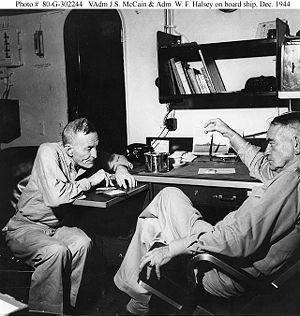

William Halsey

William F. "Bull" Halsey (1882-1959) was a admiral of the United States Navy, a colorful and inspirational combat leader in the Second World War. As a task force and area commander, there is little question that he reinstilled fighting spirit in exhausted U.S. forces, as well as fixing command problems and providing desperately needed support for the Guadalcanal campaign. He was also quite controversial in terms of his ability at the level of fleet command, especially at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, and later when the Third Fleet was in typhoons. One of his most authoritative biographers, E. B. Potter, had begun his work tending to believe that argument, but eventually saw him as

a man not without shortcomings but with qualities of leadership, courage, judgment, good will and compassion that utterly outweigh his faults.[1]

He detested the Japanese and made remarks that may seem extreme by today's standards, but not those of the time. They also galvanized U.S. forces concerned that various top leaders were not fighters.

As Halsey points out in his autobiography, "Bull" was the nickname of the press corps, not the Navy. Named for his father, he was first called "Old Bill", then "Bill" in the Navy, and "more recently I suppose it is inevitable for my juniors to think of me, a fleet admiral and five times a grandfather, as "Old Bill" Now that I am sitting down to my autobiography, it is Bill Halsey whom I want to get on paper, not the fake, flamboyant "Bull.""[2] Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox told a story of two enlisted men on Halsey's flagship. When one said "Halsey? I'd go through hell for that old son of a bitch!" A finger jabbed into his back: "Young man, I'm not so old!"[3]

Early life and career

Born into a Navy family, he graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1904, specializing in torpedo warfare. "He commanded the First Group of the Atlantic Fleet's Torpedo Flotilla in 1912-13 and several torpedo boats and destroyers during the 'teens and 'twenties. Lieutenant Commander Halsey's First World War service, including command of USS Shaw (Destroyer # 68) in 1918, was sufficiently distinctive to earn a Navy Cross."

In 1922-25, Halsey served as Naval Attache in Berlin, Germany and commanded USS Dale (DD-290) during a European cruise. [4]

Preparing for WWII

Halsey recognized, earlier than other officers, the significance of naval aviation. In 1932, he left destroyer duty, in which he had spent all but one year of his sea duty. He first attended the Naval War College, and then the Army War College, which was then in Washington, DC and focused on the level of national strategy.

Entering aviation

Ernest J. King, then head of the Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics, offered him command of the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) if he would qualify as aircrew by taking the aviation observer course. He did not immediately agree but asked his wife's opinion, and she said she would agree if Admiral William Leahy, then head of personnel for the Navy, agreed. Leahy blessed the idea.

Arriving at the air training center at Pensacola, Florida in July 1934, he changed from the observer to the pilot curriculum. Much older than the usual student pilot, he noted that "my eyes could not pass the tests for a pilot, and how I managed to be classified as one, I honestly don't know yet, and I'm not going to ask." [5]

After his certification of a pilot, he indeed took command of Saratoga, until 1937, when he became commandant at Pensacola. He was selected as a rear admiral in 1937, waiting for an opening fifteen months later.

Force command

In May 1938, he took command of Carrier Division 2 and gained experience in multiple-ship operations. He encouraged discussions of carrier tactics, and appointed a squadron commander, Miles Browning, as his deputy. Thomas Moorer, a future Chief of Naval Operations and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said Halsey "had a knack of involving everyone in the discussion." Browning, however, was aloof and condescending. [6] Halsey's loyalty to Browning would be an embarrassment in later years.

In the major fleet problem of early 1939, Halsey's division was under the command of Ernest J. King, then Commander, Aircraft, Battle Fleet, known to be a highly ambitious perfectionist. Halsey was an apt pupil of King, but more than once felt the lash of King's explosive temper. King actually held him in high regard, which was to continue through WWII.

Promotion to Commander of Carriers

Halsey introduced a number of new communications procedures, which became standard, as division commander. On 13 June 1940, he became Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force, with the temporary rank of vice admiral, also commanding Carrier Division 2. In the summer of 1940, he first had the opportunity to work with radar on real warships, and was stunned by its potential.

If had to give credit to the instruments and machines that won us the war in the Pacific, I would rate them in this order: submarines first, radar second, planes third, bulldozers fourth.[7]

On 1 February, Adm. Husband Kimmel replaced Admiral James Robertson as commander of he Pacific Fleet. Kimmel was Halsey's classmate and friend. He was pleased when another old friend, Raymond Spruance, took command of Halsey's cruisers in mid-Sepember. Intelligence showed more and more Japanese preparation, and Halsey attended a November 27 conference on reinforcing Wake Island. His carrier force was ordered to deliver them, and was thus safely out of port when Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Reinforcing Wake

The Wake reinforcement was designated Task Force 2. Once they were clear of the local area, he split off the USS Enterprise (CV-6), three heavy cruisers and nine destroyers, and designated them Task Force 8. Task Force 2 would feint away from TF 8, which, without the older battleships, was capable of 30 knots. Before departing, Halsey asked Kimmel, with respect to the Japanese sensitivity about waters they considered in their sphere of influence, "How far do you want me to go?"

Kimmel replied, "Goddammit, use your common sense!" Halsey later said "I consider that a fine an order as a subordinate ever received."[8]

When TF8 was out of signal range of TF2 and Pearl, he had the Enterprise's captain, George Murray, issue Battle Order No. 1, which included:

- The Enterprise is now operating under war conditions

- At any time, day or night, we must be ready for instant action

- Enemy submarines may be encountered.

He ordered all aircraft armed with live ammunition, and to sink any ship encountered and shoot down any aircraft, having confirmed no Allied shipping was in the area. This was a shock to the task force staff, as only three knew the real mission. His operation officer, William Buracker, confirmed he authorized it, and said "Goddamit, Admiral, you can't start a private war of your own! Who's going to take the responsibility?"

Halsey, who had decided war would come in days or hours, and that the delivery of the aircraft was essential, resolved to destroy any Japanese reconnaissance forces before they could report his position. They delivered the planes and turned back to Pearl on December 4, planning to reenter on December 7, but was delayed by the need to fuel destroyers. [9]

Pearl Harbor attacked

Early on the morning of 7 December, the task force sent 18 of it aircraft ahead to land at the Ford Island naval air station at Pearl Harbor. When the first report of an air raid on Pearl Harbor was received, Halsey realized that the base had not been notified about his incoming aircraft, and assumed that U.S. antiaircraft gunners were shooting at them. As he rushed to inform Ford Island, the first alerts began to arrive, specifically identifying Japanese aircraft at 0823. Kimmel, at 0923, broadcast that a state of war existed with Japan, and, at 0921, ordered TF3, a heavy cruiser and destroyers, and TF 12, the USS Lexington and screen to join Halsey. All ships at Pearl that were still operational were ordered to sortie as TF 2 and join Halsey, giving him operational control of every ship at sea. Potter quoted a comment from Halsey, years afterward, "I have the consolation of knowing that, on the opening day of the war, I did everything in my power to find a fight." Potter's opinion was that even after reflection, "it did not occur to him that it might have been a mistake to expose America's slender carrier forces to ruinous odds."[10]

Five of the eighteen Enterprise aircraft indeed were shot down by U.S. gunners. At 1330, the Department of the Navy broadcast the declaration of war. Enerprise and her destroyers sent out patrols into the night, but found nothing. Halsey himself was not unhappy he did not meet the Japanese force, because he had only cruisers to oppose battleships. Air strikes, especially when the Lexington joined him, was a possibility, but he had limited reconnaissance resources and could not find the force. By evening of the 8th, he returned to Pearl.

On seeing the wreckage, he muttered a phrase that would resonate through the fleet: "Before we're through with them, the Japanese language will be spoken only in hell!" [11]

Senior command

His senior command experience was at three levels:

- Pearl Harbor to 28 May 1942: task force command; then on the sick list

- 18 October 1942 to 15 June 1944: commander of the South Pacific Area

- 16 June 1944 to end of war: Third Fleet command

Task Force

When Halsey returned to Pearl on 31 December, after escorting a convoy, he reported to Chester W. Nimitz, who had just taken formal command after Kimmel asked for relief. Halsey and Nimitz had known one another at the Naval Academy, but had not served together. In the interest of morale and continuity, Nimitz had retained Kimmel's staff.

On 8 January, Halsey and Spruance attended a CincPAC meeting at which Adm. Pye, commanding the Battle Force, had developed a limited counterattack plan, which Nimitz and his operations officer, Charles "Soc" McMorris, liked. Nimitz was not an aviator, but a submariner, and had difficulty in responding to officers who opposed risking the carriers. Halsey supported Pye's plan and volunteered to lead the attack. Later, Nimits said of him, "Bill Halsey came to my support and offered to lead the attack. I'll not be a party to any enterprise that can hurt the reputation of a man like that."[12]

Raiding the Marshalls

While large-scale raids and certainly any amphibious landings were out of the question, a spoiling raid against the Marshall Islands could slow Japanese expansion. In January 1942, Fletcher's cruiser-destroyer Task Force 17 (TF 17) sailed from San Diego to reinforce the Marine garrison at Samoa. Vice Admiral William Halsey, commanding carrier Task Force 8, joined the escort, which, after delivering the Marines, would conduct strikes in the Marshall Islands.[13]

A task force centered on the Enterprise and three heavy cruisers sortied on the 20th, to rendevous with Frank Jack Fletcher's Yorktown force on the 20th. Linkup did not happen until the 23rd.

Doolittle Raid

Halsey commanded the naval task force that first brought the war to the Japanese homeland, the Doolittle Raid of April 1942. This operation is sometimes called the Halsey-Doolittle raid.[14]

He made a difficult decision when a Japanese patrol boat discovered the two-carrier force, 650 miles from the Japanese coast. While it had been planned to launch the Army B-25 Mitchell bombers 400 miles from Japan, he balanced the risk to a major part of the operational U.S. carriers, and launched from 650 miles. This decision is generally regarded as an appropriate balancing of alternatives.

Battle of Midway

Halsey was medically unable to lead forces at the Battle of Midway due to disabling skin disease. He did, however, recommend Raymond Spruance as his replacement.

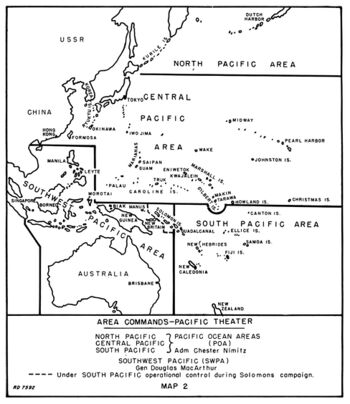

South Pacific Area

After being medically approved to return to duty, he was named to command a carrier task force in the South Pacific Area. Since the ships were still being readied, he began a familiarization trip to the area on 15 October 1942, arriving at the Noumea area headquarters on the 18th. After Pacific commander Chester W. Nimitz concluded that VADM Robert Ghormley had become dispirited and exhausted. As Halsey's aircraft came to a stop at Noumea, Ghormley's flag lieutenant met him before he could board the flagship, giving him a sealed envelope containing a message from Nimitz:

YOU WILL TAKE COMMAND OF THE SOUTH PACIFIC AREA AND SOUTH PACIFIC FORCES IMMEDIATELYHalsey was "apprehensive" because he "knew nothing about campaigning with the Army, much less with Australian, New Zealand, and Free French forces. Second, although I knew little about the military situation in the South pacific, I knew enough to know it was desperate...lastly, I was regretful because Bob Ghormley, whom I was relieving, had been a friend of mine for forty years."[15]

Carl Solberg, an intelligence officer on Halsey's staff, wrote that Halsey was kept ashore at Noumea, after his early task force leadership, to provide motivation for demoralized U.S. forces in the South Pacific. Once they began to operate independently, the new system of fleet command was instituted.[16]

Miles Browning was chief of staff, although Knox, King, and Nimitz all disapproved of him. In January 1943, he was assigned as captain of the Enterprise, but was relieved in April. Robert "Mick" Carney became permanent chief of staff in July.

During this period, Joe Bryan, a former editor of the Saturday Evening Post and a son of a friend of Halsey's, transferred to his headquarters. He wrote a series of biographical articles in the Post, and later would coauthor his autobiography.[17]

Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal, where a long battle was still active, was the most critical spot in his Area. While he had planned to visit it on the inspection trip, Nimitz had cancelled that stop, presumably to speed his relief of Ghormley. He was faced with an immediate decision: should there be another air base to supplement Guadalcanal's Henderson Field, which the Japanese were able to neutralize temporarily? The closest existing field was at Espiritu Santu, 600 miles away. Ghormley had planned to build an airport 200 miles closer, on Ndeni in the Santa Cruz Islands.

Archer Vandegrift, the Marine commander on Guadalcanal, said he could not spare anyone to build the Ndeni field. Halsey concluded that he could not decide the airfield issue without firsthand knowledge of Guadalcanal, so he asked Vandegrift to come to Noumea. The meeting, on 23 October, included Commandant of the Marine Corps Thomas Holcomb, Major General Millard Harmon, U.S. Army commander for the area; Major General Alexander Patch, commanding Army forces in New Caledonia; and "Kelly" Turner, Commander, Amphibious Force, South Pacific.

The next day, without Nimitz's permission, he cancelled the Ndeni operation and sent its resources to Vandegrift. Another issue had been that Turner, in charge of the ships supporting Vandegrift ashore, was interfering with Marine decisions. Halsey concurred with Holcomb that the commander of a landing force should be co-equal with the amphibious commander, which became the standard for future operations.[18]

Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

As Vandegrift returned to Guadalcanal, the Japanese launched a ground operation to recapture the field, and, from traffic analysis, it was learned that Japanese fleet elements were at sea, perhaps to reinforce a captured airstrip. Halsey ordered USS Enterprise' (CV-6) and USS Hornet to advance, under their group commander, Thomas Kinkaid, north of the Santa Cruz Islands. This would put them astride the path of any Japanese force coming from Truk.

In the early morning of 26 October, land-based patrol planes found the Japanese force, but their report made it to Halsey but not Kinkaid. Not realizing that Kinkaid was not ignoring the opportunity for an attack at dawn, but also not wanting to give tactical instructions to the local commander, Halsey broadcast the message:

ATTACK — REPEAT — ATTACKEventually, a search plane unit sent out by Kinkaid found the Japanese force and damaged the light carrier IJN Zuiho. Japanese search aircraft, however, launched an attack against the Americans, disabling the Hornet. A second Japanese attack damaged the Enterprise, while U.S. aircraft damaged a heavy cruiser and an aircraft carrier. Hornet, however, had to be abandoned. The Japanese finally sank her.

While the battle cost the Americans more in ships, the Japanese lost twice as many aircraft and pilots. This helped the ground troops hold the airfield.

- First battle, cruisers, 12-13 November

- Second battle, battleships, 14-15 November

Battle of Tassafaronga

30 November 1942

Second Solomons campaign

After Gudalcanal fell on 8 February 1943, Halsey's area forces moved to take the unopposed Russell Islands, on 21 February, to establish an airfield for attacks on Munda in New Georgia. Operationally, Munda defended Bougainville, Bougainville defended Rabaul, and Rabaul was the key of the Japanese Southern Pacific defenses.

The next logical base was on Woodlark Island, 200 miles from Bougainville and 300 miles from Rabaul. Woodlark, however, was in MacArthur's area, and Halsey could not operate there without MacArthur's consent. In early April, he flew to MacArthur's headquarters and met him for the first time. They formed an instant personal friendship, and Halsey consistently could work better with MacArthur than anyone outside MacArthur's command -- even to tell him "no" and have his comments taken seriously.

Interception of Yamamoto

Fleet command

In the Pacific War, the United States obtained much better usage of its warships than did the Japanese, as most of the combat vessels stayed at sea, with extensive logistical support. For the same set of ships, however, there were two command staffs. One set would conduct an operation from the flagship, while the other would stay on shore to plan the next operation. This policy was implemented by Admiral King on 15 March 1943.[19]

When the operating warships were under Halsey, they were designated United States Third Fleet. United States Fifth Fleet was their designation when commanded by Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance.

Halsey's chief of staff continued to be Robert "Mick" Carney.

Organization

Reflecting the alternation of the top command between Halsey (Third Fleet) and Spruance (Fifth Fleet), there were two major type-specific task forces that kept the same ships but changed numbers, not necessarily acting as an active command level in a particular engagement.

- TF 38/TF 58: Fast Carriers Pacific Fleet, under VADM Marc Mitscher and, later, John McCain Sr.

- TF 34/TF 54: Battleships Pacific Fleet, under VADM Willis Lee

As Halsey put it,

instead of the stagecoach system of keeping the drivers and changing the horses, we changed drivers and kept the horses. It was hard on the horses, but it was effective. Moreover, it consistently misled the Japs into an exaggerated conception of our seagoing strength.[20]

In this case, the horses, or carriers, battleships, and lighter ships primarily were distributed into four task groups.

On taking command on 18 June 1944, Halsey and his staff established offices at Pearl Harbor. Third Fleet began operations in the Solomons Islands.

First offensive

Third Fleet combat operations would focus on neutralizing the Japanese base at Rabaul and seizure of islands in the Solomons Islands. After Guadalcanal was secured, the next phase began on 30 June, first landing on the lightly defended Rendova Island, to emplace artillery to support the main landings on New Georgia by the Army's 43rd Division.

Japan, in response to the New Georgia attack, reinforced the next island in the Solomons chain, Kolombangara. Halsey's staff suggested bypassing it and landing the next island, Vella Lavella.[21] While the "island hopping" approach had been discussed, as early as the 1920s, by Earl Ellis, this was the first operation that actually did it. "It was perhaps the best example that he could be more than an instinctual fighter."[22]

Raids

Leyte Gulf

Halsey's decisionmaking was most controversial at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, in what unquestionably was confounded by divided command both in the battle, and at the theater levels of MacArthur and Nimitz. Halsey interpreted his orders from Nimitz to mean that the Third Fleet's primary role was to attack the Japanese fleet. His peer, Thomas Kinkaid, believed that Halsey had a role in protecting his Seventh Fleet, actually conducting landing operations, from that fleet. Kinkaid did not positively confirm his assumptions with Halsey, and they had no common commander to detect a misunderstanding.

Naval analysts differ on judging his actions in this largest naval battle in history, although more tend to believe he lost sight of the most important mission.[23]

Mission

Nimitz directed him to "cover and support" SWPA forces "in order to assist in the seizure of all objectives in the Central Philippines", and to "destroy enemy naval and air forces in or threatening the Philippines area." This was consistent with orders given to Spruance's Fifth Fleet in the Marianas operation.

An additional sentence in Halsey's orders, however, was "In case opportunity for destruction of major portion of the enemy fleet is offered or can be created, such destruction becomes the primary task". Friedman refers to Potter's biography of Nimitz, observing that the paragraph was not numbered as were the others, and not in the writing style of Nimitz or of Chief of Naval Operations Ernest King.[24] Nevertheless, in September, Halsey had written to Nimitz,

I intend, if possible, to deny the enemy a chance to outrange me in an air duel and also do deny him an opportunity to deploy an air shuttle[25] against me.

Inasmuch as the destruction of the enemy fleet is the principal task, every weapon must be brought into play and the general coordination of these weapons should be in the hands of the tactical commander responsible for the outcome of the battle [emphasis added]] .... My goal is the same as yours—to completely annihilate the Jap fleet if the opportunity offers.[26]

Nevertheless, it was not assumed that the enemy fleet would give that opportunity. Carl Solberg, an intelligence officer on Halsey's staff, wrote that Kinkaid and MacArthur "had planned the whole amphibious operation on the premise that the Japanese fleet would not come out to challenge a landing at Leyte...It was Nimitz's expectation as well: he had set the date of November 11 for the Third Fleet's attack on Jaoan...you did not lay out plans for attack on Tokyo...if you anticipated a major action with the Japnese fleet just beforehand."[16]

Referring to the underlined section, it is unclear who Nimitz would consider the tactical commander, and whether there was an overall tactical commander for the entire Leyte campaign. Twelve days before the landings, Nimits wrote to Halsey,

You are always free to make local decisions in connection with the handling of forces under your command. Often it will be necessary for you to take action not previously contemplated which may develop quickly and may not yet be available to me. My only requirement in such cases is that I be informed as fully and as early as the situation permits.[27]

Halsey, more aggressive than his friend Spruance, interpreted that in his own operation order: "If opportunity exists or can be created to destroy major portion of the enemy fleet, this becomes primary task.[28] This is the classic Mahanian goal, shared by Halsey's opponents, especially VADM Takeo Kurita.

Halsey also issued a battle plan, which he did not consider an order, saying that a surface gunfire force "will be formed as TF 34 under VADM Lee, Commander Battle Line. TF 34 will engage decisively at long ranges." It was his intention to have this treated as a warning order for the action if a surface engagement offered. As confirmation, he pointed out his subsequent radio message, "If the enemy sorties [through San Bernadino], TF 34 will be formed when directed by me."[29]

Halsey's analysis

Prior to submarines reporting major Japanese naval units in the Palawan Passage, Halsey had assumed the main strength of the Japanese strength was in its bases and "if it stayed holed up there, we planned to go and dig it out...[the report] was proof that a major movement was afoot...I ordered [the carrier task groups] to close the islands and to launch search teams in a fan that would cover the western sea approaches for the entire length of the chain. Experience had taught us that if we interfered with a Jap plan before it matured, we stood a good chance of disrupting it. The Jap mind is inelastic; it cannot adapt itself to an altered situation."[30] It is interesting to assume that Halsey had not automatically assumed the Japanese would make a strong naval response to the landings; this statement, from his autobiography, reflects his judgment towards the enemy.

Action off Samar

Confusion about Third Fleet mission and organization, however, was not restricted to Halsey's command. Both Nimitz and Kinkaid, however, were uncertain if TF 34 was operating as a single unit, generally assuming that it was, and called for Lee's assistance during the Action off Samar.[31] Lee might have formed TF 34 as Battle Line had Halsey engaged Ozawa's force with a surface gunfire action, but, as a result of the problems in San Bernadino Strait, Halsey called off that action.

Confusion between Halsey and Kinkaid, including Halsey's priority of attacking the Japanese carrier force, created a serious gap in U.S. forces at San Bernadino Strait, which was covered by only light vessels. When the Japanese fleet steamed through San Bernadino, the Action off Samar was decided by the desperate fighting of light vessels of the Seventh Fleet. Because the Americans were caught off-guard at San Bernadino because of Halsey's decision, and because of the serious losses the Americans suffered in the action off Samar which threatened the entire landing force had the Japanese pressed their advantage (which they did not), Halsey's decisions at the Battle of Leyte Gulf have come under much criticism. One of his critics, Barrett Tillman, wrote "In that dreadful hour, William Halsey proved himself unsuited to high command. He could not lead a fleet because he could not control himself." [22]

Typhoon Cobra

Typhoon Cobra, on 17=18 December 1944, caused more casualties and damage than the Battle of Midway. It prevented Third Fleet from carrying out scheduled raids on Luzon. A Court of Inquiry, headed by Vice Admiral John Hoover held on the 26th, Halsey testified that he was working with the best available weather information: "My aerologist informed me that in a study of past typhoons during the month of December, three out of four curved northward and eastward." In his defense, Halsey said he was working with the best weather information available at the time. said Halsey in testimony given at the inquiry. (Cobra moved to the northwest, and the fleet's attempt [32] The Court, however, put considerable blame on Halsey for not stopping the refueling operation, but Nimitz, in his endorsement of their findings, moderated it to "errors of judgment committed under the stress of war operations, and stemming from a commendable desire to meet military requirements." King further softened it by adding, after "judgment", "resulting from insufficient information" and changing "commendable desire" to "firm determination." In his autobiography, Halsey wrote of the typhoon, but not of the Court of Inquiry. [33]

The Second Typhoon

The Third Fleet suffered the effects of another typhoon, Typhoon Viper, on 5 June 1945. "Two times through a typhoon was too much for the navy to stomach, and the two storms almost cost Admiral Halsey his job. In effect, they did cost Vice Admiral John McCain Sr., TF38's commander, his job, although not until the war was over. Given his status as a popular here, Halsey retained his command but was closely watched thereafter."[34]

Operation Olympic

Had the invasion of Japan taken place, the Third Fleet, under Halsey and reinforced with the British TF37, would operate in a strategic role during Operation Olympic, the first phase landings against souther Japan. "Adm. Halsey's Third Fleet consisted of Vadm... J. H. Towers' Second Carrier Task Fleet (TF-38) and Vadm... H. Bernard Rawling's British Carrier Task Force (TF-37) and the usual collection of supporting vessels. In aggregate, Third Fleet could muster 17 fleet and light carriers, 8 battleships, 20 cruisers, and 75 destroyers. Some conception of the fleet's power can be formed from its record of 10,000 sorties in the month before Japan's surrender.

Third Fleet as the force assigned the task of softening up the objective area and isolating the battlefield would strike first. Between X-75 (28 July) and X-8 (23 October) the British and American fliers and gunners would attack widely scattered targets in the Japanese home islands in order to inflict the maximum damage on the Japanese air forces, disrupt communications between Honshu and Kyushu, and eliminate as much as possible of the remaining Japanese navy and merchant marine. Part of this effort would be diversionary British strikes on Hong Kong and Canton on X-45 (18 September) and X-35 (28 September)." [35]

Postwar

Shortly after the Japanese surrender, he requested retirement. He lowered his flag from the Third Fleet flagship on 22 November.

Promotion to Fleet Admiral

Halsey and Nimitz were the last Navy officer promoted to the special rank of Fleet Admiral, on 13 May 1946. Four such promotions were authorized for the Navy, although William Leahy was arguably a White House rather than Navy officer. King was reluctant to promote Halsey unless his peer, Spruance, was promoted as well, and sent Secretary of the Navy Forrestal a letter suggesting both of them, as well as four other senior admirals. Forrestal, after waiting several months, sent the letter to President Harry S Truman, who chose Halsey.[36]

Part of the difficulty was that Congressman Carl Vinson, the immensely powerful chair of Naval Appropriations, strongly liked Halsey,[37] and, depending on the source, either did not think as highly of Spruance or actively disliked him.

Rivalry between Halsey and Spruance was more a creation of the press than a reality. In a 1965 letter to E. B. Potter, Spruance wrote, "So far as my getting five-star rank, if I had gotten it along with Bill Halsey, that would have been fine, but if I had received it instead of Bill Halsey, I would have been very unhappy about it."[38]

Autobiography

His 1947 autobiography, which originally appeared as magazine installments, retained "a good deal of the original dictated narrative, sometimes at the expense of unity and in defiance of chronology. The result catches Halsey's personality strikingly; the reader almost seems to hear the admiral talking." [39]

The first installment brought him a furious response from a temperance society offended at his statement "there are exceptions, of course, but as a general rule, I never trust a fighting man who doesn't drink or smoke." More impactful, however, was his defense of Admiral Kimmel, which Halsey italicized:

In all my experience, I have never known a Commander in Chief of any United States Fleet who worked harder, and under more adverse circumstances, to increase its efficiency and to prepare it for war; further, I know of no officer who might have been in command at the time who could have done more than Kimmel did.[40]

Many officers were sympathetic to Kimmel, whom they regarded as a scapegoat. Halsey violated military custom about public criticism of George Kenney, MacArthur's air commander. While, by 1 November 1944, Kenney's forces had responsibility for the air defense of Leyte and surroundings, when the Japanese surged aircraft into the area, "Kenney could neither stop them nor protect our own troops and shippings. His fighters were useless against convoys, and he had few bombers."[41] Later, Halsey complained that he was unable to strike a concentration of Japanese ships in Brunei Bay, but could not due to "...Kenney's inability to give Leyte effective air support. I had to stand by and attend to his knitting for him. We found some compensation in sinking the convoys attempting to reinforce General Yamashita, commanding the Japanese forces on Leyte, but that too should have been Kenney's business."[42]

In the seventh installment, published on 26 July, he wrote about Leyte Gulf, citing divided command, saying of the Japanese Center Force at Samar, "I wondered how Kinkaid had let 'Ziggy' Sprage get caught like this", and of Kinkaid's demands for fast battleships, "That surprised me. It was not my job to protect the Seventh Fleet. My job was offensive, to strike with the Third Fleet." He blamed the southern run from Ozawa's force on Nimitz's garbled dispatch.[43]

Admiral King wrote to Halsey on 30 July, saying that he disliked the tenor of the installment, with respect to the overall command and to Kinkaid specifically. Replying on 12 August, Halsey wrote "I have given your letter and my article much thought and study, and have asked for and received counsel. I regret that your point of view and mine do not coincide."[43]

These comments also made an "implacable enemy" of Thomas Kinkaid, [44] in spite of writing, in the autobiography, "I have attempted to describe the Battle for Leyte Gulf in terms of my thoughts and feelings at the time, but, on rereading my account, I find that this results in an implication grossly unfair to Tom Kinkaid. True, during the action, his dispatches puzzled me, Later, with the gaps in my information filled, I not only appreciate his problems, but frankly admit that had I been in his shoes, I might have acted precisely as did he."[45]

References

- ↑ E. B. Potter (1985), Bull Halsey, U.S. Naval Institute, ISBN 0870211463, p. xiii

- ↑ William F. Halsey and J. Bryan III (1947), Admiral Halsey's Story, McGraw-Hill, p. 1

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, p. 146

- ↑ Fleet Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., USN, (1882-1959), Navy Heritage and Historical Command (formerly Naval Historical Center)

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, p. 56

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, pp. 139-140

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, p. 69

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, pp. 3-5

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 75-76

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, p. 12

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 79-81

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, pp. 37-38

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 85-95

- ↑ Halsey-Doolittle Raid on Japan, 18 April 1942, Navy Heritage & Historical Command

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 109-111

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Carl Solberg (1995), Decision and dissent: with Halsey at Leyte Gulf, U.S. Naval Institute, ISBN 1557509710, pp. 14-15

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, pp. 217-218 and 237-239

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, pp. 161-162

- ↑ Potter, Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 203-204

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, p. 197

- ↑ Potter, Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 223-227

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Barrett Tillman, William Bull Halsey: Legendary World War II Admiral, HistoryNet

- ↑ Kent S. Coleman (2006), Thesis Title: Halsey at Leyte Gulf: Command Decision and Disunity of Effort, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College

- ↑ Kenneth I. Friedman (2001), Afternoon of the Rising Sun: the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Presidio Press, ISBN 08911417567, 22.

- ↑ carrier-to-target-to-land

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, 279.

- ↑ The Battle of Leyte Gulf: 23-26 October 1944 (Bluejacket Books) by Thomas J. Cutler, p. 61. quoted by Friedman, 23.

- ↑ Com Third Fleet Operation Order 21-44 of October 3, 1944, quoted by Morison, 58.

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, 214.

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 210-211

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story 220-221.

- ↑ Steve Tarter (1 October 2002), "A force of nature: powerful as it was, in December 1944 the U.S. Navy's Third Fleet encountered an even more ferocious adversary--a typhoon called Cobra.", American History

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, pp. 322-324

- ↑ William T. Y'Blood (1987), The Little Giants: U.S. Escort Carriers against Japan, U.S. Naval Institute, ISBN 0870212753 pp. 400-402

- ↑ K. Jack Bauer (August 1965), "Olympic VS KETSU-GO", Marine Corps Gazette 49 (8)

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, p. 366

- ↑ Mike Coppock (May 2008), "Admiral Raymond Spruance: the Hit-First Warrior", Sea Classics

- ↑ Thomas B. Buell (1987), The quiet warrior: a biography of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, U.S. Naval Institute, p. 472

- ↑ Potter, p. 368

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, pp. 370-371

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, p. 230

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, p. 241

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Potter, p. 371

- ↑ Potter, p. 372

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, p. 227