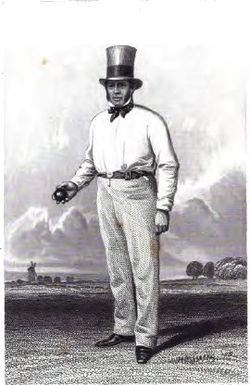

William Clarke

William Clarke (24 December 1798 – 25 August 1856) was an English professional cricketer from Nottingham who played for both the Nottingham Town Club and Nottinghamshire county teams from 1826 to 1855. In 1846, recognising the potential of the developing railway system, he formed the touring All-England Eleven (AEE) to play lucrative matches throughout the country. Clarke was an outstanding right arm spin bowler who persisted with an underarm action even though the roundarm style was introduced and became established in the early years of his career. Being a specialist bowler, he had only moderate ability as batsman (right-handed) and fielder.

Bricklayer to landlord

In his early teens, Clarke became an apprentice bricklayer, his father's trade. In 1818, he married Jane Wigley who was the landlady of the Bell Inn in Nottingham. They had six children. The youngest was Alfred Clarke who toured Australia and New Zealand with England in 1863–64. Sometime in the late 1820s, Clarke lost his sight in one eye after an accident which apparently happened in a ball game of some kind (possibly a fives match) at the Bell Inn. The disability did not prevent him from playing cricket and, from 1830, he was the captain of both Nottingham and Nottinghamshire. His wife died in September 1837 and, perhaps surprisingly given that it seems to have been a happy marriage, Clarke remarried only three months later. His second wife was Mary Chapman, ten years older than him, and she was the widowed landlady of the Trent Bridge Inn. Given all the circumstances, John Major suggests that the marriage may have been "a cosy one of convenience".[1] Clarke soon began using an adjacent field at his new pub for local cricket matches and, in 1841, this was formally opened as the Trent Bridge ground which was soon adopted as headquarters by the new Nottinghamshire county club. From 1899, it has been a regular Test venue.

Playing career to 1846

Clarke had been involved with the Nottingham town club from 1816 but it was not until 1826 that he played in a match now designated first-class. Throughout his career, there were never more than thirty first-class matches in any one season. County cricket had no formal organisation then and the majority of top-class matches were arranged on an ad hoc basis. At the time of Clarke's death, there were just four recently founded county clubs (including Nottinghamshire) and international cricket had not yet begun. So, although Clarke had already been a top-class player for several years, it was not until July 1826 when Nottingham travelled to the Darnall New Ground in Sheffield for a game against the combined Sheffield and Leicester team that his "first-class career" is deemed to have begun. His "debut" did not go well for him because Sheffield & Leicester won by an innings and 203 runs.[2] Clarke took five for 161 in the S&L innings of 379 which was dominated by the Yorkshire batsman Tom Marsden who scored 227, a massive score for the time (the then world record was 278 by William Ward for Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) v Norfolk at Lord's in 1820).

Clarke did not make his first appearance at Lord's until July 1836 when he took part in a South v North match which the North won by 6 wickets.[3] That was the North's first victory over the South but Clarke did not bowl as conditions favoured the fast bowlers Sam Redgate and Tom Barker. In 1844, Clarke went to Canterbury for the annual cricket festival and represented England against Kent. He had an outstanding match with six for 30 and six for 26, enabling England to win by 52 runs.[4] Nottinghamshire at the time were struggling financially and, in 1845, Clarke decided to seek remuneration elsewhere. Leaving the pub in his family's care, he went to Lord's and joined MCC as a ground staff bowler, where he was a colleague of William Lillywhite. Bowling together, they were a formidable combination as in the 1847 Gentlemen v Players match at Lord's when Clarke (then aged 48) and Lillywhite (55) took all twenty Gentlemen wickets between them, the Players winning by 147 runs.[5]

The All-England Eleven

In August 1846, Clarke embarked on the venture for which, as "Old Clarke", he is famous. MCC had just begun an economy drive and had reduced their match fee, which naturally caused discontent among the players. Realising the potential for a travelling "circus" team that the new railways provided, Clarke decided to act. The MCC season always ended in early August because the "gentlemen" wanted to be off to the grouse moors for their shooting season. With a good six to eight weeks of the full cricket season to go, Clarke assembled what he called the All-England Eleven (the AEE) to play three exhibition "odds" matches in the North of England against 20 of Sheffield, 18 of the Manchester Cricket Club and 18 of Yorkshire. Teams called England had frequently been assembled for over a century but it was rare that they deserved the name. Clarke's team undoubtedly did because, besides Clarke and Lillywhite, the all-star squad included Alfred Mynn, Fuller Pilch, Nicholas Felix, William Hillyer, George Parr, Joe Guy, Jemmy Dean, William Denison and Will Martingell. The tour was a great success, although the AEE lost to Sheffield, and Clarke was careful to pay his players marginally better than MCC could then afford. He kept the bulk of the profits himself. More big names were recruited in future seasons, including John Wisden, and the itinerary expanded as the fame of the venture became widespread and clubs from all over the country sent invitations, communication and fixture arrangement ably facilitated by the new penny post.

In 1848, Clarke resigned from MCC and became the AEE's full-time organiser. By 1851, he had a programme of 34 matches. There was conflict with MCC although the problems, as MCC saw them, were largely of their own making through self-indulgence and complacency. Nevertheless, Clarke was happy to recognise a need for the prestigious North v South and Gentlemen v Players fixtures and he made sure that the AEE players were available for those. Obviously, there was a business consideration there too because, when an AEE player made the news with an outstanding performance in one of the classic matches, that increased his market value when he played for the AEE. By 1852, however, Clarke's profiteering was causing unrest in the ranks and some players told him they deserved a larger share of the profits. Clarke refused and the AEE splintered with Dean and Wisden creating the United All-England Eleven (the UEE) as a rival enterprise.

Clarke's legacy

Clarke remained active till his death, aged 57, in August 1856. Parr succeeded him as the AEE organiser and, at first, intended to continue his policies. Pragmatically, however, Parr realised that change was necessary and, in July 1857, agreed with Dean and Wisden to stage a match between the two elevens at Lord's. This became an annual event and, in 1859, twelve players from the two elevens (six apiece) formed the first-ever England touring team, which went to North America. This was the prelude to England's long-term future as an international team, especially after the arrival of Test cricket in 1877. All of that, and not forgetting Trent Bridge, is the legacy of William Clarke.

William Caffyn said that Clarke had done more than anyone else to popularise cricket. In his history, Harry Altham said that Clarke was "one of certain figures who, in the history of cricket, stand like milestones along the way".[6]

MCC recognised Clarke's contribution to cricket, especially the coaching and encouragement he gave to young players, but with reservations. Pelham Warner, always the MCC apologist, said: "It is a pity that Clarke's great services to cricket were marred by an over-tenacity in asserting his rights, real or otherwise".[7] That comment in 1946 is a classic example of the old pot and kettle syndrome because the Australians had long ago said the same thing about MCC's all-time hero, WG. In 1874, an Australian newspaper editor declared: "We in Australia did not take kindly to WG. For so big a man, he is surprisingly tenacious on very small points. We thought him too apt to wrangle in the spirit of a duo-decimo lawyer over small points of the game".[8]

Notes

- ↑ (quote) Major, p. 171.

- ↑ (scorecard) Sheffield & Leicester v Nottingham, 1826. ESPN Sports Media Ltd.

- ↑ (scorecard) South v North, Lord's, 1836. ESPN Sports Media Ltd.

- ↑ (scorecard) Kent v England, 1844. ESPN Sports Media Ltd.

- ↑ (scorecard) Gentlemen v Players, Lord's, 1847. ESPN Sports Media Ltd.

- ↑ (quote) Altham, p. 79.

- ↑ (quote) Warner, p. 46.

- ↑ (quote) Birley, pp.111–112

Sources

- Altham, H. S.: A History of Cricket, Volume 1 (to 1914). George Allen & Unwin (1962).

- Birley, Derek: A Social History of English Cricket. Aurum (1999).

- Major, John: More Than A Game. HarperCollins (2007).

- Swanton, E. W. (editor): Barclays World of Cricket, 3rd edition. Willow Books (1986).

- Warner, Pelham: Lord's, 1787–1945. Harrap (1946).