World War Two in the Pacific: Difference between revisions

imported>Subpagination Bot m (Add {{subpages}} and remove any categories (details)) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "grand strategy" to "grand strategy") |

||

| (119 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}}{{TOC|right}} | ||

[[Image:Ww2-pacific.jpg|thumb|left|Scope of the Second World War in the Pacific]] | |||

[[Image: | '''World War Two in the Pacific''', called the '''Pacific War''' in Japan, was the part of [[World War II]] that took place in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and in East and South Asia between 1937 and 1945. There is no absolutely accepted starting date, but it is mos commonly accepted as e Japanese invasion of China ([[Second Sino-Japanese War]])) in 1937, but the most decisive actions took place after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the colonies of the U.S., the U.K., and the Netherlands in December 1941. | ||

The war, however, did not magically appear out of context, any more than World War Two in Europe clearly began on 1 September 1939. Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland were clearly precursors, and arguments can be made for proxies such as the [[Spanish Civil War]]. The rise of German [[National Socialism]] and Italian [[Fascism]] were necessary. The European conflict certainly was influenced by World War I and the [[Versailles Peace Treaty]], and not only World War I, but the [[Russo-Japanese War]] and [[First Sino-Japanese War]], as well as the [[Japanese militarism|Japanese militarism before World War Two]], all played a role. | |||

===Participants=== | ===Participants=== | ||

The major Allied participants were the United States and | The major Allied participants were the United States, Britain and is Commonwealth, including Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and India, and the Netherlands played significant roles. [[CBI|China played a major role]]. Mexico, DeGaulle's Free French Forces, Canada and other countries also took part, especially forces from other British colonies. The Soviet Union fought two short, undeclared border conflicts with Japan in 1938 and 1939, then remained neutral until August 1945, when it joined the Allies and invaded [[Manchukuo]] and Korea. | ||

The Axis states which assisted Japan included the Japanese puppet states of [[Manchukuo]] and the | The Axis states which assisted Japan included the Japanese puppet states of [[Manchukuo]] and the Wang Jingwei Government]] in China. [[Thailand]] joined the Axis powers under duress. Japan enlisted many soldiers from its colonies of Korea and Formosa (now called [[Taiwan]]). Some German submarines operated in the Indian Ocean. | ||

==Background== | |||

{{main|Japanese militarism}} | |||

Japan had a complex national desire to become a great power, which would require more resources. The initial approach, dating back to the nineteenth century, was exploitation of China,which, while not yet in outright civil war, had a national government under [[Chiang Kai-shek]] challenged by regional warlords and revolutionaries. These included [[Chang Tso-lin]] in Manchuria, and the growing Chinese Communist movement. | |||

Japan's position at the 1922 [[Washington Naval Conference]] was recognized although not to the extent that Japan nationalists would have liked (they saw any situation not at parity with Great Britain and the U.S. as an insult). | |||

Operating without knowledge of the high command but possibly with knowledge of th Palace, officers of the [[Kwangtung Army]] staged the September 1931 [[Manchurian Incident]] by which it claimed the right to exact military retribution against China and established the puppet state of [[Manchukuo]]. Subsequent incidents led the Japanese army to invade parts of Northern China. Japan also occupied for a time Shanghai, and following a protest by the [[League of Nations]], Japan withdrew from the League. | |||

Japan | ===Exploitation of China=== | ||

By the summer of 1937 Japan had seized Chinese territory to the outskirts of Beijing and began the [[Second Sino-Japanese War]]. Japan had established regional dominance over [[Manchuria]] and parts of [[Mongolia]], but still saw a need to expand to gain resources. Within government circles in the 1930s, alternative strategies included greater exploitation of China, [[Strike-North Faction|Strike-North]] into the Soviet Union and Siberia, and [[Strike-South Faction|Strike-South]] into [[Southeast Asia]] and Pacific islands. | |||

The [[Nine-Power Treaty]] was somewhat as a compromise; signatory nations agreed to abide by the [[Open Door Policy]] while the territorial integrity of China was to be respected. | |||

===China, French Indochina, and Strike South=== | |||

Following the German defeat of France in 1940, Japan saw opportunity to further squeeze China. It prevailed on the Vichy French government to allow Japan to occupy and use airbases in Northern [[French Indochina]] from which it could bomb China and interdict the flow of western aid to China through French Indochina. The U.S., in response, authorized a loan to China and passed the [[Export Control Act]] which authorized the president to restrict the export of strategic materials to nations he deemed threatened national security. Roosevelt used the act to embargo aviation fuel, scrap steel, and other materials to Japan. | |||

Once the Japanese had settled on the [[Strike-South Faction|Strike-South strategy]], they soon realized that they needed at least partial control of [[French Indochina]], both to cut off supplies moving north into China, and to provide air bases in range of targets further south and west. This led to complex relationships with [[Indochina and the Second World War|Indochina]], reflecting both the creation of [[Vichy France]], and the stronger German control of France through the [[Tripartite Pact]]. | |||

In September 1940, Japan entered the [[Tripartite Pact]] with Germany and Italy pledging to aid each other if attacked by another power. Vastly confusing this situation was, however, the April 1941 [[Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact]] pledging nonaggression between Germany and the Soviet Union. The inherent conflict between the two pacts, if the [[Strike-North Faction]] had not already been killed by poor Japanese performance against Soviet troops, made Strike-South the only expansionist strategy left. | |||

In | |||

Even in Strike-South, Japan preferred to limit its confrontations with the Western colonial powers. At first, it believed it might hold the conflict to Great Britain. | |||

===US-Japanese tensions=== | |||

Negotiations between the United States and Japan proved unproductive. [[U.S. Secretary of State]] Cordell Hull maintained an inflexible position that the first step in any resumption of trade between the U.S. and Japan would be a complete withdrawal of Japanese forces from French Indochina, a step that the militant nationalists controlling Japan were unwilling to take. Their other alternative was to seize the oil fields of the Dutch East Indies, an alternative for which they began war plans. In order to secure their lines of supply between Indonesia and Japan, they would need control of the British base at Singapore and the U.S. colony of the Philippines. Invasion of the Philippines, the Japanese correctly figured, would lead to war with the U.S., and given the strength of the U.S. navy in the Pacific as well as the productive capacity of the United States, the best hope for a Japanese victory in this war would be a decisive victory from which the U.S. would have little other alternatives than to negotiate a peace. To decisively defeat the U.S. fleet, would require a massive blow at a time when the U.S. Navy was least prepared and least expecting a Japanese attack: at the very beginning of the war. | |||

== The Pacific at war== | |||

In an effort to discourage Japan's war efforts in China, the United States, Britain, and the Dutch government in exile (still in control of the oil-rich [[Dutch East Indies]]) stopped selling oil and steel to Japan. This was the "ABCD encirclement" (American-British-Chinese-Dutch) designed to deny Japan of the raw materials needed to continue its war in China. Japan saw this as an act of aggression, as without these resources Japan's military machine would grind to a halt. On December 8, 1941, Japanese forces attacked the British colony of [[Hong Kong]], Shanghai, and the [[Philippines]], which was then a United States possession. Japan also used [[Vichy French]] bases in [[French Indochina]] to invade Thailand, then used the gained Thai territory to launch an assault against Malaya, a British colony, headed toward the great British naval base at Singapore. | |||

===Japanese strategy=== | |||

Japan had a grand strategy based both on establishing its regional dominance, and also to obtain economic resources it did not believe it could obtain by peaceful means. Within the military-dominated government, there had been a "Strike-South" and a "Strike-North" faction, respectively, seeing the needed resources in Southeast Asia or in Siberia. In either case, it had been conducting large-scale operations in Manchuria and China since 1931. | |||

Especially if Strike-South were taken, which would inevitably impact European allies of the United States, and quite possibly U.S. bases proper, the Japanese military strategy was to force the United States Fleet, after being attrited by peripheral attacks, to steam into the Western Pacific, where it would be vulnerable both to Japanese naval forces and land-based air forces. In support of this strategy, Japan had been building up a system of Pacific island bases since the 1920s. | |||

While Japan joined the [[Tripartite Pact]] in 1940, there had already been cooperation with Nazi Germany, and to a lesser extent with Italy. Japan also sought a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union. Prior joining the pact but with known German support, it moved into what was then [[French Indochina]] to support its war in China, asking then [[Vichy France]] for assistance. These moves were unacceptable within the [[Indochina and the Second World War|foreign policy of the United States regarding Southeast Asia]], and led to economic embargoes against Japan. | |||

ADM [[Isoroku Yamamoto]], Navy Vice Minister at the time planning intensified, knew the United States and North America well. He counseled against war with the United States, and said, that under the best circumstances, he estimated Japan could maintain a strategic offense for 6-18 months, probably 12, before U.S. industrial mobilization would overwhelm Japanese objectives. His recommendation was for a bold, short-term offensive followed by negotiations, rather than a decisive victory against the United States and other Western powers. Internal Japanese opposition to his views was sufficiently intense that he was transferred to the post of Commander-in-Chief, because be could better be protected against assassination aboard his flagship. Assassination was a very real threat inside Japanese military and government circles in the 1920s and 19302. | |||

It was not clear, to the Japanese, what they would do next after they conquered what they called the Southern Resource Area. Their military forces had always glorified the attack, and had little experience in consolidation, strategic defense, and logistics. | |||

===U.S. contingency strategy === | |||

The United States strongly supported China. There was little "isolationist" sentiment as American opinion, led by President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] was strongly hostile to Japan because of its efforts to conquer China. | |||

Army Chief of Staff [[George C. Marshall]] explained American strategy three weeks before Pearl Harbor:<ref> | |||

Robert L. Sherrod "Memorandum for David W. Hulburd, Jr." November 15, 1941. | |||

''The Papers of George Catlett Marshall, ed. Larry I. Bland et al. vol. 2, ''We Cannot Delay, July 1, 1939-December 6, 1941'' (1986), #2-602 pp. 676-681. Marshall made the statement to a secret press conference. </ref> | |||

:"We are preparing for an offensive war against Japan, whereas the Japs believe we are preparing only to defend the Philippines. ...We have 35 Flying Fortresses already there—the largest concentration anywhere in the world. Twenty more will be added next month, and 60 more in January....If war with the Japanese does come, we'll fight mercilessly. Flying fortresses will be dispatched immediately to set the paper cities of Japan on fire. There won't be any hesitation about bombing civilians—it will be all-out." | |||

The main U.S. contingency plan was called RAINBOW 5. U.S. counteroffensive strategy derived from the 1921 paper by Marine Major [[Earl Ellis]]. | |||

==Japanese | ===Initial Japanese attacks === | ||

Japan executed its [[Strike-South Faction|Strike-South]] plans with movements at [[Pearl Harbor]], the [[Malay Peninsula]] and [[Singapore]], and the [[Philippines]]. | |||

On December 7, the Japanese carrier-based [[Mobile Fleet]], led by Vice Admiral [[Chuichi Nagumo]] under the direction of [[Commander-in-Chief, Combined Fleet]] [[Isoroku Yamamoto]], launched a air attack on the American air bases and naval fleet in the [[Pearl Harbor (World War II)|attack on Pearl Harbor]], sinking or damaging the entire American battleship fleet. U.S. [[aircraft carrier]]s were not in the harbor, and the attack left [[submarine]]s and the logistical facilities undamaged. | |||

[[Image:USS West Virginia Pearl Harbor.jpg|thumb|250px|Survivors from the ''USS West Virginia'' being rescued. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor forced the United States into the war.]] | |||

Although Japan knew that it could not win a sustained and prolonged war against the United States, it was the Japanese hope that, faced with this sudden and massive defeat, the United States would agree to a negotiated settlement that would allow Japan to have free reign in China. This calculated gamble did not pay off; the United States refused to negotiate. Furthermore, the American losses were less serious than initially thought; the American carriers were out at sea while vital base facilities like the fuel oil storage tanks, whose destruction could have crippled the whole Pacific Fleet's operating capacity by itself, were left untouched. | |||

Until the Pearl Harbor, the United States had officially neutral, but in fact was the main supplier of money and munitions to Britain and China, and a major supplier to Soviet Union as wee. The aid went through the [[Lend-Lease]] program. Opposition to war in the United States vanished after the attack. On December 11, Nazi Germany declared war on the United States, drawing America into a two-theater war. In 1941, Japan had only a fraction of the manufacturing capacity of the United States, and was therefore perceived as a lesser threat than Germany. | |||

British, Indian and Dutch forces, already drained of personnel and matériel by two years of war with Germany, and heavily committed in the [[Middle East]], [[North Africa]] and elsewhere, were unable to provide much more than token resistance to the battle-hardened Japanese. The Allies suffered many disastrous defeats in the first six months of the war. Two major British warships, ''HMS Repulse'' and ''HMS Prince of Wales'' were sunk by a Japanese air attack off Malaya on December 10, 1941. The government of Thailand surrendered within 24 hours of Japanese invasion and formally allied itself with Japan. Thai military bases were used as a launchpad against Singapore and Malaya. [[Hong Kong]] fell on December 25 and U.S. bases on [[Guam]] and [[Wake Island]] were lost at around the same time. | |||

The Allied governments appointed the British General Sir [[Archibald Wavell]] as supreme commander of all "American-British-Dutch-Australian" (ABDA) forces in South East Asia. This gave Wavell nominal control of a huge but thinly-spread force covering an area from [[Burma]] to the [[Dutch East Indies]] and the [[Philippines]]. Other areas, including India, Australia and Hawaii remained under separate local commands. | |||

==Japanese strategy and offensives 1942== | |||

By early 1942, Japan was unsure what to do next. Their first concern was consolidating their gains in Southeast Asia, which provided adequate resources. They needed, however, more military buffer for their security; Australia was a potential Allied base for counterattacks.<ref>{{citation | |||

| url = http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&cd=11&ved=0CBEQFjAAOAo&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.aph.gov.au%2Flibrary%2Fpubs%2Fbp%2F1992%2F92bp06.pdf&ei=6zh8TPT0CcH38Ab7uPTFBg&usg=AFQjCNFajFhagoAIeyNZ554aBnRy1Eh1hQ | |||

}}</ref> | |||

*West into India | |||

*South into Australia | |||

*East towards Midway, Polynesia and Hawaii | |||

1942 began with the Allies in rout, but several major actions showed the turning of the tide. The [[Battle of the Coral Sea]] was the first engagement in which a Japanese force turned back from an invasion. The [[Doolittle Raid]] made the Japanese believe their eastern perimeter did not extend far enough, and, of a variety of options, selected the invasion of Midway. | |||

=== | ===Early Japanese attacks=== | ||

January, 1942 saw the invasions of Burma, the [[Dutch East Indies]], [[New Guinea]], the [[Solomon Islands]] and the capture of Manila, [[Kuala Lumpur]] and [[Rabaul, battle of|Rabaul]]. After being driven out of Malaya, Allied forces were trapped in the Singapore and, approximately 130,000 surrendered to the Japanese on February 15, 1942<ref>[http://www.awm.gov.au/atwar/remembering1942/singapore/transcript.htm]</ref> Indian, Australian and British troops along with Dutch sailors, became prisoners of war. The pace of conquest was rapid: [[Bali]] and [[Timor]] also fell in February. The rapid collapse of Allied resistance had left the "ABDA area" split in two. | |||

At the [[Battle of the Java Sea]], in late February and early March, the Japanese Navy inflicted a resounding defeat on the main ABDA naval force, under Admiral Karel Doorman. The Netherlands East Indies campaign subsequently ended with the surrender of Allied forces on Java. | |||

The British, under intense pressure, made a fighting retreat from Rangoon to the Indo-Burmese border. This cut the [[Burma Road]] which was the western Allies' supply line to the Chinese National army commanded by [[Chiang Kai-shek]]. Cooperation between the Chinese Nationalists and the Communists had waned from its zenith at [[Battle of Wuhan]], and the relationship between the two had gone sour as both attempted to expand their area of operations in occupied territories. Most of the Nationalist guerrilla areas were eventually overtaken by the Communists. On the other hand, some Nationalist units, along with collaborationists, were deployed for blockading the Communists rather than against the Japanese. Further, many of the forces of the Chinese Nationalists were warlords allied to Chiang Kai-shek, but not directly under his command. "Of the 1,200,000 troops under Chiang's control, only 650,000 were directly controlled by his generals, and another 550,000 controlled by warlords who claimed loyalty to his government; the strongest force was the Szechuan army of 320,000 men. The defeat of this army would do much to end Chiang's power."<ref> Edwin P. Hoyt, ''Japan's War'' (1986) pp. 262-263.</ref> The Japanese used these [[division (military)|divisions]] to press ahead in their offenses. | |||

Filipino and U.S. forces put up a fierce conventional in the Philippines until May 8, 1942; in all than 80,000 men surrendered, but an active [[resistance movement in the Philippines]] formed. | |||

Meanwhile, Japanese aircraft had all but eliminated Allied air power in South-East Asia and were making attacks on Darwin in northern Australia, beginning with a disproportionately large and psychologically devastating raid on Darwin, February 19. | |||

===Battle of Ceylon=== | |||

A raid by a powerful Japanese Navy aircraft carrier force into the Indian Ocean resulted in the [[Battle of Ceylon]] and sinking of the only British carrier, ''HMS Hermes'' in the theater, as well as 2 cruisers and other ships. This effectively drove British naval forces from the Indian ocean and paving the way for Japanese conquest of Burma and a drive towards India. | |||

=== | ===First Japanese reverse: Coral Sea=== | ||

{{main|Battle of the Coral Sea}} | |||

By mid-1942, the [[Japanese Combined Fleet]] found itself holding a vast area, even though it lacked the aircraft carriers, aircraft, and aircrew to defend it, and the freighters, tankers, and destroyers necessary to sustain it. Moreover, Fleet doctrine was incompetent to execute the proposed "barrier" defense.<ref>Parillo, ''Japanese Merchant Marine''; Peattie & Evans, '''Kaigun'''.</ref> Instead, they decided on additional attacks in both the south and central Pacific. While Yamamoto had used the element of surprise at Pearl Harbor, Allied codebreakers now turned the tables. They discovered an attack against [[Port Moresby]], New Guinea was imminent. | |||

If Port Moresby fell, it would give Japan control of the seas to the immediate north of Australia. Nimitz rushed the carrier ''[[USS Lexington (CV-2)]]'', under Admiral [[Frank Fletcher]], to join ''[[USS Yorktown (CV-5)]]'' and a U.S.-Australian task force, with orders to contest the Japanese advance. The resulting [[Battle of the Coral Sea]] was the first naval battle in which ships involved never sighted each other and aircraft were solely used to attack opposing forces. | |||

===Reorganization=== | |||

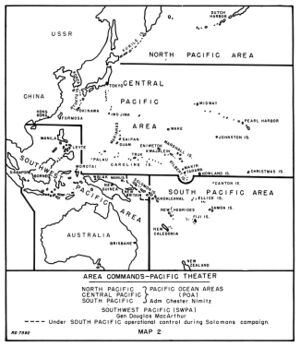

[[Image:Ww2-pacific-theater.jpg|thumb|Map of the theater of operations in the Pacific Ocean and East Asia during the [[Second World War]]. Charles W. Boggs Jr., ''[http://ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/USMC-M-AvPhil/USMC-M-AvPhil-1.html Marine Aviation in Philippines]'' (Washington: Historical Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1951), 2. ]] | |||

After ABDA became defunct, the Americans set up four commands, the [[Southwest Pacific Area]], under General [[Douglas MacArthur]] in Australia, and three Pacific areas (North, Central and South), all under Admiral [[Chester W. Nimitz]] at Pearl Harbor. The China-Burma-India (CBI) theater was a separate command, involving the British and Chinese, as well as Americans. | |||

In early 1942, the governments of smaller powers began to push for an inter-governmental Asia-Pacific war council, based in Washington. The Pacific War Council was set up in Washington on April 1, 1942, but it never had any direct operational control and any recommendations it made were referred to the U.S.-British [[Combined Chiefs of Staff]], which was also in Washington. | |||

Allied resistance, at first symbolic, gradually began to stiffen. Australian and Dutch forces led civilians in a prolonged guerrilla campaign in Portuguese Timor. | |||

===Striking East=== | |||

{{main|Battle of Midway}} | |||

The [[Doolittle Raid]] did minimal damage, but was a huge morale booster for the Allies. Only after the war was its immense strategic impact realized. Not only did the Japanese transfer air defense resources, needed in the field, back to the home islands, they concluded that their defense perimeter needed to extend further east. To extend it, they concluded they needed to seize [[Midway Island]]. They overextended themselves to fight the [[Battle of Midway]], a major Japanese defeat that was, arguably, the turning point of the Pacific War. | |||

Yamamoto's primary goal was the seizure of the airfield on [[Midway]]; a secondary goal was to destroy U.S. fleet resources. Midway was a decisive victory for the U.S. Navy and the end of Japanese offensive aspirations in the Pacific. It cost the Japanese four fleet carriers, but, even more important, superbly trained pilots. One of Japan's great mistakes was not developing a continuous pipeline to train new pilots, and share the expertise of experienced pilots while giving them needed rest and preparing them for higher levels of command and staff. | |||

==Counteroffensive: New Guinea and the Solomons == | |||

Japanese land forces continued to advance in the [[Solomon Islands]] and [[New Guinea]]. From July, 1942, a few Australian militia battalions, many of them very young and untrained, fought a stubborn rearguard action in [[New Guinea]], against a Japanese advance along the Kokoda Track, towards [[Port Moresby]], over the rugged Owen Stanley Ranges. The Militia, worn out and severely depleted by casualties, were relieved in late August by regular troops from the Second Australian Imperial Force, returning from action in the Middle East. | |||

== | In early September 1942, Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces ("Japanese marines") attacked a strategic Australian Air Force base at Milne Bay, near the eastern tip of New Guinea. They were beaten back by the [[Australian Army]] and some U.S. forces, inflicting the first outright defeat on Japanese land forces since 1939. | ||

===Guadalcanal=== | |||

{{main|Guadalcanal campaign}} | |||

At the same time as major battles raged in New Guinea, Allied forces spotted a Japanese airfield under construction at Guadalcanal. The Allies made an amphibious landing in August to convert it to their use and start to reverse the tide of Japanese conquests. As a result, Japanese and Allied forces both occupied various parts of [[Guadalcanal campaign|Guadalcanal]]. Over the following six months, both sides fed resources into an escalating battle of attrition on the island, at sea, and in the sky, with eventual victory going to the Allies in February 1943. | |||

The [[Battle of Midway]] cost the Japanese a critical number of aircraft carriers and pilots. The [[Guadalcanal campaign]], however, signaled the shift of the Allies to systematic offense.<ref name=Potter-Halsey>{{citation | |||

| author = E. B. Potter | |||

| publisher = U.S. Naval Institute | year = 1985 | |||

| isbn = 0870211463 | |||

| title = Bull Halsey}}, p. 179</ref> | |||

It was a campaign the Japanese could ill afford. A majority of Japanese aircraft from the entire South Pacific area was drained into the Japanese defense of Guadalcanal. Japanese logistics, as happened time and again, failed; only 20% of the supplies dispatched from Rabaul to Guadalcanal ever reached there. As a result the 30,000 Japanese troops on Guadalcanal lacked heavy equipment, adequate ammunition and even enough food, and were subjected to continuous harassment from the air. 10,000 were killed, 10,000 starved to death, and the remaining 10,000 were evacuated in February 1943, in a greatly weakened condition. | |||

The U.S. Air Forces based at Henderson Field became known as the Cactus Air Force (from the codename for the island), and held their own. The Japanese launched a pair of ill-coordinated attacks on U.S. positions around Henderson Field to suffer bloody repulse and then to suffer even worse losses to starvation and disease during the retreat. | |||

===New Guinea and the Solomons=== | |||

By late 1942, the Japanese were also retreating along the Kokoda Track in the highlands of New Guinea. Australian and U.S. counteroffensives culminated in the capture of the key Japanese beachhead in eastern New Guinea, the Buna-Gona area, in early 1943. | |||

In June 1943, the Allies launched [[Operation CARTWHEEL]], aimed at isolating the major Japanese forward base, at Rabaul, and cutting its supply and communication lines without actually invading it. This prepared the way for [[Chester Nimitz|Nimitz]]'s island-hopping campaign towards Japan. | |||

==Allied offensives, 1943-44== | ==Allied offensives, 1943-44== | ||

[[Alfred Thayer Mahan|Mahanian]] doctrine called for a decisive naval battle. The Japanese repeatedly sought such a battle, but the U.S. did not. Instead it pushed closer and closer to the Japanese home islands. The Allied advance could only be stopped by a Japanese naval attack, which became increasingly difficult as Japan ran low on fuel, modern planes, trained pilots and major warships. | |||

Not every Japanese stronghold had to be captured; some, like Truk, Rabaul and Formosa were neutralized by air attack and bypassed. The goal was to get close to Japan itself, then launch massive strategic air attacks, improve the submarine blockade, and finally (if necessary) execute an invasion. The technique of amphibious landings to seize forward bases in preparation for a great fleet battle was propounded in 1921 by U.S. Marine MAJ [[Earl Ellis]]. | |||

Midway proved to be the last great naval battle for two years. Admiral King complained that the Pacific deserved 30% of Allied resources but was getting only 15%; he used what he had to neutralize the Japanese forward bases at [[Rabaul, battle of|Rabaul]] and [[Truk]]. | |||

The United States used the two years to turn its vast industrial potential into actual ships, planes, and trained aircrew. At the same time, Japan, lacking an adequate industrial base or technological strategy, and lacking a good aircrew training program, fell further and further behind. | |||

On 18 October 1943, land-based aircraft bombed [[Rabaul, battle of|Rabaul]] <ref name=Cleaver>{{citation | |||

| title = Raid on Rabaul: B-25 gunships terrorize Japanese shipping | |||

| author = Cleaver, Thomas McKelvey | |||

| journal = Flight Journal | |||

| date = August 2004 | |||

| url = http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3897/is_200408/ai_n9458149/print}}</ref> This was followed, on 5 November, by a carrier raid that rendered Rabaul ineffective. <ref name=>{{citation | |||

| url = http://www.combinedfleet.com/btl_rab.htm | |||

| title = Carrier Raid on Rabaul (November 5, 1943) | |||

}}</ref> Still, the U.S. continued to harass Rabaul by air, and with a destroyer raid, into 1944. | |||

===[[Operation GALVANIC]] (Gilberts)=== | |||

<blockquote>This force will seize, occupy, and develop Makin, Tarawa, and Abemama, and will vigorously deny Nauru to the enemy, in order to gain control of the Gilbert Islands and to prepare for operations against the Marshalls. <ref>{{citation | |||

| url = http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/BBBO/BBBO-9.html | |||

| contribution = Chapter IX: Operation GALVANIC (the Gilbert Islands) | |||

| title = Beans, Bullets and Black Oil | |||

| author = Worrall Reed Carter | |||

| publisher = U.S. Navy}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

=== | The major combat operations, therefore, would be the [[Battle of Makin]], [[Battle of Tarawa]], the [[Battle of Abemana]], and [[Raids against Nauru]]. | ||

====Battle of Tarawa==== | |||

{{main|Battle of Tarawa}} | |||

In November 1943, Marines sustained high casualties when they overwhelmed the 4,500-strong Japanese garrison on the island of Betio in the Tarawa atoll. This helped the allies to improve the techniques of [[amphibious warfare]], learning from their mistakes and implementing changes such as thorough pre-emptive bombings and bombardment, more careful planning regarding tides and landing craft schedules, and better overall coordination. | |||

===[[Operation Flintlock]] (Marshalls)=== | |||

===Intercepting Yamamoto=== | |||

On April 13, 1943, American [[communications intelligence]] intercepted messages, in a relatively low-level cryptosystem, giving the inspection itinerary of Admiral [[Isoroku Yamamoto]], commanding the Japanese Combined Fleet. There were points along his inspection tour where long-range fighters could intercept and shoot down his aircraft. <ref name=Layton>{{citation | |||

| title = "And I was There": Pearl Harbor and Midway: Breaking the Secrets | |||

| author =Edwin T. Layton, Roger Pineau and John Costello | |||

| publisher = William Morrow & Company | year = 1985 | isbn-0688948838 | |||

}}, pp. 474-479</ref> | |||

The decision to intercept his aircraft and kill him required Joint Chiefs and Presidential approval, first because it could suggest to the Japanese that their communications had been broken, and other reasons such as the precedent of using assassination. Pacific Fleet intelligence officer Layton, and possibly others in the decisionmaking, had the added burden of having known and admired Yamamoto the man. | |||

On April 18, Yamamoto died when a force of 18 U.S. Army Air Force [[P-38 Lightning]] fighters intercepted and shot down the two bombers carrying staff officers, which were escorted by six Japanese fighters. | |||

{{quotation|There was only one Yamamoto, and no one is able to replace him His loss is an unsupportable blow to us|Adm. Mineichi Koga, Yamamoto's successor}}. | |||

===Recapture of the Aleutians=== | |||

On 11 May, U.S. Army forces landed on the Japanese-held island of Attu, in the Alaskan Aleutian chain. It was secured after two weeks of hard fighting. An extensive bombardment preceded the 15 August invasion of nearby Kiska, but the Japanese had evacuated Kiska without the U.S. becoming aware of it. <ref>Layton, pp. 476-477</ref> | |||

===The submarine war=== | |||

{{main|World War II, submarine operations}} | |||

U.S. [[submarine]]s (with some aid from the British and Dutch), operating from bases in Australia, Hawaii, and Ceylon, played a major role in defeating Japan. Japanese submarines, however, played a minimal role, although they had the best torpedoes of any nation in the Second World War, and quite good submarines. The difference in results is due to the very different doctrines of the sides, which, on the Japanese side, were based on cultural traditions. | |||

==The beginning of the end in the Pacific, 1944== | |||

U.S. strategy for the war in the Pacific derived from [[Joint Chiefs of Staff]] (JCS) decisions at the [[Cairo Conference (1943)]] to obtain "bases from which the unconditional surrender of Japan can be forced."<ref name=Morison>{{citation | |||

| title = History of United States Naval Operations in World War II | |||

| author = Samuel Eliot Morison | |||

| volume = Volume XII: Leyte, June 1944-January 1945 | |||

| publisher = Atlantic Monthly/Little, Brown | |||

| year = 1970 | |||

}}, p. 4</ref> There was, however, little clarity and much argument among the Joint Chiefs and the two theater commanders, [[Douglas MacArthur]] for the [[Southwest Pacific Area]] and [[Chester Nimitz]] for the [[Pacific Ocean Areas]]. JCS guidance to Nimitz and MacArthur, dated March 12, 1944, stated "The JCS have decided that the most feasible approach to Formosa, Luzon and China is by way of the Marianas, the Carolines, Palau, and Mindonoro." | |||

The | The great distance of Formosa and Luzon from Japan made these objectives unusable as bases for attacks on the Japanese home islands. Bases in China may have supported ultra-long range bombers, but events soon marginalized this option as well. In May 1944, the Japanese Army, moved into Eastern China. After this, the JCS suggested bypassing all the intermediate bases (such as Luzon and Formosa) and directly attacking [[Kyushu]].<ref>Morison, 5-7.</ref> This suggestion outraged MacArthur, whose personal agenda required the liberation of the Philippines above all else, but it reflected the desire of Army Chief of Staff [[George C. Marshall]] to avoid unnecessary land campaigns. MacArthur was told that that personal and political considerations should not override the goal of defeating Japan.<ref>Courtney Whitney, ''MacArthur, His Rendevous with History'' (1966), quoted in Morison, 7.</ref> | ||

MacArthur had a deep emotional bond to the Philippines. MacArthur's personal ambition since leaving the Philippines in 1942 was to return.<ref name=Mac-7>"The Philippine Islands constituted the main objective of General MacArthur's planning from the time of his departure from Corregidor in March 1942 until his dramatic return to Leyte two and one half years later," {{citation | |||

| url = http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/macarthur%20reports/macarthur%20v1/ch07.htm | |||

| chapter = CHAPTER VII--THE PHILIPPINES: STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE | |||

| title = Reports of General MacArthur | |||

| publisher = Office of the Chief of Military History, [[U.S. Army]] | |||

| year = 1966 | |||

}}</ref> He believed that the honor of the United States required the liberation of the islands and that such an objective was strategically sound. He saw Leyte as the base from which the rest of the Philippines could be taken. <ref name=Mac-Ch8>{{citation | |||

| title=Reports of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific | |||

| chapter = Chapter VIII, The Leyte Operation | |||

| url = http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/macarthur%20reports/macarthur%20v1/ch08.htm | |||

| publisher = Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army | year = 1966}}</ref> | |||

MacArthur and his staff responded to Marshall's suggestion on June 15, 1944, with the Reno V plan. This plan called for an October invasion of [[Mindanao]] to cover a November invasion of Leyte and further movements on a line [[Luzon]]-[[Bicol Peninsula]]-[[Mindonoro]]-[[Lingayen Gulf]]-[[Manila]]. As a bold, risky, and expensive plan, it had lots of detractors; Admiral King, and even MacArthur's air commander, General Kinney, criticized it. | |||

Eventually, President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] intervened to break the deadlock between King and Nimitz versus MacArthur. Roosevelt traveled to Honolulu, accompanied by his chief of staff, Admiral Leahy, and met with MacArthur in July.<ref>Morison, 8-11</ref> | |||

===Saipan === | |||

===Saipan | {{main|Battle of Saipan}} | ||

{{main|Battle of Saipan | |||

On June 15, 1944, 535 ships began landing 128,000 U.S. Army and Marine personnel on on the island of [[Saipan]]. The Allied objective was the creation of airfields — within [[B-29]] range of Tokyo. The ability to plan and execute such a complex operation in the space of 90 days was indicative of Allied logistical superiority. | On June 15, 1944, 535 ships began landing 128,000 U.S. Army and Marine personnel on on the island of [[Saipan]]. The Allied objective was the creation of airfields — within [[B-29]] range of Tokyo. The ability to plan and execute such a complex operation in the space of 90 days was indicative of Allied logistical superiority. | ||

It was imperative for Japanese commanders to hold Saipan | It was imperative for Japanese commanders to hold Saipan, as inside Japan, Saipan was regarded as part of the innermost defense perimeter, and its capture would strengthen the peace faction, unknown outside Japan. To help the land battle, the Japanese sent the Mobile Fleet, under Admiral [[Jisaburo Ozawa]], to attack the Fifth Fleet in what became known as the [[Battle of the Philippine Sea]], or, informally, the "Marianas Turkey Shoot". | ||

Admiral [[Raymond | When it fell, so did the government of [[Hideki Tojo]], who was replaced as Prime Minister by [[Prince Konoye]]. The new cabinet was more inclined toward peace, but certainly not to immediate capitulation; Army elements still insisted on total war. | ||

===Battle of the Philippine Sea=== | |||

{{main|Philippine Sea, battle of|Battle of the Philippine Sea}} | |||

The only way to do this was to destroy the [[Fifth United States Fleet]], which had 15 big carriers and 956 planes, 28 battleships and cruisers, and 69 destroyers. Vice Admiral [[Jisaburo Ozawa]] attacked with nine-tenths of Japan's fighting fleet, which included nine carriers with 473 planes, 18 battleships and cruisers, and 28 destroyers. Ozawa's pilots were outnumbered 2-1 and their aircraft were becoming obsolete. The Japanese had substantial [[anti-aircraft artillery]], but lacked [[proximity fuze]]s and good [[radar]]. With the odds stacked against him, Ozawa devised an appropriate strategy. His planes had greater range because they were not weighed down with protective armor; they could attack at about 480 km (300 mi), and could search a radius of 900 km (560 mi). U.S. Navy [[F6F Hellcat]] fighters could only attack within 200 miles, and only search within a 325 mile radius. Ozawa planned to use this advantage by positioning his fleet 300 miles out. The Japanese planes would hit the U.S. carriers, land at Guam to refuel, then hit the enemy again, when returning to their carriers. Ozawa also counted on about 500 ground-based planes at [[Guam]] and other islands. | |||

Admiral [[Raymond Spruance]] was in overall command of the 5th Fleet. The Japanese plan would have failed if the much larger U.S. fleet had closed on Ozawa and attacked aggressively; Ozawa had the correct insight that the unaggressive Spruance would not attack. U.S. Admiral [[Marc Mitscher]], in tactical command of Task Force 58, with its 15 carriers, was aggressive but Spruance vetoed Mitscher's plan to hunt down Ozawa because Spruance's decisions made his first priority protection of the Saipan landing. | |||

The forces converged in the largest sea battle of World War II up to that point. Over the previous month American destroyers had destroyed 17 of the 25 submarines Ozawa had sent ahead. Repeated U.S. raids destroyed the Japanese land-based planes. Ozawa's main attack lacked coordination, with the Japanese planes arriving at their targets in a staggered sequence. Following a directive from Nimitz, the U.S. carriers all had combat information centers, which interpreted the flow of radar data instantaneously and radioed interception orders to the Hellcats. The result was later dubbed the ''Great Marianas Turkey Shoot''. The few attackers to reach the U.S. fleet encountered massive AA fire with proximity fuzes. Only one American warship was slightly damaged. | The forces converged in the largest sea battle of World War II up to that point. Over the previous month American destroyers had destroyed 17 of the 25 submarines Ozawa had sent ahead. Repeated U.S. raids destroyed the Japanese land-based planes. Ozawa's main attack lacked coordination, with the Japanese planes arriving at their targets in a staggered sequence. Following a directive from Nimitz, the U.S. carriers all had combat information centers, which interpreted the flow of radar data instantaneously and radioed interception orders to the Hellcats. The result was later dubbed the ''Great Marianas Turkey Shoot''. The few attackers to reach the U.S. fleet encountered massive AA fire with proximity fuzes. Only one American warship was slightly damaged. | ||

| Line 140: | Line 223: | ||

On the second day U.S. reconnaissance planes finally located Ozawa's fleet, 275 miles away and submarines sank two Japanese carriers. Mitscher launched 230 torpedo planes and dive bombers. He then discovered that the enemy was actually another 60 miles further off, out of aircraft range. Mitscher decided that this chance to destroy the Japanese fleet was worth the risk of aircraft losses. Overall, the U.S. lost 130 planes and 76 aircrew. However, Japan lost 450 planes, three carriers and 445 pilots. The Imperial Japanese Navy's carrier force was effectively destroyed. | On the second day U.S. reconnaissance planes finally located Ozawa's fleet, 275 miles away and submarines sank two Japanese carriers. Mitscher launched 230 torpedo planes and dive bombers. He then discovered that the enemy was actually another 60 miles further off, out of aircraft range. Mitscher decided that this chance to destroy the Japanese fleet was worth the risk of aircraft losses. Overall, the U.S. lost 130 planes and 76 aircrew. However, Japan lost 450 planes, three carriers and 445 pilots. The Imperial Japanese Navy's carrier force was effectively destroyed. | ||

=== | ===Philippines counteroffensive=== | ||

{{main|Philippines counteroffensive}} | |||

[{Douglas MacArthur]] was deeply committed to ousting the Japanese from the Philippines. He had had opposition on the [[Joint Chiefs of Staff]] to a strategy making them a priority, but a combination of factors changed that. | |||

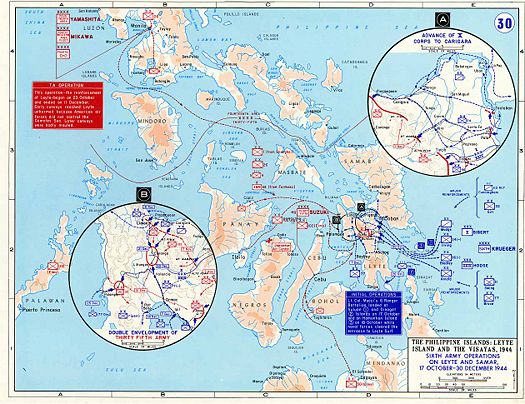

[[Image:Leyte-1944.jpg|thumb|right|525px|American reconquest of Philippines, 1944-45]] | |||

Third and Fifth Fleet staff agreed on three naval objectives in support of land operations:<ref>Morison, 57.</ref> | |||

*Air strikes by Third Fleet and long-range land-based aircraft on Okinawa, Formosa, and Northern Leyte on October 10-13. | |||

*Attacks by the Seventh Fleet on Bicol Peninsula, Leyte, Cebu and Negros, and direct supports of the actual landings, October 16-20. | |||

*"Strategic support" (which wasn't clearly defined) by the Third Fleet from October 21 onwards. | |||

On the Allied side, the main battle fleet, under Admiral [[Chester W. Nimitz]], Commander of the Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas. alternated between two commanders and staffs; one would carry out an operation while the other would plan the next. It was designated Third Fleet while under Vice Admiral [[William Halsey]] and Fifth Fleet while under Vice Admiral [[Raymond Spruance]]. This was not the key American command problem, which was more at the level of conflict between Nimitz and Southwest Pacific Area commander [[Douglas MacArthur]]. Under MacArthur was the Seventh Fleet, principally an amphibious rather than a sea battle force. Air command was also divided, with the heaviest bombers directly under the command of Washington. | |||

Both Halsey and Spruance were strong commanders with very different styles. Halsey himself speculated that the outcome, for the Allies, might have been better if he, rather than Spruance, had commanded at the Philippine Sea, while Spruance had taken his place at Leyte Gulf. War is filled with might-have-beens. | |||

====Preparatory operations==== | |||

On 9-10 September, Third Fleet units, supporting impending landings on Morotai and Palau, made air strikes on Mindonoro, and discovered significant weaknesses in Japanese air defense. It was determined that Southwest Pacific land-based bombers, operating out of New Guinea fields, had caused severe damage to enemy air installations on the island. Exploiting the weakness, the Third Fleet raided the [[Visayas]] on 12-13 September, causing substantial damage to aircraft and airfields. <ref>Macarthur Reports, Chapter 7, pp. 172-173</ref> | |||

MacArthur chose to occupy Morotai Island, off Halmahera, as an intermediate base, with landings starting on 15 September by the U.S. Army 31st Division and 126th Regimental Combat Team of the 32nd Division plus supporting combat and service troops, directed by XI Corps. Simultaneously, the 1st Division, [[United States Marine Corps|U.S. Marine Corps]], followed by the Army's 81st Division, took Palau and Angaur in the Palau group. Ulithi was taken on the 23rd.<ref>Macarthur Reports, Chapter 7, pp. 175-178</ref> | |||

Morotai and Palau, 350-500 miles from Leyte, became the main bases for Army fighters, still distant for WWII aircraft. Ulithi became the main staging harbor. | |||

Two-pronged drives to capture Japanese-held islands, building a ever-closer set of airfields for attacks on the Japanese home islands. In two key cases, an initial American landing was followed by a sea battle against supporting and reinforcing forces. While the Allies won the sea battles, both were troubled by problems of divided command. | |||

====Initial landings==== | |||

[[Image:Douglas MacArthur lands Leyte.jpg|thumb|350px|left|General [[Douglas MacArthur]] wades ashore during the landings at Leyte, the Philippines]] | |||

On 20 October 1944, the [[Sixth United States Army]], under Gen. [[Walter Krueger]], supported by naval and air bombardment, landed on the favorable eastern shore of [[Leyte]], one of the three large Philippine Islands, north of [[Mindanao]]. [[United States Seventh Fleet]], under [[Thomas Kinkaid]], conducted the amphibious operations and remained in support. | |||

====Leyte Gulf 1944==== | |||

{{main|Battle of Leyte Gulf}} | |||

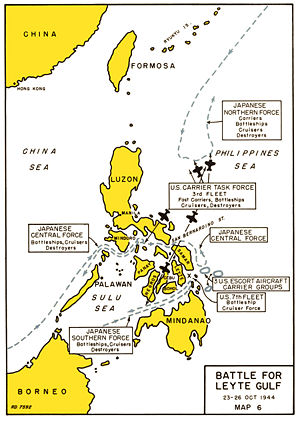

[[Image:Leyte-map1.jpg|thumb|300px|right]] | |||

The Battle of Leyte Gulf, October 23-26, 1944, was the largest naval battle in history. It involved coordinated Japanese attacks designed to hit the hundreds of thousands of American soldiers who had just landed at Leyte Gulf, and their supply ships. Severe communications failures on both sides characterized the battle, which ended in a total American victory and the end of Japanese sea power. | |||

Japan was heavily outgunned, so it designed a trick that would neutralize American strength. ''Sho-1'' called for using the remaining Japanese carriers as a decoy, knowing they would all be destroyed, to pull the main American battle fleet, the Third Fleet, north away from the real action. Then two other Japanese fleets would attack Leyte from the center and the south.<ref> For the relative strengths of the fleets see Vincent P. O'Hara, ''The U.S. Navy Against the Axis: Surface Combat, 1941-1945'' (2007) pp 261-2</ref> The plan almost worked, but the Japanese had poor radios and the different units were not in touch; the Japanese Army knew what was happening but it never talked to the Navy and did not help out. | |||

====Land invasion expands==== | |||

The U.S. Sixth Army continued its advance from the east, as the Japanese rushed reinforcements to the [[Ormoc Bay]] area on the western side of the island. While the Sixth Army was reinforced successfully, the U.S. Fifth Air Force was able to devastate the Japanese attempts to resupply. In torrential rains and over difficult terrain, the advance continued across Leyte and the neighboring island of Samar to the north. On 7 December 1944, U.S. Army units landed at Ormoc Bay and, after a major land and air battle, cut off the Japanese ability to reinforce and supply Leyte. Although fierce fighting continued on Leyte for months, the U.S. Army was in control. | |||

On | On 15 December 1944, landings against minimal resistance were made on the southern beaches of the island of [[Mindoro]], a key location in the planned [[Lingayen Gulf]] operations, in support of major landings scheduled on [[Luzon]]. On 9 January 1945, on the south shore of Lingayen Gulf on the western coast of Luzon, General Krueger's Sixth Army landed his first units. Almost 175,000 men followed across the twenty-mile beachhead within a few days. With heavy air support, Army units pushed inland, taking Clark Field, 40 miles northwest of [[Manila]], in the last week of January. | ||

Two more major landings followed, one to cut off the [[Bataan Peninsula]], and another, that included a parachute drop, south of Manila. Pincers closed on the city and, on | Two more major landings followed, one to cut off the [[Bataan Peninsula]], and another, that included a parachute drop, south of Manila. Pincers closed on the city and, on 3 February 1945, elements of the 1st Cavalry Division pushed into the northern outskirts of Manila and the 8th Cavalry passed through the northern suburbs and into the city itself. | ||

As the advance on Manila continued from the north and the south, the Bataan Peninsula was rapidly secured. On | As the advance on Manila continued from the north and the south, the Bataan Peninsula was rapidly secured. On 16 February, paratroopers and amphibious units assaulted [[Corregidor]], and resistance ended there on 27 February. | ||

In all, ten U.S. divisions and five independent regiments battled on Luzon, making it the largest campaign of the Pacific war, involving more troops than the United States had used in North Africa, Italy, or southern France. | In all, ten U.S. divisions and five independent regiments battled on Luzon, making it the largest campaign of the Pacific war, involving more troops than the United States had used in North Africa, Italy, or southern France. | ||

[[Palawan Island]], between [[Borneo]] and Mindoro, the fifth largest and western-most Philippine Island, was invaded on | [[Palawan Island]], between [[Borneo]] and Mindoro, the fifth largest and western-most Philippine Island, was invaded on 28 February, with landings of the Eighth Army at Puerto Princesa. The Japanese put up little direct defense of Palawan, but cleaning up pockets of Japanese resistance lasted until late April, as the Japanese used their common tactic of withdrawing into the mountain jungles, disbursed as small units. Throughout the Philippines, U.S. forces were aided by Filipino guerrillas to find and dispatch the holdouts. | ||

The U.S. Eighth Army then moved on to its first landing on Mindanao ( | The U.S. Eighth Army then moved on to its first landing on Mindanao (17 April), the last of the major Philippine Islands to be taken. Mindanao was followed by invasion and occupation of Panay, Cebu, Negros and several islands in the Sulu Archipelago. These islands provided bases for the U.S. Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces to attack targets throughout the Philippines and the [[South China Sea]]. | ||

==The final stages of the war== | ==The final stages of the war== | ||

=== | ===China-Burma-India=== | ||

===Southwest Pacific=== | |||

The Borneo Campaign of 1945 was the last major Allied campaign in the South West Pacific Area. In a series of amphibious assaults between May 1 and July 21, the Australian I Corps, under General Leslie Morshead, attacked Japanese forces occupying the island. Allied naval and air forces, centred on the [[U.S. 7th Fleet]] under Admiral [[Thomas Kinkaid]], the Australian First Tactical Air Force and the U.S. Thirteenth Air Force also played important roles in the campaign. | |||

=== | |||

The Borneo Campaign of 1945 was the last major Allied campaign in the South West Pacific Area. In a series of amphibious assaults between May 1 and July 21, the Australian I Corps, under General Leslie Morshead, attacked Japanese forces occupying the island. Allied naval and air forces, centred on the [[U.S. 7th Fleet]] under Admiral [[Thomas Kinkaid]], the | |||

The campaign opened with a landing on the small island of Tarakan on May 1. This was followed on June 1 by simultaneous assaults in the north west, on the island of Labuan and the coast of [[Brunei]]. A week later the Australians attacked Japanese positions in North Borneo. The attention of the Allies then switched back to the central east coast, with the last major amphibious assault of World War II, at Balikpapan on July 1. | The campaign opened with a landing on the small island of Tarakan on May 1. This was followed on June 1 by simultaneous assaults in the north west, on the island of Labuan and the coast of [[Brunei]]. A week later the Australians attacked Japanese positions in North Borneo. The attention of the Allies then switched back to the central east coast, with the last major amphibious assault of World War II, at Balikpapan on July 1. | ||

Although the campaign was criticised in Australia at the time, and in subsequent years, as pointless or a "waste" of the lives of soldiers, it did achieve a number of objectives, such as increasing the isolation of significant Japanese forces occupying the main part of the [[Dutch East Indies]], capturing major oil supplies and freeing Allied prisoners of war, who were being held in deteriorating conditions. | Although the campaign was criticised in Australia at the time, and in subsequent years, as pointless or a "waste" of the lives of soldiers, it did achieve a number of objectives, such as increasing the isolation of significant Japanese forces occupying the main part of the [[Dutch East Indies]], capturing major oil supplies and freeing Allied prisoners of war, who were being held in deteriorating conditions. | ||

===Pacific Ocean=== | |||

{{seealso|Battle of Iwo Jima}} | |||

{{seealso|Battle of Okinawa}} | |||

=== | ===Attacks on Japan=== | ||

=== | |||

Hard-fought battles on the Iwo Jima and Okinawa resulted in horrific casualties on both sides, but finally produced a Japanese retreat. Faced with the loss of most of their experienced pilots, the Japanese increased their use of [[Kamikaze]] tactics in an attempt to create unacceptably high casualties for the Allies, who were now joined by the British fleet. Upwards of a third of the U.S. fleet was hit, and the U.S. Navy recommended against an invasion of Japan in 1945. It proposed to force a Japanese surrender through a total naval blockade and air raids. | |||

====Strategic bombing==== | |||

Towards the end of the war as the [[World War II, air war|role of strategic bombing]] became more important, a new command for the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific was created to oversee all U.S. strategic bombing in the hemisphere, under Air Force General Carl Spaatz, who reported directly to Hap Arnold in Washington. General [[Curtis LeMay]] was in operational command. Japanese industrial production plunged as nearly half of the built-up areas of 64 cities were destroyed by [[B-29]] firebombing raids. On March 9-10, 1945 alone, about 100,000 people were killed in a fire storm caused by an attack on Tokyo. | |||

====Mine warfare==== | |||

LeMay oversaw "Operation Starvation" which the interior waterways of Japan were extensively mined by air which seriously disrupted the enemy's logistical operations. | |||

== | ====The atomic bomb==== | ||

In August of 1945 the U.S. attacked two cities with nuclear weapons; on August 6 , [[Hiroshima]] was destroyed with a single weapon, as was [[Nagasaki]] on August 9. More than 200,000 people died as a direct result of these two bombings, but policy makers argued that even more lives were saved because Japan quickly ended the war. Precise figures are not available, but the firebombing together with the nuclear bombing between March and August 1945 may have killed more than one million Japanese civilians. Official estimates from the United States Strategic Bombing Survey put the figures at 330,000 people killed, 476,000 injured, 8.5 million people made homeless and 2.5 million buildings destroyed. | |||

===Soviet entry=== | |||

In February, 1945, Stalin agreed with Roosevelt to enter the Pacific conflict. He promised to act 90 days after the war ended in Europe and did so exactly on schedule on August 9, by launching [[Operation August Storm]]. A battle-hardened, one million-strong Soviet force, transferred from Europe attacked Japanese forces in [[Manchuria]] and quickly defeated their [[Kwantung Army]]. | |||

===Surrender=== | |||

[[Image:Ww2-japan-end.jpg|thumb|right|350px|When the war ended in Aug. 1945, Japan still controlled large areas (in red) in China, as well as many islands that had been leap-frogged.]] | |||

Imperial Japan surrendered on August 15, "V-J Day". The formal surrender was signed on September 2, 1945, on an American battleship in Tokyo Bay. The surrender was accepted by General [[Douglas MacArthur]] as Supreme Allied Commander, with representatives of each Allied nation.. | |||

== | A separate surrender ceremony between Japan and China was held in Nanking on September 9, 1945. | ||

===Occupation=== | |||

In September MacArthur went to Tokyo to oversee the postwar development of the country. This period in Japanese history is known as the occupation. | |||

===Averted invasion=== | |||

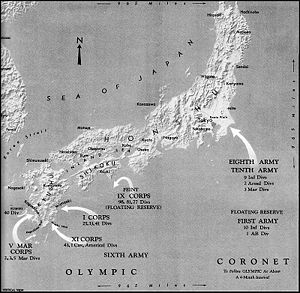

[[Image:Ww2-invade.jpg|thumb|left|300px|The planned invasions of Kyushu (left) and Honshu islands did not happen]] | |||

Under the overall plan [[Operation Downfall]], the Kyushu invasion [[Operation Olympic]] and Honshu invasion [[Operation CORONET]] did not take place. Nine nuclear weapons had been scheduled for use in the Kyushu operations, so it was not a strict alternative to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. | |||

==References== | |||

{{reflist|2}} | |||

Revision as of 13:42, 6 April 2024

World War Two in the Pacific, called the Pacific War in Japan, was the part of World War II that took place in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and in East and South Asia between 1937 and 1945. There is no absolutely accepted starting date, but it is mos commonly accepted as e Japanese invasion of China (Second Sino-Japanese War)) in 1937, but the most decisive actions took place after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the colonies of the U.S., the U.K., and the Netherlands in December 1941.

The war, however, did not magically appear out of context, any more than World War Two in Europe clearly began on 1 September 1939. Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland were clearly precursors, and arguments can be made for proxies such as the Spanish Civil War. The rise of German National Socialism and Italian Fascism were necessary. The European conflict certainly was influenced by World War I and the Versailles Peace Treaty, and not only World War I, but the Russo-Japanese War and First Sino-Japanese War, as well as the Japanese militarism before World War Two, all played a role.

Participants

The major Allied participants were the United States, Britain and is Commonwealth, including Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and India, and the Netherlands played significant roles. China played a major role. Mexico, DeGaulle's Free French Forces, Canada and other countries also took part, especially forces from other British colonies. The Soviet Union fought two short, undeclared border conflicts with Japan in 1938 and 1939, then remained neutral until August 1945, when it joined the Allies and invaded Manchukuo and Korea.

The Axis states which assisted Japan included the Japanese puppet states of Manchukuo and the Wang Jingwei Government]] in China. Thailand joined the Axis powers under duress. Japan enlisted many soldiers from its colonies of Korea and Formosa (now called Taiwan). Some German submarines operated in the Indian Ocean.

Background

Japan had a complex national desire to become a great power, which would require more resources. The initial approach, dating back to the nineteenth century, was exploitation of China,which, while not yet in outright civil war, had a national government under Chiang Kai-shek challenged by regional warlords and revolutionaries. These included Chang Tso-lin in Manchuria, and the growing Chinese Communist movement.

Japan's position at the 1922 Washington Naval Conference was recognized although not to the extent that Japan nationalists would have liked (they saw any situation not at parity with Great Britain and the U.S. as an insult).

Operating without knowledge of the high command but possibly with knowledge of th Palace, officers of the Kwangtung Army staged the September 1931 Manchurian Incident by which it claimed the right to exact military retribution against China and established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Subsequent incidents led the Japanese army to invade parts of Northern China. Japan also occupied for a time Shanghai, and following a protest by the League of Nations, Japan withdrew from the League.

Exploitation of China

By the summer of 1937 Japan had seized Chinese territory to the outskirts of Beijing and began the Second Sino-Japanese War. Japan had established regional dominance over Manchuria and parts of Mongolia, but still saw a need to expand to gain resources. Within government circles in the 1930s, alternative strategies included greater exploitation of China, Strike-North into the Soviet Union and Siberia, and Strike-South into Southeast Asia and Pacific islands.

The Nine-Power Treaty was somewhat as a compromise; signatory nations agreed to abide by the Open Door Policy while the territorial integrity of China was to be respected.

China, French Indochina, and Strike South

Following the German defeat of France in 1940, Japan saw opportunity to further squeeze China. It prevailed on the Vichy French government to allow Japan to occupy and use airbases in Northern French Indochina from which it could bomb China and interdict the flow of western aid to China through French Indochina. The U.S., in response, authorized a loan to China and passed the Export Control Act which authorized the president to restrict the export of strategic materials to nations he deemed threatened national security. Roosevelt used the act to embargo aviation fuel, scrap steel, and other materials to Japan.

Once the Japanese had settled on the Strike-South strategy, they soon realized that they needed at least partial control of French Indochina, both to cut off supplies moving north into China, and to provide air bases in range of targets further south and west. This led to complex relationships with Indochina, reflecting both the creation of Vichy France, and the stronger German control of France through the Tripartite Pact.

In September 1940, Japan entered the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy pledging to aid each other if attacked by another power. Vastly confusing this situation was, however, the April 1941 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact pledging nonaggression between Germany and the Soviet Union. The inherent conflict between the two pacts, if the Strike-North Faction had not already been killed by poor Japanese performance against Soviet troops, made Strike-South the only expansionist strategy left.

Even in Strike-South, Japan preferred to limit its confrontations with the Western colonial powers. At first, it believed it might hold the conflict to Great Britain.

US-Japanese tensions

Negotiations between the United States and Japan proved unproductive. U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull maintained an inflexible position that the first step in any resumption of trade between the U.S. and Japan would be a complete withdrawal of Japanese forces from French Indochina, a step that the militant nationalists controlling Japan were unwilling to take. Their other alternative was to seize the oil fields of the Dutch East Indies, an alternative for which they began war plans. In order to secure their lines of supply between Indonesia and Japan, they would need control of the British base at Singapore and the U.S. colony of the Philippines. Invasion of the Philippines, the Japanese correctly figured, would lead to war with the U.S., and given the strength of the U.S. navy in the Pacific as well as the productive capacity of the United States, the best hope for a Japanese victory in this war would be a decisive victory from which the U.S. would have little other alternatives than to negotiate a peace. To decisively defeat the U.S. fleet, would require a massive blow at a time when the U.S. Navy was least prepared and least expecting a Japanese attack: at the very beginning of the war.

The Pacific at war

In an effort to discourage Japan's war efforts in China, the United States, Britain, and the Dutch government in exile (still in control of the oil-rich Dutch East Indies) stopped selling oil and steel to Japan. This was the "ABCD encirclement" (American-British-Chinese-Dutch) designed to deny Japan of the raw materials needed to continue its war in China. Japan saw this as an act of aggression, as without these resources Japan's military machine would grind to a halt. On December 8, 1941, Japanese forces attacked the British colony of Hong Kong, Shanghai, and the Philippines, which was then a United States possession. Japan also used Vichy French bases in French Indochina to invade Thailand, then used the gained Thai territory to launch an assault against Malaya, a British colony, headed toward the great British naval base at Singapore.

Japanese strategy

Japan had a grand strategy based both on establishing its regional dominance, and also to obtain economic resources it did not believe it could obtain by peaceful means. Within the military-dominated government, there had been a "Strike-South" and a "Strike-North" faction, respectively, seeing the needed resources in Southeast Asia or in Siberia. In either case, it had been conducting large-scale operations in Manchuria and China since 1931.

Especially if Strike-South were taken, which would inevitably impact European allies of the United States, and quite possibly U.S. bases proper, the Japanese military strategy was to force the United States Fleet, after being attrited by peripheral attacks, to steam into the Western Pacific, where it would be vulnerable both to Japanese naval forces and land-based air forces. In support of this strategy, Japan had been building up a system of Pacific island bases since the 1920s.

While Japan joined the Tripartite Pact in 1940, there had already been cooperation with Nazi Germany, and to a lesser extent with Italy. Japan also sought a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union. Prior joining the pact but with known German support, it moved into what was then French Indochina to support its war in China, asking then Vichy France for assistance. These moves were unacceptable within the foreign policy of the United States regarding Southeast Asia, and led to economic embargoes against Japan.

ADM Isoroku Yamamoto, Navy Vice Minister at the time planning intensified, knew the United States and North America well. He counseled against war with the United States, and said, that under the best circumstances, he estimated Japan could maintain a strategic offense for 6-18 months, probably 12, before U.S. industrial mobilization would overwhelm Japanese objectives. His recommendation was for a bold, short-term offensive followed by negotiations, rather than a decisive victory against the United States and other Western powers. Internal Japanese opposition to his views was sufficiently intense that he was transferred to the post of Commander-in-Chief, because be could better be protected against assassination aboard his flagship. Assassination was a very real threat inside Japanese military and government circles in the 1920s and 19302.

It was not clear, to the Japanese, what they would do next after they conquered what they called the Southern Resource Area. Their military forces had always glorified the attack, and had little experience in consolidation, strategic defense, and logistics.

U.S. contingency strategy

The United States strongly supported China. There was little "isolationist" sentiment as American opinion, led by President Franklin D. Roosevelt was strongly hostile to Japan because of its efforts to conquer China.

Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall explained American strategy three weeks before Pearl Harbor:[1]

- "We are preparing for an offensive war against Japan, whereas the Japs believe we are preparing only to defend the Philippines. ...We have 35 Flying Fortresses already there—the largest concentration anywhere in the world. Twenty more will be added next month, and 60 more in January....If war with the Japanese does come, we'll fight mercilessly. Flying fortresses will be dispatched immediately to set the paper cities of Japan on fire. There won't be any hesitation about bombing civilians—it will be all-out."

The main U.S. contingency plan was called RAINBOW 5. U.S. counteroffensive strategy derived from the 1921 paper by Marine Major Earl Ellis.

Initial Japanese attacks

Japan executed its Strike-South plans with movements at Pearl Harbor, the Malay Peninsula and Singapore, and the Philippines.

On December 7, the Japanese carrier-based Mobile Fleet, led by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo under the direction of Commander-in-Chief, Combined Fleet Isoroku Yamamoto, launched a air attack on the American air bases and naval fleet in the attack on Pearl Harbor, sinking or damaging the entire American battleship fleet. U.S. aircraft carriers were not in the harbor, and the attack left submarines and the logistical facilities undamaged.

Although Japan knew that it could not win a sustained and prolonged war against the United States, it was the Japanese hope that, faced with this sudden and massive defeat, the United States would agree to a negotiated settlement that would allow Japan to have free reign in China. This calculated gamble did not pay off; the United States refused to negotiate. Furthermore, the American losses were less serious than initially thought; the American carriers were out at sea while vital base facilities like the fuel oil storage tanks, whose destruction could have crippled the whole Pacific Fleet's operating capacity by itself, were left untouched.

Until the Pearl Harbor, the United States had officially neutral, but in fact was the main supplier of money and munitions to Britain and China, and a major supplier to Soviet Union as wee. The aid went through the Lend-Lease program. Opposition to war in the United States vanished after the attack. On December 11, Nazi Germany declared war on the United States, drawing America into a two-theater war. In 1941, Japan had only a fraction of the manufacturing capacity of the United States, and was therefore perceived as a lesser threat than Germany.

British, Indian and Dutch forces, already drained of personnel and matériel by two years of war with Germany, and heavily committed in the Middle East, North Africa and elsewhere, were unable to provide much more than token resistance to the battle-hardened Japanese. The Allies suffered many disastrous defeats in the first six months of the war. Two major British warships, HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales were sunk by a Japanese air attack off Malaya on December 10, 1941. The government of Thailand surrendered within 24 hours of Japanese invasion and formally allied itself with Japan. Thai military bases were used as a launchpad against Singapore and Malaya. Hong Kong fell on December 25 and U.S. bases on Guam and Wake Island were lost at around the same time.

The Allied governments appointed the British General Sir Archibald Wavell as supreme commander of all "American-British-Dutch-Australian" (ABDA) forces in South East Asia. This gave Wavell nominal control of a huge but thinly-spread force covering an area from Burma to the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines. Other areas, including India, Australia and Hawaii remained under separate local commands.

Japanese strategy and offensives 1942

By early 1942, Japan was unsure what to do next. Their first concern was consolidating their gains in Southeast Asia, which provided adequate resources. They needed, however, more military buffer for their security; Australia was a potential Allied base for counterattacks.[2]

- West into India

- South into Australia

- East towards Midway, Polynesia and Hawaii

1942 began with the Allies in rout, but several major actions showed the turning of the tide. The Battle of the Coral Sea was the first engagement in which a Japanese force turned back from an invasion. The Doolittle Raid made the Japanese believe their eastern perimeter did not extend far enough, and, of a variety of options, selected the invasion of Midway.

Early Japanese attacks

January, 1942 saw the invasions of Burma, the Dutch East Indies, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and the capture of Manila, Kuala Lumpur and Rabaul. After being driven out of Malaya, Allied forces were trapped in the Singapore and, approximately 130,000 surrendered to the Japanese on February 15, 1942[3] Indian, Australian and British troops along with Dutch sailors, became prisoners of war. The pace of conquest was rapid: Bali and Timor also fell in February. The rapid collapse of Allied resistance had left the "ABDA area" split in two.

At the Battle of the Java Sea, in late February and early March, the Japanese Navy inflicted a resounding defeat on the main ABDA naval force, under Admiral Karel Doorman. The Netherlands East Indies campaign subsequently ended with the surrender of Allied forces on Java.

The British, under intense pressure, made a fighting retreat from Rangoon to the Indo-Burmese border. This cut the Burma Road which was the western Allies' supply line to the Chinese National army commanded by Chiang Kai-shek. Cooperation between the Chinese Nationalists and the Communists had waned from its zenith at Battle of Wuhan, and the relationship between the two had gone sour as both attempted to expand their area of operations in occupied territories. Most of the Nationalist guerrilla areas were eventually overtaken by the Communists. On the other hand, some Nationalist units, along with collaborationists, were deployed for blockading the Communists rather than against the Japanese. Further, many of the forces of the Chinese Nationalists were warlords allied to Chiang Kai-shek, but not directly under his command. "Of the 1,200,000 troops under Chiang's control, only 650,000 were directly controlled by his generals, and another 550,000 controlled by warlords who claimed loyalty to his government; the strongest force was the Szechuan army of 320,000 men. The defeat of this army would do much to end Chiang's power."[4] The Japanese used these divisions to press ahead in their offenses.

Filipino and U.S. forces put up a fierce conventional in the Philippines until May 8, 1942; in all than 80,000 men surrendered, but an active resistance movement in the Philippines formed.

Meanwhile, Japanese aircraft had all but eliminated Allied air power in South-East Asia and were making attacks on Darwin in northern Australia, beginning with a disproportionately large and psychologically devastating raid on Darwin, February 19.

Battle of Ceylon

A raid by a powerful Japanese Navy aircraft carrier force into the Indian Ocean resulted in the Battle of Ceylon and sinking of the only British carrier, HMS Hermes in the theater, as well as 2 cruisers and other ships. This effectively drove British naval forces from the Indian ocean and paving the way for Japanese conquest of Burma and a drive towards India.

First Japanese reverse: Coral Sea

By mid-1942, the Japanese Combined Fleet found itself holding a vast area, even though it lacked the aircraft carriers, aircraft, and aircrew to defend it, and the freighters, tankers, and destroyers necessary to sustain it. Moreover, Fleet doctrine was incompetent to execute the proposed "barrier" defense.[5] Instead, they decided on additional attacks in both the south and central Pacific. While Yamamoto had used the element of surprise at Pearl Harbor, Allied codebreakers now turned the tables. They discovered an attack against Port Moresby, New Guinea was imminent.

If Port Moresby fell, it would give Japan control of the seas to the immediate north of Australia. Nimitz rushed the carrier USS Lexington (CV-2), under Admiral Frank Fletcher, to join USS Yorktown (CV-5) and a U.S.-Australian task force, with orders to contest the Japanese advance. The resulting Battle of the Coral Sea was the first naval battle in which ships involved never sighted each other and aircraft were solely used to attack opposing forces.

Reorganization