm, a sculptor, whom he would marry in 1930. Critics were beginning to review his works favorably and he was selling paintings, although not enough to live on—his parents in Maine continued to subsidize him.

When and where Peirce first met Ernest Hemingway is not known, but in July of 1927 they spent two weeks together in Pamplona, Spain, without their wives. A few months earlier, Peirce had written his mother:

"Did you read The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway? A good novel of the Latin Quarter and the derelicts of the war—that lost generation—they are real people, friends or acquaintances of mine... I tried to get Hemingway to dinner with all his characters of the SAR... One of the year's bestsellers... They all got drunk even as in the book and [they] didn't show up."[10]

The public figure

It was also during the 'twenties that Peirce began to emerge as an engaging public figure. A brief New Yorker profile following a successful one-man show in New York emphasized, not his art, but "The large, grotesquely unkempt man with the unforgettable scraggly beard, seen periodically on Fifth Avenue of recent years." [11] Various versions of his most famous episode also circulated. This was supposed to have occurred in 1911, two years after his graduation from Harvard. He and a former classmate, John Reed, the American communist who is buried in the Kremlin walls, signed up to take a cattleboat from Boston to England. As the ship was leaving Boston Harbor, Peirce decided that the accommodations were not to his taste. Without a word to anyone, he jumped off the back of the ship and swam several miles back to shore. Reed was then arrested by the ship's captain for the murder of his vanished traveling companion and thrown into the brig. When the freighter eventually arrived in England, Peirce was at the dock waiting to greet his friend Reed—he had dried himself off and taken a faster ship to England. Other versions have Peirce being plucked out of the ocean by the Lusitania and eventually arriving in England to find Reed being tried in an English court for murder.[12] Every version has elaborate supporting details, but whether any of them is actually true is open to question.

Another story is recounted by the American humorist H. Allen Smith in a 1953 book called The Compleat Practical Joker. In it, the playwright Charles MacArthur recalls his favorite practical joke. Its perpetrator was Peirce, who was living in Paris at the time and made a spontaneous gift of a very small turtle to the lady who was the concierge of his building. The lady doted on the turtle and lavished it with care and affection. A few days later Peirce substituted a somewhat larger turtle for the original one. This continued for some time, with larger and larger turtles being surreptitiously introduced into her apartment. The concierge was beside herself with happiness and displayed her miraculous turtle to the entire neighborhood. Peirce then began to sneak in and replace the turtle with smaller and smaller ones, to her bewildered distress.

Peirce was also known for his Rabelaisian poems and ballads. Yet another Harvard classmate, Maxwell Perkins, the famous Scribner's editor linked to Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Thomas Wolfe, considered publishing Peirce's verse but was overruled by Charles Scribner himself because of its risqué nature. One notorious poem, concerning the majestic bosom of Peirce's first mother-in-law, was privately printed in 1931, and was, apparently, recited for many years at certain meetings of the exclusive Knickerbocker Club in Manhattan. The first verse reads:

Breasts and bosoms have I known,

Of various shapes and sizes,

From poignant disillusionments

To Jubilant surprises,

But none incited me to sweat,

Recoil, shrink, cringe, nay shudder,

As the sight of Mrs Isaac Rice's

Prehistoric utter.

Later, in the 1930s, Perkins advanced Peirce $500 to write his autobiography, but it was never completed and Peirce returned the money.

The 1930s, the pinnacle of success, and domesticity

The painter, his art-historian brother, and their respective wives before a night at the Bangor opera circa 1938. "He was a local, beloved celebrity, if an eccentric one.... Kids in the city would cry, 'There goes Whiskers-the-Artist.' "[13]

Alzira, Peirce's third wife, gave birth to twin boys in Paris in 1930 and the following year the family moved to a house in Bangor directly across the street from the Cedar Street home in which Peirce had grown up. After 20 years in Europe, he never again lived there. He began to paint innumerable pictures of his growing family, of country scenes in Maine, and of flowers. His career reached its pinnacle of success during the thirties, with shows, exhibitions, favorable reviews from critics in America and Europe, and increasing sales to museums. "At the height of Peirce's public renown (the 1930s) he was seen as '...one of America's ablest and most representative artists'....provincial acclaim alone it was not: Peirce shared, and was given equal coverage in the same issue (January, 1939) of The London Studio with Matisse and Picasso, the giants of the pace-setting School of Paris."[14] Comparisons were frequently made between Peirce and the French masters Matisse and Renoir. "A similar joyfulness... often permeates their paintings," one critic wrote years later,[15] sometimes, however, becoming a " 'taste for easy sentiment' which James Mellow states 'often flawed Peirce's work and the work of the thirties regionalists in general.' "[16]

Sometimes accompanied by his family, Peirce visited Hemingway for extended stays in Key West, Florida, where they frequently went deep-sea fishing, occasionally along with another friend from the years in Paris, the now-famous writer John Dos Passos. In a letter written in the mid-1930s, Hemingway described a visit by the Peirce family to his home:

Waldo is here with his kids like untrained hyenas and him as domesticated as a cow. Lives only for the children and with the time he puts on them they should have good manners and be well trained but instead they never obey, destroy everything, don't even answer when spoken to, and he is like an old hen with a litter of apehyenas. I doubt if he will go out in the boat while he is here. Can't leave the children. They have a nurse and a housekeeper too, but he is only really happy when trying to paint with one setting fire to his beard and the other rubbing mashed potato into his canvasses. That represents fatherhood."[17]

Over the years, Peirce did numerous paintings and sketches of Hemingway; Kid Balzac, an earlier picture from 1929, hangs in the Ernest Hemingway Collection room of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston.[18] In 1937, when Hemingway's To Have and to Have Not was published, Peirce was commissioned by Time magazine to paint the cover picture. "In the portrait, reminiscent of the style of Matisse," writes Gallagher, "Hemingway's face is oddly shaped, peering intently upon a fishing line."[19] In spite of Peirce's increasing financial success as an artist in the 1930s, however, he was still at least partially supported by his father across the street. When his father finally died in 1936 at the age of 88, he left, for the deepest days of the Great Depression, a very substantial estate: $1.3 million—in today's dollars, more than $13 million.[20] Waldo and his two siblings shared the estate equally, so Peirce became a wealthy man for the rest of his own long life.

The 1940s and beyond

Peirce remained an important figure in American art during the 1940s, but interest in his kind of representational art began a precipitous decline after World War II as the new abstract expressionism typified by Jackson Pollock suddenly shifted the center of the art world from Paris to New York. A brief Time magazine article of July 31, 1944, noted that:

Waldo Peirce, grey-bearded, booming impressionist painter, journeyed from Bangor, Me. to Manhattan to receive his $2,500 first prize in Pepsi-Cola's Portrait of America painting contest, first business-sponsored art competition to be judged by prominent artists and esthetes (including Rockwell Kent, Fernand Leger, Alexander Brook, Reginald Marsh, Max Weber). Peirce's prizewinner: a radiant Maine Swimming Hole. Peirce's comment: "I've already spent the money. ... I like Pepsi-Cola with rum in it.... Now maybe I'll even drink some straight."

Already the father of three children, at the age of 62 Peirce married his fourth, and last, wife, Ellen Larsen. He moved his household from Pomona, New York, to a large Victorian house in the small coastal town of Searsport, an hour's drive south of Bangor, and began to raise two more children. Wintering occasionally in Tucson, Arizona, with an apartment in New York City and another old seaside house in Newburyport, Massachusetts, Peirce was much less the public figure he'd been for a number of years and his artistic reputation slowly dwindled away. He and Hemingway had drifted apart for a number of years, but met for the final time in Tucson, Arizona, in March 1959. Peirce received a Doctorate of Art from Colby College in Maine, painted unceasingly, particularly pictures of his family, and remained a robust and larger than life figure for many years until his death in Newburyport.

Peirce's older brother, Hayford, was a noted authority on Byzantine art, and his third wife, Alzira Boehm, originally a sculptor, eventually enjoyed a modest reputation as a painter.

Why has Peirce vanished from the art scene?

Today it is hard to find a mention of Peirce in any recent history and/or appraisal of American art. Although mentioned briefly in Samuel Eliot Morison's three-volume Oxford History of the American People, even there his name is misspelled in the text and is inexplicably omitted from its otherwise exhaustive 52-page "cumulative index".[21] Morison, moreover, was Peirce's longtime friend and godfather to his twins. The public's taste in art changes over time, of course, but why has this once-prominent artist now become nearly invisible? One suggestion is that he was never closely associated with any particularly prominent school of art, such as the Cubists, or the Ashcan, which might have helped maintain his reputation. "Over his lifetime," writes Gallagher, "Waldo's technique and style changed, reflecting various influences. Early on, it was the Impressionists, especially Cézanne. His paintings of multipattern interiors, clothing, and carpets reveal a strong Matisse flavor. His roly-poly children suggest a taste for Renoir. Later in life, he could be placed with the Regionalists, who painted scenes of everyday life, play, and work."[22]

Hemingway, however, was concerned that once Peirce became a father he became overly preoccupied with his family.

As a painter I think he is one of the finest in America.... As a parent and trainer of children he is the absolute bloody worst in the world. His children's idea of good clean fun is for one of them to hit Waldo on the head with a beer bottle, while the other sets fire to his beard. Waldo smiles happily and says, "Well, pretty soon they'll be in school." It can't come too quick for me or the good of American painting.

Another possible explanation was given by his sister-in-law, Polly Brown Peirce.

She felt that Waldo had too much money to be a great artist. While Polly always admired Waldo's full-time devotion to his art, in spite of the fact he didn't really have to do it, she felt he could have been greater if financial reasons had forced him to focus more on the commercial side of art or look a little deeper into his soul.[23]

Another, more prosaic, reason may be that he simply painted too much, too quickly, and that the market became over-saturated with his works. His output was enormous and he frequently painted the same picture over and over. Several copies, for instance, of his well-known Sloppy Joe's painting are extant. The same is true of his portrait of Hemingway that graced the cover of Time. For many years he also wrote hundreds of letters that were mailed in envelopes colorfully illustrated by a quick watercolor; he did the same with postcards. Market forces dictate that scarcity of any commodity generally increases its value. In Peirce's case, however, his works are far from scarce and may well be over-abundant.

Possible resurgence of interest in Peirce?

Although most of Peirce's works that have appeared for sale at auctions over the last ten years or so have sold for modest prices of between $2,000 and $15,000, at least two of his paintings have gone for substantially more. In 2007, the Barridoff Galleries sold Swimming Mosman Park for $48,000.[24] Two years earlier the Eric Nathan Auction Company had sold a Sloppy Joe's for what apparently is a record for a Peirce work, $75,600. [25]

Museums and collections that own works by Waldo Peirce

Sources: AskArt.com[26] and Waldo Peirce, A New Assessment "[27]

- Addison Gallery of Ameican Art, at Phillips Academy[[5]]

- Arizona State University Art Museum [[6]]

- Brooklyn Museum of Art [[7]]

- Butler Institute of American Art [[8]] [[9]]

- Carnegie Museums of Pittsburg/Carnegie Institute [[10]]

- Colby College Museum of Art [[11]]

- Columbus Museum of Art–Ohio [[12]]

- Encyclopedia Britannica Company

- Farnsworth Art Musueum [[13]]

- Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, at the University of Minnesota[[14]]

- Georgia Museum of Art, at the University of Georgia[[15]]

- Hirschorn Collection

- James A. Michener Foundation

- Metropolitan Museum of Art [[16]]

- National Portrait Gallery, at the Smithsonian Institution [[17]]

- Newark Museum [[18]]

- Ogunquit Museum of American Art [[19]]

- Parrish Art Museum [[20]]

- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts [[21]]

- Pepsi-Cola Company

- Portland Museum of Art [[22]]

- Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery [[23]]

- Smithsonian American Art Gallery [[24]]

- Southern Oregon State College

- University of Arizona Museum of Art [[25]]

- University of Maine Museum of Art [[26]]

- University of Michigan Museum of Art [[27]]

- Upjohn Company

- Washington State College

- Whitney Museum of American Art [[28]]

References

- ↑ In 1945 Life magazine called him "one of American's most famous painters"—Waldo Peirce: A New Assessment 1884-1970, University of Maine at Orono Printing Office, University of Maine, 1984, page 37

- ↑ A 1945 biography, Waldo Peirce, American Artists Group, Monograph Number 5, New York, 1945, notes on the last, unnumbered page of the booklet that Peirce was already "represented in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum, Whitney Museum, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Addison Gallery of American Art, Brooklyn Museum, University of Arizona, State College of Washington, Encyclopaedia Britannica Collection, Harvard University, University of Maine, University of Nebraska, Fransworth Gallery." Among the private collections mentioned were those of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Mervyn LeRoy, Paulette Goddard, Burgess Meredith, Ernest Hemingway, and John Marquand.

- ↑ Time, March 23, 1970.

- ↑ Some sources say 1908, others 1909. "He claimed he 'majored in pool,' playing upstairs at the Leavitt and Peirce Smoke Shop in Cambridge, where one can still find his comical, illustrated poem about the poolroom."—The Colors of Waldo, by William Gallagher, MD, Bangor Metro, December, 2005, page 33.

- ↑ Waldo Peirce, by Margit Varga, The Hyperion Press, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1941, page 38.

- ↑ Waldo Peirce, by Margit Varga, The Hyperion Press, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1941, page 38.

- ↑ Waldo Peirce, by Margit Varga, The Hyperion Press, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1941, page 38.

- ↑ At 77 rue de Lille, on the Right Bank—The Colors of Waldo, by William Gallagher, MD, Bangor Metro, December, 2005, page 35.

- ↑ Waldo Peirce: A New Assessment 1884-1970, University of Maine at Orono Printing Office, University of Maine, 1984, pages 28 and 29

- ↑ The Colors of Waldo, by William Gallagher, MD, Bangor Metro, December, 2005, page 35

- ↑ Waldo Peirce: A New Assessment 1884-1970, University of Maine at Orono Printing Office, University of Maine, 1984, page 33

- ↑ Waldo Peirce, by Margit Varga, The Hyperion Press, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1941, page 38.

- ↑ The Colors of Waldo, by William Gallagher, MD, Bangor Metro, December, 2005, pages36 and 37

- ↑ Waldo Peirce: A New Assessment 1884-1970, University of Maine at Orono Printing Office, University of Maine, 1984, pages 18 and 19

- ↑ Waldo Peirce: A New Assessment 1884-1970, University of Maine at Orono Printing Office, University of Maine, 1984, page 14

- ↑ The Rural America Waldo Peirce Saw, a 1970 article by James R. Mellow quoted on page 14 of Waldo Peirce: A New Assessment 1884-1970

- ↑ From The Private Hemingway, quoted in the New York Times, 15 February 1981.

- ↑ Kid Balzac at the John F.Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum[[1]]

- ↑ The Colors of Waldo, by William Gallagher, MD, Bangor Metro, December, 2005, page 37

- ↑ From the Bangor Daily News, circa 1937

- ↑ Volume 3, page 252, The Oxford History of the American People, by Samuel Eliot Morison, paperback edition, Mentor Books, New Signet Library, New York, 1972

- ↑ The Colors of Waldo, by William Gallagher, MD, Bangor Metro, December, 2005, page 37.

- ↑ The Colors of Waldo, by William Gallagher, MD, Bangor Metro, December, 2005, page 39.

- ↑ This picture can be seen at AskArt.Com [[2]]

- ↑ Information, including sale price, on approximately 85 works by Peirce is available for a fee at AskArt.Com [[3]]

- ↑ AskArt.Com[[4]]

- ↑ Waldo Peirce: A New Assessment 1884-1970, University of Maine at Orono Printing Office, University of Maine, 1984, page 44